Beyond the Model: The Hard Truths of Deploying ML in Production

Why Algorithms Are Not Enough: A Guide to the ML Pipeline

This is only the first chapter. To access the complete book, download the full PDF using the button provided at the end of this article.

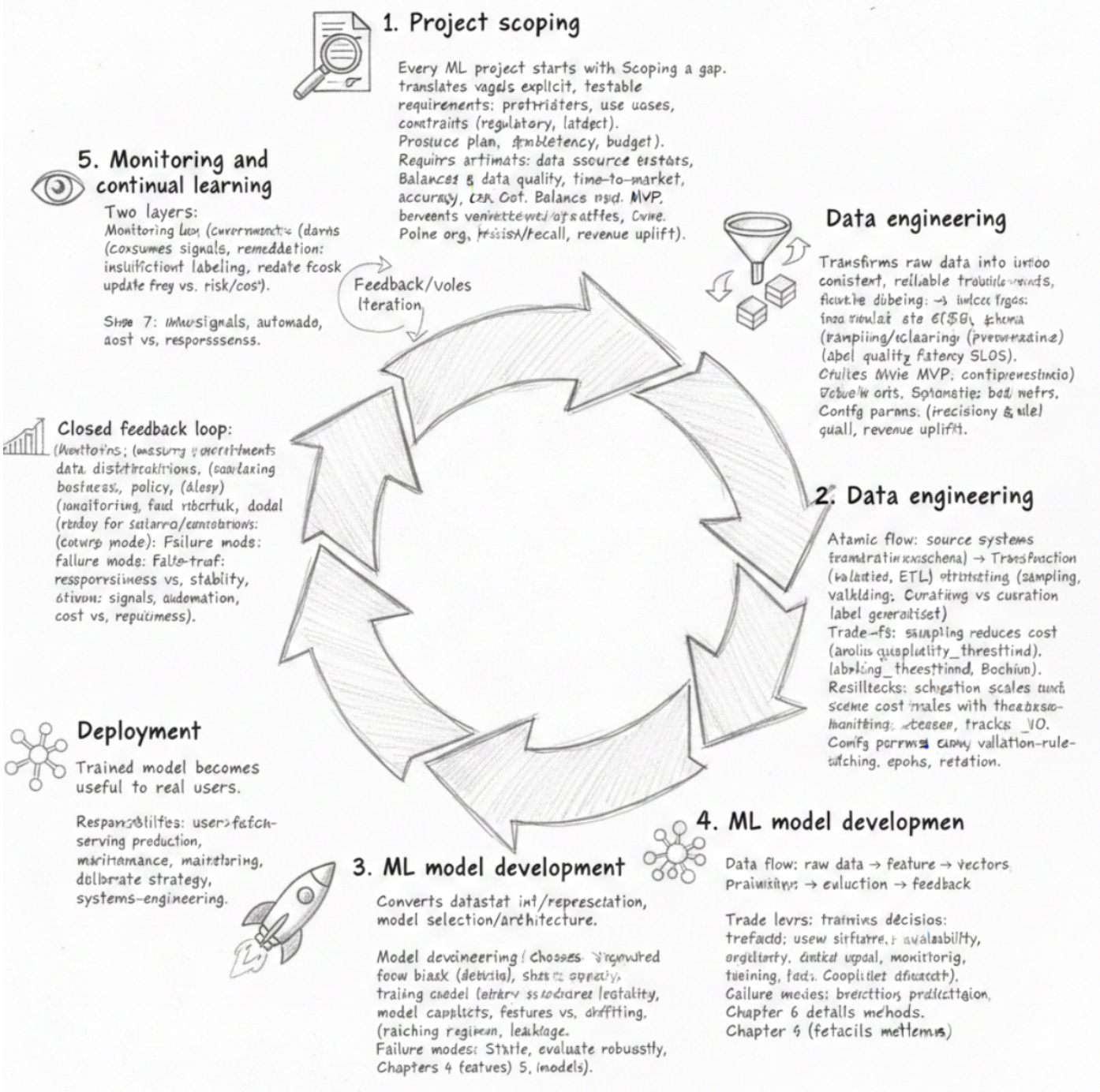

Building a successful ML product begins by recognizing that the model is only one piece of a larger machine. An effective system splits into distinct layers — Interface, Data, ML algorithms, Infrastructure, and Hardware — each with a clear responsibility: Data collects, stores, preprocesses, and labels inputs; ML algorithms handle model selection, training, and inference; Infrastructure implements pipelines, deployment, serving, and operationalization; Hardware supplies compute for both training and inference; and the Interface mediates user interactions and consumes model outputs. This decomposition matters because correctness and performance flow downhill: poor data compromises model quality, inadequate infrastructure limits throughput and latency, and mismatched hardware makes even the best model impractically slow or expensive.

Because ML research continually produces new algorithms, system design must treat the algorithm layer as replaceable rather than central. An algorithm-agnostic design provides stable interfaces and repeatable processes so teams can swap or upgrade models without rearchitecting the whole system. That mindset also shapes the question of whether to use ML at all: the decision boundary — when and when not to use machine learning — is a cost‑benefit judgment based on problem suitability, data availability, operational complexity, and deployment constraints. When ML is appropriate, the emphasis shifts from prescribing a single technique to following a model selection process that reliably evaluates options in the context of system constraints (see Chapter 5). In practice that means measuring not only research metrics but also production considerations such as latency during serving, memory and compute footprints on target Hardware, and how easy it is to deploy and version a candidate.

At production scale, two realities drive architecture and operations. First, ML systems typically consume massive amounts of data and need heavy computational power, which creates bottlenecks in storage capacity, network I/O, training throughput, and inference latency; these constraints force trade-offs in data retention, batching, and model complexity. Second, production ML requires engineering practices that go beyond research: monitoring, validation, maintainability, rollback procedures, and automated retraining become essential to handle data quality issues, model drift, and hardware limits. This engineering posture also responds to non‑technical stakes — unaddressed deployment issues can cause serious societal harm or business failure — so safety, fairness, and compliance must be treated as first‑class system requirements. Teams frequently face a time‑to‑market vs. robustness trade‑off: shipping fast can expose users and business to risk, while delaying until every operational edge case is covered increases time and cost. As a result, practical ML systems are iteratively engineered to be deployable, reliable, scalable, and adaptable, with continuous loops for monitoring, retraining, versioning, and rollback to manage implicit failure modes and maintain long‑term correctness.

When to Use Machine Learning

Machine learning is a tool, not a silver bullet — the first question for any project is whether its benefits outweigh the costs. Ask explicitly is ML necessary or cost-effective? before proceeding: ML can deliver value when hand-coded rules fail, but it also introduces development, data, and maintenance overhead that must factor into your return‑on‑investment calculation. Framing ML correctly helps you make that judgment. At its core, Machine Learning (ML) can be decomposed into six meaningful pieces — learn, complex, patterns, existing data, predictions, and unseen data — and each term imposes an operational requirement on how you approach the problem.

Start with what “learn” and “complex” imply: learn means using inductive approaches that derive behavior from examples rather than explicit rules, so you must supply representative examples instead of coding logic by hand and expect model behavior to emerge from training. Complex signals that the relationships you care about are hard to enumerate — they may be nonlinear, high‑dimensional, or combinatorial — and therefore impractical to capture with deterministic code or simple heuristics. “Patterns” refers to statistical regularities rather than immutable laws, so what the model exploits are correlations that can be useful but also spurious; as a result you must validate findings and test for robustness. Taken together, these ideas explain why ML is chosen for problems where domain logic is messy or too large to express as rules, and why emergent behavior and careful validation are part of the price you pay.

The remaining terms tie ML to data and decisioning. Existing data is a gating constraint: effective ML demands sufficient volume, accurate labels, coverage of relevant cases, and representativeness of future inputs. Predictions reminds us that model outputs are typically probabilistic and approximate, so you need clear metrics, calibration, and an analysis of how much downstream error your system can tolerate. Finally, unseen data makes generalization the central engineering objective and risk: you must plan for dataset bias, distribution shift, and out‑of‑distribution cases, and implement monitoring and robustness checks in production. These requirements drive concrete operational costs — data collection and labeling, training compute, model validation, ongoing drift monitoring, and retraining — and they explain the trade‑off: prefer non‑ML solutions when rules or algorithms are simpler, cheaper, more predictable, or when data is scarce, because ML buys flexibility and pattern discovery at the cost of explainability, repeatability, and higher maintenance overhead.

In practice, use ML when four conditions hold together: the problem is driven by complex patterns that are impractical to hand‑code, you have adequate and representative historical data, you can define measurable labels or objectives for evaluation, and the system can tolerate approximate, probabilistic predictions. If one of these elements is missing — for example, insufficient data or a requirement for deterministic, fully explainable decisions — a rule‑based approach will often be the better, cheaper choice. Ultimately, adopting ML is a strategic decision: it can unlock solutions that hand‑written logic cannot capture, but it requires accepting emergent behavior, investing in data and operational processes, and planning for ongoing validation and maintenance.

Relational systems and machine learning solve different classes of problems, and understanding that distinction explains why ML matters. A relational database is deterministic and rule-based: you declare an explicit schema and relationships, and the system returns results that follow those rules. Machine learning, by contrast, provides an inductive mechanism that infers patterns from examples rather than being told exact relationships. To do that you must give the learner a training signal — typically a dataset of inputs paired with desired outputs — so the system can approximate a mapping f: X → Y. In the common supervised learning pattern you supply many (input, output) pairs; during training the model adjusts parameters to minimize a loss between its predictions and the true labels, producing a predictor that generalizes to unseen inputs. For example, in an Airbnb price-prediction model the inputs (features) might include square footage, room count, neighborhood, amenities, and rating, while the label is the rental price; by engineering useful features and choosing the right label, the model learns to estimate price for new listings.

Putting learning into production requires clearly defined components and a left-to-right data flow during training that collapses into a single step at inference time. First you perform data collection and labeling to create the training set; next you perform feature representation/engineering to map raw attributes into the model’s inputs. The learning algorithm/model acts as a function approximator and is trained inside a training loop that uses a loss, an optimizer, and validation to guide parameter updates. Once trained, inference serving applies only the trained model to new inputs. This separation explains performance characteristics and costs: training is typically compute- and time-intensive — often requiring batch or iterative optimization and distributed compute to scale — whereas inference is usually optimized for low latency and high throughput through model size choices, hardware acceleration, and batching.

Designing an effective ML system is an exercise in managing trade-offs around capacity, data, and robustness. Model capacity determines how complex a relationship the model can represent: too much capacity risks overfitting to training data, while too little leads to underfitting; inductive bias (architecture and regularization choices) guides generalization when data is limited. The system’s ability to learn also depends on sample complexity — the volume, diversity, and label fidelity of training data — because insufficient, biased, or noisy labels produce systematic errors. Common failure modes include overfitting, underfitting, label noise, and covariate shift (distribution drift that degrades runtime performance). As a result you need validation and testing, regularization, monitoring for drift, retraining pipelines, and robust feature selection to build resilience. Finally, practical design knobs — feature choices, label definition, model architecture, loss function, regularization, and hyperparameters — directly influence generalization, latency, and robustness; in many cases collecting better labeled data or changing model bias yields bigger gains than micro-optimizing algorithms. The key takeaway is that learning systems are built around data plus inductive machinery: get the training signal and representation right, and you enable generalization; ignore data quality or capacity trade-offs, and the system will reliably expose its failure modes.

Complex: the patterns are complex

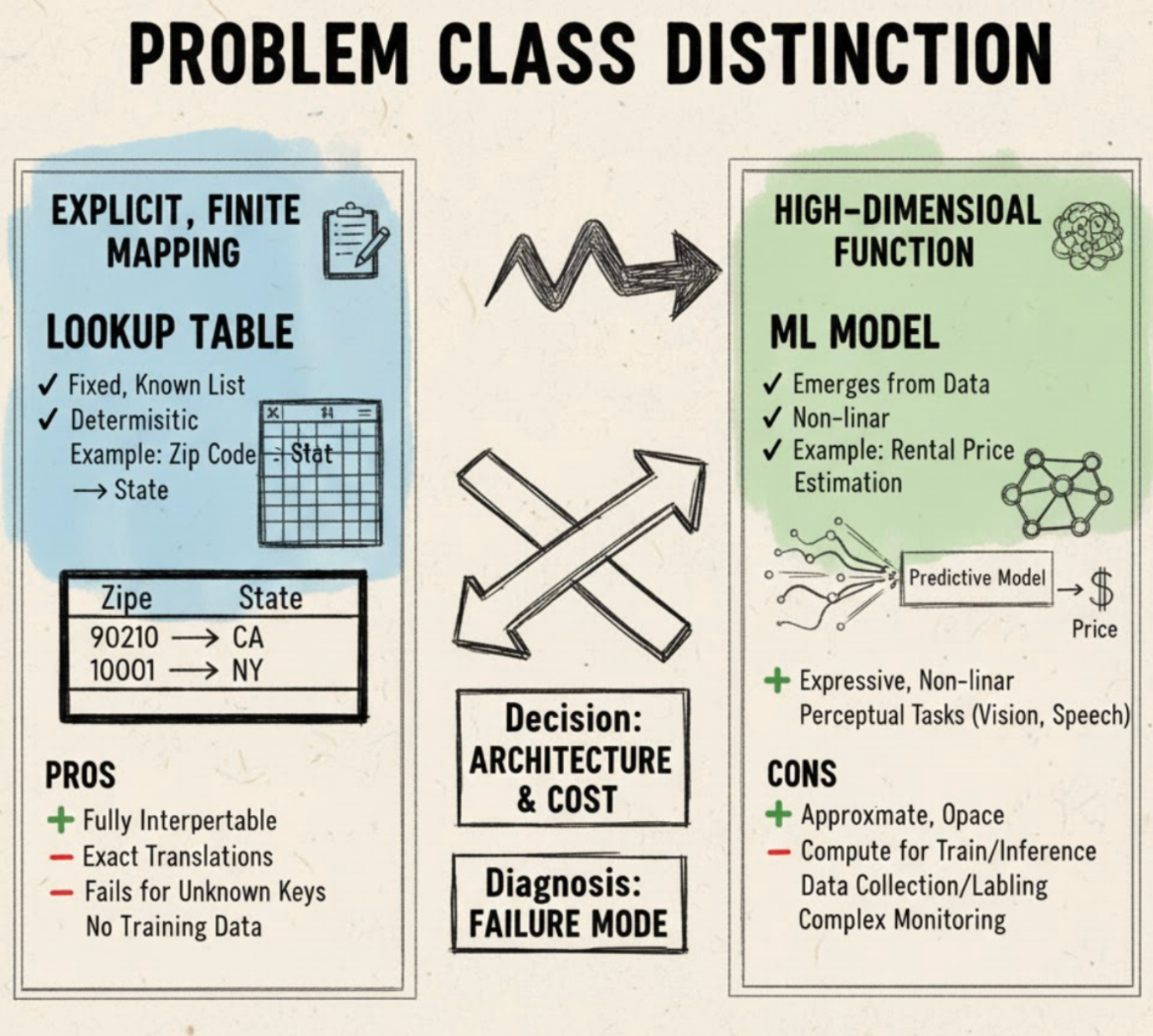

When you design a component that maps inputs to outputs, the first and most important decision is a problem class distinction: is the behavior expressible as an explicit, finite mapping or is it better modeled as a high‑dimensional, implicitly defined function? This matters because the answer determines everything that follows — from the architecture and operational cost to how you diagnose failures. A canonical explicit example is zip code → state, where a fixed, known list of key→value pairs exactly defines the behavior. In contrast, estimating a rental price from many listing characteristics is a high‑dimensional problem: the relationship emerges from data, is nonlinear, and is impractical to enumerate by hand.

Building a successful ML product begins by recognizing that the model is only one piece of a larger machine. An effective system splits into distinct layers — Interface, Data, ML algorithms, Infrastructure, and Hardware — each with a clear responsibility: Data collects, stores, preprocesses, and labels inputs; ML algorithms handle model selection, training, and inference; Infrastructure implements pipelines, deployment, serving, and operationalization; Hardware supplies compute for both training and inference; and the Interface mediates user interactions and consumes model outputs. This decomposition matters because correctness and performance flow downhill: poor data compromises model quality, inadequate infrastructure limits throughput and latency, and mismatched hardware makes even the best model impractically slow or expensive.

Because ML research continually produces new algorithms, system design must treat the algorithm layer as replaceable rather than central. An algorithm-agnostic design provides stable interfaces and repeatable processes so teams can swap or upgrade models without rearchitecting the whole system. That mindset also shapes the question of whether to use ML at all: the decision boundary — when and when not to use machine learning — is a cost‑benefit judgment based on problem suitability, data availability, operational complexity, and deployment constraints. When ML is appropriate, the emphasis shifts from prescribing a single technique to following a model selection process that reliably evaluates options in the context of system constraints (see Chapter 5). In practice that means measuring not only research metrics but also production considerations such as latency during serving, memory and compute footprints on target Hardware, and how easy it is to deploy and version a candidate.

At production scale, two realities drive architecture and operations. First, ML systems typically consume massive amounts of data and need heavy computational power, which creates bottlenecks in storage capacity, network I/O, training throughput, and inference latency; these constraints force trade-offs in data retention, batching, and model complexity. Second, production ML requires engineering practices that go beyond research: monitoring, validation, maintainability, rollback procedures, and automated retraining become essential to handle data quality issues, model drift, and hardware limits. This engineering posture also responds to non‑technical stakes — unaddressed deployment issues can cause serious societal harm or business failure — so safety, fairness, and compliance must be treated as first‑class system requirements. Teams frequently face a time‑to‑market vs. robustness trade‑off: shipping fast can expose users and business to risk, while delaying until every operational edge case is covered increases time and cost. As a result, practical ML systems are iteratively engineered to be deployable, reliable, scalable, and adaptable, with continuous loops for monitoring, retraining, versioning, and rollback to manage implicit failure modes and maintain long‑term correctness.

When to Use Machine Learning

Machine learning is a tool, not a silver bullet — the first question for any project is whether its benefits outweigh the costs. Ask explicitly is ML necessary or cost-effective? before proceeding: ML can deliver value when hand-coded rules fail, but it also introduces development, data, and maintenance overhead that must factor into your return‑on‑investment calculation. Framing ML correctly helps you make that judgment. At its core, Machine Learning (ML) can be decomposed into six meaningful pieces — learn, complex, patterns, existing data, predictions, and unseen data — and each term imposes an operational requirement on how you approach the problem.

Start with what “learn” and “complex” imply: learn means using inductive approaches that derive behavior from examples rather than explicit rules, so you must supply representative examples instead of coding logic by hand and expect model behavior to emerge from training. Complex signals that the relationships you care about are hard to enumerate — they may be nonlinear, high‑dimensional, or combinatorial — and therefore impractical to capture with deterministic code or simple heuristics. “Patterns” refers to statistical regularities rather than immutable laws, so what the model exploits are correlations that can be useful but also spurious; as a result you must validate findings and test for robustness. Taken together, these ideas explain why ML is chosen for problems where domain logic is messy or too large to express as rules, and why emergent behavior and careful validation are part of the price you pay.

The remaining terms tie ML to data and decisioning. Existing data is a gating constraint: effective ML demands sufficient volume, accurate labels, coverage of relevant cases, and representativeness of future inputs. Predictions reminds us that model outputs are typically probabilistic and approximate, so you need clear metrics, calibration, and an analysis of how much downstream error your system can tolerate. Finally, unseen data makes generalization the central engineering objective and risk: you must plan for dataset bias, distribution shift, and out‑of‑distribution cases, and implement monitoring and robustness checks in production. These requirements drive concrete operational costs — data collection and labeling, training compute, model validation, ongoing drift monitoring, and retraining — and they explain the trade‑off: prefer non‑ML solutions when rules or algorithms are simpler, cheaper, more predictable, or when data is scarce, because ML buys flexibility and pattern discovery at the cost of explainability, repeatability, and higher maintenance overhead.

In practice, use ML when four conditions hold together: the problem is driven by complex patterns that are impractical to hand‑code, you have adequate and representative historical data, you can define measurable labels or objectives for evaluation, and the system can tolerate approximate, probabilistic predictions. If one of these elements is missing — for example, insufficient data or a requirement for deterministic, fully explainable decisions — a rule‑based approach will often be the better, cheaper choice. Ultimately, adopting ML is a strategic decision: it can unlock solutions that hand‑written logic cannot capture, but it requires accepting emergent behavior, investing in data and operational processes, and planning for ongoing validation and maintenance.

Relational systems and machine learning solve different classes of problems, and understanding that distinction explains why ML matters. A relational database is deterministic and rule-based: you declare an explicit schema and relationships, and the system returns results that follow those rules. Machine learning, by contrast, provides an inductive mechanism that infers patterns from examples rather than being told exact relationships. To do that you must give the learner a training signal — typically a dataset of inputs paired with desired outputs — so the system can approximate a mapping f: X → Y. In the common supervised learning pattern you supply many (input, output) pairs; during training the model adjusts parameters to minimize a loss between its predictions and the true labels, producing a predictor that generalizes to unseen inputs. For example, in an Airbnb price-prediction model the inputs (features) might include square footage, room count, neighborhood, amenities, and rating, while the label is the rental price; by engineering useful features and choosing the right label, the model learns to estimate price for new listings.

Putting learning into production requires clearly defined components and a left-to-right data flow during training that collapses into a single step at inference time. First you perform data collection and labeling to create the training set; next you perform feature representation/engineering to map raw attributes into the model’s inputs. The learning algorithm/model acts as a function approximator and is trained inside a training loop that uses a loss, an optimizer, and validation to guide parameter updates. Once trained, inference serving applies only the trained model to new inputs. This separation explains performance characteristics and costs: training is typically compute- and time-intensive — often requiring batch or iterative optimization and distributed compute to scale — whereas inference is usually optimized for low latency and high throughput through model size choices, hardware acceleration, and batching.

Designing an effective ML system is an exercise in managing trade-offs around capacity, data, and robustness. Model capacity determines how complex a relationship the model can represent: too much capacity risks overfitting to training data, while too little leads to underfitting; inductive bias (architecture and regularization choices) guides generalization when data is limited. The system’s ability to learn also depends on sample complexity — the volume, diversity, and label fidelity of training data — because insufficient, biased, or noisy labels produce systematic errors. Common failure modes include overfitting, underfitting, label noise, and covariate shift (distribution drift that degrades runtime performance). As a result you need validation and testing, regularization, monitoring for drift, retraining pipelines, and robust feature selection to build resilience. Finally, practical design knobs — feature choices, label definition, model architecture, loss function, regularization, and hyperparameters — directly influence generalization, latency, and robustness; in many cases collecting better labeled data or changing model bias yields bigger gains than micro-optimizing algorithms. The key takeaway is that learning systems are built around data plus inductive machinery: get the training signal and representation right, and you enable generalization; ignore data quality or capacity trade-offs, and the system will reliably expose its failure modes.

Complex: the patterns are complex

When you design a component that maps inputs to outputs, the first and most important decision is a problem class distinction: is the behavior expressible as an explicit, finite mapping or is it better modeled as a high‑dimensional, implicitly defined function? This matters because the answer determines everything that follows — from the architecture and operational cost to how you diagnose failures. A canonical explicit example is zip code → state, where a fixed, known list of key→value pairs exactly defines the behavior. In contrast, estimating a rental price from many listing characteristics is a high‑dimensional problem: the relationship emerges from data, is nonlinear, and is impractical to enumerate by hand.

For the explicit case you use lookup tables: store a canonical mapping, retrieve the value deterministically for a given key, and maintain the table entries as the single source of truth. Implementation responsibilities are straightforward — reliable storage, fast retrieval (constant time), and operational processes to update or correct entries — and they require no labeled examples or model training. As a result you get fully interpretable, exact translations with very low latency. The obvious limitation is coverage: a lookup simply fails or returns unknown for keys not present in the table, and its expressiveness is bounded by the encoded keys. Prefer this approach when the mapping is explicit, finite, and stable.

When the mapping is complex or emergent, you use ML models and a data‑driven learning pattern: collect features and target labels, train a model to approximate the underlying mapping, and serve it for inference. Component responsibilities expand to include data collection and labeling, model training, deployment/serving infrastructure, and lifecycle activities such as retraining and versioning. This pipeline translates observed examples into learned parameters that produce predictions. The trade‑offs are clear: ML is expressive and can capture nonlinear, high‑dimensional patterns (which is why it succeeds on perceptual tasks like object detection and speech recognition), but models are approximate, often opaque, and require compute for both training and inference. Performance and latency depend on model complexity and serving infrastructure, and engineering cost rises because you must provision compute, collect labeled data, and continuously monitor model behavior.

These two patterns also differ in how you diagnose errors and in the decision rules you apply. A lookup error points you at table coverage or stale data — you fix the table. A model error points you at dataset bias, insufficient examples, or model capacity — you analyze data and training. Operationally, that means different monitoring, alerting, and maintenance practices. In practice, choose the simplest component that satisfies your requirements: use rule/table‑based components for exact, finite mappings; invest in ML when the mapping is high‑dimensional, hard to formalize, or clearly emergent from data. The consequence of this choice shapes interpretability, latency, engineering effort, and the types of failure modes you must prepare to handle.

Patterns: there are patterns to learn

Machine learning only pays off when real, learnable patterns exist in the data. If the process you’re trying to model is effectively random — think of repeated outcomes from a fair die — there is no predictable signal for an ML algorithm to extract, so investing in models is wasteful. In practice, however, the existence of a pattern is often non-obvious and conditional: a relationship like “Elon Musk tweets → Bitcoin price moves” may be real, but it becomes detectable only after you collect the right observations, design informative features, choose a model with sufficient capacity, and apply rigorous training and evaluation. Because of this conditionality, a trained model’s inability to predict a target does not prove there is no underlying pattern; negative results can equally reflect limited dataset size, poor feature representation, an inappropriate model class, label noise, or sloppy evaluation.

A more practical hinge of whether ML is possible is data availability: supervised learning requires relevant input–output pairs at adequate scale and coverage. For example, predicting tax liabilities is theoretically possible only if you can access population-scale tax and income records — without that data, the problem is blocked irrespective of any underlying signal. Relatedly, techniques that look like they need “no data” have hidden dependencies: zero-shot (aka zero-data) performance on a new task succeeds not because the model learned from nothing, but because it was pre-trained on broad or related datasets and can transfer that prior knowledge. In contrast, online learning lets you deploy a model without task-specific pre-training by learning from production data over time; this removes the pre-training requirement at launch but trades it for poor initial performance and a risk of degraded customer experience while the model accumulates data. A common pragmatic middle ground is the human-in-the-loop bootstrap — “fake-it-til-you-make-it” — where humans provide initial predictions to generate labeled examples for later automated training; this accelerates getting a working service but slows scale-up, can introduce human label biases, and delays the payoff of full automation.

Because each cold-start option has different costs and failure modes, the choice among zero-shot, online learning, and human-in-the-loop depends on data availability, time-to-market, acceptable initial accuracy, and risk tolerance for user-facing errors — there is no universally optimal path. You must also address operational risk: putting insufficiently trained models into production causes immediate user-facing failures, loss of trust, and business harm. Mitigations include robust monitoring, fallbacks to human responders or rule-based logic, and staged rollouts that limit exposure while you validate performance. Finally, detecting whether a genuine pattern exists requires rigorous empirical practice: sound training/test splits, statistical-significance checks, and iterative experiments that isolate data, feature, and model factors. Data-collection constraints—privacy, legal access, or labeling cost—directly shape which patterns are feasible to learn; if you cannot acquire the necessary inputs (for example, private tax records), no amount of modeling will recover the signal. In short: verify pattern plausibility, confirm data availability, pick a cold-start strategy that matches your tolerance for initial errors, and instrument strong evaluation and operational guardrails before betting on ML.

Predictions: it’s a predictive problem

Machine learning works by estimating values rather than computing exact proofs: treat each task as “estimate the value of X” — whether X is a future outcome, a current hidden state, or the result of an expensive subroutine. This perspective matters because many engineering problems today are dominated by compute‑intensive subroutines (simulations, ray tracers, numerical solvers) that are costly to run repeatedly. By reframing such tasks as prediction problems you can train a model to act as a predictive estimator that approximates the expensive computation, turning a deterministic computation into a learned surrogate that produces answers far more cheaply at inference time.

That reframing yields a surrogate/emulator architecture: you replace an expensive exact computation with an ML model that maps inputs to approximate outputs. The economic benefit is amortized cost — you pay a large upfront training bill, but then enjoy many cheap, low‑latency inferences. As a result, systems that require many repeated queries see dramatic throughput gains per unit of compute, at the cost of accepting approximation error. A concrete example is graphics and rendering: models can approximate pixel‑level operations (image denoising, screen‑space shading) to deliver perceptually similar images with far less compute than running the full pipeline for every frame. Whether you choose this path depends on the core trade‑off of accuracy vs. compute/time: ML reduces latency and cost but introduces approximation error; acceptability hinges on the domain’s error tolerance and the downstream impact of mistakes.

Making a surrogate work in practice depends heavily on data and engineering choices. Surrogates require ground truth from the exact computation or labeled examples, so model generalization is bounded by the coverage and representativeness of the training set. Per‑query performance is constrained by inference latency, model size, and memory bandwidth, so the largest wins arise when the original exact computation dominates overall cost. Key configuration levers — model capacity and architecture, training dataset size and diversity, the loss/objective (L2 versus perceptual losses), and deployment latency/throughput targets — directly shape accuracy, speed, and robustness. You can scale by parallelizing inference and applying model quantization and serving optimizations, but you remain limited by inference compute, memory, and the model’s tendency to degrade under distributional shift; this creates operational needs for retraining and continual learning.

Those limitations produce important failure modes and system implications you must address. Surrogates can introduce systematic approximation bias, suffer catastrophic errors on out‑of‑distribution inputs, and have unbounded worst‑case deviations from the exact solution. This leads to a design pattern for resiliency: build hybrid pipelines that pair ML predictions with cheap validation checks or conditional fallbacks to the exact computation so critical or ambiguous cases are contained. Practically, adopting predictive approximations raises operational complexity — you need dataset generation pipelines, model evaluation metrics that include worst‑case analyses, monitoring and uncertainty estimation, and processes for incremental retraining and rollbacks. In short, use ML approximations when the cost of exact computation far exceeds acceptable approximation error and you have sufficient labeled data; otherwise prefer deterministic algorithms when correctness is required.

Unseen data: Unseen data shares patterns with the training data

Machine learning models work by extracting statistical regularities from historical data and using those regularities to make predictions about new cases. This becomes a problem whenever the new, unseen data does not share those same regularities — for example, training a model on app-download patterns from 2008 when the market was dominated by Koi Pond and then expecting it to predict downloads in 2020 is likely to fail because the underlying landscape has changed. Formally, the core requirement is that the training distribution and the distribution that generates unseen (test or production) data should be similar; saying two datasets are drawn from “similar probability distributions” is the precise way to express the alignment you need for learned patterns to remain useful.

A fundamental difficulty arises because the true distribution of future data is unknown a priori, so you can never be certain that the relationships your model learns will persist in deployment. To bridge that gap practitioners commonly make an explicit modeling assumption of temporal stability (users’ behaviors tomorrow ≈ users’ behaviors today). This assumption simplifies model design: if you accept it, you can train once on recent historical data and deploy standard ML pipelines that exploit recurring patterns. As a result you often get fast, low-cost wins in engineering time and immediate model performance, but you also increase fragility — if the world shifts, those same models can degrade quickly.

That fragility is the concrete failure mode known as distributional shift or temporal shift: when the data-generating process changes (different popular apps, new user behaviors), the statistical features the model relied on become irrelevant and performance drops. Because most ML algorithms today learn by exploiting recurring regularities, they excel on stable problems but perform poorly when those regularities disappear. To reduce this risk, your training data should be recent and representative of expected production conditions; stale historical examples bias models toward obsolete patterns. Equally important, practical systems must include detection and feedback: monitoring production performance, triggering investigation when metrics fall, and scheduling retraining or other corrective actions — in short, you cannot rely on “we’ll find out soon enough” without instrumentation that tells you when the assumption has broken.

Designing around this reality forces a trade-off. You can choose to accept stationarity and deploy quickly with standard tooling, or you can invest up front in robustness — continuous data ingestion, heavier monitoring, and techniques like continual learning or domain adaptation — to handle inevitable shifts. Each path has different engineering and maintenance costs. The pragmatic guidance is clear: prioritize ML when your problem exhibits stable, recurring patterns; otherwise explicitly plan for assumption validation, continuous data collection, monitoring, and model update cycles so your system can detect and respond when unseen data stops sharing the patterns your model learned.

It’s repetitive

Machine learning systems often struggle where humans do not: humans can generalize from a handful of examples — a capability known as few-shot learning — while many algorithms still demand large labeled datasets. This matters because some real-world tasks contain a lot of repetition: the same visual motif, text pattern, or behavior appears many times. When the training distribution contains repeated instances of the same pattern, the problem of learning becomes qualitatively easier because the model sees the same signal many times rather than needing to infer it from a single or a handful of distinct examples.

The reason repetition helps is statistical. Repetition increases the frequency of a pattern in the training data, which strengthens the empirical signal used to estimate parameters or feature correlations. Put another way, sample complexity — the number of labeled examples a model needs to reach a target error — falls as pattern frequency rises. Because empirical estimates (for example, gradient updates or correlation estimates) converge faster with more observations of the same structure, models hit acceptable performance with fewer distinct concepts to learn. This leads to a practical rule: effective data requirement is inversely correlated with repetitiveness — more repetition → fewer labeled examples needed to reach a given performance.

This insight also clarifies trade-offs in system design. Humans achieve few-shot behavior through strong inductive biases (built-in assumptions about how the world works); most standard ML models lack comparable priors and therefore compensate by collecting more data. As a result, when you know a task is repetitive you can shift strategy: favor simpler models, smaller datasets, or architectures that explicitly exploit repeated structure rather than trying to bridge the gap by brute-force scaling. Concretely, this means prioritizing methods that leverage repetition such as pattern detectors, shared feature extractors, and transfer across repeated instances. In contrast, highly diverse or non-repetitive tasks strip away the repetition advantage and force systems back into high-data regimes or require stronger inductive biases to maintain performance.

Practically, you can monitor pattern frequency (the occurrence count per class or pattern) as an actionable metric: it predicts where labeling or modeling effort will pay off. If pattern frequency is high, invest in lightweight models and shared representations; if it is low, expect higher sample complexity and consider collecting more diverse labeled data or introducing task-specific priors. In short, repetition is a lever you can pull to reduce sample complexity — recognizing and exploiting it guides both architectural choices and where to invest labeling resources.

The cost of wrong predictions is cheap

Machine learning models are not perfect; unless a model achieves 100% accuracy all the time, mistakes are inevitable, and that inevitability must shape how you design the system around the model. This reality means you should treat ML as a tool whose suitability depends less on raw accuracy numbers and more on the consequences of being wrong. When a single incorrect prediction has small negative effect, you can tolerate frequent mistakes operationally and gain value from rapid iteration and automated decision-making. For example, recommender systems are a canonical case: a bad recommendation usually costs nothing more than a skipped suggestion, so teams can deploy aggressively, iterate quickly, and accept a higher error rate without causing major harm.

Choosing where to apply ML is fundamentally a cost-sensitivity decision: compare the expected cost of incorrect predictions against the value produced by correct ones. In low-cost domains, the expected benefit of many correct predictions outweighs the nuisance of some wrong ones; ML is a natural fit. In high-cost-error domains — take self-driving cars as an example — a single mistake can be catastrophic, so ML is only acceptable if, at the population level, the aggregate benefits of correct predictions outweigh the rare but severe harms. This leads to applying an expected-value or risk-vs-benefit assessment at scale rather than demanding per-instance perfection. Relatedly, the “statistically safer than humans” criterion evaluates whether the model reduces net harm across many decisions, not whether it ever makes an isolated mistake.

Those cost considerations drive architecture and operational practice. When error costs are low, you can build simpler, more automated pipelines and tolerate exploration: feature changes, model swaps, and A/B tests flow through with limited additional safety checks. In contrast, high-error-cost applications require conservative architectures, rigorous validation, and extra safety and mitigation layers (for example, fallback logic, human-in-the-loop checks, or conservative thresholds). There is a trade-off here: tolerating imperfect accuracy reduces upfront engineering effort and speeds iteration, but it shifts burden downstream to tolerance mechanisms such as user forgiveness, retry logic, or business rules. Trying to drive error rates down materially increases development complexity, validation effort, and operational cost.

Finally, when single failures can be catastrophic, you must explicitly quantify your tolerance for rare severe failures and let that number drive critical design choices — including whether to use ML at all. The decision to apply ML is therefore not a function of achievable accuracy alone; it depends on how errors translate into business or user costs and whether correct predictions deliver enough value to justify the residual risk. In short, pick ML where wrong predictions are cheap, design conservatively where they are not, and measure success by net reduction in harm and expected value, not by the absence of any mistakes.

It’s at scale

When we say “at scale” in production ML, we usually mean very high sustained prediction volume — not a single rare inference but millions of predictions per time period (for example, millions of emails per year or thousands of support tickets per day). This reality forces you to treat inference as a continuous, cost-sensitive pipeline: a model must deliver predictions continuously, efficiently, and often with fresh data. A seemingly singular decision can become many inferences over time because models are frequently re-evaluated as new evidence arrives (for example, an election forecast updated hourly). That temporal multiplexing pushes designs toward streaming/online inference and stateful workflows rather than occasional one-off batch jobs.

Choosing how to serve predictions at scale centers on a few core trade-offs. On one axis you have online low-latency serving — per-request inference that yields fresh features and low response times — and on the other you have batch/precomputed inference, which sacrifices freshness for higher throughput and lower per-prediction cost. This decision ties directly into operational metrics you must optimize: throughput (predictions/sec), per-prediction latency (ms–s), and cost-per-prediction. Practical scaling strategies include horizontal autoscaling of stateless inferencers, batching requests (batch_size) to improve CPU/GPU utilization, and precomputing predictions where acceptable. At the same time, feature freshness and ingestion become first-class concerns: a robust feature store and streaming pipelines, with well-defined feature_TTL and consistency semantics (stale vs fresh), directly influence accuracy, latency, and system complexity. To make the initial ML investment pay off, you also amortize costs by reusing models/services, using shared feature stores, and adopting multi-tenant serving.

Operating at scale amplifies both costs and failure modes, so architecture and processes must anticipate them. High-frequency predictions increase expenses across data, compute, infrastructure, and talent, so you tune design knobs like prediction_cadence, model_refresh_interval, caching TTLs, and autoscale_threshold to balance latency, accuracy, and cost. Failure patterns that are harmless at small scale become critical: input bursts can create backpressure, feature-store unavailability can block online inference, serving resources can be exhausted, and unbounded prediction frequency can explode costs. Resilience tactics include rate limiting, circuit breakers, backpressure-aware queues, and degraded-mode fallback logic. Scale also creates operational opportunities: abundant production data enables continuous monitoring for prediction drift, latency and error-rate SLOs, capacity planning, and automated retraining triggers. Finally, having “a lot of data” reduces sampling variance and supports more complex models, but it also increases storage, labeling, and pipeline throughput requirements; systems must therefore support efficient data versioning, labeling workflows, and high-throughput training pipelines to fully leverage scale.

Key takeaway: at-scale systems treat prediction as an ongoing, resource-governed service where freshness, throughput, latency, cost, and resilience are tightly coupled. Your architecture, operational practices, and configuration knobs must explicitly balance those trade-offs to turn high-volume inference into reliable, cost-effective value.

The patterns are constantly changing

When the world your system observes keeps shifting, static detection logic breaks down. A heuristic that once caught spam (think “Nigerian prince” patterns) becomes brittle as attackers change motifs, and maintaining hand-tuned rules requires expensive, continual re-analysis of how the world changed. This is the core problem of concept drift: the data distribution that drove your original decisions moves, and deterministic, human-maintained rules that were once precise begin to silently degrade — missing new cases or producing more false positives. In contrast, ML models learn behavior from examples and are naturally better suited to environments where patterns shift frequently or are difficult to express in declarative logic.

To make ML practical in this setting you must design a system that treats adaptation as part of the architecture. Rather than re-engineering rules for every new pattern, you supply new labeled data and either retrain or fine-tune models. This leads to building pipelines that ingest fresh examples, capture ground-truth labels or human-review signals, retrain on a cadence (periodic or trigger-based), validate, and redeploy — shifting maintenance effort from rule-writing to data collection, labeling, training infrastructure, and deployment management. When an end-to-end ML solution is impractical or risky, apply a decomposition pattern: partition the problem and use ML only where it fits — for example, classify queries as matching an FAQ for automatic answers while routing uncertain or high-risk queries to human support. As a result you gain partial automation and contain failure blast radius. To keep the system resilient, monitor model performance and distribution statistics, maintain fallback rule-based behavior for critical cases, and enable human-in-the-loop correction for edge cases.

These choices carry trade-offs and operational consequences. Rules can be cheap and precise for stable, well-known cases, but incur high ongoing maintenance when patterns change. ML reduces logic maintenance but increases costs for labeling, compute for training, model validation, and monitoring. Timing matters: adopting ML early can yield faster adaptation and competitive advantage, but immature ML solutions may be less cost-effective at first; waiting for maturity risks falling behind. Practical controls include setting a retraining cadence that balances responsiveness to drift against compute cost, tuning decision thresholds (for example a confidence threshold for auto-answering an FAQ) to trade precision for automation rate, and managing labeling rate and quality control because they directly impact retraining efficacy. Instrumentation is essential: capture fresh examples, provenance, and ground truth so model updates are traceable—without that telemetry, ML’s adaptability is unusable. Finally, recognize the recommendation boundary conditions: avoid ML when the task is unethical to automate, when simple non-ML solutions suffice, or when ML is not cost-effective; nonetheless, evaluate partial ML decompositions as a compromise that can deliver value while limiting risk.

Machine Learning Use Cases

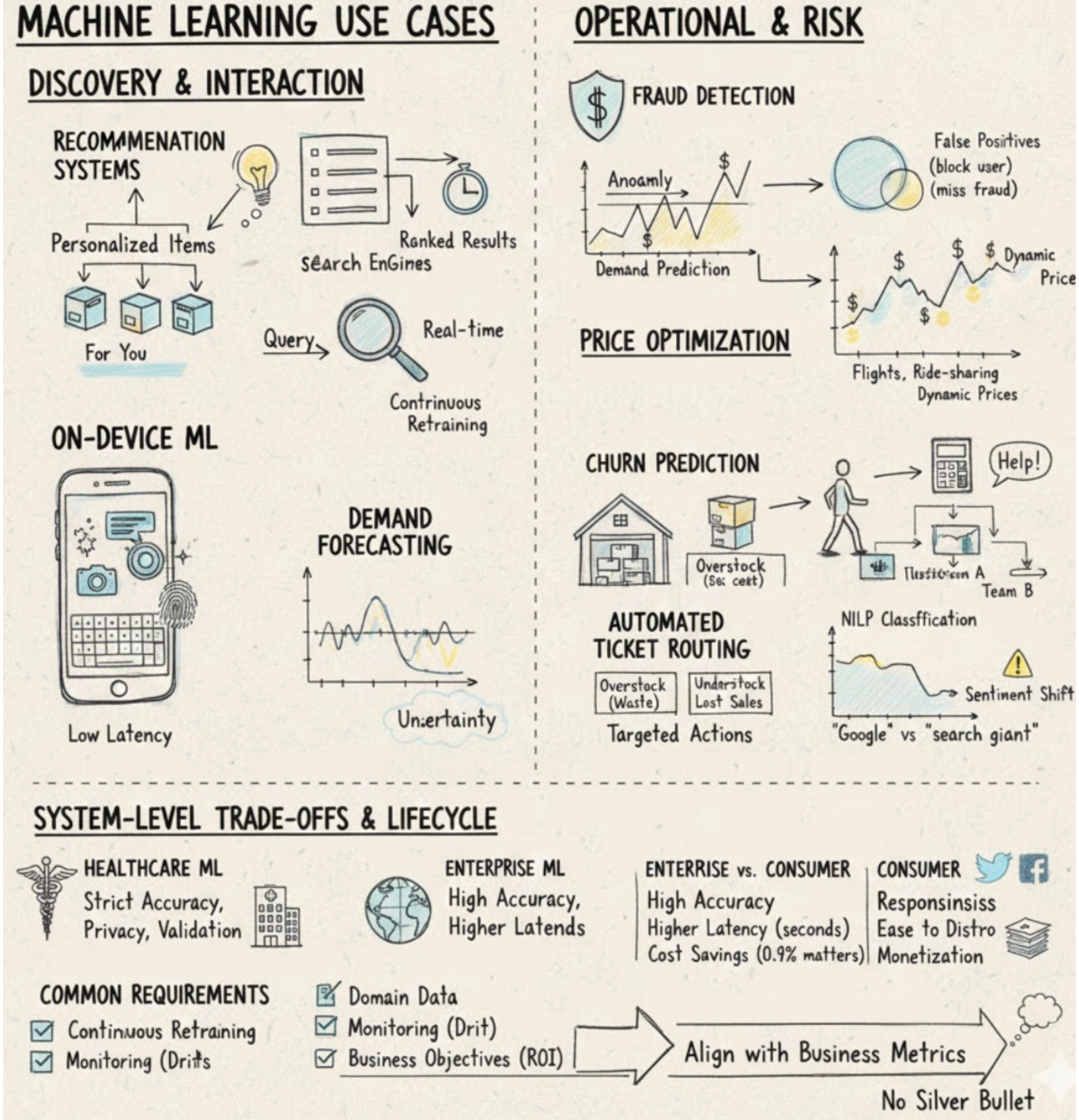

Organizations face two broad, recurring problems: how to help users find what they want amid overwhelming information, and how to make operational decisions that respond to changing demand and behavior. Machine learning addresses the discovery problem by powering recommendation systems and search engines that predict items or rank results to match user intent, reducing information overload and improving relevance. These are related but distinct applications: recommenders infer personalized items from behavioral signals, while search ranks content that matches a query. Both rely on large-scale user/item signals and real-time or near-real-time scoring pipelines to deliver timely, relevant experiences. In user-facing interfaces, on-device ML (examples: predictive typing, photo enhancement, fingerprint/face authentication) embeds models directly into UI/UX flows where low-latency inference and robustness to noisy input are required; this tight coupling with interaction design shapes constraints on model size, latency, and error tolerance.

Beyond discovery, ML tackles a range of operational and risk problems that require different modeling choices. Fraud detection typically blends anomaly detection with supervised classification over historical transactions; designers must trade off false positives (which block legitimate users) against false negatives (which miss fraud), and keep models resilient by continuously retraining on new fraud patterns. Price optimization uses demand predictions to set dynamic prices to maximize objectives like margin or revenue; it works best in high-volume, demand-fluctuating domains (ads, flights, accommodation, ride-sharing) and depends on throughput, accurate elasticity-of-demand modeling, and careful objective specification to avoid adverse business effects. Similarly, demand forecasting is a time-series problem used for stock and capacity planning: forecast errors lead to overstock (waste, perishables) or understock (lost sales), so models must quantify uncertainty and integrate tightly with inventory and budgeting systems. Customer lifecycle tasks are another common class: churn prediction estimates attrition likelihood to trigger targeted retention actions and can produce outsized financial gains because acquisition is expensive (for example, \$86.61 per paying app user or about \$158 per Lyft rider, and acquiring a new user costs 5–25× more than retaining one). Text-oriented problems such as automated ticket routing use classification and NLP to map support requests to teams, requiring labeled historical tickets, latency compatible with support workflows, and periodic updates for new issue types. For public-facing reputation monitoring, brand monitoring combines entity recognition and sentiment analysis to detect explicit and implicit mentions (for example, “Google” vs. “the search giant”) at scale over streaming social data and to alert on sudden sentiment shifts.

These use cases reveal recurring system-level trade-offs and lifecycle requirements. In regulated domains, healthcare ML demands stricter accuracy, privacy, and deployment constraints than many consumer apps; because failures carry safety and regulatory consequences, models are delivered via healthcare providers and require rigorous validation and privacy controls. More generally, enterprise customers often demand higher accuracy and can tolerate higher latency (where seconds may be acceptable), while consumer apps prioritize responsiveness and ease of distribution but face tougher monetization; as a result, even a small relative accuracy improvement (for example, 0.1%) can translate to large enterprise cost savings. Practically, most enterprise ML depends on domain-specific labeled or historical datasets (fraud logs, transaction volumes, support tickets, brand mentions), continuous retraining to adapt to distribution shifts, monitoring for drift and failures, and explicit integration with business objectives to measure ROI. Design decisions should therefore align latency, throughput, and model lifecycle practices with the specific business metric you intend to move—because the right technical trade-offs depend less on algorithmic novelty and more on fitting models into real operational and economic constraints.

Understanding Machine Learning Systems

Machine learning in production shifts the design conversation away from architectures alone and toward data as the primary design variable: the amount of data you collect, the quality and consistency of its labels, and the distribution it represents are often the levers that most strongly determine a model’s behavior. This matters because an ML system is not a single artifact but a pipeline where upstream choices feed downstream outcomes. To reason about that pipeline, it helps to decompose scope into data-centric stages (collection, labeling, validation), model-centric stages (training, evaluation), and system-centric stages (serving, monitoring, retraining). Each stage consumes the outputs of the previous one, so poor labeling or skewed collections propagate through training and surface as production failures. In contrast to academic ML, which optimizes for algorithmic novelty and benchmark scores, production ML must trade those research goals for operational constraints — latency, throughput, cost — and for robustness and maintainability. Likewise, unlike deterministic traditional software, ML components produce probabilistic outputs learned from data, which creates non-determinism, tight coupling to input distributions, and testing patterns that must be data-aware rather than purely unit-test driven.

Because model quality ties directly to the data pipeline and to serving infrastructure, responsibilities shift: data engineers and labelers, ML engineers, and SREs must collaborate closely. This leads to operational patterns and trade-offs you will make repeatedly. For example, you balance model accuracy against compute costs for both training and inference; you decide between replacing a model instantly (favoring consistency) or rolling it out gradually with canarying or A/B tests (favoring availability and risk control); and you weigh development speed against reproducibility and traceability, which drives data and model versioning. These lifecycle differences mean ML development is inherently iterative and continuous — collect data, retrain, redeploy — so you need automated retraining triggers, versioned datasets and models, and deployment practices that expect change. Without those practices, common ML failure modes emerge: dataset shift or concept drift where the input distribution moves over time; label noise that corrupts what the model learns; training-serving skew when features are computed differently in training versus production; and silent degradation, where performance erodes unnoticed. As a result, runtime monitoring, drift detection, and human-in-the-loop remediation become first-class operational requirements.

Performance and measurement considerations further separate ML systems from typical software projects. Training is largely compute- and IO-bound: throughput and distributed scaling determine how quickly you can iterate on large datasets. Serving, in contrast, is latency-sensitive — model size, batching behavior, and hardware choices directly affect P99 inference latency — so scaling strategies for training and serving diverge. Measurement also changes: research metrics and benchmark accuracy are necessary for model development but insufficient for production. You must instrument business-oriented metrics, run real-user experiments, and continuously monitor to detect regressions that static benchmarks miss. Taken together, these points motivate a systems-oriented treatment: production ML introduces system-level concerns — pipelines, monitoring, deployment patterns, and cross-functional roles — that mean traditional software engineering and ML research provide important tools but not a complete solution. Embracing that systems perspective lets you manage the trade-offs and operational risks that determine whether a model continues to deliver value after it leaves the lab.

Mind vs. Data

Machine learning teams routinely face a fundamental strategic choice: should they spend scarce engineering time encoding structure into models, or should they instead invest in collecting and computing on ever more data? Framing this as a choice between “mind” and “data” makes the trade-off explicit. “Mind” means deliberately building inductive structure into models — for example, using inductive biases, causal inference frameworks, or Bayesian networks — so systems can learn reliably from limited examples. “Data” means using simple, general-purpose learners and letting scale (more labeled examples plus more computation) discover patterns without heavy human encoding. This matters because, in realistic projects, neither time nor compute is infinite: where you allocate engineering effort determines whether your system will generalize efficiently from few examples or leverage massive data to outperform bespoke designs.

Understanding how these approaches work in practice requires looking at their resource and failure characteristics. A “mind”-first design increases sample efficiency: by constraining hypothesis space with structural priors or causal reasoning, you reduce the amount of data needed to generalize correctly. In contrast, a “data”-first strategy relies on sheer scale; as Richard Sutton argues, general methods that exploit compute and large datasets can win in the long run because they scale with available computation. But scale comes with costs: more data drives up storage, I/O, and compute demands and forces architecture choices such as distributed training and large-scale storage systems. Concrete benchmarks show how steep that scaling is: One Billion Words was roughly 0.8B tokens in 2013, GPT-2 about 10B tokens in 2019, and GPT-3 around 500B tokens in 2020. These numbers illustrate why a data-centric path requires substantial investments in pipelines and infrastructure.

From an engineering perspective, data work is foundational: advanced modeling is brittle without robust upstream systems. Monica Rogati’s Data Science Hierarchy of Needs — Collect → Move/Store → Explore/Transform → Aggregate/Label → Learn/Optimize → AI/Deep Learning — captures this dependency chain. Instrumentation, ETL, storage, cleaning, feature aggregation, and labeled datasets are prerequisites: if collection or labeling is poor, even the most capacious model produces garbage-in/garbage-out. Prioritizing data quality and quantity therefore implies heavy investments in logging, anomaly detection, labeling processes, and governance. Conversely, leaning toward structural modeling demands concentrated human effort to craft inductive biases and causal models, which reduces capacity to scale datasets and compute in the same time window. Christopher Manning warns of “bad learners” when algorithmic structure is too simple, while proponents of structural priors argue these designs outperform data-heavy approaches under finite-data regimes.

These trade-offs determine when each strategy is preferable and what risks you accept. When data is scarce or when safety and causal interpretability matter, favoring the “mind” — explicit structure and causal reasoning — improves sample efficiency and gives clearer failure modes. When large, high-quality datasets and ample compute are available and rapid empirical scaling is feasible, favoring the “data” approach can deliver superior performance but requires heavy investment in infrastructure and governance to avoid brittle systems. The debate also has temporal stakes: some predict structural methods will regain prominence quickly, others predict compute-leveraging general methods will eventually dominate, reflecting strategic uncertainty for where organizations should invest. In short, practical ML engineering is about balancing human design and data scale: choose structure to get more from less data, or choose scale and engineering to let general methods learn from abundance — but only after you’ve secured the foundational layers that make either path reliable.

Language model datasets over time (log scale)

Over the past decade the quantity of text used to train language models has not increased linearly but multiplicatively: on a log scale the exponential data growth is clear. This matters because larger training-data volumes are themselves a historical driver of progress in deep learning—many recent gains in model capability track closely with increased corpus size. In other words, feeding models much more data has been one of the principal levers for improving performance, and the dataset-size trend therefore shapes research choices and engineering priorities across model design, compute provisioning, and data collection.

At the same time, more data is not an unalloyed good. The relationship from raw data volume to accuracy is non-monotonic: simply adding examples does not guarantee better models. That arises from a classic quality-versus-quantity trade-off — when additional examples are lower quality they can actively harm learning rather than help. Two concrete failure modes illustrate why: outdated data, which creates a temporal mismatch between training and the current target distribution, and incorrect labels, which inject label noise into supervised signals. Outdated data produces a distribution mismatch that reduces generalization to present-day tasks, while incorrect labels produce noisy gradients that slow or misdirect optimization and corrupt the supervision the model needs to learn the right patterns.

These harms have practical consequences. Because training cost scales with dataset-size, ingesting large volumes of low-quality data increases compute, time, and monetary cost without commensurate gains and can reduce a model’s effective sample efficiency. As a result, exponential dataset growth forces stronger data engineering: freshness checks, label validation, filtering and deduplication become essential controls to prevent scale from producing regressions. Given limited compute and resources, the practical prioritization is clear—collecting and preserving high-quality, relevant data yields better returns than indiscriminate volume growth, and marginal low-quality examples can be net-negative to model performance.

Machine learning work in research and in production answers different questions, so they optimize for different outcomes. In research the priority is training throughput and experimental agility: you want fast training loops, many epochs, large batches, and tunable gradient-descent pipelines so you can compare algorithms on repeatable train/test splits. In production the priority flips to fast inference and low-latency, highly available responses for real users. As a result, architecture and resource allocation change: what looks like a distributed GPU/TPU cluster to maximize compute utilization in research becomes a highly responsive serving stack with horizontal replication, autoscaling, and tight latency SLOs in production. This mismatch also creates an evaluation gap—offline metrics that look good on a static test set often fail to predict real-world behavior when inputs are changing or models affect user behavior.

To bridge that gap, production ML treats data and operations as first-class concerns. Because production data is non‑stationary, systems must continuously validate inputs, detect distributional changes, and keep features consistent across training and serving. This leads to a pipeline that connects ingestion → validation → feature materialization → training/serve, with components such as a feature store (for consistent feature materialization), data validators (schema and distribution checks), and drift detectors (statistical tests and thresholds). Production also integrates operational controls around fairness and interpretability—fairness audits, bias mitigation, and explainability tools become part of evaluation and monitoring, which adds latency and complexity but is operationally necessary. On the serving side, architects use model compression techniques (quantization, distillation, operator fusion, caching, sharding) to reduce inference cost and latency; these methods improve throughput but may degrade accuracy or interpretability, so they must be balanced against validation and rollback strategies. Similarly, batching incoming requests raises throughput at the cost of higher tail latency, forcing a trade-off between cost efficiency and SLA compliance.

Operational resilience and observability determine whether a deployed model stays useful. Production failure modes include dataset shift, train/serve skew (differences in feature computation between offline training and online serving), silent data corruption, feedback loops where the model changes the distribution it sees, and gradual model degradation. To mitigate those risks systems add end‑to‑end tests, feature validation, shadow or canary deployments, and automatic rollback procedures. Observability goes far beyond loss and accuracy: you must monitor latency and throughput, input feature distributions, label (ground‑truth) latency, model score distributions, fairness metrics, and relevant business KPIs, with tuned thresholds and alerting rules for drift sensitivity and degradation. Scaling strategies reflect different cost profiles: training is scaled out for throughput (data or model parallelism) and tends to be episodic and compute‑intensive, whereas serving is scaled out with replication and request routing and is a continuous cost-per-request. There is also a design choice between online learning (continual updates that reduce freshness lag but increase complexity and safety risks) and periodic retraining (simpler validation but slower adaptation). Finally, production ML embeds software-engineering practices missing from many research workflows — CI/CD for models, reproducible artifact storage and data lineage, controlled canary/A–B rollouts, and runbooks—to trade development velocity for governance and reliability. Taken together, these practices close the loop between offline research and live behavior, making ML systems maintainable, auditable, and robust in the face of real-world change.

Different stakeholders and requirements

Engineering teams rarely optimize for a single truth: product decisions sit at the intersection of many stakeholders with competing objectives. ML engineers want the best predictive accuracy, sales care about revenue per order, product owners impose strict latency targets, infrastructure teams demand reliability and maintainability, and management focuses on margins. These differing priorities create a situation where what looks like a better model on one axis can be objectively worse on another. For example, one approach (model A) might maximize click probability while another (model B) targets app revenue; because those objectives are orthogonal they produce different item rankings and even different model architectures. Without an explicit process to prioritize or reconcile objectives, teams will make deployment choices that satisfy some stakeholders while violating others.

A practical approach to this multi-objective tension is decoupling objectives: train specialized models for each stakeholder objective and combine their outputs downstream. That separation preserves interpretability — each model remains closely tied to a single business metric — and lets teams iterate independently. In practice, combining predictions then becomes a system-design problem: you must choose an aggregation strategy (for example, weighted scoring or constrained optimization), accept additional latency and complexity from multiple model calls, and maintain a clear contract about how trade-offs are resolved. This trade-off is particularly stark when product constraints are hard. If product requires a latency SLA of under 100 milliseconds and you know abandonment rises by 10% above that threshold, you must treat latency as a must-have constraint: higher-performing but slower models are effectively ineligible. If latency is only a nice-to-have, you can entertain slower models but only after quantifying the user impact.

Operational realities further constrain model design and rollout. Infrastructure teams who see nightly scaling alerts will prioritize platform stability and may freeze model updates to reduce operational risk; this creates a direct tension between model freshness/experimentation and reliability. Similarly, techniques that shine in research — ensembling being the canonical example — often increase prediction latency, system complexity, and maintenance cost. The Netflix Prize winners illustrate this: ensembling delivered better offline metrics but ensembles are rarely practical in production because of these operational costs. Deciding whether to accept that added complexity requires a cost–benefit judgment: a 0.2% lift in CTR might translate to millions of dollars and justify complex engineering, whereas a 0.2% absolute improvement in speech recognition from 95.0% to 95.2% is likely imperceptible to users and unlikely to justify extra latency, energy, or maintenance burden.

Finally, be wary of incentives and evaluation artifacts that mask true production value. Leaderboards and shared benchmarks invite multiple-hypothesis testing; when many teams evaluate on the same hold-out set, some reported gains are false positives and do not generalize to your production distribution. Benchmark-driven incentives (seen on platforms like GLUE and Kaggle and discussed in EMNLP 2020) push researchers to maximize single metrics—accuracy, for example—at the expense of deployability concerns such as compactness, fairness, or efficiency. The consequence is a catalog of production failure modes: increased latency, scalability breakdowns under traffic growth, harder debugging, higher energy consumption, and more frequent infrastructure interventions. To avoid these outcomes you must explicitly map stakeholder requirements to evaluation metrics, treat organizational incentives (including managerial cost-cutting or consolidation goals) as real constraints, and codify trade-offs so deployment decisions are defensible across teams.

Computational priorities

When you build machine learning systems, the dominant resource constraint shifts as the system moves from experimentation to production, and recognizing that shift is critical. In early development the bottleneck is development-phase bottleneck: you run many repeated training runs to tune hyperparameters and evaluate candidate architectures, so training wall-clock time and iteration throughput (how many complete training experiments you can run per day) directly govern developer productivity. To move faster you therefore optimize for metrics like time-per-epoch, convergence time, and the total number of experiments completed — improvements here shorten the feedback loop and increase experimentation velocity, which is the primary objective during model development.

This focus changes after deployment because serving predictions continuously becomes the dominant cost — the production-phase bottleneck. Production optimization targets are different: minimize inference latency, maximize throughput (requests/sec and concurrency), and reduce cost per million inferences while meeting SLAs. This lifecycle mismatch creates a real misprioritization risk: techniques that speed up development (for example, larger models that train better per experiment, expensive data augmentation that improves generalization, or heavy ensembling to boost validation scores) often increase inference compute, memory, and latency. As a result, a model tuned exclusively for fast training can become expensive or slow to serve, and conversely a model hand-optimized for minimal inference cost can slow down experimentation. To manage this trade-off, teams must treat serving efficiency — latency, memory footprint, and per-request compute — as first-class constraints during model selection rather than an afterthought.

Those different priorities imply concrete architecture, measurement, and CI choices. Resource provisioning should reflect phase: allocate cluster capacity and scheduling to support many concurrent or long-running training jobs in the experimentation environment, and provision latency-optimized, highly available serving infrastructure in the production environment to meet SLA requirements. Instrumentation must also follow the regime: development telemetry should emphasize time-per-epoch, convergence time, and experiments-per-day so you can detect slow feedback loops, while production telemetry should measure 95/99th percentile inference latency, throughput, request concurrency, and cost metrics to reveal serving bottlenecks. For reproducibility and CI, avoid re-running heavy training unnecessarily inside your continuous integration pipeline; instead scope automated tests to surface regressions cheaply, and design production CI/CD to validate inference performance (latency, memory, behavior under realistic load) not just accuracy on a test set. In practice this leads to an architectural pattern: treat the ML lifecycle as two distinct operating regimes — an experimentation environment optimized for fast training iterations and an isolated serving environment optimized for inference — so you don’t force a single design to serve two conflicting objectives.

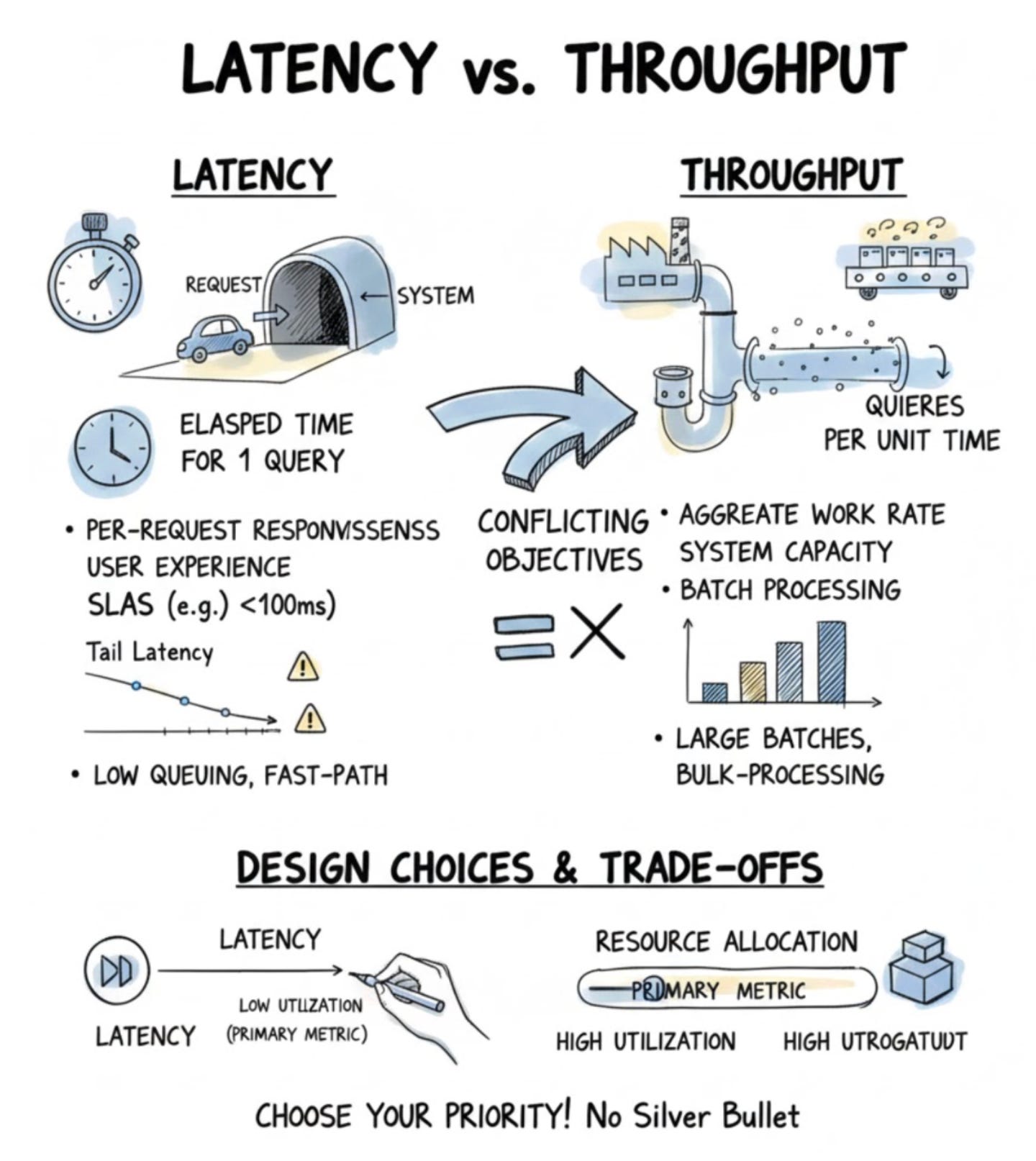

Latency vs. throughput

In distributed systems and services we care about two fundamentally different performance dimensions: Latency and Throughput. Latency measures the elapsed time for a single query — from when the system receives a request to when it returns a result — so it captures per-request responsiveness. Throughput measures the aggregate rate of work over time, i.e., how many queries the system processes per unit time, and therefore expresses capacity and volume. These two metrics answer different operational questions: latency tells you how quickly an individual user sees a response, while throughput tells you how much total work the system can absorb.

Because they answer different questions, systems optimize for one or the other in different contexts. Research systems and data-parallel experiments typically prioritize throughput: they want to process large volumes of data or drive high benchmark numbers, so designs emphasize batching and bulk-processing pipelines that maximize utilization. In contrast, production systems that serve real users prioritize latency and user-perceived responsiveness — often because of SLAs — so they favor low queuing, fast-path optimizations, and aggressive provisioning to keep per-request times down. This leads to divergent design choices: a throughput-oriented change (for example, introducing larger batches) increases aggregate work done per unit time but usually increases the per-request elapsed time; conversely, reducing queuing and over-provisioning lowers latency but reduces resource utilization and aggregate throughput.

Those divergent choices have clear resource-allocation and measurement consequences. Maximizing throughput typically raises utilization and amortizes fixed costs across many queries, which is economical for batch and benchmark workloads. Minimizing latency often requires accepting lower utilization: you may run more parallel, statically provisioned capacity or perform precomputation so individual requests see minimal delay. Correspondingly, the optimization targets differ: throughput tuning looks at aggregate rates and end-to-end capacity numbers, whereas latency tuning requires per-request timing, attention to tail-latency, and tight monitoring against SLAs. As a result, the instrumentation and feedback loops you build for each goal are different — one tracks average or sustained rates, the other tracks distributions and worst-case per-request times.

The practical takeaway is that you cannot generally maximize both simultaneously; they are often conflicting objectives. Therefore, when designing or tuning a system, explicitly choose which metric is primary and accept degradation in the other as a consequence. This means ranking objectives up front and letting that ranking drive architectural patterns (batch vs fast-path), resource allocation (high utilization vs reserved capacity), and which metrics you measure and optimize. Doing so makes trade-offs deliberate rather than accidental and aligns system behavior with the real priorities of research experiments or production user experience.

TERMINOLOGY CLASH

When engineers discuss performance they often run into a simple but consequential terminology clash: different authors define the same words differently. One common split contrasts Kleppmann’s usage, which separates response time (the client-observed, end-to-end interval that includes network, queueing, and service) from latency (just the service’s internal wait or processing time). This text instead collapses those terms and defines latency as the client-observed wall-clock interval from when a request is sent until a response is received — explicitly including network transfer, queueing, and processing — because that matches the machine-learning community’s usage and keeps discussions about user experience straightforward.

With that definition in place, the relationship between latency and throughput becomes easier to reason about. For a system that processes one request at a time, throughput is roughly the reciprocal of average latency: throughput ≈ 1 / average_latency, so 10ms average latency corresponds to about 100 queries/sec and 100ms to about 10 queries/sec. Introducing batching disrupts that simple inverse because the system processes multiple requests together. If a batch of 10 requests completes in 10ms, the average per-request latency remains 10ms while throughput jumps to about 1000 qps; if a batch of 100 takes 50ms, average latency becomes 50ms and throughput rises to 2000 qps. This gives a powerful lever to increase hardware utilization, but it comes with a key complication: online-batching requires the system to wait for enough arrivals to form batches, which adds queueing delay and raises client-observed latency. As a result, batching is a deliberate trade-off between raw throughput and the latency users experience.

Those trade-offs drive different priorities in research and production. Research work typically optimizes throughput — samples/sec — and will accept higher per-sample latency through aggressive batching to maximize hardware efficiency. Production systems, however, prioritize low user-observed latency because small increases in latency measurably hurt business metrics: studies show that 100ms extra delay can reduce conversions by about 7% (Akamai, 2017), modest latency increases can nudge conversion down (Booking.com, 2019), and page loads over 3s cause more than 50% mobile abandonment (Google, 2016). In practical terms, minimizing latency by processing single samples often underutilizes parallel hardware and raises cost per sample, while maximizing throughput with large batches improves utilization but can degrade user experience and therefore revenue.