Building a Financial Pattern Recognition Engine

separating true market signals from noise using Density-Based and Probabilistic Machine Learning models.

Download the source code using the link at the end of the article!

Financial markets are rarely static; they cycle through evolving regimes defined by shifting correlations, volatility spikes, and liquidity crunches. However, defining these regimes historically relies on discretionary labels or simplistic heuristics that often lag behind reality. To capture the true, latent structure of the market, we must move beyond supervised learning and allow the data to speak for itself. This article constructs a comprehensive Unsupervised Learning pipeline designed to uncover hidden patterns in financial time series. By moving from dimensionality reduction techniques like PCA to a comparative analysis of clustering algorithms — ranging from the spherical assumptions of K-Means and the probabilistic nature of Gaussian Mixture Models to the density-based precision of HDBSCAN — we demonstrate how to transform raw, noisy market features into distinct, actionable market regimes. We will explore not just the theoretical underpinnings of these methods, but the practical code required to implement, validate, and visualize them.

Overview of Clustering Algorithms

Both clustering and dimensionality reduction are techniques for summarizing data. Dimensionality reduction compresses the data by representing it with fewer, new features that retain the most relevant information. Clustering, by contrast, groups existing observations into subsets of similar data points.

Clustering helps reveal structure in data by creating categories from continuous variables and enables automatic classification of new objects according to those learned criteria. Common applications include hierarchical taxonomies, medical diagnostics, and customer segmentation. Clusters can also be used to produce representative prototypes — for example, using a cluster centroid as a representative sample — which is useful in applications such as image compression.

Clustering algorithms differ in their strategy for identifying groups:

- Combinatorial algorithms search among alternative partitions to select the most coherent grouping.

- Probabilistic models estimate the distributions that most likely generated the clusters.

- Hierarchical methods produce a sequence of nested clusters, optimizing coherence at each level.

Algorithms also vary in the notion of what constitutes a useful grouping, which should align with the data characteristics, domain, and application goals. Common grouping types include:

- Clearly separated groups of various shapes

- Prototype- or center-based, compact clusters

- Density-based clusters of arbitrary shape

- Connectivity- or graph-based clusters

Other important aspects of a clustering algorithm include whether it:

- requires exclusive cluster membership,

- produces hard (binary) versus soft (probabilistic) assignments, and

- is complete in the sense of assigning every data point to a cluster.

from warnings import filterwarnings

filterwarnings(’ignore’)These two lines globally silence Python’s warning system so that any warning issued by libraries or your own code will not be printed to stdout/stderr. In a pipeline for unsupervised market-pattern discovery and clustering you will typically see many non-fatal warnings from numerical libraries, scikit-learn, pandas, or visualization tools — things like deprecation notices, convergence hints, dtype coercions, or warnings about ill-conditioned inputs — and the call to filterwarnings(‘ignore’) is a blunt way to remove that noise so logs and notebook outputs stay clean.

That choice has practical motivations: when running long experiments or producing reports for stakeholders you may prefer uncluttered output; third‑party libraries can generate repeated or low‑value warnings that distract from key metrics; and in demo environments presentation clarity is often prioritized. However, because warnings are early signals of issues that do not stop execution, globally ignoring them also hides useful diagnostics. In this domain that can be dangerous: warnings about empty clusters, failed convergence, numeric overflow/underflow, or type coercions can indicate data quality problems, bad feature scaling, or algorithm misuse that materially change clustering results and downstream pattern discovery.

A safer pattern is to be deliberate about which warnings you suppress and when. During development and validation keep warnings visible so you can catch data drift, preprocessing bugs, or model instability. In production or presentation contexts, suppress only specific categories or modules (for example DeprecationWarning from a known library you accept, or a noisy message from a plotting backend) or use a local suppression context so that only the noisy callsite is silenced. Alternatively, route warnings into your logging system so they are recorded and searchable even if not printed. In short: the code here achieves a clean run by ignoring all warnings, but that convenience trades off early diagnostics that are important for reliable, interpretable unsupervised learning and should be replaced with more targeted handling once the pipeline is mature.

%matplotlib inline

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import pandas as pd

from numpy.random import rand, seed

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

from sklearn.neighbors import kneighbors_graph

from sklearn.datasets import make_blobs, make_circles, make_moons

from matplotlib.colors import ListedColormap

from sklearn.cluster import KMeans, SpectralClustering, DBSCAN, AgglomerativeClustering

from sklearn.mixture import GaussianMixture

from sklearn.metrics import adjusted_mutual_info_score

import seaborn as snsThis block of imports sets up a small laboratory for iteratively developing and validating unsupervised clustering methods for market-pattern discovery. At a high level the intended flow is: generate or load market-like data (pandas / synthetic generators), normalize it so distance measures are meaningful (StandardScaler), construct similarity/connectivity structures when needed (kneighbors_graph), apply a variety of clustering algorithms (centroid-based, graph-based, density-based, hierarchical, probabilistic), compare and validate results (adjusted_mutual_info_score), and finally visualize outcomes (matplotlib / seaborn / ListedColormap). Each import supports a specific role in that pipeline.

We explicitly include numpy.random.seed and rand to control and inject random variation reproducibly. In exploratory work with market data you’ll often prototype on synthetic datasets to understand algorithm behavior — make_blobs, make_circles and make_moons produce canonical clustering shapes (spherical, concentric, and crescent-shaped) that reveal strengths and failure modes of different clustering methods. Using a fixed seed ensures experiment reproducibility, which is important when tuning hyperparameters like k, eps (DBSCAN) or affinity parameters for spectral methods.

StandardScaler is included because almost every clustering method here is distance- or variance-sensitive. Normalizing features to zero mean and unit variance prevents any single feature (e.g., absolute price level vs. short-term volatility) from dominating Euclidean or Mahalanobis-like distances. In a market context this is why we typically cluster on returns, normalized indicators, or PCA components rather than raw prices: scaling makes cluster assignments more reflective of pattern shape than scale.

kneighbors_graph constructs the local-neighborhood adjacency matrix that spectral clustering needs as an affinity approximation and that agglomerative clustering can use as a connectivity constraint. This graph is the mechanism by which we translate local similarity into a global structure; choices like number of neighbors or whether the graph is symmetric materially change the spectrum and therefore the clusters SpectralClustering produces. That’s why we bring this utility in early: it’s a tunable bridge between raw features and graph-based methods.

The set of clustering algorithms reflects complementary assumptions you’ll want to test against market data. KMeans is fast and interpretable but assumes roughly spherical clusters of similar size; use it when you expect regime centers or prototype patterns. SpectralClustering converts local similarities into a low-dimensional eigenembedding and can recover complex non-convex groupings (useful for irregular pattern shapes). DBSCAN is density-based and identifies arbitrarily shaped clusters while explicitly marking noise/outliers — valuable for spotting anomalous market behavior. AgglomerativeClustering gives a hierarchical view and can enforce connectivity constraints from kneighbors_graph, which is useful when you want a dendrogram-style analysis of pattern granularity. GaussianMixture models produce soft/ probabilistic assignments and per-cluster covariances, which let you reason about confidence and the shape/overlap of discovered regimes.

adjusted_mutual_info_score is included to compare clusterings in a principled way. Since labels in unsupervised learning are arbitrary permutations and market ground truth is often absent, AMI is useful when you want to (a) compare an algorithm to a synthetic ground truth, or (b) measure similarity between two clustering runs (e.g., before/after preprocessing or across hyperparameter sweeps). Unlike raw accuracy or simple matching, AMI corrects for chance and is label-invariant.

Finally, matplotlib, seaborn and ListedColormap plus pandas form the display and data-management layer: pandas for ingesting and shaping time-series or feature matrices, seaborn for higher-level, publication-ready visualizations of cluster structure, and ListedColormap to control color mapping when plotting cluster labels. The notebook magic (%matplotlib inline) simply keeps plots visible during iterative exploration.

Practical notes and cautions: scaling choice matters (StandardScaler is a sensible default but consider RobustScaler if outliers dominate), spectral methods require careful tuning of neighborhood/affinity to avoid spurious splits, DBSCAN’s eps/min_samples are highly data-dependent, and KMeans/GMM require you to pick k (so use elbow/silhouette/AMI comparisons or stability checks). For market pattern discovery you’ll usually precompute features that capture shape (returns, rolling statistics, wavelet/PCA components) before feeding this pipeline; the imports here give you the tools to prototype that end-to-end workflow and to compare algorithmic assumptions against the empirical structure of your market features.

sns.set_style(’white’)

seed(42)The first line, sns.set_style(‘white’), configures the global plotting aesthetic so all subsequent Seaborn/Matplotlib figures use a clean white background and minimal visual clutter. For market-pattern discovery and clustering this matters because we rely heavily on visual inspection — heatmaps, scatter plots of embedding spaces, cluster-centroid overlays — to validate and communicate patterns. A white style removes distracting gridlines and colored backgrounds that can obscure subtle structure in dense plots, making differences between clusters and temporal patterns easier to perceive and more consistent across figures and reports. It’s a purely presentation-level change (it does not affect data or algorithms), but setting it once at the top ensures consistent, publication-ready visuals throughout an analysis.

The second line, seed(42), fixes the random number generator so that later stochastic operations are repeatable. In unsupervised workflows you frequently encounter randomness: initial centroid placement in K-means, random subsets in sampling or bootstrap, stochastic initializations in mixture models, the random component of dimensionality-reduction techniques (e.g., random projections, certain t-SNE/UMAP runs), and any shuffling used for cross-validation or bootstrapping. By setting a seed you make experiment outputs deterministic for debugging, for comparing algorithm variants, and for producing reproducible figures and metrics. Note that “seed(42)” must be the call that targets the actual RNG your code uses (e.g., numpy.random.seed, Python’s random.seed, or the RNG seeding functions of libraries like PyTorch/Scikit-learn); if multiple RNGs are in play you should set each one explicitly. Also be deliberate about the choice to fix randomness: it’s excellent for reproducibility and debugging, but when assessing robustness you should run multiple seeds to ensure conclusions are not an artifact of one initialization.

flatui = [”#9b59b6”, “#3498db”, “#95a5a6”, “#e74c3c”, “#34495e”, “#2ecc71”]

cmap = ListedColormap(sns.color_palette(flatui))These two lines are setting up a fixed, discrete color mapping you’ll use when visualizing cluster assignments or other categorical outputs from the unsupervised pipeline. The first line defines an explicit, ordered palette of hex color codes — a small set of visually distinct colors chosen so different clusters or pattern classes are easy to distinguish. By declaring the palette up front you control the aesthetics and ensure consistency across multiple plots (scatter projections, heatmaps, dendrograms, time-series label overlays), which is important when you’re interpreting clusters in market-pattern discovery.

The second line converts that palette into a matplotlib-friendly, discrete colormap. sns.color_palette(flatui) turns the hex strings into normalized RGB tuples (the format plotting libraries expect), and wrapping that sequence with ListedColormap produces a colormap that maps integer indices to the exact colors you provided. This is deliberate: unlike continuous colormaps that interpolate hues across a range, a ListedColormap preserves exact, categorical colors so cluster label 0 always maps to the first color, label 1 to the second, etc. That deterministic mapping avoids visual ambiguity (e.g., gradients suggesting ordinal relationships) and makes legends and colorbars read as discrete categories rather than continuous measures.

From a workflow perspective this matters for interpreting unsupervised results: clear, consistent discrete colors make it easier to track a cluster across dimensionality-reduction plots (t-SNE/UMAP), compare cluster compositions over time, and present stable visuals to stakeholders. A couple practical notes: the order of colors controls label-to-color assignment (so reorder if you want a different mapping), ensure the palette size matches or exceeds your expected number of clusters, and if accessibility is a concern, choose or test palettes for color-blind friendliness.

Generating Synthetic Datasets

n_samples = 1500

random_state = 170These two lines are small knobs that control two important experimental variables: the size of the dataset you operate on and the pseudo‑randomness that governs any stochastic steps in the pipeline. n_samples = 1500 determines how many observations are produced or drawn into the downstream unsupervised workflow. In practice that value directly shapes the signal-to-noise trade-offs you will see: with more samples you increase the chance of capturing rarer market regimes, subtle pattern structure, and stable cluster statistics, but you also increase computational cost, memory use, and the risk of including outdated or non‑stationary data that can muddy cluster interpretations. Choosing 1,500 here is a pragmatic compromise — large enough to allow multiple clusters and substructure to appear reliably for typical simulated or preprocessed market feature spaces, yet small enough to keep iterative experiments (clustering runs, dimensionality reduction, hyperparameter sweeps) responsive.

random_state = 170 fixes the random number generator seed used by any stochastic components that follow (data generation, shuffling, random sampling, initial centroids for k‑means, randomized PCA, etc.). The primary reason to set a seed is reproducibility: it ensures that when you re-run the experiment you get the same synthetic dataset or the same initialization path, which is essential for debugging, for comparing configurations, and for attributing changes to algorithmic choices rather than RNG noise. Practically this means the pipeline’s non‑deterministic branches behave deterministically for that particular value, so results, plots, and cluster assignments are stable across runs.

Two operational caveats follow from these choices. First, a single sample size and a single seed can hide sensitivity: clustering outcomes in unsupervised learning can vary with both dataset composition and RNG state. To gain robust conclusions about discovered market patterns you should treat n_samples as a tunable parameter (or run experiments at multiple sizes) and run multiple seeds to estimate variability — e.g., bootstrap sampling or repeating clustering with different random_state values and aggregating metrics like silhouette or cluster membership stability. Second, for real market time series you often should not randomly sample across time without preserving temporal structure; instead use windowed sampling or stratification so that n_samples reflects realistic temporal coverage of regimes rather than a time‑mixed snapshot.

In short: n_samples controls how much market data the clustering system sees (affecting detectability of patterns and compute cost), and random_state makes the stochastic parts of the pipeline repeatable. Use both intentionally — document the seed, sweep multiple sizes and seeds when assessing pattern stability, and respect temporal sampling constraints when working with real market data.

blobs = make_blobs(n_samples=n_samples,

random_state=random_state)This single call to make_blobs is being used to synthesize a controlled clustering dataset: it samples n_samples points from a mixture of isotropic Gaussian distributions and returns both the feature vectors and the ground-truth cluster labels. By generating data this way we get predictable, well-separated groups that are ideal for exercising and debugging the clustering pipeline — distance computations, normalization, dimensionality reduction, and the clustering algorithm itself — without the mess and unknowns of real market data.

Specifying n_samples determines the dataset size so you can test scalability and statistical stability of your clustering approach; using random_state seeds the underlying RNG to make the generation deterministic, which is crucial for repeatable experiments, hyperparameter tuning and comparisons across algorithm variants. The function returns a tuple (X, y) where X contains the feature vectors and y contains the true cluster assignments; keeping the labels allows you to compute supervised-style evaluation metrics (adjusted rand index, normalized mutual information) to measure how well an unsupervised algorithm recovers expected structure.

We use synthetic blobs here intentionally as a sanity-check and benchmark: they reveal issues like incorrect distance metrics, absence of scaling, or bugs in cluster-assignment logic. However, because make_blobs creates isotropic, Gaussian-shaped clusters, it is a simplification compared to real market patterns, which can be non-Gaussian, heteroskedastic, time-dependent and multi-scale. After verifying the pipeline on blobs, the next steps should include adding heterogeneity (varying covariances, noise, correlated features), constructing time-series-aware features or synthetic pattern generators, and testing robustness to outliers — so that the clustering behavior observed on blobs meaningfully transfers to the goal of discovering real market pattern clusters.

noisy_circles = make_circles(n_samples=n_samples,

factor=.5,

noise=.05)This single line generates a synthetic two-dimensional dataset of two concentric circular clusters and assigns it to noisy_circles. make_circles constructs points on an outer circle and an inner circle; the factor parameter (.5) sets the radius of the inner circle to half the outer circle, so the classes are arranged as two rings with a clear non-linear separation. The noise parameter (.05) adds Gaussian perturbation to each point, which simulates realistic measurement or market noise and makes the cluster boundary fuzzy rather than perfectly circular.

Practically, the function returns a tuple (X, y): X is an (n_samples, 2) array of coordinates and y is a length-n_samples vector of integer labels (0/1) indicating which ring each sample came from. Although labels are produced, in the context of unsupervised learning for market pattern discovery you should treat y as ground truth only for evaluation and diagnostics — your clustering pipeline should not use y during model fitting. The n_samples argument controls dataset size and the draw is stochastic unless you pass a random_state.

Why we use this here: concentric circles are a deliberately non-linearly separable structure that exposes limitations of simple distance-based methods (like K-means) and motivates non-linear or graph-based approaches (spectral clustering, kernel methods, manifold embeddings) that are more appropriate for detecting pattern topology in market data. The factor and noise parameters let us tune difficulty: decreasing factor increases the gap between rings, and increasing noise simulates lower signal-to-noise ratio typical of financial time series, both of which affect algorithm performance and robustness. For reproducible experiments, fix random_state; for realistic robustness testing, vary noise and sample size and then use the supplied labels only to measure clustering quality.

noisy_moons = make_moons(n_samples=n_samples,

noise=.05)This single call is generating a synthetic two‑class dataset known as the “two moons”: two interleaving half‑circles that form a nonlinearly separable shape. The function constructs coordinate pairs describing the two curved manifolds and — by default — also returns class labels identifying which moon each point belongs to. In the context of unsupervised market pattern discovery, we typically discard those labels when training clustering or manifold‑learning algorithms, but keep them for downstream evaluation (ARI, NMI, accuracy against a known ground truth) so we can quantitatively measure how well an algorithm recovers the true nonlinear structure.

The n_samples parameter controls how many samples are drawn from those two manifolds, so it directly affects statistical power, granularity of the pattern and computational cost: more samples give a denser representation of the moons (better approximating continuous market behavior) but require more computation and may amplify overfitting risks in downstream models. The noise parameter (.05 here) injects isotropic Gaussian perturbations into each coordinate, simulating measurement error or idiosyncratic market noise. We add this noise deliberately to avoid a trivially separable toy problem; it forces clustering and embedding methods to be robust to realistic variability and tests whether algorithms can recover manifold structure under perturbation.

Practically, this dataset is chosen because it stresses algorithms that assume convex clusters or linear separability (e.g., k‑means will typically fail to separate the moons correctly), while highlighting methods that capture non‑linear geometry (spectral clustering, DBSCAN, affinity propagation, manifold learning such as Isomap/UMAP). A final operational note: make_moons is stochastic unless you set random_state; if you need reproducible experiments for model comparisons, pass a fixed random_state so the same noisy realization is generated each run.

uniform = rand(n_samples, 2), NoneThis line constructs a synthetic dataset and immediately wraps it in the usual (features, labels) pair shape used throughout the codebase, but intentionally supplies no labels. The first element, rand(n_samples, 2), produces n_samples rows and two feature columns sampled uniformly (typically in [0,1) when using NumPy’s RNG). We choose two dimensions here so the generated points are easy to visualize and to serve as a minimal testbed for clustering/structure discovery algorithms. The second element is None, which is a deliberate placeholder that signals “unlabeled” data to downstream components that expect an (X, y) tuple; downstream code can therefore unpack this into X, y and know to treat y as absent rather than as a valid label array.

Why do this in an unsupervised market-pattern workflow? A uniform point cloud is a natural null model: it represents data with no inherent cluster structure, so it’s useful for sanity checks, baseline comparisons, or algorithm calibration (for example, to verify that a clustering algorithm doesn’t invent structure where none exists, or to estimate false-positive cluster detection rates). Storing the sample as (X, None) keeps it compatible with pipelines and metric functions that accept supervised-style inputs, while making the unsupervised intent explicit. A couple of practical notes: reproducibility depends on the random seed being set elsewhere (use a controlled RNG rather than global rand if determinism is required), and if you want these synthetic points to reflect market-scaled ranges or noise characteristics you should scale or transform the uniform draws accordingly before feeding them into pattern discovery or clustering stages.

X, y = make_blobs(n_samples=n_samples,

random_state=random_state)This line uses scikit-learn’s data generator to create a controlled clustering problem: make_blobs samples n_samples points from a mixture of isotropic Gaussian blobs and returns the feature matrix X (coordinates of each sample) and y (the integer index of the blob each sample came from). In terms of data flow, we request a synthetic dataset, the generator draws points around several cluster centers (by default three unless you override centers), and hands back X for use by the clustering algorithm and y as “ground truth” labels that reflect the true cluster assignments used to generate the data.

We generate this synthetic data for a few practical reasons. First, it gives a simple, reproducible sandbox for developing and debugging unsupervised pipelines: n_samples controls the dataset size so we can test performance and scalability, and random_state fixes the RNG so experiments are repeatable. Second, because make_blobs produces clearly separated, Gaussian-shaped clusters, it makes it easy to validate algorithm behavior and tuning — for example, to check that a clustering method can recover the underlying structure, to compare metrics (adjusted rand index, normalized mutual information) against the returned y, or to visualize decision boundaries while iterating on feature transformations and hyperparameters.

At the same time, keep in mind why this is only a starting point for market pattern discovery. Real market data exhibit non-Gaussian tails, heteroskedasticity, temporal dependence, and regime shifts that make clustering harder than clean blobs. Use these synthetic blobs to validate implementation, unit-test evaluation code, and establish baseline behavior, but then progressively increase realism — vary cluster_std, add anisotropy or noise, increase dimensionality, or switch to generators that simulate heavy tails — and ultimately validate on real market features. Importantly, in the unsupervised workflow you feed only X into clustering, while y is retained solely for benchmarking and diagnostics during development.

elongated = X.dot([[0.6, -0.6], [-0.4, 0.8]]), yThis single line takes your original feature matrix X and applies a fixed 2×2 linear map to produce a new, “elongated” feature representation, then pairs that transformed feature matrix with y as a tuple for downstream use. Concretely, X must be n×2 so X.dot([[0.6, -0.6], [-0.4, 0.8]]) yields an n×2 matrix whose rows are linear combinations of the original feature axes; the trailing “, y” simply packages the transformed features with the label vector so you can still evaluate or visualize results against ground truth if needed (note: for true unsupervised training you wouldn’t feed y into the learner, only into evaluation).

Why do this? The chosen matrix is not arbitrary: its eigenvalues are 1.2 and 0.2, so the transform stretches data along one principal direction and compresses it along the orthogonal direction (hence “elongated”). That intentionally introduces anisotropic variance and a dominant direction in feature space, which is useful when experimenting with market-pattern discovery because many market phenomena are directional (correlated movements across instruments or scaled latent factors). In practice this does three things for your unsupervised pipeline: (1) it makes principal directions more pronounced, helping covariance-aware methods (PCA, GMM, spectral clustering) to pick up structure; (2) it creates pathological cases for distance-based methods like k-means where scaling can bias cluster assignments unless you standardize or use an appropriate metric; and (3) because the matrix has nonzero determinant it’s invertible, so no information is lost — only the relative variances change — but the condition number (~6) means noise along the stretched axis will be amplified compared with the compressed axis.

How this fits into the overall goal: by simulating an elongated covariance structure you can test how your clustering and pattern-discovery algorithms respond to directionally driven market signals, compare algorithms that use isotropic distances versus full-covariance models, and verify that preprocessing (whitening/standardization) or model choices are appropriate for the kinds of anisotropic patterns you expect in market data. Finally, be mindful to use y only for validation/visualization in this unsupervised context and consider normalizing or inverting the transform when you want to remove the artificial anisotropy.

varied = make_blobs(n_samples=n_samples,

cluster_std=[1.0, 2.5, 0.5],

random_state=random_state)This line uses sklearn’s make_blobs to synthesize a labeled clustering dataset so we can exercise and validate unsupervised methods under controlled conditions. Internally make_blobs samples points from Gaussian (isotropic) distributions placed at a small number of centers; by returning both the feature matrix and the true cluster labels it gives us a playground where we know the “ground truth” structure even though the eventual algorithms we evaluate will be unsupervised. We use such synthetic data to isolate algorithm behavior (sensitivity to overlap, density, and spread) without the noise and confounders of real market data.

The key argument here is cluster_std=[1.0, 2.5, 0.5], which creates three clusters with very different dispersions: one moderately spread (1.0), one wide and overlapping (2.5), and one tight and compact (0.5). That deliberate imbalance is why we prefer this constructor instead of a single scalar: it simulates heterogeneous market regimes — e.g., stable low-volatility pockets, noisy high-volatility periods, and concentrated recurring patterns — and forces clustering algorithms to cope with unequal variances. Practically, this helps reveal weaknesses in methods that assume equal spherical clusters (KMeans) versus those that model different covariances (Gaussian Mixture Models) or adapt to density (DBSCAN). It also highlights preprocessing needs (feature scaling, variance-stabilizing transforms) and parameter sensitivity when moving to real, heterogeneous market features.

The random_state argument fixes the RNG so experiments are reproducible; when you tune algorithm hyperparameters or compare approaches across runs, deterministic synthetic inputs are crucial for attributing differences to algorithmic behavior rather than sampling noise. Finally, note the operational role of these blobs: they’re not the end goal but a diagnostic tool — the returned samples and labels let us compute objective metrics (ARI, AMI, silhouette conditioned on true labels) and visualize separation in low dimensions, giving confidence about which clustering strategies are suitable before we apply them to unlabeled market data.

default_params = {’quantile’: .3,

‘eps’: .2,

‘damping’: .9,

‘preference’: -200,

‘n_neighbors’: 10,

‘n_clusters’: 3}This small dictionary is a compact set of defaults that steer several distinct decisions in the unsupervised pipeline for market-pattern discovery: how we set local similarity scales, how we form neighborhood structure, how we detect dense regions or exemplars, and finally how many clusters we expect to report. Think of it as parameters that get consulted at successive stages of the pipeline as the raw time-series or feature vectors are converted into a similarity graph and then into cluster labels.

First, quantile = 0.3 is used very early in the flow to pick a robust, local scale from the pairwise distance distribution. In practice we compute pairwise distances between market-window feature vectors and then take the 30th percentile as a characteristic local distance (or as a cutoff for building a similarity kernel). The reason we use a quantile rather than the mean or max is that financial distances are heavy-tailed and contain outliers; using a lower quantile produces a scale that emphasizes the denser, locally relevant neighborhoods and prevents a few extreme distances from blowing up the kernel bandwidth or adjacency thresholds.

Next, n_neighbors = 10 and eps = 0.2 control how we convert that local scale into an explicit neighborhood graph or density criterion. n_neighbors defines the k in a k-NN graph (or a local smoothing radius for manifold embeddings such as UMAP or spectral methods): choosing 10 captures short-term/short-range market pattern relationships without immediately fusing distant regimes. eps is the radius/distance threshold used by density-based steps (e.g., DBSCAN-like filtering) — in normalized distance units a small eps (0.2 here) forces clusters to be formed only from fairly tight groups of similar windows. Together these two parameters determine graph connectivity and therefore the granularity of the structures we will be able to discover: increase them to find coarser, broader regimes; decrease them to focus on very tight, repeating micro-patterns.

The dictionary also includes damping = 0.9 and preference = -200, which are parameters you would consult if using an exemplar-based method such as Affinity Propagation to discover representative patterns. Damping close to 1 slows and stabilizes the iterative message-passing updates — important for noisy financial similarity matrices where oscillations are common — while a negative, relatively large-magnitude preference biases the algorithm toward fewer exemplars (each exemplar corresponds to a prototypical market pattern). The absolute value of preference must be interpreted relative to the similarity scale set earlier (the quantile-derived kernel); in other words, -200 here is intentionally low to avoid exploding the number of exemplars given the similarity values we produce.

Finally, n_clusters = 3 is the target or baseline number of groups we expect to interpret downstream (for example as market regimes or risk-return pattern families), and it is used when a fixed-cluster algorithm (like KMeans) is applied to an embedding or when we want a controlled summary of the results for reporting. Note that when using density- or exemplar-based algorithms that determine cluster count automatically, n_clusters may serve only as a sanity-check or a parameter for post-processing (e.g., merging small clusters until we reach this target).

Operationally the pipeline guided by these defaults looks like: compute distances → extract a robust local scale via quantile → build a k-NN / affinity graph with n_neighbors and eps → optionally run an exemplar method with damping/preference or a density method using eps → optionally refine or reduce to n_clusters for interpretation. These values are intentionally conservative starting points for market data: quantile and n_neighbors keep the focus local, eps enforces tightness of patterns, damping/preference stabilize and control exemplar counts, and n_clusters provides a human-interpretable summary size. When tuning, monitor distance histograms, graph connectivity, cluster sizes, silhouette/stability metrics and exemplar interpretability — adjust the quantile if the scale is too global, eps/n_neighbors if the graph is too sparse or too dense, and preference/damping if the exemplar solver oscillates or produces too many/few prototypes.

datasets = [(’Standard Normal’, blobs, {}),

(’Various Normal’, varied, {’eps’: .18, ‘n_neighbors’: 2}),

(’Anisotropic Normal’, elongated, {’eps’: .15, ‘n_neighbors’: 2}),

(’Uniform’, uniform, {}),

(’Circles’, noisy_circles, {’damping’: .77, ‘preference’: -240,

‘quantile’: .2, ‘n_clusters’: 2}),

(’Moons’, noisy_moons, {’damping’: .75,

‘preference’: -220, ‘n_clusters’: 2})]This small block is a compact registry that pairs six synthetic data scenarios with any algorithm hyperparameters that make sense for them. Conceptually it’s a list of cases the clustering pipeline will iterate over: each entry is (label, dataset_array, params_dict). The label is just human-readable for plots or logs, the dataset_array (blobs, varied, elongated, uniform, noisy_circles, noisy_moons) is the X matrix for that scenario, and the params_dict contains algorithm-specific settings you’ll apply when fitting a clustering method on that dataset. An empty dict means “use the algorithm defaults”; non-empty dicts encode manual tuning that produced sensible results for that particular shape.

Why we do this: different cluster geometries and density regimes require different hyperparameters and sometimes different algorithms. By keeping those choices next to the dataset they apply to, the pipeline can programmatically pick up sensible settings instead of brittle one-size-fits-all defaults. Practically, the code that consumes this list will loop over entries, load X, instantiate or configure a clustering model (or a family of models) and update its configuration with the params_dict before fitting and labeling. That keeps the flow tidy: data → dataset-specific config → fit → labels → evaluation/visualization.

How the specific entries map to intent (and why those parameters look the way they do): “Standard Normal” (blobs) represents compact, spherical clusters — most algorithms and default settings work here so no overrides are necessary. “Various Normal” and “Anisotropic Normal” model heteroskedastic or stretched clusters; they include small-radius and neighbor-related settings (eps, n_neighbors) because density-based or graph-based clustering depends sensitively on neighborhood size — smaller eps or neighbor counts help detect tight or elongated groups without merging distinct clusters. “Uniform” is a structured-noise baseline used to check false positives; it has no special params. “Circles” and “Moons” are intentionally non-convex shapes that break spherical-cluster assumptions; their params (damping, preference, quantile, n_clusters) reflect the need to tune affinity/propagation and bandwidth-based algorithms (damping/preference for affinity propagation, quantile for bandwidth estimation used by MeanShift or similar, and forcing n_clusters=2 to express known ground-truth) so the algorithm can capture ring or crescent shapes rather than incorrectly splitting or merging them.

A few operational notes tied to the market-pattern goal: these synthetic scenarios map to common regimes you might see in financial time-series feature space — tight regimes, regime shifts with differing variances, correlated (stretched) factor moves, noisy/unstructured periods, and non-linear relationships or cyclical patterns. Testing clustering behavior across these shapes helps choose algorithms and hyperparameters that are robust before running on real market data. Also, because many of the params are distance- or density-sensitive, you should always ensure consistent feature scaling and consider automating bandwidth/neighborhood selection (or cross-validation) for production use; hard-coded params are useful for demos and reproducibility but should be replaced by principled selection methods or validation when moving to live market discovery.

Plot Results from the Clustering Algorithm

fig, axes = plt.subplots(figsize=(15, 15),

ncols=5,

nrows=len(datasets),

sharey=True,

sharex=True)

plt.setp(axes, xticks=[], yticks=[], xlim=(-2.5, 2.5), ylim=(-2.5, 2.5))

for d, (dataset_label, dataset, algo_params) in enumerate(datasets):

params = default_params.copy()

params.update(algo_params)

X, y = dataset

X = StandardScaler().fit_transform(X)

# connectivity matrix for structured Ward

connectivity = kneighbors_graph(X, n_neighbors=params[’n_neighbors’],

include_self=False)

connectivity = 0.5 * (connectivity + connectivity.T)

kmeans = KMeans(n_clusters=params[’n_clusters’])

spectral = SpectralClustering(n_clusters=params[’n_clusters’],

eigen_solver=’arpack’,

affinity=’nearest_neighbors’)

dbscan = DBSCAN(eps=params[’eps’])

average_linkage = AgglomerativeClustering(linkage=”average”,

affinity=”cityblock”,

n_clusters=params[’n_clusters’],

connectivity=connectivity)

gmm = GaussianMixture(n_components=params[’n_clusters’],

covariance_type=’full’)

clustering_algorithms = ((’KMeans’, kmeans),

(’SpectralClustering’, spectral),

(’AgglomerativeClustering’, average_linkage),

(’DBSCAN’, dbscan),

(’GaussianMixture’, gmm))

for a, (name, algorithm) in enumerate(clustering_algorithms):

if name == ‘GaussianMixture’:

algorithm.fit(X)

y_pred = algorithm.predict(X)

else:

y_pred = algorithm.fit_predict(X)

axes[d, a].scatter(X[:, 0],

X[:, 1],

s=5,

c=y_pred,

cmap=cmap)

if d == 0:

axes[d, a].set_title(name, size=14)

if a == 0:

axes[d, a].set_ylabel(dataset_label, size=12)

if y is None:

y = [.5] * n_samples

mi = adjusted_mutual_info_score(labels_pred=y_pred,

labels_true=y)

axes[d, a].text(0.85, 0.91,

f’MI: {mi:.2f}’,

transform=axes[d, a].transAxes,

fontsize=12)

axes[d, a].axes.get_xaxis().set_visible(False)

sns.despine()

fig.tight_layout()The code is building a small evaluation and visualization pipeline that runs several unsupervised clustering algorithms over multiple datasets so you can visually and quantitatively compare how each method discovers market patterns. At the top level it creates a grid of subplots with rows corresponding to datasets and columns to clustering algorithms, and it forces a common visual frame (shared x/y axes, fixed axis limits and removed tick marks) so differences in cluster geometry are easier to compare at a glance.

For each dataset the first step is to copy and merge algorithm parameters so each dataset can override defaults. The feature matrix X is immediately standardized with StandardScaler — this is important because almost all of the clustering methods here are distance- or covariance-based, so scaling prevents features with larger numeric ranges (for example volatility vs return magnitude) from dominating the distance calculations and producing misleading cluster assignments.

Next the code builds a k-nearest-neighbors connectivity graph from X and symmetrizes it with 0.5*(A + A.T). Symmetrization produces an undirected adjacency matrix; this is necessary for algorithms that accept a connectivity constraint (here AgglomerativeClustering) and for neighborhood-based spectral methods. The connectivity encodes local structure — which points are “neighbors” in feature space — and is used to encourage agglomerative clustering to merge along locally coherent groups rather than globally-linking far-away points.

The script instantiates five clustering approaches with different inductive biases: KMeans (centroid-based, spherical clusters), SpectralClustering (graph/eigenvector-based, using nearest-neighbors affinity and an eigensolver), AgglomerativeClustering with average linkage and a cityblock affinity constrained by the precomputed connectivity (hierarchical, locality-preserving merges), DBSCAN (density-based, controlled by eps so it can find arbitrarily-shaped clusters and mark noise), and a GaussianMixture model (probabilistic, full-covariance elliptical clusters). Each algorithm’s parameters are taken from the merged params so you can tune neighbors, eps, and n_clusters per dataset. Note that GaussianMixture is called with fit() followed by predict() because its API returns responsibilities and then requires a separate predict step; the other estimators expose fit_predict() for convenience.

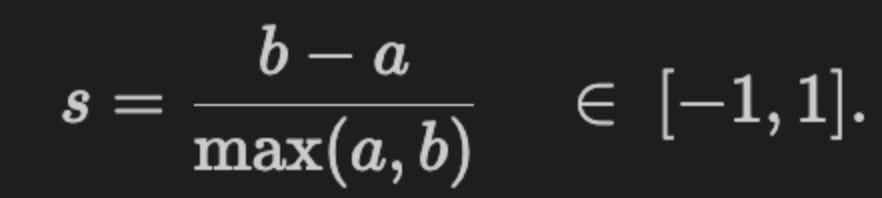

Inside the inner loop each algorithm is fit and the predicted labels are used to color a scatter plot of the first two scaled dimensions. Presenting the same two axes across methods makes it easy to see how centroid, graph, hierarchical, density, and model-based methods partition the same market feature space differently — important when you are searching for recurring market patterns that may be linear, manifold-like, density-driven, or elliptical. Titles and dataset labels are added only where relevant to keep the grid readable.

To provide a quantitative measure the code computes adjusted_mutual_info_score (AMI) between predicted labels and a supplied y. AMI is a good choice for comparing clusterings because it is permutation-invariant (cluster label indices do not need to match) and it’s adjusted for chance, so it is more meaningful than raw overlap. If y is None the code substitutes a constant dummy label vector to avoid errors, but that effectively yields a meaningless MI — in practice you would want to either supply a ground-truth segmentation or skip the score when none exists. The MI value is annotated on each subplot in axis-relative coordinates so you can quickly scan algorithm performance across datasets.

Finally, the plot aesthetics are tightened (sns.despine and tight_layout) so the grid is compact and visually comparable. Overall, this block is designed to let you iterate over different datasets and parameterizations and immediately see how different unsupervised algorithms expose different structures in market data — helping you choose methods that reveal robust, actionable market patterns for downstream clustering or regime-detection tasks.

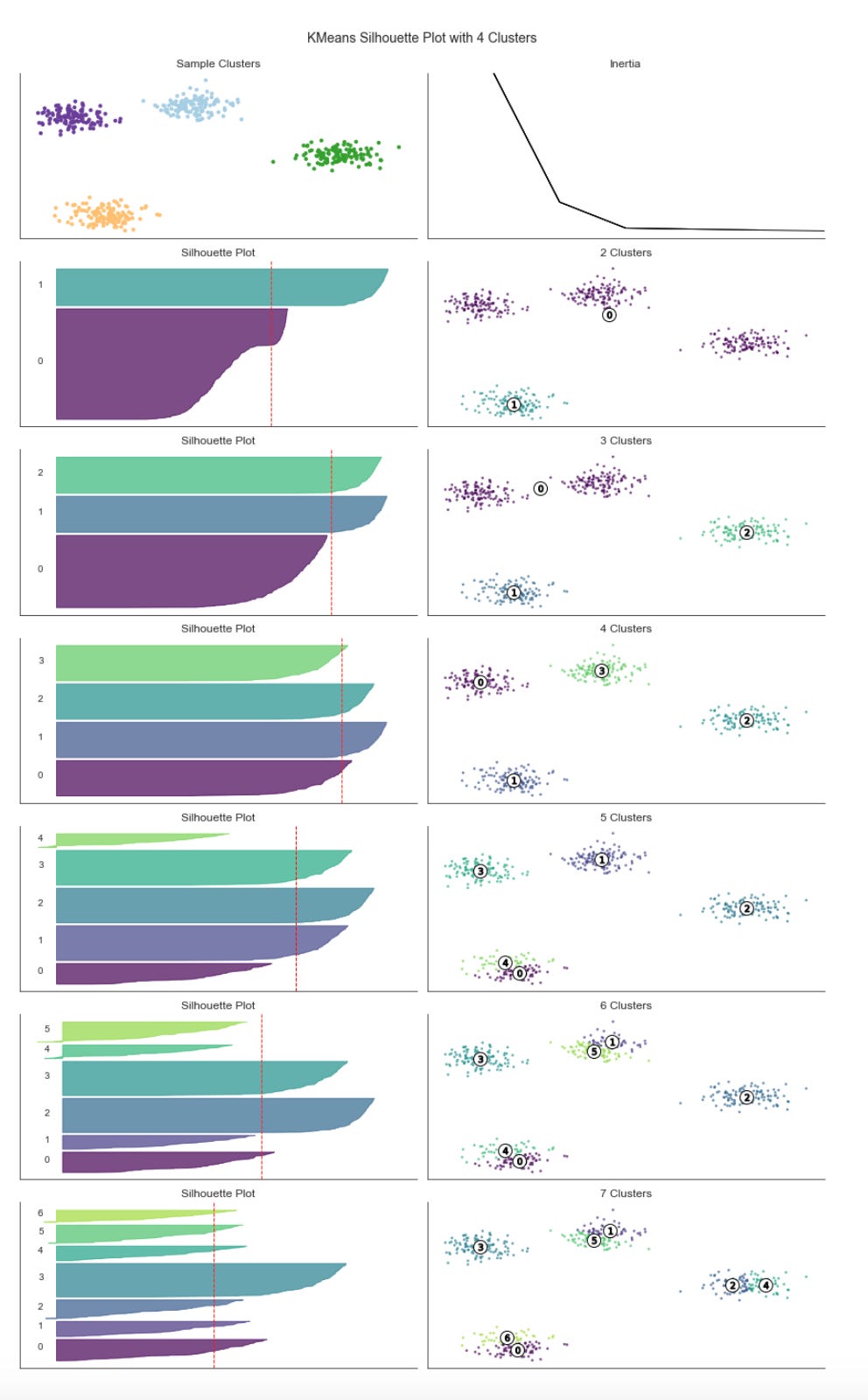

k-Means Clustering — Implementation

k-Means is the best-known clustering algorithm, originally proposed by Stuart Lloyd at Bell Labs in 1957.

The algorithm identifies K centroids and assigns each data point to exactly one cluster, with the objective of minimizing the within-cluster variance (also called inertia). It typically uses Euclidean distance, though other distance metrics can be applied. k-Means implicitly assumes clusters are spherical and of similar size and does not account for covariance among features.

The clustering problem is NP-hard: there are K^N possible ways to partition N observations into K clusters. The standard iterative k-Means algorithm converges to a local optimum for a given K and proceeds as follows:

1. Initialize: randomly select K cluster centers and assign each point to the nearest centroid.

2. Repeat until convergence:

a. For each cluster, recompute the centroid as the mean of its members.

b. Reassign each observation to the closest centroid.

3. Convergence criterion: assignments (or the within-cluster variance) no longer change.

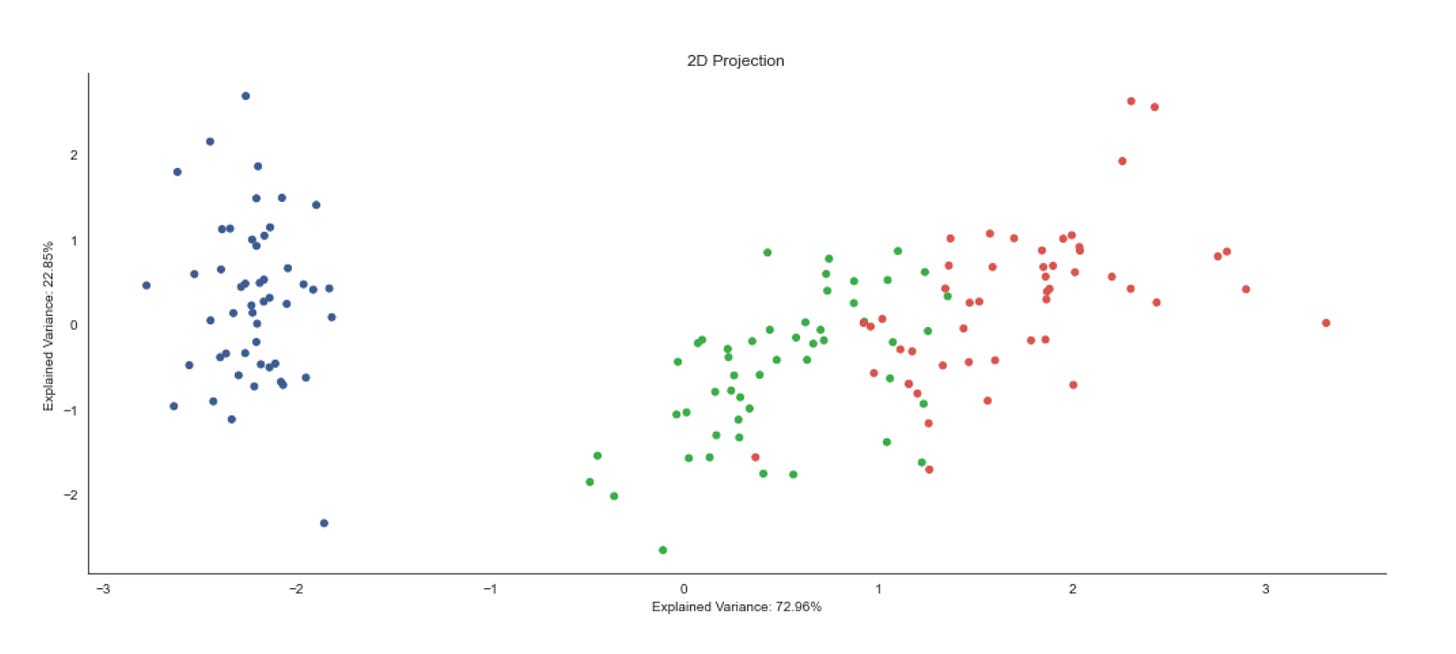

2D Cluster Demonstration

def sample_clusters(n_points=500,

n_dimensions=2,

n_clusters=5,

cluster_std=1):

return make_blobs(n_samples=n_points,

n_features=n_dimensions,

centers=n_clusters,

cluster_std=cluster_std,

random_state=42)This small helper function is a deterministic data generator intended to produce a controlled, synthetic dataset of clustered points that you can use as a playground for unsupervised learning tasks like cluster discovery and validation. Conceptually, the function delegates to sklearn.datasets.make_blobs to synthesize n_points observations in an n_dimensions feature space, where those observations are drawn from a mixture of n_clusters isotropic Gaussian blobs. The generated output is the usual (X, y) pair: X is a floating-point feature matrix you can feed to clustering algorithms, and y are the ground-truth cluster labels you can use for evaluation and debugging.

Walking through the data flow: the caller specifies how many samples to create, how many numeric features each sample should have, how many latent clusters to emulate, and how much intra-cluster dispersion to inject via cluster_std. make_blobs creates cluster centers (by default randomly placed but reproducible here) and then samples points around each center according to a spherical Gaussian with the specified standard deviation. Because we pass random_state=42, the same centers and draws are produced every time, which makes experiments and visual comparisons repeatable.

Why these choices matter: n_points controls statistical stability and realistic sample sizes for downstream algorithms; n_dimensions lets you mimic feature complexity — low-dimensional (2D) output is convenient for visualization and intuition, while higher dimensions are useful to stress-test algorithms and pipelines. n_clusters encodes the expected number of latent market regimes or pattern types you want to simulate; cluster_std controls separability and noise level — small std produces well-separated, easy-to-find regimes, while larger stds create overlap and ambiguity like real-world market noise, which is where clustering robustness matters. The fixed random_state is deliberate so you can iterate on preprocessing, algorithms and hyperparameters without the confound of data variance.

In the context of unsupervised learning for market pattern discovery, this generator is primarily a diagnostic and development tool: it lets you validate that your clustering pipeline (feature scaling, dimensionality reduction, model selection and evaluation metrics) behaves sensibly under known ground truth before you apply it to noisy, nonstationary market data. Use the returned labels to compute external metrics (ARI, AMI) and to compare how different clustering algorithms or distance metrics recover the planted structure. Also use parameter sweeps (vary cluster_std, n_clusters, dimensionality) to simulate different market regimes and stress-test sensitivity to overlap and high-dimensionality.

Be aware of limitations: make_blobs produces simple, isotropic Gaussian clusters, so it does not capture many realistic market data properties such as skewness, heavy tails, time dependence, heteroskedasticity, or complex non-linear cluster shapes. For those, you’ll need more sophisticated simulation (e.g., mixtures with anisotropic covariances, temporal dynamics, or synthetic series with regime switching). Finally, because many clustering methods are scale-sensitive, remember to include appropriate scaling or normalization after generating X when you’re evaluating algorithms.

data, labels = sample_clusters(n_points=250,

n_dimensions=2,

n_clusters=3,

cluster_std=3)This single call is creating a small synthetic dataset that mimics clustered market behavior so we can develop and validate unsupervised clustering workflows. Internally the helper sample_clusters will choose (explicitly or implicitly) a set of cluster centers in a 2‑D feature space and then draw points around those centers; the result is a matrix of observations (data) and a corresponding vector of ground‑truth cluster assignments (labels). The function parameters control the dataset shape and difficulty: n_points=250 determines the total number of sample observations (so you’ll roughly get 250 / n_clusters points per cluster if the generator distributes points evenly), n_dimensions=2 makes the samples two‑dimensional so they’re easy to visualize and debug, n_clusters=3 forces the generator to create three distinct latent groups, and cluster_std=3 sets the Gaussian standard deviation used to scatter points around each center.

Why we do this: synthetic clustered data gives us a controlled sandbox to test clustering algorithms and experiment with preprocessing and evaluation strategies before moving to noisy market data. The cluster_std parameter is especially important because it governs the signal‑to‑noise ratio — a small std produces tight, well‑separated groups that are easy to recover, while a larger std (like 3 here) increases intra‑cluster variance and overlap, which simulates realistic variability in market patterns and tests robustness of methods (k‑means, GMM, DBSCAN, spectral clustering, etc.). Choosing n_dimensions=2 is a deliberate tradeoff: it simplifies inspection and plotting so we can quickly validate whether an algorithm is capturing the intended structure; raising dimensions later lets us exercise behavior under the “curse of dimensionality.”

How the outputs are used in an unsupervised workflow: data feeds the clustering pipeline (possibly after scaling, PCA/UMAP, or feature engineering), while labels are not used to train unsupervised models but retained as ground truth for offline evaluation and parameter tuning — e.g., computing ARI/AMI/Fowlkes–Mallows to compare recovered clusters to true assignments or to run sensitivity analyses on preprocessing choices. Practically, if you care about reproducibility or consistent experiments with different cluster spreads, ensure the generator’s random seed is controlled; also consider whether the generator uses equal cluster sizes and per‑cluster stds or supports heterogeneity if you need more realistic market scenarios.

In short, this line produces a controlled, two‑dimensional, three‑cluster synthetic dataset with moderate spread, giving you both the inputs to run clustering and the labels to quantitatively evaluate algorithm behavior under the kind of intra‑cluster variability you might expect when discovering market patterns.

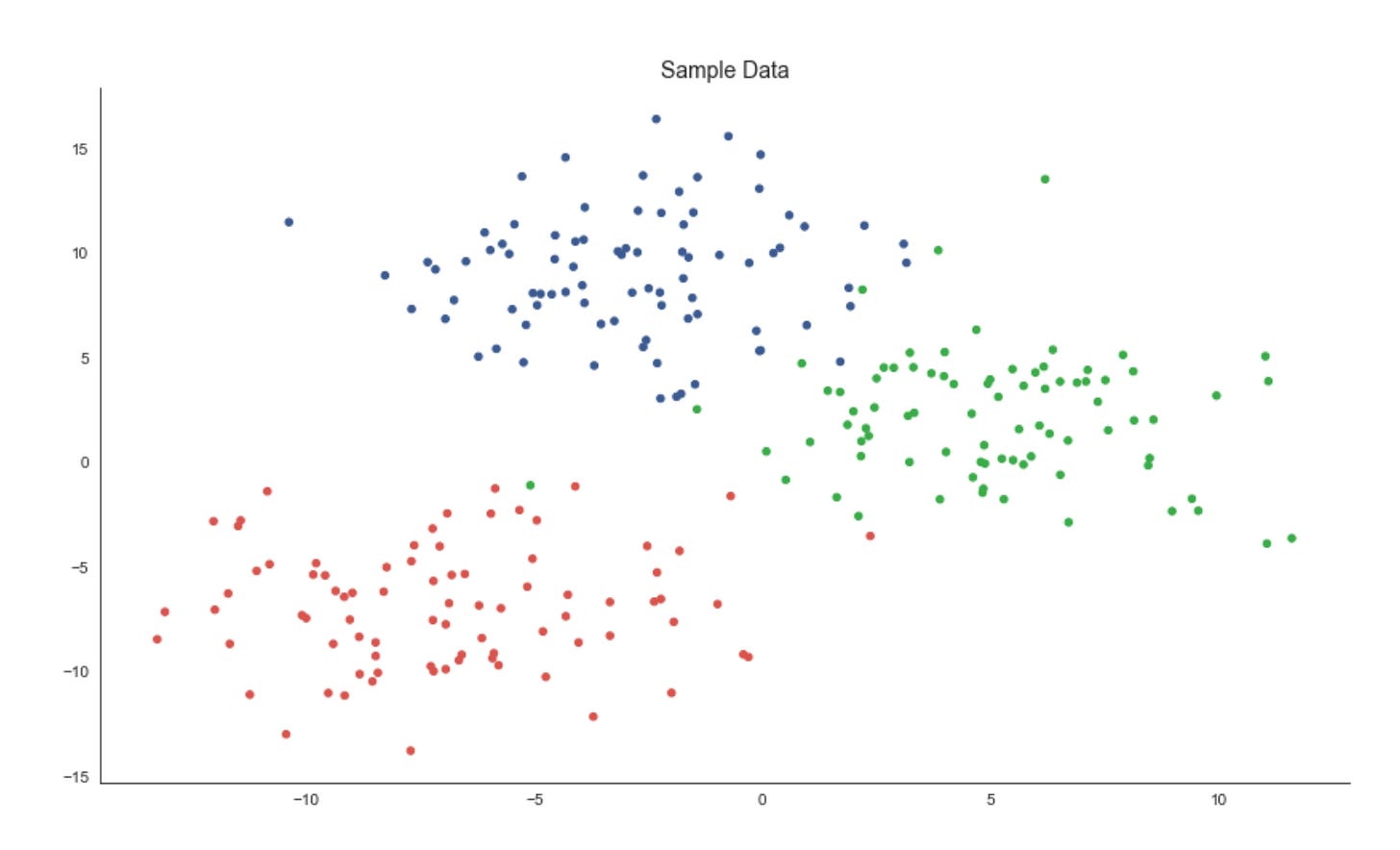

x, y = data.T

plt.figure(figsize=(14, 8))

plt.scatter(x, y, c=labels, s=20, cmap=cmap)

plt.title(’Sample Data’, fontsize=14)

sns.despine();The first line unpacks the two coordinate dimensions from the input array into variables x and y. Practically, this treats each row (or column, depending on how data is shaped) as a separate feature axis so we can plot a two‑dimensional view of the dataset — an important step in unsupervised workflows because a 2D projection gives immediate visual intuition about structure, separability and outliers before deeper quantitative evaluation.

Next, we create a plotting canvas with a deliberately large figure size to ensure points and color differences are readable when you have many samples. The scatter plot then places each sample at its (x, y) coordinates and uses the labels array to assign colors via the colormap. In the context of market pattern discovery, those labels usually represent cluster assignments or some continuous score derived from an unsupervised model; coloring by labels lets you visually validate whether the algorithm has found coherent groups, whether clusters are compact or elongated, and where clusters overlap or produce ambiguous boundaries. The point size (s=20) is chosen to balance density and legibility — small enough to avoid excessive occlusion but large enough to perceive local structure — while the chosen cmap controls how distinct category or value differences appear; if labels are categorical, a discrete/qualitative colormap is preferable to avoid implying an ordering that doesn’t exist.

Finally, we add a concise title for readability and call sns.despine() to remove the top and right axes lines so the plot reads cleaner and focuses attention on the data geometry. The overall purpose of this block is exploratory validation: by visually inspecting the spatial arrangement of labeled points you can decide whether to change clustering hyperparameters, re‑engineer features (e.g., add volatility or seasonality signals), apply a different distance metric, or proceed with downstream analysis such as cluster profiling, anomaly investigation, or regime‑based strategy development.

K-means implementation

Assign Points to the Nearest Centroid

def assign_points(centroids, data):

dist = cdist(data, centroids) # all pairwise distances

assignments = np.argmin(dist, axis=1) # centroid with min distance

return assignmentsThis small function implements the assignment step of a prototype-based clustering loop (think k-means style). It takes a set of current centroids and all data points, computes the pairwise distances from every data point to every centroid, and then assigns each point to the centroid with the minimum distance. Concretely, the distance matrix has one row per data point and one column per centroid; argmin across columns yields a length-n array of integer indices that map each point to its nearest centroid. Those indices are the fundamental labels used by the algorithm to recompute centroids and to evaluate convergence.

Why we do this: the assignment transforms continuous feature observations into discrete cluster memberships so we can summarize similar market behaviors. Choosing the nearest centroid creates a Voronoi partition of feature space — each centroid represents the prototype pattern for its cell, and data points belonging to that cell are considered instances of that pattern. This step is the “E-step” in expectation–maximization-style clustering or the assignment phase in k-means; without it you cannot compute the next centroid locations or the cluster-level statistics needed for pattern discovery.

Important assumptions and shape/metric expectations: this code assumes data and centroids are 2-D arrays with the same feature dimensionality (n×d and k×d). cdist (from SciPy) is typically Euclidean by default, so the notion of “nearest” is Euclidean distance unless you change the metric. That choice matters a lot for market data: raw price levels, returns, volatility, autocorrelation features, or normalized shape descriptors each interact differently with Euclidean geometry. Because Euclidean distance is sensitive to scale, you should normalize or standardize features (or choose an alternative metric) before calling this function to prevent some features from dominating assignments.

Performance and scaling considerations: computing the full n×k distance matrix is O(n·k·d) in time and O(n·k) in memory, which is fine for moderate datasets but can be a bottleneck for very large tick-level or multi-instrument datasets. If you anticipate large n or k, consider batching/chunking the data, using spatial indexes (KD-tree, BallTree) or approximate nearest-neighbor methods, or using more memory-efficient pairwise argmin utilities (scikit-learn has optimized functions) to reduce both time and memory pressure.

Operational edge cases and robustness: ties in distance are resolved by argmin’s deterministic index ordering (first minimum wins), but for noisy market data you may see many near-ties; consider adding tie-breaking logic or deterministic perturbation if that matters. Watch out for NaNs in inputs (will propagate into distances) and for empty clusters after centroid recomputation — if a centroid loses all points you’ll need a reinitialization strategy (reseed from data, split largest cluster, etc.). Also ensure centroids are updated with the same feature scaling used here to keep assignments meaningful.

In the larger context of unsupervised learning for market pattern discovery, this function is the mechanism that groups observations around prototype behaviors. Repeating assignment and centroid-update steps produces compact cluster prototypes that summarize recurring market motifs (e.g., specific intraday shapes, regime signatures, or volatility patterns). Getting assignments correct and meaningful — by choosing appropriate features, scaling, and distance metrics — is therefore critical to discovering actionable, interpretable clusters of market behavior.

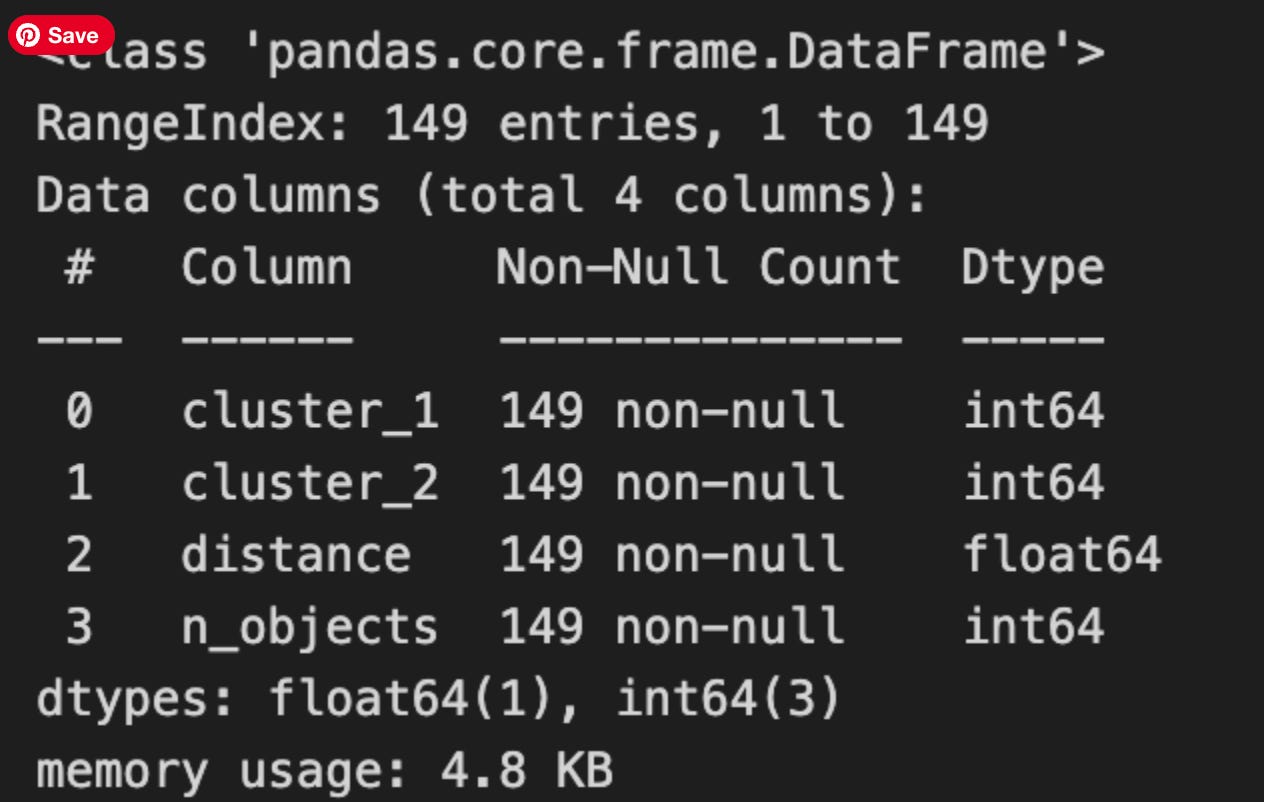

Adjust centroids to better represent clusters

def optimize_centroids(data, assignments):

data_combined = np.column_stack((assignments.reshape(-1, 1), data))

centroids = pd.DataFrame(data=data_combined).groupby(0).mean()

return centroids.valuesThis small function implements the “centroid update” step you see in k-means–style clustering: given a matrix of feature vectors and an array of integer cluster assignments, it returns the mean feature vector for each cluster (i.e., the centroids). Practically, it first ensures assignments are a column vector and concatenates that column with the feature matrix so each row is [label, features]. Wrapping that combined array in a pandas DataFrame lets the code group rows by the label column (column 0) and compute the column-wise mean for each group; the resulting DataFrame rows are the centroids and .values converts them back to a NumPy array for downstream numeric use.

Why do we compute means here? The arithmetic mean minimizes squared error within each cluster, so replacing cluster members with their mean reduces within-cluster variance and produces a prototypical pattern for that cluster. In an unsupervised market-pattern workflow those centroids are the canonical patterns we use for interpretation, anomaly detection, or to reassign time series segments in the next algorithm iteration.

A few operational details to keep in mind. The function returns an array of shape (k, d) where k is the number of distinct labels present in assignments and d is the number of feature columns; however, k equals the number of labels actually present, not necessarily the nominal number of clusters you expected. Pandas.groupby will produce rows only for labels that appear, and its groups are ordered by the group key (sorted unless you pass sort=False). That means if some cluster indices have no members (empty clusters) they simply won’t appear in the output — downstream code that relies on a fixed mapping from cluster index to centroid must either reindex the result or otherwise handle missing labels. Also note NaNs in the input features will propagate into the means unless you pre-clean or specify skipna behavior; and repeated conversions to DataFrame may be suboptimal for very large tick-level market datasets.

If you need greater performance or explicit handling of empty clusters, consider an alternative numeric approach (e.g., per-label sums and counts via np.bincount to compute means and to detect zero-count clusters) or keep a persistent centroid array and fill empty-cluster slots with prior centroids. In short: this function succinctly implements centroid recomputation via group-mean aggregation, which is the core update step for discovering and refining market pattern clusters, but be deliberate about label continuity, missing clusters, NaN handling, and performance for large-scale market data.

Compute Distances from Points to Centroids

def distance_to_center(centroids, data, assignments):

distance = 0

for c, centroid in enumerate(centroids):

assigned_points = data[assignments == c, :]

distance += np.sum(cdist(assigned_points, centroid.reshape(-1, 2)))

return distanceThis small function computes the total within-cluster distance between data points and their assigned centroids, producing a single scalar that quantifies cluster compactness. It walks through each centroid index, selects all data rows whose cluster label equals that index, computes the pairwise Euclidean distances between those assigned rows and the centroid representation, and accumulates the sum of those distances. The final returned value is the aggregate distance across all clusters and therefore serves as an objective or diagnostic number you can minimize or monitor while fitting a clustering model.

Operationally, the key steps are: for each centroid c, the line assigned_points = data[assignments == c, :] filters the dataset down to only the observations currently assigned to cluster c. The code then calls scipy.spatial.distance.cdist to compute distances between these assigned observations and the centroid. Because cdist expects 2-D arrays (rows = observations, columns = features), the centroid is reshaped with centroid.reshape(-1, 2) before calling cdist. That reshape implies a specific data layout: each centroid is stored as a flat array that must be interpreted as a sequence of 2-dimensional feature pairs (for example, time steps each with [price, volume]). cdist returns a matrix of pairwise distances and np.sum aggregates them into a scalar; that scalar is added to the running total.

Why this is done: summing distances to centroids gives a simple, interpretable measure of how well centroids represent their assigned points — lower totals mean tighter clusters. In the context of unsupervised market pattern discovery, this function is evaluating how closely each market pattern prototype (the centroid) matches the actual market segments assigned to it. Using Euclidean distances (cdist’s default) is computationally cheap and effective when features are aligned and comparable (e.g., normalized price-volume pairs across timesteps). The centroid reshape to (-1, 2) enforces the temporal/paired structure of market observations so distances compare corresponding feature pairs.

A few practical notes and assumptions to be aware of: assigned_points must have the same per-row dimensionality as the reshaped centroid — otherwise cdist will error or produce unintended results. If a centroid has no assigned points, the slice yields an empty array and the summed contribution is zero (so the function tolerates empty clusters). Also, this function sums raw Euclidean distances rather than squared distances; traditional k-means optimizes the sum of squared distances, so if you are using this as an optimization objective you should align the distance form with the algorithm. Finally, for performance and clarity you might preprocess centroids into the correct 2-D shape once (avoiding repeated reshape operations) and consider vectorizing the accumulation (or using squared distances) if you need to scale this to large collections of time-series market patterns.

Dynamic Cluster Plotting

def plot_clusters(x, y, labels,

centroids, assignments, distance,

iteration, step, ax, delay=2):

ax.clear()

ax.scatter(x, y, c=labels, s=20, cmap=cmap)

# plot cluster centers

centroid_x, centroid_y = centroids.T

ax.scatter(*centroids.T, marker=’o’,

c=’w’, s=200, cmap=cmap,

edgecolor=’k’, zorder=9)

for label, c in enumerate(centroids):

ax.scatter(c[0], c[1],

marker=f’${label}$’,

s=50,

edgecolor=’k’,

zorder=10)

# plot links to cluster centers

for i, label in enumerate(assignments):

ax.plot([x[i], centroid_x[label]],

[y[i], centroid_y[label]],

ls=’--’,

color=’black’,

lw=0.5)

sns.despine()

title = f’Iteration: {iteration} | {step} | Inertia: {distance:,.2f}’

ax.set_title(title, fontsize=14)

ax.axes.get_xaxis().set_visible(False)

ax.axes.get_yaxis().set_visible(False)

display.display(plt.gcf())

display.clear_output(wait=True)

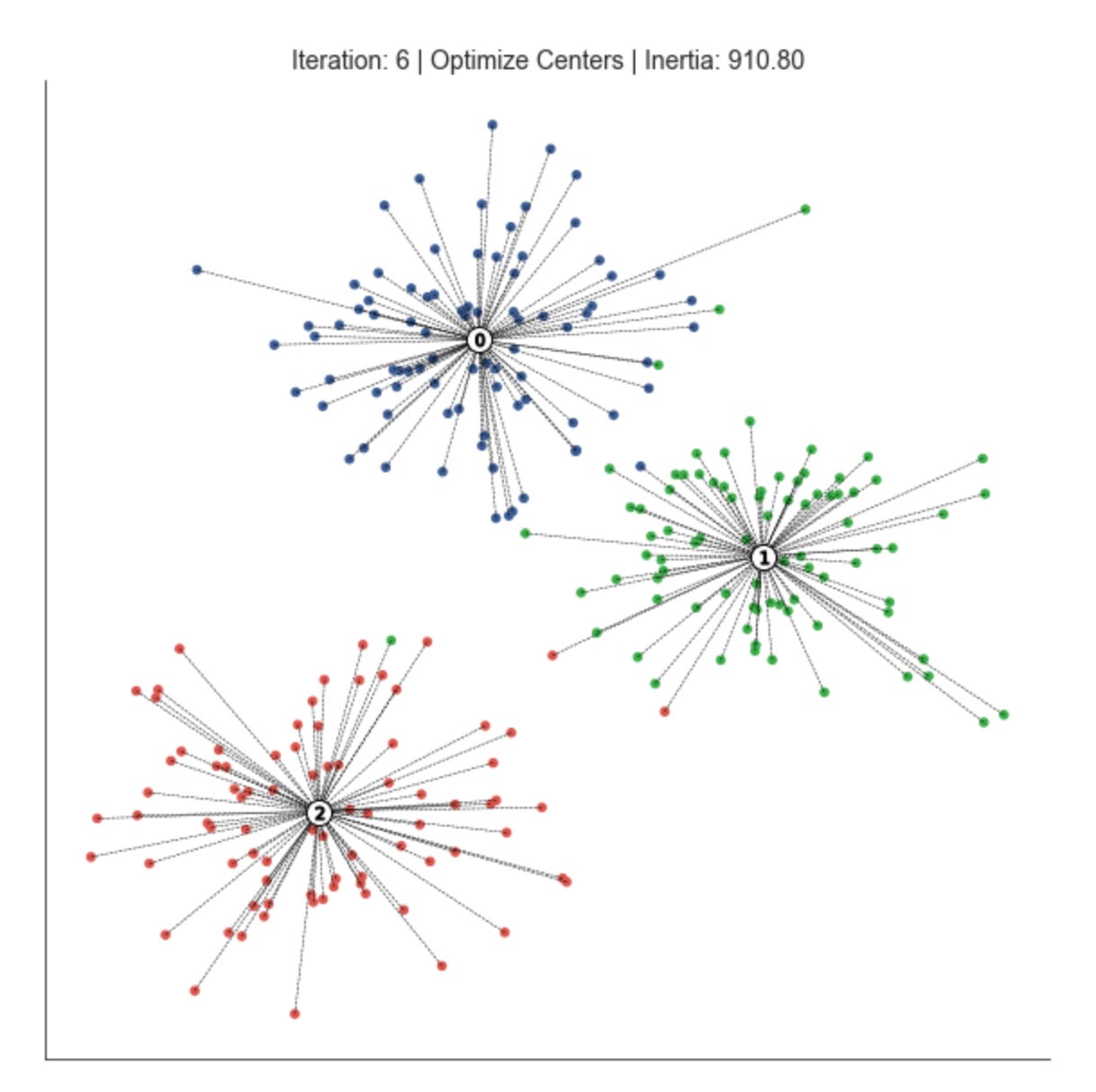

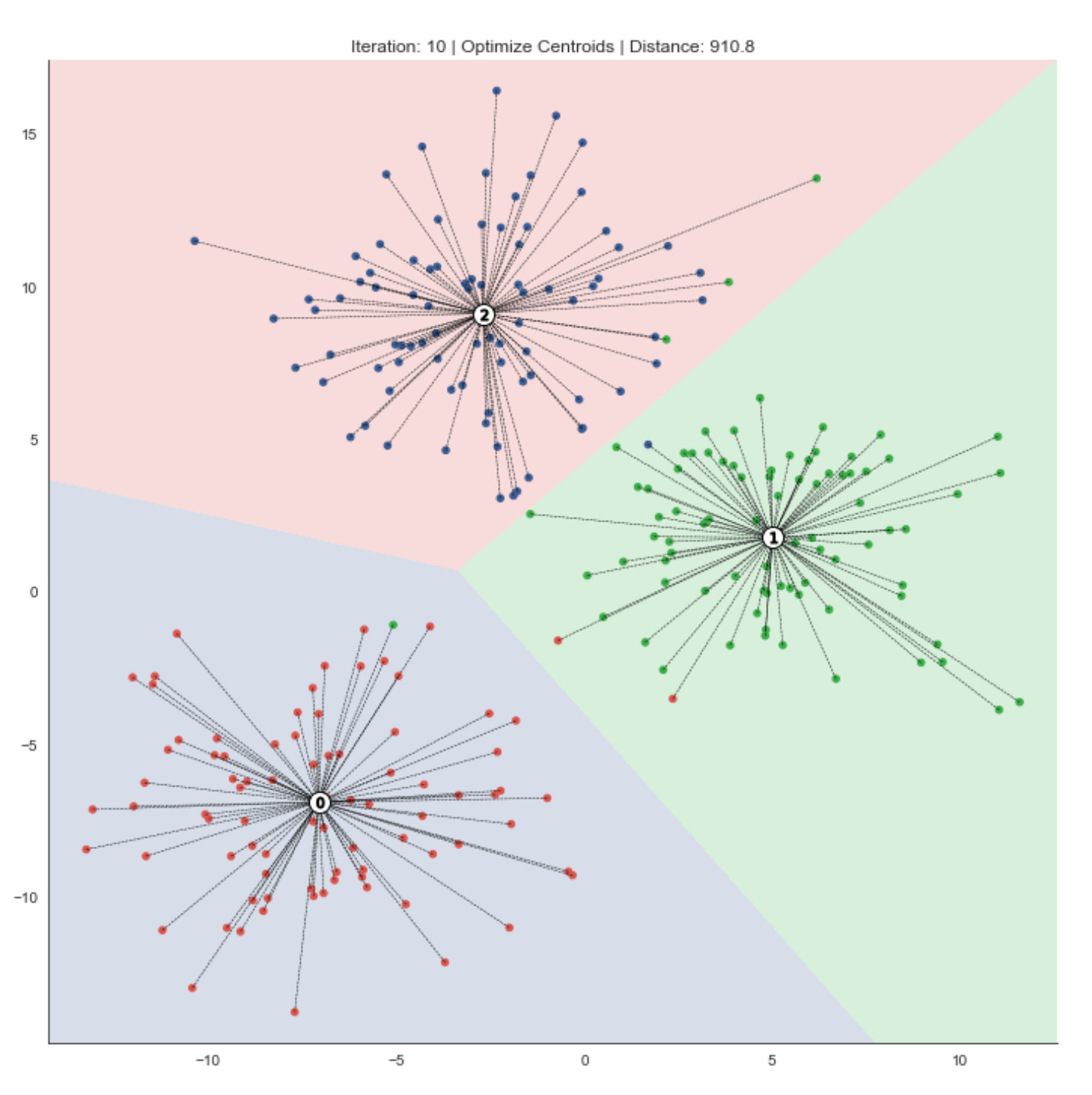

sleep(delay)This function is purely a visualization routine that animates one step of a clustering algorithm so you can watch how market data points are being grouped and how the cluster centers evolve. Conceptually, the inputs are the point coordinates (x, y), a color label per point for aesthetic grouping (labels), the current centroid locations, the current assignment of each point to a centroid (assignments), a scalar “distance” measure (inertia), and metadata about iteration and step. The routine’s job is to lay these pieces out on an axes object so you can judge clustering quality and behavior as the algorithm runs over iterations.

First the routine draws the dataset as a scatter, coloring points by the provided labels. Coloring by label (rather than raw coordinates) is important for human pattern recognition: it lets you immediately see which points are considered part of the same cluster and whether those groups align with visually coherent market regimes or technical patterns. The centroids are then drawn on top with a larger, high-contrast marker (white fill with a black edge) and placed at a higher z-order so they remain visible even when many points overlap them. This visual hierarchy (points below, centers above) makes centroid movement and convergence easy to follow during iterations.

To make cluster identities explicit, the code then overlays a small, labeled marker at each centroid showing the cluster index. Displaying the index on the centroid is useful when you want to trace how a particular cluster ID moves across iterations or to correlate that ID with downstream analytics (e.g., feature distributions or trading signals derived from that cluster). The black-edged, numbered markers reduce ambiguity that can arise when colors are similar or when cluster centroids cross paths.

Next, the function draws dashed lines from every data point to the centroid it is currently assigned to. That step is particularly informative for debugging and for understanding algorithmic decisions: long lines highlight poorly fitting points or potential outliers, large cumulative line lengths reflect higher inertia, and changes in the pattern of lines from one iteration to the next reveal whether points are being reassigned or if centroids are stabilizing. The distance value passed into the function is shown in the title; semantically this should be the clustering inertia or within-cluster sum-of-squares, so pairing it with the assignment links gives you both a global numeric objective and a local, visual explanation for that objective.

Finally, the routine polishes the view for an animation-style presentation: it removes axis ticks/frames (sns.despine and hiding axes) so you focus on the clusters, sets a descriptive title that includes iteration, step, and inertia so you can track progress, and uses display/clear_output combined with sleep to render the frame and pause briefly. That pattern is designed for interactive environments (Jupyter) and intentionally slows the loop so you can inspect transitions between algorithmic steps (for example, “assignment” vs “update” phases). A couple of practical notes: drawing a line per point is informative but can become costly for large datasets — consider sampling points or throttling frame frequency for production-scale visual debugging. Also ensure the passed-in distance is the same objective the algorithm optimizes (so the title accurately reflects convergence), because that metric is the primary numeric signal you’ll use alongside the visual cues to decide whether the clustering is discovering meaningful market patterns.

Run the K-Means Experiment

The following figures highlight how the resulting centroids partition the feature space into regions — Voronoi cells — that delineate the clusters.

k-means requires continuous features or categorical variables encoded with one-hot encoding. Because the algorithm relies on distance metrics that are sensitive to scale, features should be standardized so they contribute equally.

The result is optimal for the chosen initialization; however, different starting positions can produce different outcomes. Therefore, we run the clustering procedure multiple times from different initial values and select the solution that minimizes within-cluster variance.

n_clusters = 3

data, labels = sample_clusters(n_points=250,

n_dimensions=2,

n_clusters=n_clusters,

cluster_std=3)

x, y = data.TThis short block is setting up a controlled synthetic dataset that we’ll use as a playground for unsupervised market-pattern discovery and clustering experiments. We first decide on the experiment parameters: n_clusters = 3 declares that we want three underlying groups (this mirrors the hypothesis that there are three repeating market regimes or pattern families to discover). The call to sample_clusters(…) then synthesizes a 2‑dimensional point cloud of 250 observations composed of those three clusters; cluster_std=3 controls the Gaussian dispersion of each cluster and therefore how much overlap and noise exists between groups.

The sensible choices here serve specific purposes. Using n_dimensions=2 keeps the feature space low-dimensional so we can visualize results directly (useful during development and debugging) while still having nontrivial structure. The moderate cluster_std intentionally prevents perfectly separable clusters: it forces clustering algorithms to demonstrate robustness to noise and boundary ambiguity, which is important because real market patterns are noisy and overlapping. The returned labels are the ground‑truth cluster assignments produced by the sampler and are useful only for evaluation (e.g., computing ARI, NMI, or cluster purity); in a true unsupervised pipeline you would feed only the data into the clustering model and use labels solely to measure success.

Concretely, sample_clusters produces an array data with shape (250, 2) — each row is an observation in 2D — and a labels array of length 250 with the cluster index for each point. The final line x, y = data.T transposes and unpacks the two coordinate columns into vectors of length 250 so they’re convenient for visualization or for any algorithm that expects separate feature arrays. Overall, this block establishes a repeatable, interpretable testbed: a modest-sized, two-dimensional, three‑cluster dataset with controlled noise, which we can use to develop, compare, and validate unsupervised clustering approaches intended to surface recurring market patterns.

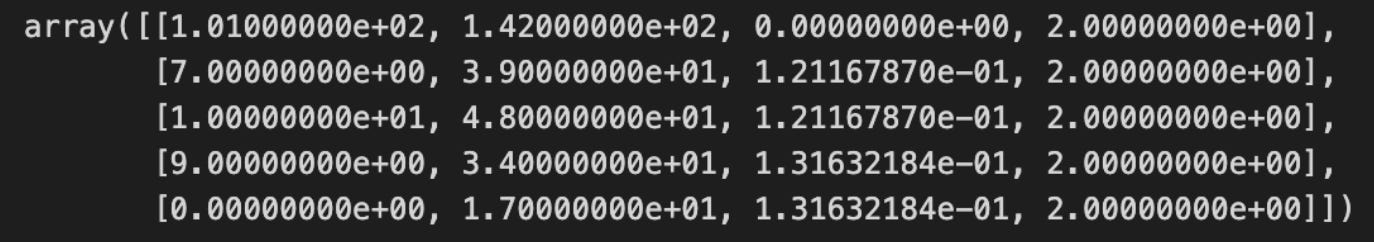

x_init = uniform(x.min(), x.max(), size=n_clusters)

y_init = uniform(y.min(), y.max(), size=n_clusters)

centroids = np.column_stack((x_init, y_init))

distance = np.sum(np.min(cdist(data, centroids), axis=1))This short block is doing two related things for an unsupervised clustering step: it seeds a set of centroids in the 2D feature space and then computes a single-number measure of how well those centroids would “explain” the data right now. The ultimate goal — discovering recurring market patterns and grouping similar market states — depends heavily on where you start your centroids and on an objective you use to compare different starts, so both actions here are about initializing and evaluating a candidate clustering.

First, two arrays of random coordinates are drawn independently for each centroid: one from the observed range of the x feature and one from the observed range of the y feature. Sampling uniformly between x.min() and x.max() (and similarly for y) ensures every initial centroid lies within the bounding box of the historical market points rather than arbitrarily far away. That keeps the initial centroids relevant to the data distribution and avoids degenerate starts that would trivially yield very large distances. The two 1‑D arrays are then combined into an (n_clusters, 2) array of centroid coordinates; the column_stack step enforces the same 2‑column layout as the data so subsequent pairwise distance computations align by feature.

Next, the code measures how close every market observation is to its nearest centroid by computing all pairwise distances between data points and centroids (cdist returns an (n_samples, n_clusters) distance matrix) and taking the minimum distance per data point (np.min with axis=1). Summing those minima produces a single scalar that represents the total “within-cluster” distance for this particular initialization. Practically, this scalar functions as an immediate objective or score: lower values mean the centroids are, on average, nearer to data points and therefore form more compact clusters. In k‑means-style workflows this number is used to compare different initializations, drive iterative centroid updates, or select the best random seed; note that standard k‑means typically uses squared Euclidean distance (inertia), but the sum of Euclidean distances is a comparable compactness measure if you are consistent.

A couple of practical notes tied to the market-pattern goal: sampling coordinates independently into the bounding box can place centroids in low-density regions (outside the data convex hull) and lead to slower convergence or poor local minima, so it’s common to use smarter seeding (k-means++ or multiple random restarts) when searching for robust market patterns. Also ensure your distance metric matches your clustering objective (squared vs. linear distance) and that any downstream optimization is minimizing the same measure you compute here.

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 10))

iteration, tolerance, delta = 0, 1e-4, np.inf

while delta > tolerance:

assignments = assign_points(centroids, data)

plot_clusters(x, y, labels,

centroids,

assignments,

distance,

iteration,

step=’Assign Points’,

ax=ax)

centroids = optimize_centroids(data, assignments)

delta = distance - distance_to_center(centroids, data, assignments)

distance -= delta

plot_clusters(x, y, labels,

centroids,

assignments,

distance,

iteration,

step=’Optimize Centers’,

ax=ax)

iteration += 1This loop is implementing an iterative clustering procedure (essentially the k-means pattern) that alternates between assigning observations to the nearest prototype and recomputing those prototypes until the clustering stabilizes. We start with an iteration counter and a convergence tolerance; delta is seeded as infinite so the loop runs at least once. Each pass through the loop represents one refinement step in the search for stable market pattern prototypes (centroids) and the partitioning of the dataset into clusters that represent market regimes or recurring patterns.