Building a Stock Market Classifier: A Comparative Analysis of Baseline and LSTM Models

A comprehensive walkthrough of feature engineering, time-series cross-validation, and model evaluation with ROC curves

Download link at the end of article for source code!

Start by importing the libraries your script will use. Libraries are collections of ready-made code that save you from rewriting common tasks, like handling numbers, tables, plots, downloading stock quotes, or building neural networks. Doing this first makes your workspace ready and helps avoid missing-tool errors later.

Typical choices for an LSTM stock-forecasting project include numpy for number work, pandas for data tables (a DataFrame is just a smart table), matplotlib or seaborn for plotting, scikit-learn for things like scaling (scaling means putting numbers on the same range), a data source library like yfinance or pandas_datareader to fetch stock prices, and TensorFlow/Keras to build the LSTM model (an LSTM is a neural network good at learning from sequences like price histories). Importing these at the top keeps the code clear and tells anyone reading what tools the project relies on.

#Standard libraries

import pandas as pd

import seaborn as sns

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import time

# library for sampling

from scipy.stats import uniform

# libraries for Data Download

import datetime

from pandas_datareader import data as pdr

import fix_yahoo_finance as yf

# sklearn

from sklearn.pipeline import Pipeline

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

from sklearn.preprocessing import MinMaxScaler

from sklearn.model_selection import TimeSeriesSplit

from sklearn.model_selection import RandomizedSearchCV

from sklearn.model_selection import GridSearchCV

from sklearn import metrics

from sklearn.metrics import make_scorer

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn import linear_model

# Keras

import keras

from keras.models import Sequential

from keras.layers import LSTM

from keras.layers import Dense

from keras.layers import Dropout

from keras.wrappers.scikit_learn import KerasClassifierImagine we’re building a little factory that takes historical prices and tries to predict the next move; the opening lines import the tools the factory needs. Pandas supplies the spreadsheet-like workbench for time series, NumPy gives the fast number-crunching arrays, and seaborn plus matplotlib are the easel and paint for visualizing patterns; time helps us clock how long training takes. We bring in a sampler from SciPy so we can randomly try different hyperparameter values — like tasting random spice mixes when experimenting with a recipe.

To fetch data we load datetime for date handling and the pandas-datareader and Yahoo helper so the program can reach out and pull historical stock prices, like ordering ingredients from the market. For preparing inputs and evaluating models we assemble scikit-learn pieces: Pipeline to chain preprocessing and modeling steps into one assembly line; StandardScaler and MinMaxScaler to rescale features so they play nicely together — key concept: scaling makes different-valued features comparable by putting them on the same numerical footing. TimeSeriesSplit gives train/test folds that respect chronology — key concept: time-series cross-validation avoids peeking into the future by splitting along time.

We also import RandomizedSearchCV and GridSearchCV to search for good hyperparameters (randomized is like sampling at random, grid is exhaustive tasting), plus metrics and make_scorer to judge model quality, and train_test_split or simple baselines from linear_model to compare against.

Finally we bring in Keras: Sequential as a recipe card to stack layers, LSTM as the memory cell that learns temporal dependencies — key concept: an LSTM layer can remember information across time steps — Dense for final predictions, Dropout to reduce overfitting, and KerasClassifier to let the neural net plug into scikit-learn’s tools. Altogether, these imports prepare a pipeline to download data, scale it, tune and train an LSTM, and visualize how well our forecasts work in the larger stock-forecasting project.

We’ll group related code into small classes so the project stays tidy and easy to change later. A *Data class* reads your historical prices and turns them into sequences the LSTM can learn from; a sequence is a tiny timespan of past prices the model uses to predict the next price. This makes feeding data to the model consistent and lets you swap datasets without rewriting the training loop.

A Model class wraps the LSTM itself and its settings (how many layers, hidden size, etc.). Think of it as a neat box that knows how to take a sequence and return a prediction. Keeping model code here makes it simple to try different architectures or save and load weights.

A Trainer class runs the training loop: it handles batching, computes loss, steps the optimizer, and can implement early stopping (which stops training if validation loss stops improving). This separates “how we train” from “what we train,” so experiments are less error-prone and easier to reproduce.

Finally, add a Scaler class to normalize and inverse-transform prices (normalizing means scaling numbers to a small range so the model learns better). Normalization prevents large price values from dominating the learning and makes the model converge faster. Also include methods to save and load checkpoints so you can resume training or evaluate a saved model later.

# Define a callback class

# Resets the states after each epoch (after going through a full time series)

class ModelStateReset(keras.callbacks.Callback):

def on_epoch_end(self, epoch, logs={}):

self.model.reset_states()

reset=ModelStateReset()

# Different Approach

#class modLSTM(LSTM):

# def call(self, x, mask=None):

# if self.stateful:

# self.reset_states()

# return super(modLSTM, self).call(x, mask)Imagine you’re training a storyteller to predict stock moves, and you want a polite stagehand who steps in after each training pass (an epoch) to wipe the storyteller’s short-term memory so the next pass starts fresh. The class declaration creates that stagehand: class ModelStateReset(keras.callbacks.Callback) tells Keras “here’s a callback object that can hook into training events.” A callback is like an assistant that gets called at well-defined moments during training to perform side tasks. The on_epoch_end method is the specific cue the assistant listens for — it will run when an epoch finishes, receiving the epoch index and a logs dictionary (logs={} provides a default so the method signature always works). Inside that method self.model.reset_states() instructs the model to clear its recurrent hidden states; key concept: stateful RNNs keep their hidden states between batches to remember sequence context, and reset_states() erases that memory so successive epochs don’t incorrectly share state. The line reset = ModelStateReset() simply creates an instance of the assistant so you can pass it into model.fit(…, callbacks=[reset]) and have it do its job automatically.

The commented alternative shows another way: subclassing LSTM and overriding call to reset states whenever the layer is stateful before delegating to the original behavior — like modifying the storyteller itself to clear its own memory. That approach works but changes the layer behavior; using a callback keeps the training flow cleaner. Either way, clearing state between full passes helps your LSTM learn stock patterns without leaking memory across unrelated sequences, which is important for reliable price forecasting.

Write functions to turn your work into tidy, reusable steps. Functions make each task clear, let you test pieces separately, and let you try different ideas fast — which is handy when tuning an LSTM for stock forecasts.

Start with data helpers that load CSVs into a DataFrame — a DataFrame is just a smart table that keeps rows and columns. Add simple cleaning steps: sort by date, drop missing rows, and pick the features you need. Also include scaling (e.g., MinMax) so the model learns faster; scaling keeps numbers small and comparable.

Create a sequence builder that slides a fixed window over your time series and returns X (past windows) and y (future targets). LSTMs expect sequences of past values, so this step turns raw prices into the right shape for training.

Write a model factory that builds and compiles your LSTM. Keep architecture choices (layers, units, dropout) as parameters so you can experiment without rewriting code. Add a train function that handles batching, epochs, and callbacks like early stopping.

Finally, include predict, inverse-scale, and evaluate functions that produce forecasts, convert them back to real prices, and compute errors like RMSE. Also add save/load utilities so you can reuse trained models later without retraining. These functions make your pipeline repeatable and easy to debug.

# Function to create an LSTM model, required for KerasClassifier

def create_shallow_LSTM(epochs=1,

LSTM_units=1,

num_samples=1,

look_back=1,

num_features=None,

dropout_rate=0,

recurrent_dropout=0,

verbose=0):

model=Sequential()

model.add(LSTM(units=LSTM_units,

batch_input_shape=(num_samples, look_back, num_features),

stateful=True,

recurrent_dropout=recurrent_dropout))

model.add(Dropout(dropout_rate))

model.add(Dense(1, activation=’sigmoid’, kernel_initializer=keras.initializers.he_normal(seed=1)))

model.compile(loss=’binary_crossentropy’, optimizer=”adam”, metrics=[’accuracy’])

return modelThink of this function as a reusable recipe card that builds a small LSTM network for KerasClassifier: the def line names the recipe create_shallow_LSTM and lists the knobs you can tune like epochs, number of LSTM units, how many past steps to look at (look_back), how many features each step has, and dropout rates. The model=Sequential() line lays out an empty baking tray where we’ll place layers one after another; Sequential means layers are stacked in order. Adding LSTM(…) places a memory cell on the tray: units=LSTM_units sets how much memory the cell has, batch_input_shape=(num_samples, look_back, num_features) fixes the exact shape of inputs — a requirement when the layer is stateful — and stateful=True tells the cell to carry its memory across batches like keeping a simmering stock between ladles; recurrent_dropout applies controlled forgetting on the cell’s internal connections to reduce overfitting (a one-sentence key concept: dropout randomly disables some connections during training so the model doesn’t memorize noise). The Dropout(dropout_rate) layer is another intentional forgetting step applied to the LSTM outputs. The Dense(1, activation=’sigmoid’, kernel_initializer=keras.initializers.he_normal(seed=1)) adds a single output neuron that squashes its value into a probability between 0 and 1, with a carefully chosen initializer to start weights sensibly. model.compile(…) tells Keras how to evaluate and update the network — binary_crossentropy fits a two-way outcome (like up vs down), optimizer=”adam” is the adaptive recipe for adjusting weights, and accuracy is tracked as a metric. Finally return model hands you the ready-to-train model. This compact recipe is ready to be used in your stock forecasting pipeline when you frame the problem as predicting direction or a binary event.

This section covers the data you’ll use to forecast stock prices with an LSTM model, which is a kind of neural network that learns from sequences of numbers. Think of this part as getting your inputs and putting them in the right shape so the model can actually learn patterns over time.

Start with historical market data like the date, open/high/low/close prices and volume. You can add simple technical indicators if you want, such as moving averages; a DataFrame is just a smart table that keeps these columns neatly aligned by date. Collecting the right columns now makes the modeling steps later much simpler.

Clean the data first: fill or drop missing values and make sure timestamps are continuous. Scale the numbers so they are on a similar range — scaling (also called normalization) just means shrinking values so the model trains faster and more reliably. This step prevents very large price numbers from dominating learning.

Build input sequences by sliding a fixed-length window over the time series; each window becomes one training example and the next price is the label. LSTMs need these ordered sequences to learn how past values influence future ones. Finally, split into train, validation and test sets without shuffling so the test set truly represents future data and you can evaluate realistic performance.

This step is about bringing in the raw data*— the original, unprocessed stock prices and related fields your model will learn from. Raw data means the numbers as they came from a file or service, before you clean or transform them. Getting this right matters because everything that follows (cleaning, scaling, building sequences) depends on the input.

You’ll usually load historical price files like CSVs (a simple text file where commas separate columns) or pull data from an API such as Yahoo Finance or Alpha Vantage. Typical columns are date, open, high, low, close, and volume. Make sure the dates are in order and that you know the timezone; misaligned timestamps can confuse a time-based model. Also check for missing rows or obvious errors — it’s easier to fix these now than after you build your dataset.

For an LSTM (a type of neural network that learns from sequences of numbers, like price over time) you’ll later turn this raw table into sliding windows of past prices. Importing clean, well-organized raw data prepares you for that step and reduces surprises during training.

# Imports data

start_sp=datetime.datetime(1980, 1, 1)

end_sp=datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 28)

yf.pdr_override()

sp500=pdr.get_data_yahoo(’^GSPC’,

start_sp,

end_sp)

sp500.shapeWe’re starting by saying what we want: grab historical market data so our forecasting model has something to learn from. The first two lines set a time window: start_sp = datetime.datetime(1980, 1, 1) and end_sp = datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 28). Think of those as setting the start and end marks on a calendar — a datetime object represents a specific point in time used for slicing the data. That window tells the downloader how much history to fetch.

Next, yf.pdr_override() quietly swaps in yfinance as the backend for the pandas-datareader helper, like changing the mail carrier so Yahoo’s finance API can deliver the data in a format pandas understands. Then pdr.get_data_yahoo(‘^GSPC’, start_sp, end_sp) places the request: it asks for S&P 500 historical prices between the dates you picked, and returns a table-like object called a DataFrame which holds columns like Open, High, Low, Close, Volume.

Finally, sp500.shape is queried so you can see the size of that table — shape returns a tuple (rows, columns), and knowing the number of rows tells you how many time steps you have. With the S&P 500 series loaded and its dimensions known, you’re ready to transform those rows into sequences and feed them into the LSTM to learn price patterns.

Creating features means building the inputs the model will use to learn. Think of *features* as the signals you feed an LSTM so it can spot patterns, and the *target* as the future price you want it to predict. This step matters because the wrong inputs make learning slow or misleading.

Start with simple, obvious things: past prices and returns, trading volume, and basic moving averages. You can add technical indicators like RSI or MACD, but explain them in one line when you add them (for example, RSI is a measure of recent gains versus losses). Keep each feature as a number the model can use.

Scale your features so they live on similar ranges — that’s called normalization, and it helps the LSTM train faster and avoid getting stuck. Be careful to avoid data leakage: only use information available at the prediction time, never peeking into future data.

Finally, turn the time series into sequences the LSTM can read. Use a sliding window to make short past histories (timesteps) and their matching targets. This reshapes your table into a 3D array: samples × timesteps × features, which is the format LSTMs expect.

# Compute the logarithmic returns using the Closing price

sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]=np.log(sp500[’Close’] / sp500[’Close’].shift(1))

# Compute logarithmic returns using the pandas rolling mean function

sp500[’Log_Ret_1w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=5).sum()

sp500[’Log_Ret_2w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=10).sum()

sp500[’Log_Ret_3w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=15).sum()

sp500[’Log_Ret_4w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=20).sum()

sp500[’Log_Ret_8w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=40).sum()

sp500[’Log_Ret_12w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=60).sum()

sp500[’Log_Ret_16w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=80).sum()

sp500[’Log_Ret_20w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=100).sum()

sp500[’Log_Ret_24w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=120).sum()

sp500[’Log_Ret_28w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=140).sum()

sp500[’Log_Ret_32w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=160).sum()

sp500[’Log_Ret_36w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=180).sum()

sp500[’Log_Ret_40w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=200).sum()

sp500[’Log_Ret_44w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=220).sum()

sp500[’Log_Ret_48w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=240).sum()

sp500[’Log_Ret_52w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=260).sum()

sp500[’Log_Ret_56w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=280).sum()

sp500[’Log_Ret_60w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=300).sum()

sp500[’Log_Ret_64w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=320).sum()

sp500[’Log_Ret_68w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=340).sum()

sp500[’Log_Ret_72w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=360).sum()

sp500[’Log_Ret_76w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=380).sum()

sp500[’Log_Ret_80w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=400).sum()

# Compute Volatility using the pandas rolling standard deviation function

sp500[’Vol_1w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=5).std()*np.sqrt(5)

sp500[’Vol_2w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=10).std()*np.sqrt(10)

sp500[’Vol_3w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=15).std()*np.sqrt(15)

sp500[’Vol_4w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=20).std()*np.sqrt(20)

sp500[’Vol_8w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=40).std()*np.sqrt(40)

sp500[’Vol_12w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=60).std()*np.sqrt(60)

sp500[’Vol_16w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=80).std()*np.sqrt(80)

sp500[’Vol_20w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=100).std()*np.sqrt(100)

sp500[’Vol_24w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=120).std()*np.sqrt(120)

sp500[’Vol_28w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=140).std()*np.sqrt(140)

sp500[’Vol_32w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=160).std()*np.sqrt(160)

sp500[’Vol_36w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=180).std()*np.sqrt(180)

sp500[’Vol_40w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=200).std()*np.sqrt(200)

sp500[’Vol_44w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=220).std()*np.sqrt(220)

sp500[’Vol_48w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=240).std()*np.sqrt(240)

sp500[’Vol_52w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=260).std()*np.sqrt(260)

sp500[’Vol_56w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=280).std()*np.sqrt(280)

sp500[’Vol_60w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=300).std()*np.sqrt(300)

sp500[’Vol_64w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=320).std()*np.sqrt(320)

sp500[’Vol_68w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=340).std()*np.sqrt(340)

sp500[’Vol_72w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=360).std()*np.sqrt(360)

sp500[’Vol_76w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=380).std()*np.sqrt(380)

sp500[’Vol_80w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).rolling(window=400).std()*np.sqrt(400)

# Compute Volumes using the pandas rolling mean function

sp500[’Volume_1w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Volume’]).rolling(window=5).mean()

sp500[’Volume_2w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Volume’]).rolling(window=10).mean()

sp500[’Volume_3w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Volume’]).rolling(window=15).mean()

sp500[’Volume_4w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Volume’]).rolling(window=20).mean()

sp500[’Volume_8w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Volume’]).rolling(window=40).mean()

sp500[’Volume_12w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Volume’]).rolling(window=60).mean()

sp500[’Volume_16w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Volume’]).rolling(window=80).mean()

sp500[’Volume_20w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Volume’]).rolling(window=100).mean()

sp500[’Volume_24w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Volume’]).rolling(window=120).mean()

sp500[’Volume_28w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Volume’]).rolling(window=140).mean()

sp500[’Volume_32w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Volume’]).rolling(window=160).mean()

sp500[’Volume_36w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Volume’]).rolling(window=180).mean()

sp500[’Volume_40w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Volume’]).rolling(window=200).mean()

sp500[’Volume_44w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Volume’]).rolling(window=220).mean()

sp500[’Volume_48w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Volume’]).rolling(window=240).mean()

sp500[’Volume_52w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Volume’]).rolling(window=260).mean()

sp500[’Volume_56w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Volume’]).rolling(window=280).mean()

sp500[’Volume_60w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Volume’]).rolling(window=300).mean()

sp500[’Volume_64w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Volume’]).rolling(window=320).mean()

sp500[’Volume_68w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Volume’]).rolling(window=340).mean()

sp500[’Volume_72w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Volume’]).rolling(window=360).mean()

sp500[’Volume_76w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Volume’]).rolling(window=380).mean()

sp500[’Volume_80w’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Volume’]).rolling(window=400).mean()

# Label data: Up (Down) if the the 1 month (≈ 21 trading days) logarithmic return increased (decreased)

sp500[’Return_Label’]=pd.Series(sp500[’Log_Ret_1d’]).shift(-21).rolling(window=21).sum()

sp500[’Label’]=np.where(sp500[’Return_Label’] > 0, 1, 0)

# Drop NA´s

sp500=sp500.dropna(”index”)

sp500=sp500.drop([’Open’, ‘High’, ‘Low’, ‘Close’, ‘Adj Close’, ‘Volume’, “Return_Label”], axis=1)Think of your data frame as a long journal of daily market life; the first line turns raw closing prices into a gentle measure of change by taking the logarithm of today’s close divided by yesterday’s — log returns are a compact, additive way to measure percentage changes. The next block builds a family of multi-week return features by sliding a window across that daily log-return column and summing the values inside each window; a rolling window is like a postage stamp you slide along the timeline so each day collects the cumulative log-return over the past 5, 10, 15 … up to 400 days, giving you short- and long-horizon return signals (summing log returns gives the total log return over the period).

Right after, volatility is computed by taking the rolling standard deviation of daily log returns and multiplying by the square root of the window length — standard deviation quantifies typical fluctuation size, and scaling by the square root of time converts that daily variability into the variability over the whole window. Then volumes are smoothed in the same sliding-window spirit by taking rolling means of the raw Volume column so each date also carries short- and long-term average trading activity.

To create a target for prediction, the code sums the next 21 trading-day log returns (it shifts the series backward and then rolls), so every row gets a forward-looking one-month return; a binary Label marks 1 if that forward return is positive and 0 otherwise, turning future movement into a classification target. Finally, any rows with missing values are dropped and raw price columns removed so the frame contains only engineered features and the label. All these features become the inputs your LSTM can learn temporal patterns from when forecasting stock movement.

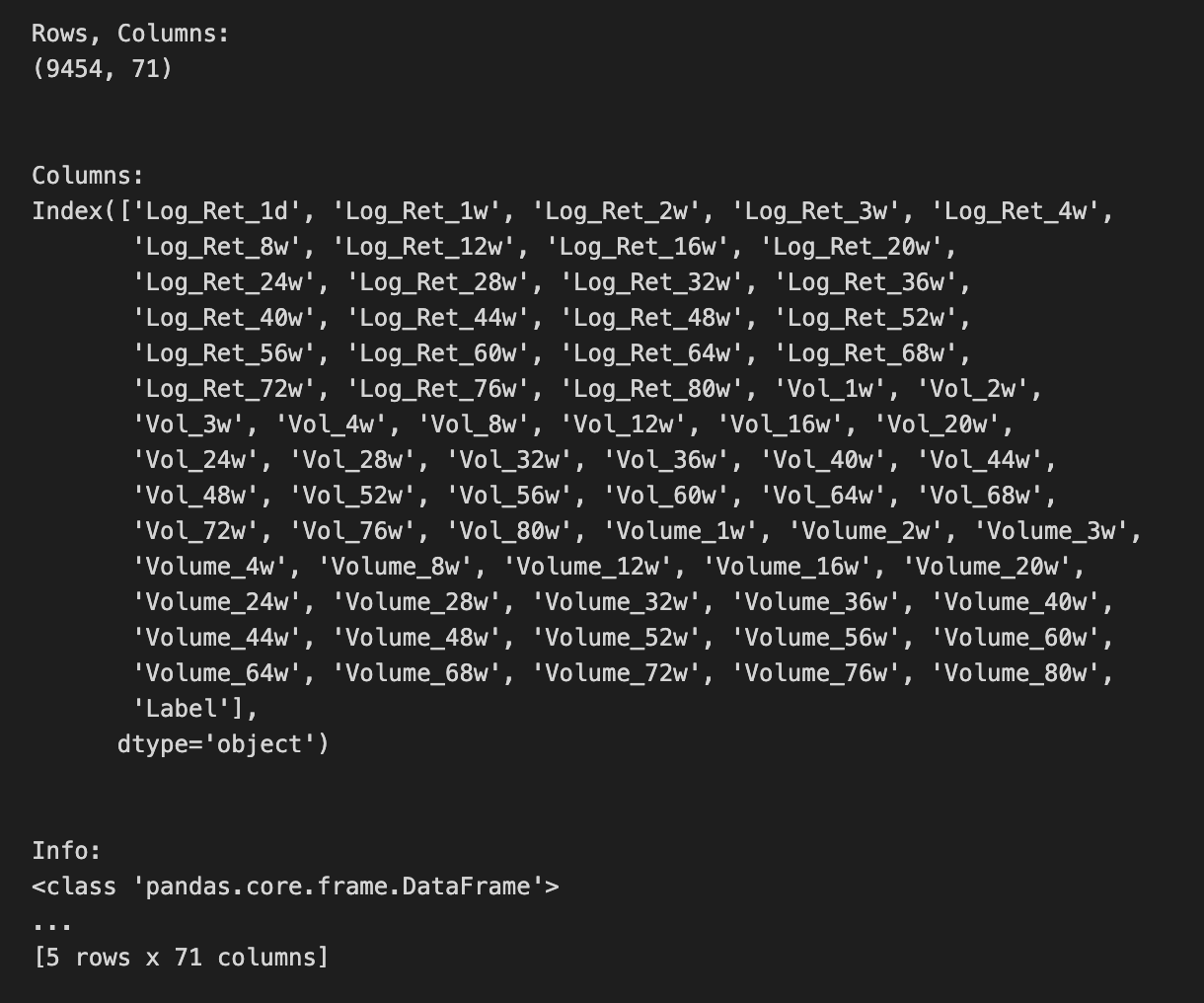

Start by getting a feel for the data: how many rows and columns it has, what the column names are, and what types each column is (numbers, text, or dates). A DataFrame is just a smart table that holds this data. This quick check tells you if you loaded the right file and what needs fixing before modeling.

Make sure your date column is really a date and that the rows are sorted by time. LSTMs are a kind of neural network that read sequences, so they need the data in the right order and with a proper time index. Converting and sorting now avoids subtle errors later when you build sequences.

Look for missing or duplicate rows and note any unusual values. Count holes and duplicates so you can decide how to fill or drop them. Cleaning these issues first keeps your model from learning junk.

Compute simple summary stats — mean, standard deviation, min, max — and peek at correlations between features. These numbers show the data’s scale and relationships, which helps choose scaling and which inputs matter most. A quick plot of price over time also helps you spot trends or sudden jumps that may need special handling.

# Show rows and columns

print(”Rows, Columns:”);print(sp500.shape);print(”\n”)

# Describe DataFrame columns

print(”Columns:”);print(sp500.columns);print(”\n”)

# Show info on DataFrame

print(”Info:”);print(sp500.info()); print(”\n”)

# Count Non-NA values

print(”Non-NA:”);print(sp500.count()); print(”\n”)

# Show head

print(”Head”);print(sp500.head()); print(”\n”)

# Show tail

print(”Tail”);print(sp500.tail());print(”\n”)

# Show summary statistics

print(”Summary statistics:”);print(sp500.describe());print(”\n”)We begin by taking a friendly inventory of the sp500 dataset to make sure our inputs are sound before we feed them into an LSTM. A DataFrame is a 2D labeled data structure, like a spreadsheet, and the first printed pair shows its shape so we immediately know how many rows (time steps) and columns (features) we have — think of it as measuring the size of the room we’ll be working in. Printing the column labels then tells us what each feature is named, like reading the ingredient labels on a shelf so we know which variables are available. Calling the info method acts like looking at the building blueprint: it lists each column’s data type and memory footprint and flags non-null counts; data types are critical because an ML model expects numeric inputs, not text. Counting non-NA values is our attendance check, a direct way to spot missing data that we’ll need to handle. Showing the head and tail is like peeking at the first and last pages of a logbook to confirm ordering and to inspect a few actual records for obvious issues. Finally, the describe call produces a statistical report card — count, mean, standard deviation, min, quartiles and max — letting us see distributions and potential outliers at a glance, which guides scaling or transformation choices. All these steps help ensure the time series is clean, typed correctly, and well-understood before we build and train the LSTM forecast.

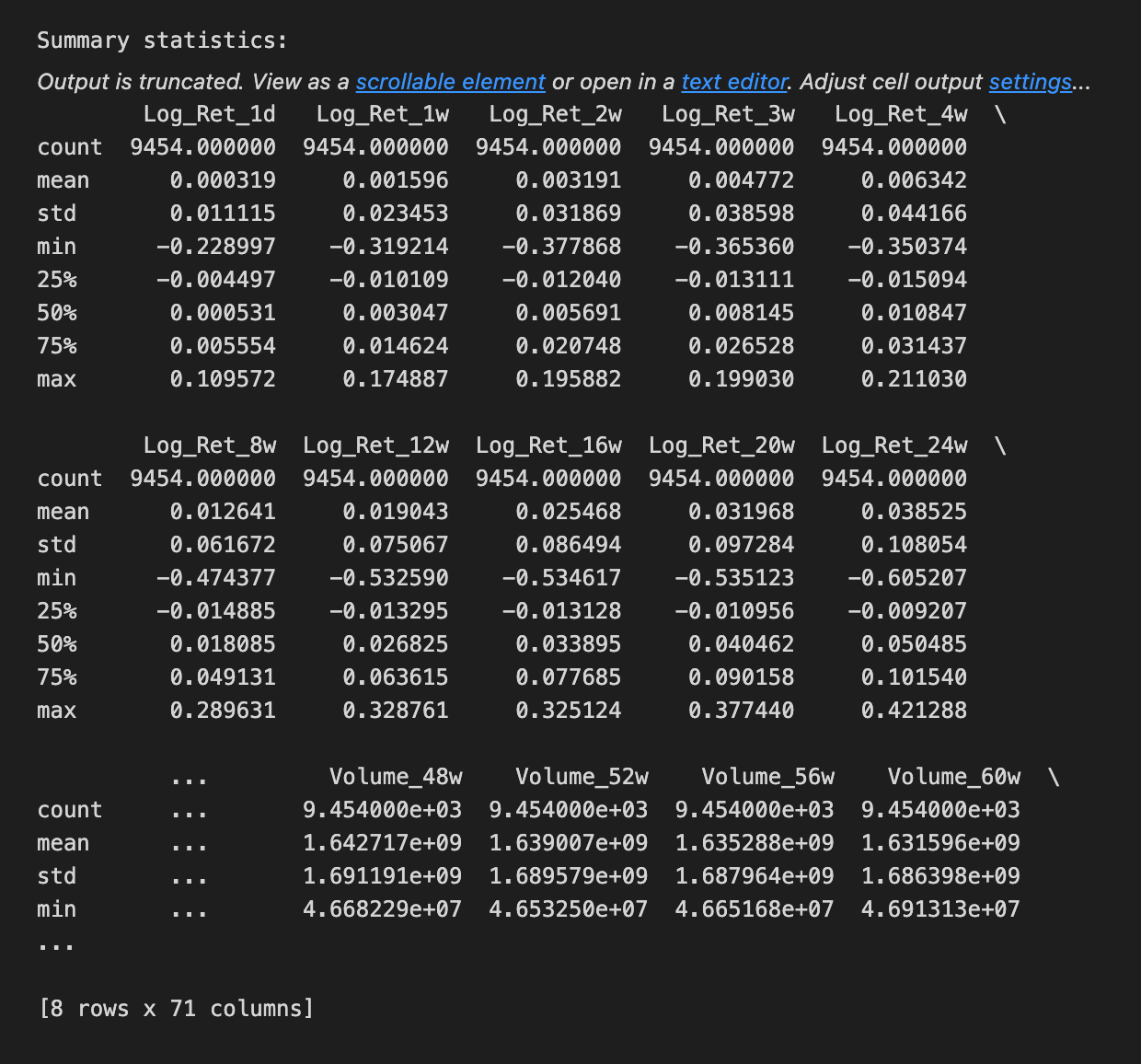

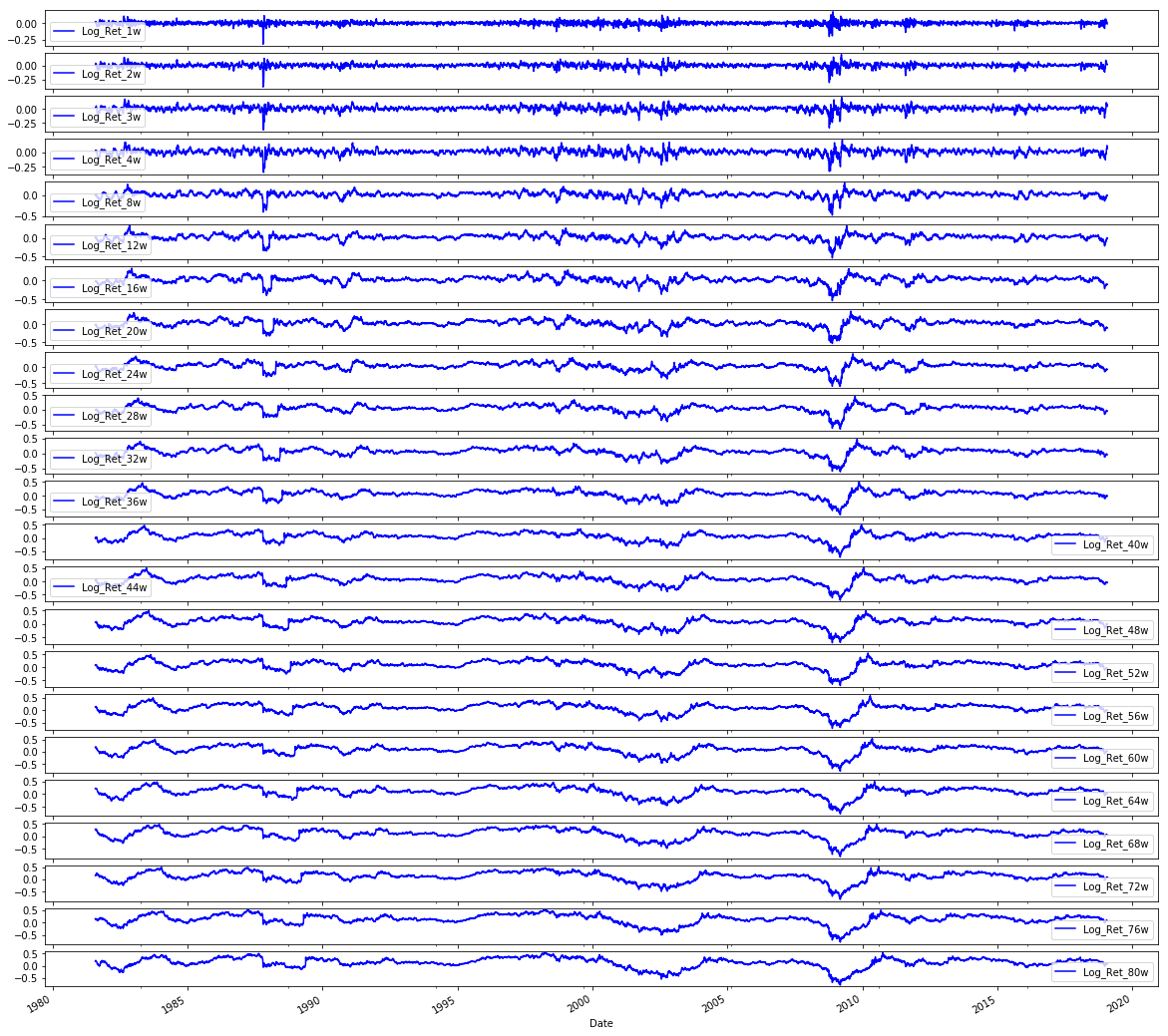

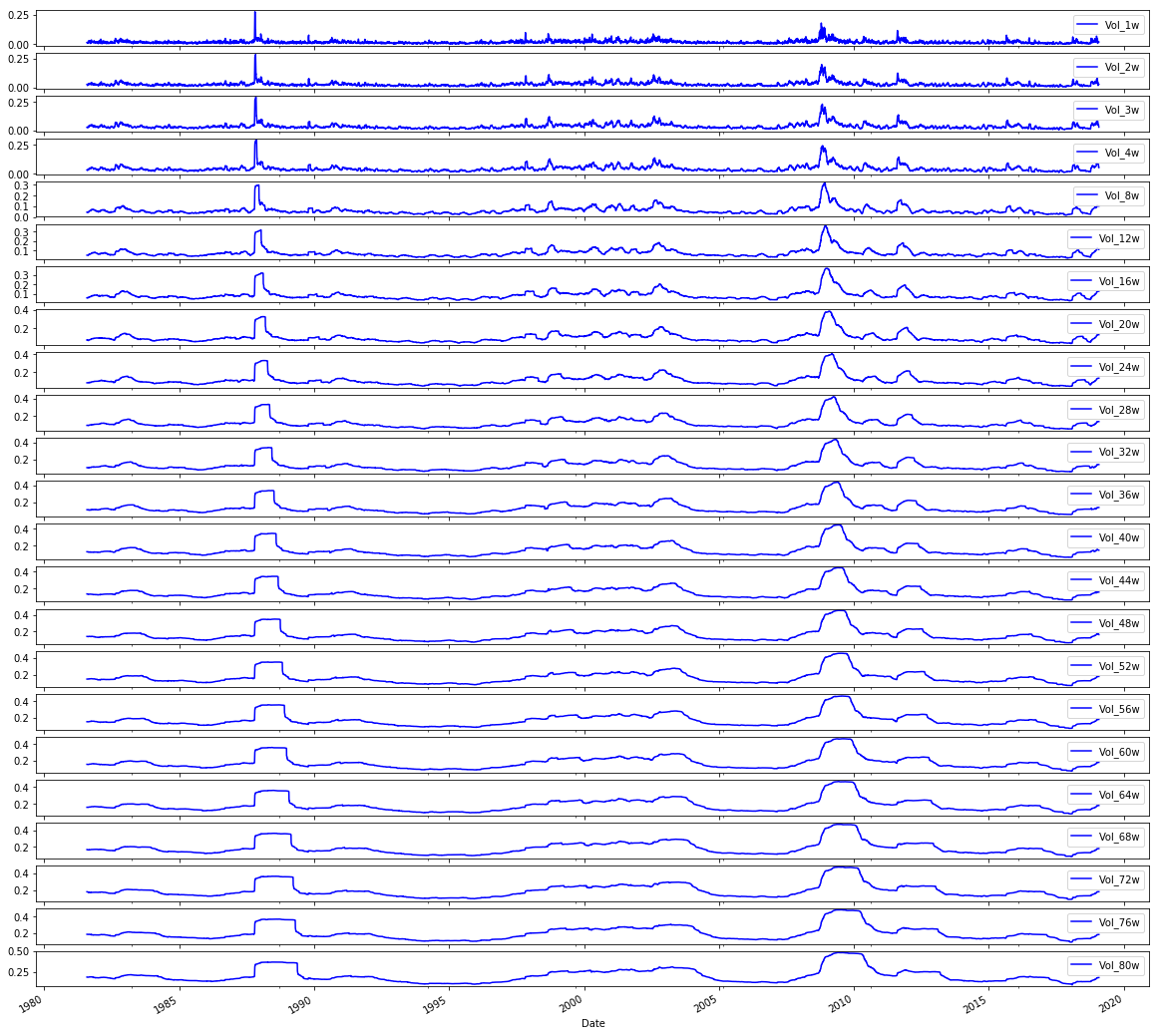

Before you feed anything into the LSTM (that’s a kind of neural network that learns from sequences, like past prices), take a moment to plot the data. Seeing the raw price history helps you spot obvious trends, repeating patterns, or weird spikes that could confuse the model. This quick look also helps you pick sensible settings later, like how many past days the model should consider.

Plot both the raw prices and any transformed versions you’ll use, such as scaled values (scaling just means squashing numbers into a smaller range so the model learns better). Mark where you split the data into training and testing sets so you can see whether the test portion looks like the training portion. If they look very different, the model may struggle.

After you run the model, plot predicted values against the actual prices on the same chart so you can see how well the LSTM follows reality. Also plot residuals (the differences between prediction and truth); residuals let you spot consistent bias or patterns the model missed.

Keep charts simple and readable: label axes, include a legend, and use dates on the x-axis. Good plots are cheap and fast, and they often save you hours of debugging later.

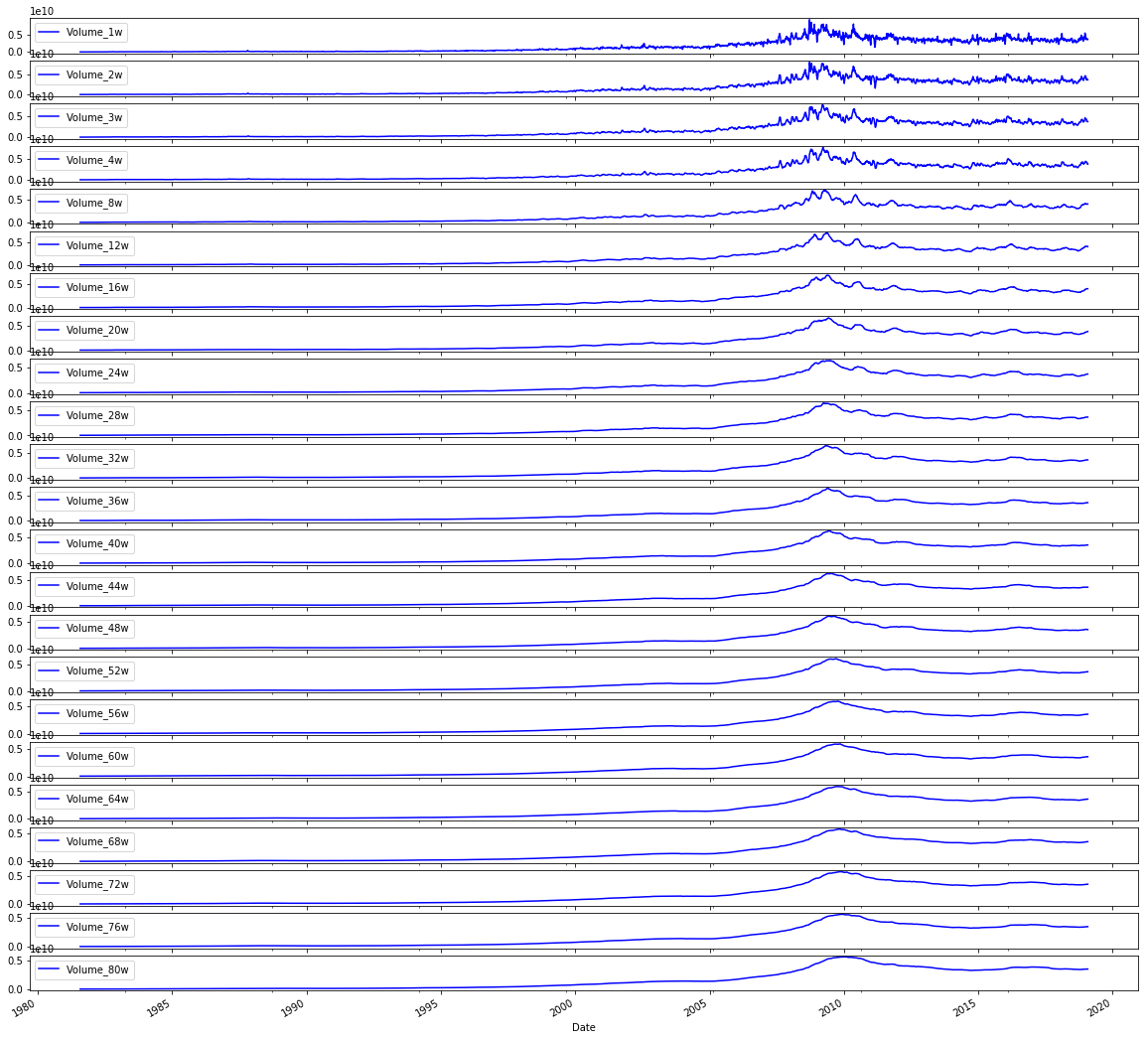

# Plot the logarithmic returns

sp500.iloc[:,1:24].plot(subplots=True, color=’blue’, figsize=(20, 20));We’re trying to lay out the logarithmic returns for a set of S&P 500 series so we can visually inspect how each return path behaves over time. The line begins with sp500, which is a pandas DataFrame holding the series; iloc is an integer-location based slicer like cutting a loaf by positions, and iloc[:, 1:24] means “take every row but only the columns from position 1 up to (but not including) 24” — that exclusive upper bound is a key slicing rule. After selecting those columns we call .plot(), which is pandas’ friendly wrapper around matplotlib that turns columns into lines on a chart; giving subplots=True is like putting each ingredient into its own bowl so every column gets its own small chart to avoid overlap and make patterns easy to see. The color=’blue’ argument simply paints every line blue so the visuals are consistent, and figsize=(20, 20) sets the canvas size in inches so each small chart has room to breathe. The trailing semicolon is a notebook nicety that suppresses the textual return value display for a cleaner output. By spreading the log-returns across separate plots you can quickly spot trends, volatility shifts, or anomalies before you proceed to preprocessing and feeding the data into an LSTM for forecasting.

# Plot the Volatilities

sp500.iloc[:,24:47].plot(subplots=True, color=’blue’,figsize=(20, 20));We want to take a look at a set of volatility series from an S&P 500 table, so the comment tells us the intent: “Plot the Volatilities.” Think of the DataFrame like a big cookbook where each column is a recipe card for one volatility series; sp500.iloc[:,24:47] is the act of pulling out a specific stack of cards by position — iloc is a positional indexer that selects rows and columns by number rather than by name, and here : means every row while 24:47 picks columns 24 up to 46.

Once those columns are selected, calling .plot(…) asks pandas to draw them, and the parameters shape how the drawings appear. Setting subplots=True is like asking for one individual plate per recipe so each series gets its own small chart rather than all being layered together; key concept: subplots create separate axes so you can compare shapes without overlap. color=’blue’ paints every line the same calm blue so the eye tracks volatility consistently, and figsize=(20,20) hands matplotlib a large canvas in inches so each small chart has plenty of room. The trailing semicolon is a tiny Jupyter notebook trick to suppress printing of the matplotlib object and leave only the visual.

Seeing these volatility traces helps you spot trends, spikes, or quiet stretches before you feed the cleaned, understood series into your LSTM forecasting pipeline.

# Plot the Volumes

sp500.iloc[:,47:70].plot(subplots=True, color=’blue’, figsize=(20, 20));We want to take a quick visual tour of trading volumes before we feed anything into the model, because a picture often reveals trends, spikes, or gaps that numbers alone hide. The comment at the top simply says “Plot the Volumes” to remind us of that intention.

The line that follows reaches into the sp500 table and selects a block of columns by position: iloc[:,47:70] picks every row (the “:” is like saying “give me the whole timeline”) and columns 47 through 69 by integer position. Key concept: iloc is integer-location based indexing used to select rows and columns by their numerical positions. After selecting those columns, .plot(subplots=True, color=’blue’, figsize=(20, 20)) lays out a set of line charts — one small chart for each chosen column — so we can compare individual volume series side by side. Key concept: subplots=True tells the plotting engine to create separate axes for each column instead of overlaying them on a single plot. The color argument keeps all lines blue for visual consistency, and figsize=(20, 20) makes a large grid so each mini-chart is readable. The trailing semicolon is a quiet nudge to the notebook to show only the visuals, not the plot object.

Seeing these volume patterns helps you decide normalization, outlier handling, or which series to include as inputs to your LSTM forecast.

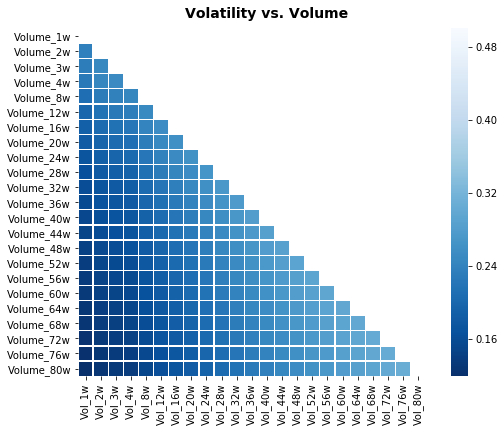

# Plot correlation matrix

focus_cols=sp500.iloc[:,24:47].columns

corr=sp500.iloc[:,24:70].corr().filter(focus_cols).drop(focus_cols)

mask=np.zeros_like(corr); mask[np.triu_indices_from(mask)]=True # we use mask to plot only part of the matrix

heat_fig, (ax)=plt.subplots(1, 1, figsize=(9,6))

heat=sns.heatmap(corr,

ax=ax,

mask=mask,

vmax=.5,

square=True,

linewidths=.2,

cmap=”Blues_r”)

heat_fig.subplots_adjust(top=.93)

heat_fig.suptitle(’Volatility vs. Volume’, fontsize=14, fontweight=’bold’)

plt.savefig(’heat1.eps’, dpi=200, format=’eps’);We’re trying to reveal relationships — a little conversation — between a focused set of volatility columns and a broader set of variables (like volume measures), so we can spot which signals might help the LSTM learn. The first line selects the column names in positions 24 through 46: think of it as picking the recipe cards you care most about. Then a correlation table is built from columns 24 through 69, and from that table we keep only the columns matching our focus cards and remove those same labels from the rows, so the table becomes a cross-talk matrix showing how other features correlate with the chosen volatility features. A correlation matrix is simply a compact way to measure how two variables move together.

Next, a mask array is created that matches the correlation matrix shape and has the upper triangle marked; imagine putting a privacy screen over half a mirror so you only see one side of a symmetric relationship. A matplotlib figure and axis are prepared as a canvas and frame for the drawing. Seaborn’s heatmap then paints the correlation values as colors on that canvas, using the mask to hide the mirrored half, capping color intensity at 0.5 so extreme values don’t dominate, making cells square for neatness, and using a reversed blue palette so stronger correlations read visually as darker tones. The figure spacing and a bold title are set to make the plot presentable, and finally the image is exported to an EPS file for high-quality inclusion in reports. Seeing which features co-move with volatility helps inform which inputs to feed your LSTM forecasting model.

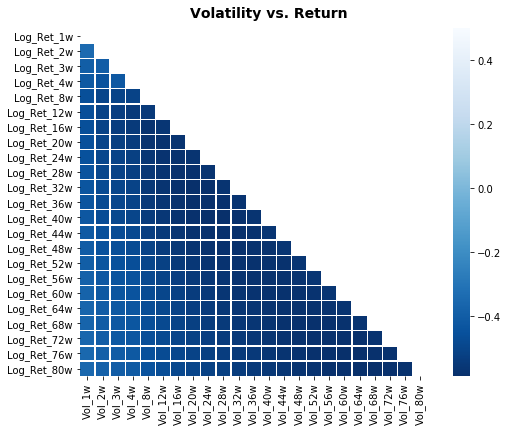

# Plot correlation matrix

focus_cols=sp500.iloc[:,24:47].columns

corr=sp500.iloc[:,1:47].corr().filter(focus_cols).drop(focus_cols)

mask=np.zeros_like(corr); mask[np.triu_indices_from(mask)]=True # we use mask to plot only part of the matrix

heat_fig, (ax)=plt.subplots(1, 1, figsize=(9,6))

heat=sns.heatmap(corr,

ax=ax,

mask=mask,

vmax=.5,

square=True,

linewidths=.2,

cmap=”Blues_r”)

heat_fig.subplots_adjust(top=.93)

heat_fig.suptitle(’Volatility vs. Return’, fontsize=14, fontweight=’bold’)

plt.savefig(’heat2.eps’, dpi=200, format=’eps’);We’re trying to build a little map that shows how volatility-related columns relate to return-related columns so we can pick sensible inputs for our LSTM. First, we pick the columns we want to focus on by slicing the table: focus_cols = sp500.iloc[:,24:47].columns grabs the names of those columns so we can highlight their relationships. Next, we compute pairwise correlations across a wider set with sp500.iloc[:,1:47].corr() — correlation is a simple measure of linear association between two series, ranging from -1 to 1 — and then we .filter(focus_cols).drop(focus_cols) to keep only the correlations of other features against our focus columns while removing the diagonal self-comparisons.

To make the map easier to read we create a mask: mask=np.zeros_like(corr) creates an array the same shape as the correlation table, and mask[np.triu_indices_from(mask)]=True fills the upper triangle with True; a mask is just a way to hide parts of the plot so we avoid redundant mirrored information, like folding a map to look at one side.

We then make a figure and axis with plt.subplots(1, 1, figsize=(9,6)) to reserve plotting space, and call sns.heatmap(…) to draw the colored grid where each cell’s color encodes correlation strength. The arguments control the axis, apply the mask, cap the color scale at 0.5 so moderate correlations stand out, force square cells for neatness, add thin lines between cells, and choose a reversed blue palette. heat_fig.subplots_adjust(top=.93) makes room for the title, heat_fig.suptitle(…) stamps a bold heading, and plt.savefig(‘heat2.eps’, dpi=200, format=’eps’) writes the image to disk.

Seeing those relationships helps us decide which features to feed into the LSTM and spot multicollinearity before we build the forecasting model.

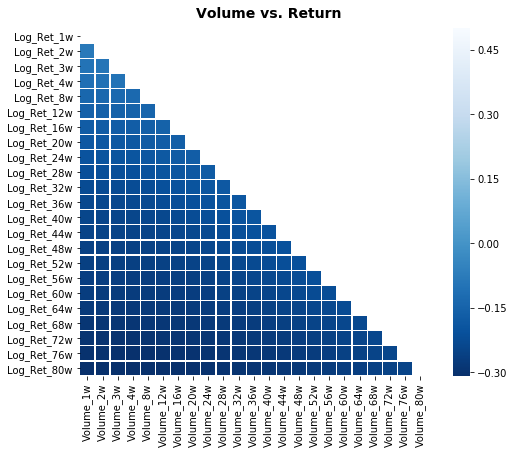

# Plot correlation matrix

focus_cols=sp500.iloc[:,47:70].columns

corr=sp500.iloc[:, np.r_[1:24, 47:70]].corr().filter(focus_cols).drop(focus_cols)

mask=np.zeros_like(corr); mask[np.triu_indices_from(mask)]=True # we use mask to plot only part of the matrix

heat_fig, (ax)=plt.subplots(1, 1, figsize=(9,6))

heat=sns.heatmap(corr,

ax=ax,

mask=mask,

vmax=.5,

square=True,

linewidths=.2,

cmap=”Blues_r”)

heat_fig.subplots_adjust(top=.93)

heat_fig.suptitle(’Volume vs. Return’, fontsize=14, fontweight=’bold’)

plt.savefig(’heat3.eps’, dpi=200, format=’eps’);We want to visualize how a group of “focus” columns relate to a broader set of variables so you can spot which features (like volumes) correlate with returns. The first line picks those focus columns by slicing the DataFrame like choosing a subset of ingredients from a big pantry: focus_cols = sp500.iloc[:,47:70].columns selects columns 47 through 69. Next, a wider selection of columns is assembled with numpy’s r_ to combine ranges, then .corr() computes pairwise relationships among them; correlation measures the linear relationship between two variables and helps us see who moves together. The .filter(focus_cols).drop(focus_cols) keeps only the columns corresponding to the focus set while dropping their mirror rows, producing a rectangular table of how every other variable correlates with each focus column.

To keep the plot uncluttered, a mask is made: np.zeros_like creates an array of zeros matching the correlation table and np.triu_indices_from sets the upper triangle to True so it will be hidden; a mask is a boolean filter that hides parts of the visualization for clarity. plt.subplots creates a figure and axes (think of a function as a reusable recipe card that lays out your canvas), and sns.heatmap paints the correlation values using the mask, limiting the color scale with vmax=.5, making cells square, adding thin separators, and using a reversed blue colormap so stronger correlations stand out. The figure is nudged with subplots_adjust, given a bold title, and finally saved as an EPS file with plt.savefig for high-quality output. Viewing these relationships helps you choose and engineer features before feeding them into the LSTM forecasting model.

First, hold back a chunk of the most recent prices as your *test* data. This is the unseen future your model will try to predict, so keep it out of training and validation. For time series, that means slicing by date rather than shuffling rows, because mixing past and future would give an unrealistic advantage.

Next, prepare the training and validation sets and any transformations you need, like scaling or turning prices into sliding windows of past values. Scaling makes numbers easier for models to learn. Sliding windows turn a long list of prices into many short sequences the model can use to learn patterns.

Make two model sets: simple baselines and the LSTM models. A baseline is a straightforward method, like “predict tomorrow will equal today” or a moving average, and it helps you check whether the fancy model really improves things. An *LSTM* is a kind of neural network that remembers sequences, useful for time-based patterns.

Keep the test set the same for both model types so comparisons are fair. Save your preprocessing steps and model versions so you can reproduce results and understand why one approach wins. This prepares you to evaluate performance honestly and iterate from there.

# Model Set 1: Volatility

# Baseline

X_train_1, X_test_1, y_train_1, y_test_1=train_test_split(sp500.iloc[:,24:47], sp500.iloc[:,70], test_size=0.1 ,shuffle=False, stratify=None)

# LSTM

# Input arrays should be shaped as (samples or batch, time_steps or look_back, num_features):

X_train_1_lstm=X_train_1.values.reshape(X_train_1.shape[0], 1, X_train_1.shape[1])

X_test_1_lstm=X_test_1.values.reshape(X_test_1.shape[0], 1, X_test_1.shape[1])

# Model Set 2: Return

X_train_2, X_test_2, y_train_2, y_test_2=train_test_split(sp500.iloc[:,1:24], sp500.iloc[:,70], test_size=0.1 ,shuffle=False, stratify=None)

# LSTM

# Input arrays should be shaped as (samples or batch, time_steps or look_back, num_features):

X_train_2_lstm=X_train_2.values.reshape(X_train_2.shape[0], 1, X_train_2.shape[1])

X_test_2_lstm=X_test_2.values.reshape(X_test_2.shape[0], 1, X_test_2.shape[1])

# Model Set 3: Volume

X_train_3, X_test_3, y_train_3, y_test_3=train_test_split(sp500.iloc[:,47:70], sp500.iloc[:,70], test_size=0.1 ,shuffle=False, stratify=None)

# LSTM

# Input arrays should be shaped as (samples or batch, time_steps or look_back, num_features):

X_train_3_lstm=X_train_3.values.reshape(X_train_3.shape[0], 1, X_train_3.shape[1])

X_test_3_lstm=X_test_3.values.reshape(X_test_3.shape[0], 1, X_test_3.shape[1])

# Model Set 4: Volatility and Return

X_train_4, X_test_4, y_train_4, y_test_4=train_test_split(sp500.iloc[:,1:47], sp500.iloc[:,70], test_size=0.1 ,shuffle=False, stratify=None)

# LSTM

# Input arrays should be shaped as (samples or batch, time_steps or look_back, num_features):

X_train_4_lstm=X_train_4.values.reshape(X_train_4.shape[0], 1, X_train_4.shape[1])

X_test_4_lstm=X_test_4.values.reshape(X_test_4.shape[0], 1, X_test_4.shape[1])

# Model Set 5: Volatility and Volume

X_train_5, X_test_5, y_train_5, y_test_5=train_test_split(sp500.iloc[:,24:70], sp500.iloc[:,70], test_size=0.1 ,shuffle=False, stratify=None)

# LSTM

# Input arrays should be shaped as (samples or batch, time_steps or look_back, num_features):

X_train_5_lstm=X_train_5.values.reshape(X_train_5.shape[0], 1, X_train_5.shape[1])

X_test_5_lstm=X_test_5.values.reshape(X_test_5.shape[0], 1, X_test_5.shape[1])

# Model Set 6: Return and Volume

X_train_6, X_test_6, y_train_6, y_test_6=train_test_split(pd.concat([sp500.iloc[:,1:24], sp500.iloc[:,47:70]], axis=1), sp500.iloc[:,70], test_size=0.1 ,shuffle=False, stratify=None)

# LSTM

# Input arrays should be shaped as (samples or batch, time_steps or look_back, num_features):

X_train_6_lstm=X_train_6.values.reshape(X_train_6.shape[0], 1, X_train_6.shape[1])

X_test_6_lstm=X_test_6.values.reshape(X_test_6.shape[0], 1, X_test_6.shape[1])

# Model Set 7: Volatility, Return and Volume

X_train_7, X_test_7, y_train_7, y_test_7=train_test_split(sp500.iloc[:,1:70], sp500.iloc[:,70], test_size=0.1 ,shuffle=False, stratify=None)

# LSTM

# Input arrays should be shaped as (samples or batch, time_steps or look_back, num_features):

X_train_7_lstm=X_train_7.values.reshape(X_train_7.shape[0], 1, X_train_7.shape[1])

X_test_7_lstm=X_test_7.values.reshape(X_test_7.shape[0], 1, X_test_7.shape[1])Imagine we’re preparing seven different recipe variations to teach a kitchen robot (an LSTM) how to predict tomorrow’s price. Each set begins by cutting the master spreadsheet into ingredients and a single dish to predict: the features come from selected column ranges and the dish is the value in column 70. The train_test_split line is like reserving 10% of the samples as a held-out tasting set (test_size=0.1) while keeping the time order intact (shuffle=False) — for time series, preserving order is a key concept because shuffling would mix past and future.

For Model Set 1 we slice columns 24 through 46 as the volatility ingredients and split them into training and testing inputs and targets. Then we reshape the flat tables into the three-dimensional form an LSTM expects: samples, time_steps, features. An LSTM expects a 3D input shaped as (samples, time_steps, features). Here we reshape so time_steps equals 1, effectively giving the model single-step windows of features, like handing it one recipe card at a time. Model Sets 2 and 3 repeat that process for return columns (1–23) and volume columns (47–69) respectively.

Model Set 4 combines volatility and return by expanding the column slice to 1–46; Set 5 combines volatility and volume with 24–69. Set 6 stitches return and volume together explicitly using concat, which is like gluing two ingredient lists side-by-side before splitting. Finally Set 7 uses all features 1–69 so the model sees every available signal. Each subsequent reshape converts the table into samples × 1 × features so the LSTM can consume them. By preparing these seven flavored datasets we can compare how volatility, return, and volume — alone or together — help an LSTM forecast stock prices.

Now we want to *show the label distribution* — that means look at how the target values (the numbers you’re trying to predict) are spread out. The “label” is just the thing the model learns to predict, and “distribution” means whether those values cluster, are skewed, or have lots of outliers.

This matters for an LSTM (an LSTM is a kind of neural network that learns from sequences, like past prices). If most labels are similar or bunched in one range, the model might just learn that common value instead of meaningful patterns. Checking the distribution helps you spot skew, extreme jumps, or class imbalance if you turned price movement into categories like “up” and “down.”

A simple histogram or box plot and a quick table of counts is usually enough. If you see skew or big outliers, consider rescaling the labels, clipping extremes, or using class weights or sampling strategies — these fixes make training more stable and fair. Showing the label distribution prepares you to choose the right loss, scaling, and evaluation steps for better forecasts.

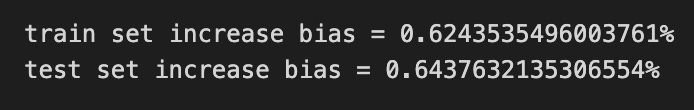

print(”train set increase bias = “+ str(np.mean(y_train_7==1))+”%”)

print(”test set increase bias = “ + str(np.mean(y_test_7==1))+”%”)Think of the program as a little scoreboard that tells you whether your training and test datasets are biased toward days when the stock goes up. The first line prints a friendly label “train set increase bias = “ and then tacks on the value computed by np.mean(y_train_7==1), converted to text, followed by a percent sign; that value summarizes how often the target in the training set indicates an increase. Using equality (==1) creates a list of True/False flags saying “did the price go up?” for each sample, and a key concept is that True/False can be treated as 1/0 so taking their mean gives the proportion that are True.

The second line does the same announcement for the test set, so you can compare whether your model will see a similar balance of up-days in evaluation as it did in learning. The print calls are like calling out the counts on a scoreboard, the equality checks are like flipping a yes/no coin for each day, and np.mean is the simple averaging step that turns those yes/no flips into a single percentage-like number. If you want an actual percent, you could multiply by 100, but as written it’s the fractional bias with a percent sign. Knowing these proportions helps you spot class imbalance before feeding data into your LSTM, which matters for fair stock-price forecasting.

Start by collecting the price data and putting it into a tidy DataFrame, which is just a smart table where rows are dates and columns are prices or indicators. Having a clean table makes later steps predictable and easier to debug.

Clean the data by filling or dropping missing values and making sure the time order is correct. Time order matters because LSTM is a sequence model that learns patterns over time, so shuffled data would break those patterns.

Scale the numbers using normalization, which just means shrinking values to a smaller range so the model learns faster and more reliably. You’ll need to remember to reverse this scaling when you turn predictions back into real prices.

Turn the time series into sequences: make short windows of past prices that the model will use to predict the next price. This prepares the data in the format an LSTM expects — a sequence-in, sequence-out setup.

Split into training and test sets, keeping the time split (no random shuffle) so the model is always tested on future data it hasn’t seen. That gives you a realistic sense of how it will perform live.

Build an LSTM model, a kind of neural network that remembers order and trends. Train it over several epochs, where each epoch is one full pass through the training data, and watch validation performance to avoid overfitting.

Evaluate with meaningful metrics like RMSE, which tells you the average error in price units, and visualize predictions against real prices to spot patterns or systematic mistakes. Finally, save the model and the scaler so you can load them to make future forecasts without repeating training.

First, gather your price data and put it into a table-like structure called a *DataFrame*, which is just a smart table that makes columns and rows easy to work with. This step matters because clean, well-organized data is the base for every later step.

Next, clean and engineer features like moving averages or volume, and fill or drop missing values so the model sees reliable signals. Feature choices help the model focus on useful patterns instead of noise.

Scale the numbers so they live in a similar range; this is called normalization and it helps neural networks learn faster and more stably. Think of it like making sure all inputs speak the same language.

Convert the sequence of prices into overlapping windows the LSTM can learn from, where each window is a small time series and the LSTM predicts the next value. Creating these windows teaches the model about how past values relate to the next one.

Split data into training and testing sets so you can check if the model actually generalizes to new data; this avoids cheating by testing on what the model has already seen. Use time-aware splitting so future data never leaks into the past.

Build and train an *LSTM* (a neural network that remembers sequences over time) and monitor validation loss to avoid overfitting, which is when a model memorizes instead of learns. Early stopping or regularization keeps the model useful on new data.

After training, transform predictions back to the original scale and compare them to real prices using simple metrics like MAE or RMSE to see how far off you are on average. Visualize predictions vs actuals to spot patterns the numbers might hide.

Walk-forward cross-validation is a way to split time-ordered data for training and validation. A *cross-validator* here just gives you which row numbers (indices) go into the training set and which go into the development (dev) or validation set. This matters for things like daily stock prices, where each sample happens at a fixed time interval.

In every split the validation set always comes later in time than the training set — its indices are higher. You can’t shuffle the rows randomly because that would mix future data into the past and let the model “peek” at what it’s supposed to predict. Keeping the order protects against that kind of leakage.

We use walk-forward splitting for forecasting with LSTMs because it mimics real forecasting: you train on past data and then test on data that actually comes later. This also helps you see whether the model stays reliable as time moves forward. The usual diagram shows a series of train windows that step forward, each followed by a later validation window.

# Time Series Split

dev_size=0.1

n_splits=int((1//dev_size)-1) # using // for integer division

tscv=TimeSeriesSplit(n_splits=n_splits) Imagine you’re setting aside a small tasting portion before you bake the whole batch: dev_size = 0.1 names that little reserved slice, so 10% of the timeline will act as the development (validation) portion. Next we try to figure out how many times we can peel off that development slice as we walk forward through history: n_splits = int((1//dev_size)-1) attempts to divide the whole (1.0) by the dev slice size and then subtract one to leave room for rolling training windows. A subtle point: using // performs floor division (with floating-point quirks it may round down unexpectedly), and int(…) makes sure we end up with an integer count of folds. Finally, tscv = TimeSeriesSplit(n_splits=n_splits) constructs the splitter that hands you a series of training/validation pairs over time. TimeSeriesSplit makes folds that respect temporal order so the model never “looks into the future” when validating. Think of the splitter as a slow curtain that reveals more past data to the model at each step, just like repeating a recipe with progressively longer ingredient lists. Together these lines reserve a validation slice size, convert that into a sensible number of rolling experiments, and create the mechanism to generate those ordered train/validation pairs — essential groundwork before you feed sequences into your LSTM to forecast stock prices.

Scaling means changing your numbers so they sit on a similar scale. Neural nets like LSTM learn faster and more reliably when inputs aren’t wildly different in size — for example, when one feature is in millions and another is between 0 and 1. This step helps gradients behave and prevents one feature from dominating the learning.

Standardization subtracts the mean and divides by the standard deviation, so data ends up with *zero mean and unit variance*. That’s useful when you want values centered and spread out based on their natural variability. Normalization (or min–max scaling) rescales values to a fixed range, usually 0 to 1, which is handy when your network prefers bounded inputs. Choose based on your model and data; many practitioners use min–max for stock prices because it keeps inputs within a predictable range.

Always fit your scaler only on the training set and then apply it to validation and test sets. Fitting on all data leaks future information into training and gives misleading performance. Save the fitted scaler so you can *inverse transform* model outputs back to original price units; otherwise your predicted numbers won’t be interpretable as real stock prices.

Scale both features and the target price if your model predicts scaled values, and apply the exact same transformation every time. This keeps training, evaluation, and live predictions consistent and makes the final results meaningful for decisions.

Always split your data before any preprocessing. Cross-validation splitting must happen first because any operation that *extracts knowledge* (like computing a mean for scaling) should only see the training data. Treat cross-validation as the outermost loop so you don’t accidentally leak information from the test folds and get an overly optimistic score.

The Pipeline class in scikit-learn is a way to glue several processing steps into one object. It has fit, predict and score methods and behaves like any other model, so you can treat the whole chain as a single estimator. A common use is to chain preprocessing (like scaling, which adjusts feature ranges) with a model so the same transforms are applied consistently during training and evaluation.

For time series we often use Walk-Forward CV, which rolls the training window forward in time. In each split the scaler (the thing that computes and applies scaling) is refit only on the sub-training split. This prevents the future (validation/test) data from influencing the scaler and thus avoids data leakage; think of it as only learning from the past.

The preprocessing flow is: first split into TRAIN and VALID according to the cv parameter in GridSearchCV or RandomizedSearchCV (cv tells how to split during hyperparameter search). Fit the scaler on TRAIN, transform TRAIN, and train models on that transformed TRAIN. Then transform VALID with that scaler and predict on the transformed VALID.

After hyperparameter selection, fit the scaler on TRAIN+VALID and transform them, then train the final model using the best parameters from Walk-Forward CV. Finally transform TEST with the scaler and predict on TEST. This gives the final model more data to learn from while keeping the test set untouched until the end.

Regularization means adding a small penalty to the weights of your baseline model so it can’t wander too freely. This makes the model less likely to learn random noise from the training data and helps it generalize*— that is, do better on new stock-price data instead of just the past data.

L2 regularization (called Ridge) adds a penalty equal to the sum of the squared weights. That pushes weights to be relatively small, and the stronger the penalty the smaller and more stable the weights become. The penalty strength, lambda, is a single number you should choose with walk‑forward cross‑validation — a rolling validation that respects time order so you don’t peek into the future.

L1 regularization (called Lasso) adds a penalty equal to the sum of the absolute values of the weights. That tends to shrink some weights exactly to zero, so some inputs stop contributing at all — in other words, it can act like automatic feature selection. As with L2, lambda is learned with walk‑forward cross‑validation; this is handy when you want to find which lagged prices or indicators really matter.

Elastic Net mixes L1 and L2 penalties so you get a bit of both behaviors. It uses lambda for overall strength and alpha to set the balance between L1 and L2. This gives a middle ground: you still cut weights, but less abruptly than Lasso, which is useful when predictors are correlated or you want both shrinkage and some selection.

A “Configuration Baseline Models” step just means you set up simple reference models to compare against your LSTM. A baseline model is a basic method that gives a quick, honest guess — for example a persistence model that says tomorrow’s price will equal today’s price, or a moving average that smooths recent prices. LSTM is a kind of neural network that learns from sequences, like a series of past prices, so baselines show whether the complex model really adds value.

When you configure these baselines you pick things like how many past days to use (window size), whether to scale prices to a smaller range, and which error measure to report. Scaling means making numbers easier for models to handle. Error measures like MSE (mean squared error) or MAE (mean absolute error) tell you how far predictions stray from real prices. Getting these settings right makes the comparison fair and prepares you to judge if the LSTM truly improves forecasts.

# Standardized Data

steps_b=[(’scaler’, StandardScaler(copy=True, with_mean=True, with_std=True)),

(’logistic’, linear_model.SGDClassifier(loss=”log”, shuffle=False, early_stopping=False, tol=1e-3, random_state=1))]

#Normalized Data

#steps_b=[(’scaler’, MinMaxScaler(feature_range=(0, 1), copy=True)),

# (’logistic’, linear_model.SGDClassifier(loss=”log”, shuffle=False, early_stopping=False, tol=1e-3, random_state=1))]

pipeline_b=Pipeline(steps_b) # Using a pipeline we glue together the Scaler & the Classifier

# This ensure that during cross validation the Scaler is fitted to only the training folds

# Penalties

penalty_b=[’l1’, ‘l2’, ‘elasticnet’]

# Evaluation Metric

scoring_b={’AUC’: ‘roc_auc’, ‘accuracy’: make_scorer(accuracy_score)} #multiple evaluation metrics

metric_b=’accuracy’ #scorer is used to find the best parameters for refitting the estimator at the endImagine we’re building a small factory that takes price features, tidies them up, and then decides if the next move is up or down — each line here wires one machine into that factory. First we define a pair of steps: a StandardScaler that centers features to zero mean and unit variance (key concept: scaling prevents features with large ranges from dominating learning), followed by an SGDClassifier set to “log” loss so it behaves like logistic regression trained with stochastic gradient descent; the classifier arguments (no shuffle, no early stopping, tolerance and a random seed) control how the optimizer searches for a solution and keep results reproducible.

We also show an alternative scaler commented out, MinMaxScaler, which rescales features into a fixed 0–1 band — think of it as a different way to normalize ingredient sizes before mixing. The Pipeline line glues the scaler and classifier into one reusable recipe card; importantly, this avoids data leakage during cross-validation by fitting the scaler only on each training fold (key concept: data leakage leads to over-optimistic performance).

Penalties lists the regularization strategies we’ll try: l1, l2, and elasticnet, which are ways to discourage overfitting by shrinking or selecting weights. scoring_b defines multiple evaluation metrics we care about — AUC and accuracy — using roc_auc and a wrapped accuracy scorer, while metric_b selects ‘accuracy’ as the primary scorer used to pick the best parameters when refitting the estimator.

All together, these lines set up a disciplined experiment to preprocess, regularize, and evaluate a classifier, a useful baseline or feature-check before you feed signals into your LSTM forecasting pipeline.

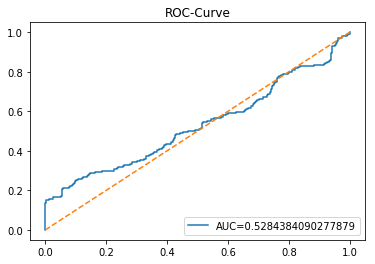

Configuring an LSTM model means choosing the settings that control how it learns to predict stock prices. An LSTM is a type of neural network that remembers patterns over time, so these choices shape how well it captures market rhythms. Good configuration matters because stock data is noisy and easy to overfit.

Decide on a sequence length (how many past time steps the model sees), batch size (how many examples it learns from at once), number of epochs (how many times it looks through the data), and learning rate (how big each update is). Typical sequence lengths are days to weeks, batch sizes are tens to hundreds, and the learning rate is small (e.g., 0.001). These control memory, speed, and stability during training.

Choose the model architecture: one or more LSTM layers with a set number of units (neurons), optional dropout (randomly ignoring some neurons to prevent overfitting), and a final dense output layer for the price. Use a regression loss like mean squared error (MSE) because we predict continuous prices, and an optimizer like Adam to adjust weights. Add early stopping and checkpoints to save the best model and avoid training too long.

Preprocess your data by scaling prices (e.g., MinMax scaling) because neural nets learn better on similar-sized numbers. Split into train and test sets, and convert series into sequences with the chosen window. You can add extra features like volume or indicators, which often improves forecasts. Save the configuration so you can reproduce or tune experiments later.

# Batch_input_shape=[1, 1, Z] -> (batch size, time steps, number of features)

# Data set inputs(trainX)=[X, 1, Z] -> (samples, time steps, number of features)

# number of samples

num_samples=1

# time_steps

look_back=1

# Evaluation Metric

scoring_lstm=’accuracy’ Imagine we’re assembling a tiny kitchen to teach a model how past prices predict the next one. The first two comment lines set the shapes of the ingredients: Batch_input_shape=[1, 1, Z] is saying we will feed the LSTM one mini-batch at a time (batch size 1), each batch containing one time step, and Z different features per time step — think of batch size as how many identical dishes you cook at once, time steps as how many consecutive days of prices you put into the pot, and features as the different ingredients like open, high, low, volume. The dataset inputs line maps samples to the recipe count: Data set inputs(trainX)=[X, 1, Z] means you have X examples (samples), each example is a single time step with Z features.

Setting num_samples = 1 names how many examples you’re currently treating as a unit; it’s the count of recipes on your counter. look_back = 1 chooses how many previous time steps the model looks back — a look-back of 1 means the model uses one prior moment to predict the next, like consulting only yesterday’s price. The variable scoring_lstm = ‘accuracy’ picks the performance metric: accuracy measures how often a categorical prediction exactly matches the label, and as a key concept, metrics must match the task — for continuous forecasting you’d usually prefer mean squared error rather than accuracy.

All together these lines establish the input geometry and evaluation lens for the LSTM kitchen; getting shapes and metrics right is essential before you bake forecasts for stock prices.

This is section 6, Models. Here we build the pieces that actually learn from past prices and try to predict future stock values.

We’ll mainly use LSTM models — an LSTM is a kind of neural network that remembers patterns over time, like how recent prices and trends affect what comes next. We train the model on historical data so it learns those patterns, then test it on new data to see how well it forecasts. This step matters because a model that understands time patterns can give more realistic predictions than one that looks at each day by itself.

We’ll also compare settings like how many memory cells the LSTM has, how long of a price history we feed it, and how many training passes we run. These choices — called hyperparameters — shape how well the model learns and how quickly it runs. Trying different options helps us find a balance between accurate forecasts and a model that’s practical to use.

This model predicts volatility, which is just how much a stock’s price swings up and down over time. Volatility matters because it helps you understand risk and make safer forecasts — sometimes predicting volatility is easier and more useful than predicting the exact price.

We first turn prices into returns, which are the percentage or *log* changes from one day to the next — a simple way to compare moves. Then we compute a rolling standard deviation over a short window to get realized volatility; a rolling window just means we look at the last N days each time. This gives a smoother series that an LSTM can learn from.

An LSTM is a kind of neural network that remembers patterns in sequences, like past volatility values, so it can predict the next one. We feed the model sequences of recent volatility, scale the numbers so the network trains well, and keep the time order when we split into training and test sets (don’t shuffle time series data — that would leak the future into the past).

We train with a regression loss like mean squared error and watch validation error for early stopping, which prevents overfitting by stopping when the model stops improving. Evaluating with RMSE or similar measures tells you how close predicted volatility is to actual volatility, and that helps decide if the model is ready to support trading or risk decisions.

A baseline is just a simple, easy-to-understand method we use as a reference point. Think of it as the score you must beat — a basic rule of thumb that any fancy model should outperform.

Common baselines for stock forecasting are very simple: predict that tomorrow’s price equals today’s price, or use a short moving average (which is just the average of the last few prices). These are easy to run and explain, and they give you a quick sense of how hard the task really is.

You’ll compare your LSTM’s errors (like mean absolute error) against the baseline’s errors to see if the LSTM actually learns useful patterns. This step helps catch models that look complex but don’t improve on trivial rules, and it sets a realistic performance goal before you fine-tune the LSTM.

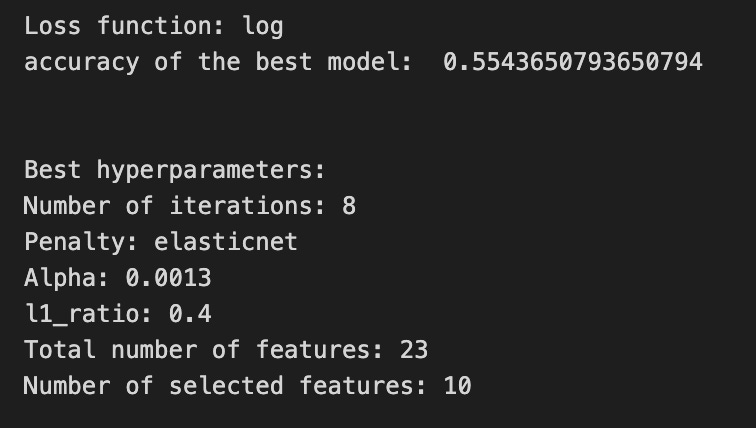

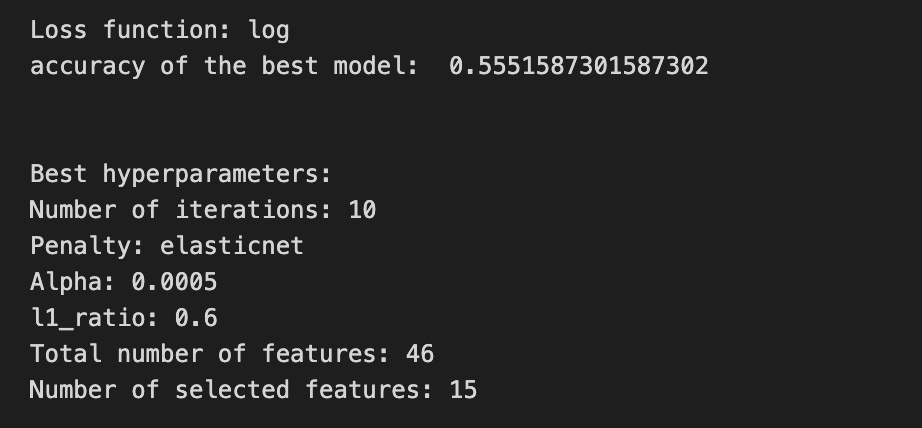

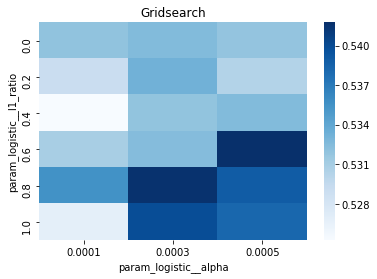

# Model specific Parameter

# Number of iterations

iterations_1_b=[8]

# Grid Search

# Regularization

alpha_g_1_b=[0.0011, 0.0013, 0.0014] #0.0011, 0.0012, 0.0013

l1_ratio_g_1_b=[0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1]

# Create hyperparameter options

hyperparameters_g_1_b={’logistic__alpha’:alpha_g_1_b,

‘logistic__l1_ratio’:l1_ratio_g_1_b,

‘logistic__penalty’:penalty_b,

‘logistic__max_iter’:iterations_1_b}

# Create grid search

search_g_1_b=GridSearchCV(estimator=pipeline_b,

param_grid=hyperparameters_g_1_b,

cv=tscv,

verbose=0,

n_jobs=-1,

scoring=scoring_b,

refit=metric_b,

return_train_score=False)

# Setting refit=’Accuracy’, refits an estimator on the whole dataset with the parameter setting that has the best cross-validated mean Accuracy score.

# For multiple metric evaluation, this needs to be a string denoting the scorer is used to find the best parameters for refitting the estimator at the end

# If return_train_score=True training results of CV will be saved as well

# Fit grid search

tuned_model_1_b=search_g_1_b.fit(X_train_1, y_train_1)

#search_g_1_b.cv_results_

# Random Search

# Create regularization hyperparameter distribution using uniform distribution

#alpha_r_1_b=uniform(loc=0.00006, scale=0.002)

#l1_ratio_r_1_b=uniform(loc=0, scale=1)

# Create hyperparameter options

#hyperparameters_r_1_b={’logistic__alpha’:alpha_r_1_b, ‘logistic__l1_ratio’:l1_ratio_r_1_b, ‘logistic__penalty’:penalty_b,’logistic__max_iter’:iterations_1_b}

# Create randomized search

#search_r_1_b=RandomizedSearchCV(pipeline_b,

# hyperparameters_r_1_b,

# n_iter=10,

# random_state=1,

# cv=tscv,

# verbose=0,

# n_jobs=-1,

# scoring=scoring_b,

# refit=metric_b,

# return_train_score=True)

# Setting refit=’Accuracy’, refits an estimator on the whole dataset with the parameter setting that has the best cross-validated Accuracy score.

# For multiple metric evaluation, this needs to be a string denoting the scorer is used to find the best parameters for refitting the estimator at the end

# If return_train_score=True training results of CV will be saved as well

# Fit randomized search

#tuned_model_1_b=search_r_1_b.fit(X_train_1, y_train_1)

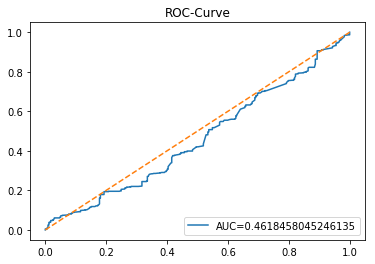

# View Cost function

print(’Loss function:’, tuned_model_1_b.best_estimator_.get_params()[’logistic__loss’])

# View Accuracy

print(metric_b +’ of the best model: ‘, tuned_model_1_b.best_score_);print(”\n”)

# best_score_ Mean cross-validated score of the best_estimator

# View best hyperparameters

print(”Best hyperparameters:”)

print(’Number of iterations:’, tuned_model_1_b.best_estimator_.get_params()[’logistic__max_iter’])

print(’Penalty:’, tuned_model_1_b.best_estimator_.get_params()[’logistic__penalty’])

print(’Alpha:’, tuned_model_1_b.best_estimator_.get_params()[’logistic__alpha’])

print(’l1_ratio:’, tuned_model_1_b.best_estimator_.get_params()[’logistic__l1_ratio’])

# Find the number of nonzero coefficients (selected features)

print(”Total number of features:”, len(tuned_model_1_b.best_estimator_.steps[1][1].coef_[0][:]))

print(”Number of selected features:”, np.count_nonzero(tuned_model_1_b.best_estimator_.steps[1][1].coef_[0][:]))

# Gridsearch table

plt.title(’Gridsearch’)

pvt_1_b=pd.pivot_table(pd.DataFrame(tuned_model_1_b.cv_results_), values=’mean_test_accuracy’, index=’param_logistic__l1_ratio’, columns=’param_logistic__alpha’)

ax_1_b=sns.heatmap(pvt_1_b, cmap=”Blues”)

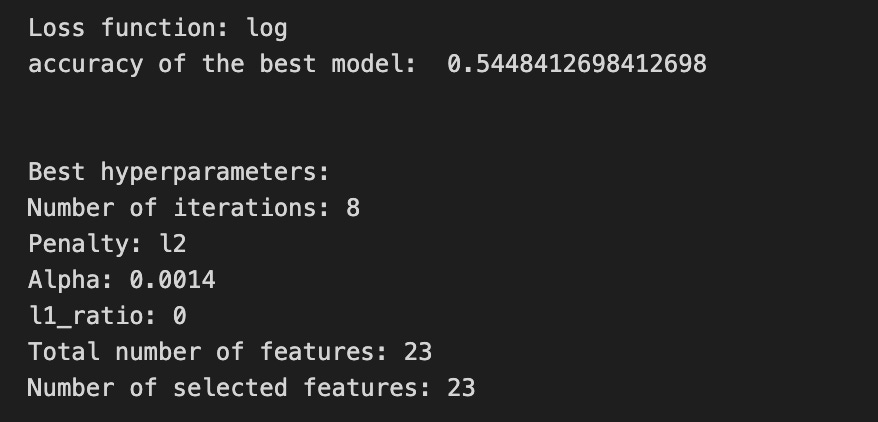

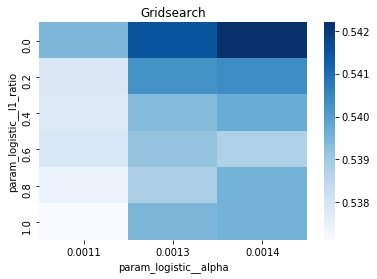

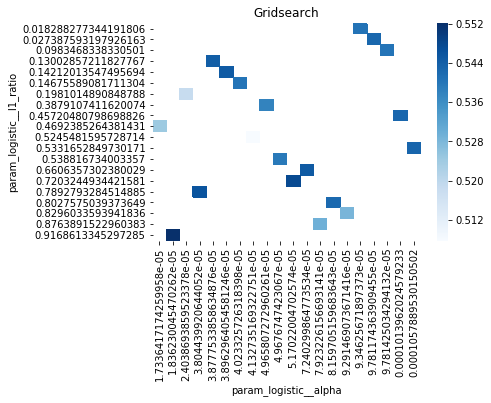

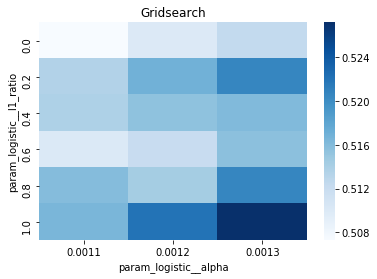

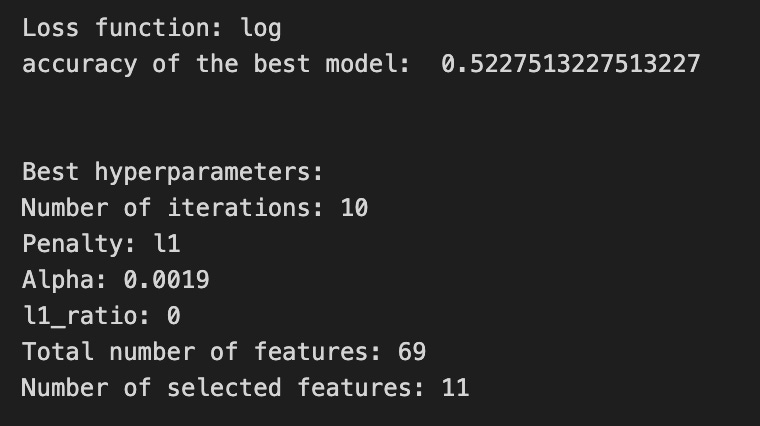

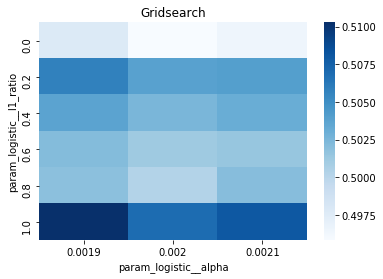

plt.show()We’re trying to find the best settings for a model so it will generalize well to future stock movements, and the first line sets a small list of allowed solver iterations like writing “try up to 8 steps” on a recipe card (iterations_1_b = [8]). The next two lines set up candidate strengths and mixes of regularization (alpha and l1_ratio), which control how aggressively we shrink coefficients to avoid overfitting — regularization is like putting a leash on model complexity. Those lists are gathered into a hyperparameter dictionary keyed for the pipeline’s logistic step, so the grid knows which knobs to turn.

GridSearchCV is created next: it is the systematic tasting session that tries every combination, using tscv for time-aware cross-validation (time-series cross-validation preserves temporal order so we validate like we would predict forward). Scoring and refit tell the search how to judge and which metric to use to refit the final model. The fit call runs the whole tasting session on X_train_1 and y_train_1 and gives back tuned_model_1_b.

A randomized search appears commented out as an alternative tasting method that samples from continuous distributions rather than exhaustively checking a grid. After fitting, we inspect the winner: we print the chosen loss, the best cross-validated score, and the selected hyperparameters (iterations, penalty, alpha, l1_ratio) by asking the final estimator for its parameters. We then count total and nonzero coefficients to see how many features survived the regularization — nonzero count shows selected features. Finally we build a pivot table of mean test accuracy over l1_ratio and alpha and draw a heatmap so we can visually spot the sweet spot, like mapping which spice combo worked best. All of these tuning and validation steps are the same careful craft you’ll need when tuning an LSTM for stock-price forecasting.

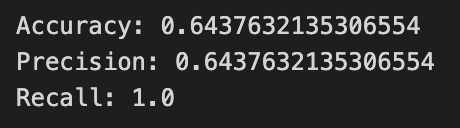

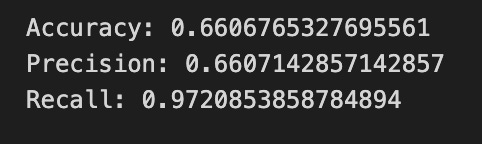

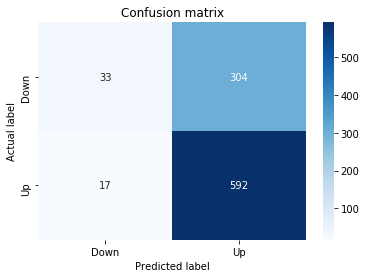

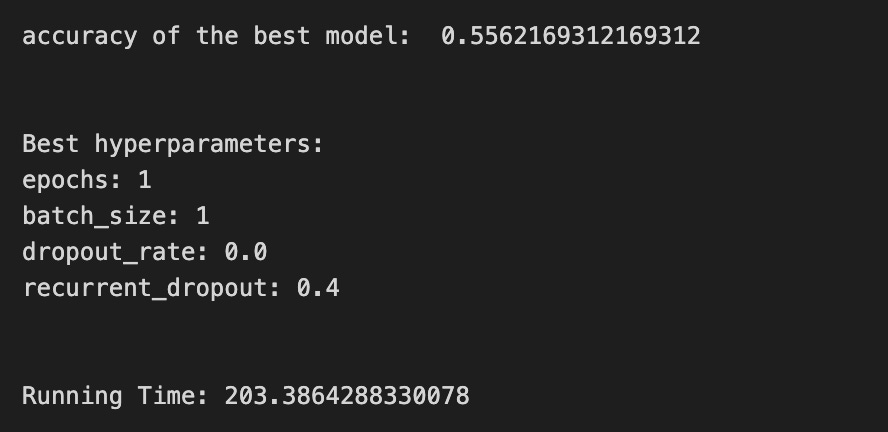

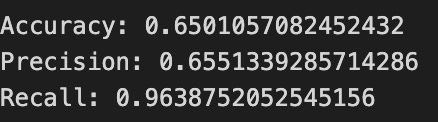

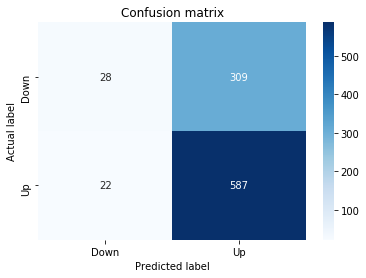

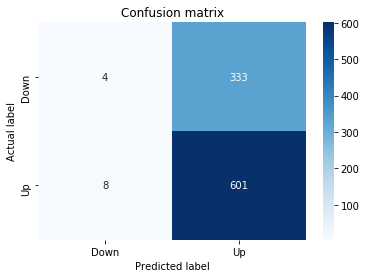

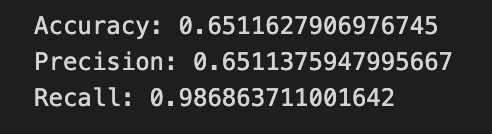

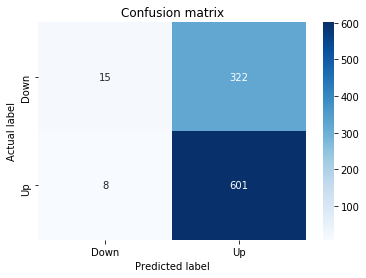

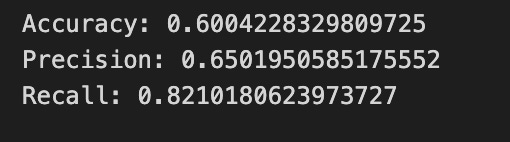

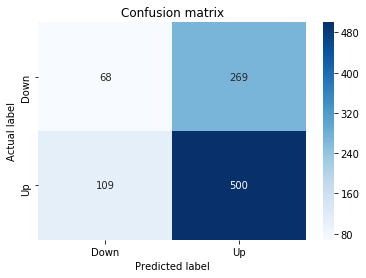

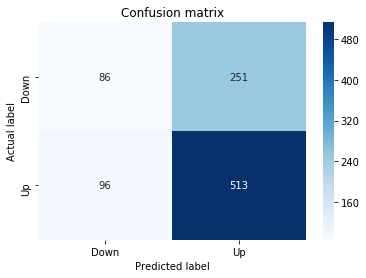

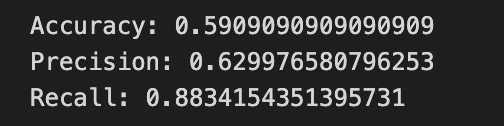

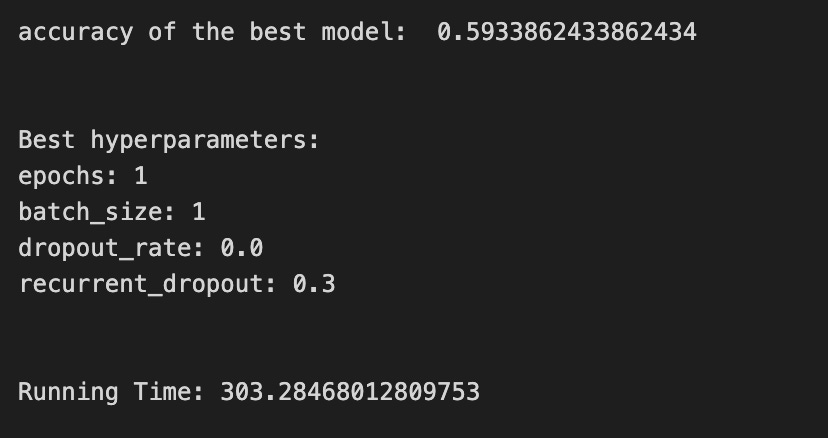

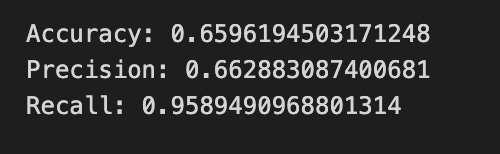

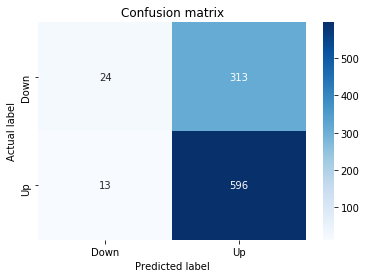

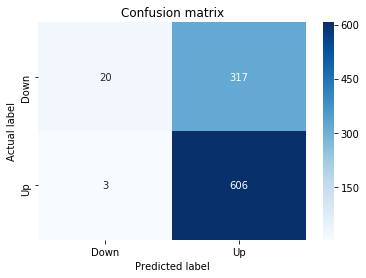

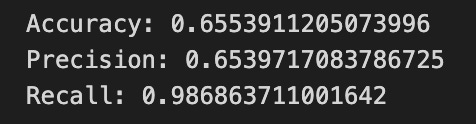

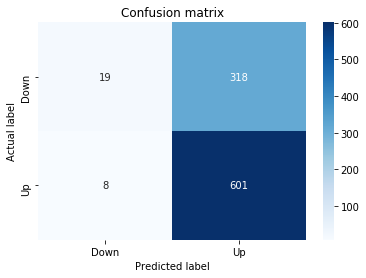

A confusion matrix is just a small table that shows how often your model’s predictions match the real outcomes. It compares what you predicted (like “price will go up”) with what actually happened (price up or down), so you can see every kind of right and wrong at a glance. This is useful when you turn a continuous price forecast into categories like “up” or “down.”

The table has four cells: true positives (predicted up and it was up), true negatives (predicted down and it was down), false positives (predicted up but it fell), and false negatives (predicted down but it rose). Saying each name this way keeps the meaning clear and helps you spot which mistakes happen most.

Looking at a confusion matrix helps you decide what to fix — maybe your model predicts ups well but misses downs, or vice versa. You can then compute accuracy and other measures, or weigh mistakes differently if some errors cost more in trading. For stock forecasting, that context matters because the type of error can affect strategy and risk.

# Make predictions

y_pred_1_b=tuned_model_1_b.predict(X_test_1)

# create confustion matrix

fig, ax=plt.subplots()

sns.heatmap(pd.DataFrame(metrics.confusion_matrix(y_test_1, y_pred_1_b)), annot=True, cmap=”Blues” ,fmt=’g’)

plt.title(’Confusion matrix’); plt.ylabel(’Actual label’); plt.xlabel(’Predicted label’)

ax.xaxis.set_ticklabels([’Down’, ‘Up’]); ax.yaxis.set_ticklabels([’Down’, ‘Up’])

print(”Accuracy:”,metrics.accuracy_score(y_test_1, y_pred_1_b))

print(”Precision:”,metrics.precision_score(y_test_1, y_pred_1_b))

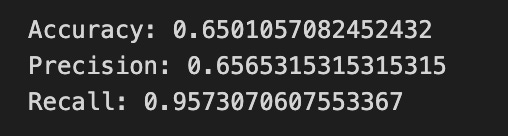

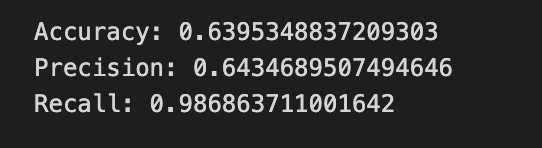

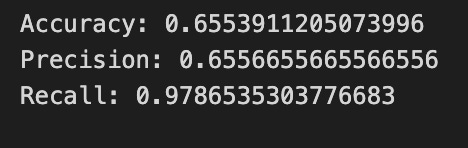

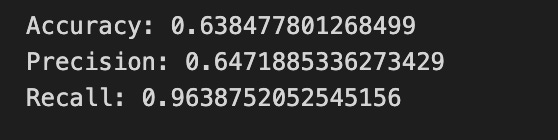

print(”Recall:”,metrics.recall_score(y_test_1, y_pred_1_b))Now we ask our tuned LSTM to tell us what it thinks will happen: the predict call applies the model’s learned patterns to each test example and returns a predicted direction for each day. Key concept: prediction means the model uses its learned weights to map inputs to output labels or probabilities.

Next we build a picture of how well those predictions match reality by drawing a confusion matrix; creating the figure and axes gives us a blank canvas to paint on, and the heatmap plots the matrix of counts so you can see at a glance where the model is right or wrong. Key concept: a confusion matrix shows the counts of true vs predicted classes so you can inspect types of errors.

We then add a title and axis labels so the picture is readable, and replace the numeric tick labels with “Down” and “Up” to make the axes speak the language of stock moves rather than abstract indices.

Finally we print three summary scores that quantify performance: accuracy is the fraction of all days the model classified correctly, precision tells you of the days the model predicted “Up” how many were actually up (useful when false positives are costly), and recall measures of the actual up-days how many the model captured (important when missing an up move is costly). Key concept: these metrics each emphasize different error trade-offs.

Together, the visual confusion matrix and these metrics help you judge whether the model’s direction forecasts are reliable enough to inform trading or further model tuning.

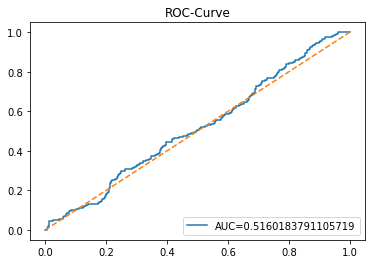

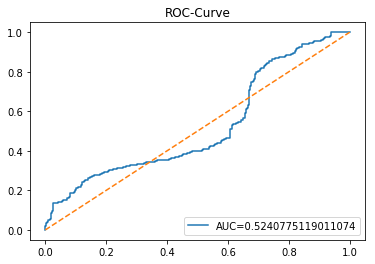

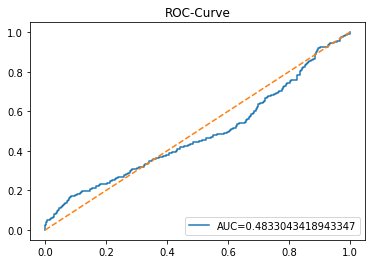

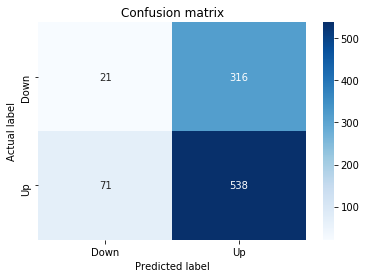

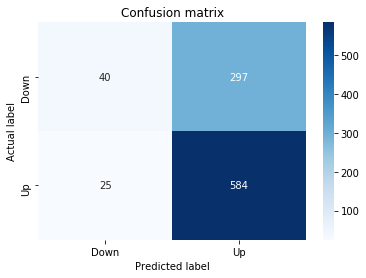

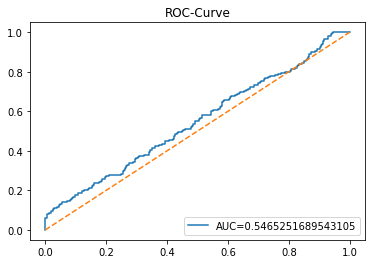

The ROC curve is a simple picture that shows how well a binary predictor separates two classes. In stock forecasting that usually means predicting “price up” vs “price down.” It plots the true positive rate (the share of actual ups you caught) against the false positive rate (the share of downs you mistakenly called ups) as you change the decision threshold.