Engineering a Stock Prediction Pipeline: Building a Robust Trading Pipeline with Python and TA-Lib

Master the art of data preparation, outlier removal, and signal generation for quantitative strategies.

Download source code link at the end of the article:

There are some issues with displaying images in certain articles. I’m aware of the problem and currently working to fix it. In the meantime, you can view the complete output and all the charts in the Jupyter notebook.

Success in algorithmic trading relies less on finding a “magic algorithm” and more on the quality of the pipeline that feeds it. Raw market data is inherently noisy and unstructured, making it unsuitable for direct modeling without rigorous preprocessing. This guide provides a practical, code-first approach to constructing a production-grade trading workflow. We will walk through the essential stages of data ingestion, cleaning, and outlier removal, before utilizing TA-Lib to engineer powerful alpha factors — transforming raw price action into robust, actionable signals for your quantitative strategies.

import warnings

warnings.filterwarnings(’ignore’)Those two lines globally silence all Python warning messages for the running process. In practice, the warnings module is used by libraries to emit non-fatal alerts — deprecation notices, numerical stability hints, performance suggestions, or environment/configuration issues — and calling filterwarnings(‘ignore’) disables every such warning emitted after that point across all modules. The immediate effect is a much cleaner console or log output, which is often why teams put this at the top of notebooks or quick backtests to reduce noise.

In an algorithmic trading codebase, the intent is usually to avoid flooding logs with repetitive, benign messages from dependencies (e.g., deprecated API calls in a plotting library, or benign dtype coercions in pandas) so that you and other engineers can focus on important runtime information like order execution logs, slippage, and exceptions. That can be valuable during exploratory analysis or when generating human-facing reports where warning clutter obscures core output.

However, silencing all warnings is risky in a trading context because warnings are early indicators of issues that can materially affect strategy behavior and P&L. Deprecation warnings can hide forthcoming API changes that will break live trading; numerical or precision warnings from NumPy/Pandas/TA libraries can signal stability problems in indicators; resource or threading warnings may flag concurrency issues that manifest under production load. Because filterwarnings(‘ignore’) is global and permanent for the process, it can mask these signals and make bugs harder to find or lead to silent misbehavior.

A safer approach is to be intentional about which warnings to suppress: restrict suppression to specific warning categories, modules, or message patterns and do it only around the code that is known to generate benign noise. Another good pattern is to capture warnings and route them into structured logs (so they’re suppressed on stdout but still recorded), or to use temporary warning filters scoped to a particular block when you’re calling a noisy third-party routine during backtests. In short, prefer targeted filtering and persistent recording of warnings over a blanket ignore; that preserves the cleanliness of your output while keeping important diagnostic signals available for monitoring, debugging, and risk management.

%matplotlib inline

from pathlib import Path

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as snsThis small setup block is doing the standard environment preparation for a notebook-based algorithmic trading workflow: it chooses an inline plotting backend for immediate visual feedback and imports the core libraries we’ll use to ingest, transform, analyze, and visualize time-series market data. In practice the data flow starts with Pathlib objects to locate CSVs or other data artifacts robustly across environments — we prefer Path over plain strings because it centralizes path manipulations (joining, resolving, checking existence) and reduces platform-specific bugs when loading historical ticks, bars, or other datasets used by strategies and backtests.

Pandas and NumPy form the computational backbone. We use pandas to represent market data as time-indexed DataFrames (OHLCV, ticks, signal columns), because pandas makes resampling, alignment, timezone handling, and missing-value propagation straightforward. NumPy is used where performance matters: indicator calculations and vectorized signal logic should operate on NumPy arrays (or pandas Series backed by NumPy) to avoid Python-level loops during backtests. This combination lets us compute moving averages, rolling volatility, returns, and other features efficiently while keeping the code readable and easy to align with timestamps.

Matplotlib and Seaborn are included for visualization: matplotlib gives precise control needed to render price series, overlay indicators, and annotate entry/exit markers that are critical for manual verification of strategy behavior, while Seaborn provides higher-level statistical plotting and polished styles (heatmaps for correlation matrices, distribution plots for returns, pairwise feature inspections) that help diagnose overfitting, feature redundancy, or regime changes. Using the notebook inline backend is intentional for iterative development: you can inspect charts and intermediate outputs immediately as you tune signals. For production backtests or automated runs, we typically switch to a non-interactive backend and save figures to files to avoid blocking execution.

Operationally, this setup encourages a workflow: locate and load data via Path -> read into pandas DataFrame -> normalize/clean timestamps and missing data -> compute features with NumPy-backed vectorized operations -> generate signals and perform backtests -> visualize outcomes with matplotlib/seaborn to validate hypothesis and inspect edge cases. A couple of practical notes tied to algorithmic trading: prefer vectorized implementations to keep backtest runtime reasonable, be explicit about datetime/timezone handling to avoid subtle alignment bugs across exchanges, and reserve seaborn/matplotlib styling in exploratory phases while exporting deterministic plots for reports or CI runs.

sns.set_style(’whitegrid’)

idx = pd.IndexSlice

deciles = np.arange(.1, 1, .1).round(1)The first line, sns.set_style(‘whitegrid’), is a global plotting configuration: it switches seaborn/matplotlib to a clean, light background with subtle gridlines. In the context of algorithmic trading this is a deliberate choice to make time-series, cumulative P&L and cross-sectional comparison plots easier to read — gridlines help the viewer judge levels and slopes quickly when inspecting.strategy performance, drawdowns or factor exposures. Setting the style once up front ensures all subsequent plots are visually consistent for reporting and debugging.

The second line, idx = pd.IndexSlice, is a small convenience assignment for working with pandas MultiIndex objects. In trading code you typically have hierarchical indices (for example date × asset, or date × portfolio bucket) and you frequently need to select cross-sections for rebalancing, computing returns, or aggregating metrics. IndexSlice lets you write expressive loc-indexing like df.loc[idx[:, ‘AAPL’], :] or df.loc[idx[date_slice, :], [‘weight’,’return’]] rather than composing tuples manually. Assigning it to the name idx is purely for brevity and readability in the downstream selection logic that follows.

The third line, deciles = np.arange(.1, 1, .1).round(1), constructs the numeric cutpoints for decile-based bucketing: it produces [0.1, 0.2, …, 0.9]. These values are typically used to form quantile bins (e.g., with pandas.qcut or to compute percentile thresholds) so you can build decile portfolios, measure decile-level returns, or form long-short spreads between top and bottom buckets. The use of np.arange with a small step can introduce floating-point imprecision, so the .round(1) is intentional: it normalizes the cutpoints to one decimal place to avoid subtle mismatches when comparing or labeling buckets and to make later joins/labels deterministic. In short, this line prepares the canonical decile boundaries that downstream logic will use to discretize continuous signals into portfolio buckets for performance attribution and risk control.

Loading Data

DATA_STORE = Path(’..’, ‘data’, ‘assets.h5’)This single line declares a single, central reference to the on-disk asset store used throughout the trading codebase. By assigning a Path object to the uppercase name DATA_STORE we create an explicit, canonical handle for the HDF5 file that contains historical price/volume series, instrument metadata, and any precomputed features or aggregated windows. Using Pathlib instead of a bare string gives us cross‑platform path manipulation and convenient file operations (exists(), open(), etc.), and the HDF5 extension (.h5) signals that the file is a binary, columnar container (typically accessed via pandas.HDFStore or PyTables) which is chosen because it supports compact storage, compression, and efficient partial reads of large time series without materializing everything into memory — an important property for backtests and live-feeds in algorithmic trading.

Placing the file under a relative ../data location reflects a deliberate separation of code and data: keep large, frequently changing datasets out of the repository, and allow the data directory to be mounted or replaced in different environments (development, CI, production). The constant name (uppercase) makes it a single source of truth for all modules that need to load or persist market data, reducing the chance of hard-coded paths scattered through the codebase.

A few design and operational considerations inform this choice. HDF5 is excellent for read-heavy workflows and for efficient slicing by time/instrument, which aligns with how backtests and feature pipelines operate; however, HDF5 has limitations for concurrent writes and heavy multi-process access, so for high-concurrency ingestion you may prefer a database, object store with Parquet, or a write-ahead staging service. Also, relying on a relative path means the working directory matters — in production it’s safer to resolve this path or make it configurable via environment/config so deployments don’t fail due to a missing ../data folder.

In short: DATA_STORE centralizes where historical assets live, uses Pathlib for robust filesystem handling, and signals the use of an HDF5-backed time-series store optimized for the read-heavy, memory-conscious patterns typical in algorithmic trading, while also suggesting attention to configuration and concurrency as the system scales.

with pd.HDFStore(DATA_STORE) as store:

data = (store[’quandl/wiki/prices’]

.loc[idx[’2007’:’2016’, :],

[’adj_open’, ‘adj_high’, ‘adj_low’, ‘adj_close’, ‘adj_volume’]]

.dropna()

.swaplevel()

.sort_index()

.rename(columns=lambda x: x.replace(’adj_’, ‘’)))

metadata = store[’us_equities/stocks’].loc[:, [’marketcap’, ‘sector’]]This block opens the HDF5 store and materializes two clean, usable datasets that are the starting point for downstream algorithmic-trading tasks: a per-security time series of adjusted prices and volumes, and a small table of static stock metadata. The first expression reads the stored Quandl prices table and immediately restricts it to a ten-year date window (2007–2016) for all tickers, selecting only the adjusted open/high/low/close/volume fields. That date slicing limits the historical horizon you’ll backtest over or feature-engineer from, keeping later computations bounded and reproducible.

After selecting the relevant columns the code drops any rows containing missing values. The practical reason is to ensure every timestamp used for feature generation and return calculations has a complete set of price and volume inputs; leaving NaNs in place would propagate through derived signals and could silently break rolling/aggregation logic. If you need to preserve partial records for other strategies you would choose a different cleaning strategy (e.g., per-column fill or subset-based dropping), but here the intent is a contiguous, complete sample per observation.

Next the code swaps the two index levels and sorts the index. The original table is typically indexed as (date, ticker); swapping makes the outer level ticker and the inner level date. That layout is deliberate: making ticker the primary axis simplifies common operations in trading systems such as groupby(level=’ticker’) aggregations, per-security rolling window computations, and fast selection of an individual instrument’s time series. Sorting the index after swapping enforces a stable, ascending order (ticker, then date) so time-series operations assume monotonic timestamps within each ticker — a necessary condition for correct rolling windows, forward/backward fills, and any algorithms that iterate in chronological order.

Finally, the adjusted column names are simplified by stripping the ‘adj_’ prefix so downstream code can reference familiar names like open/high/low/close/volume without repeatedly handling adjusted-vs-unadjusted logic. In parallel, the metadata line pulls the stocks table and keeps only market capitalization and sector for each ticker. That metadata is purposefully kept separate: marketcap is commonly used for universe selection or weighting schemes, and sector is used for exposure controls or grouping; keeping it as a compact lookup table reduces memory footprint and separates static attributes from the time series.

One last practical note: the HDFStore is used within a context manager to ensure the file handle is closed cleanly. Also be aware this pipeline’s use of dropna may materially reduce sample size if many tickers have intermittent missing fields — which is an intentional trade-off here to guarantee clean inputs for feature calculation and backtesting.

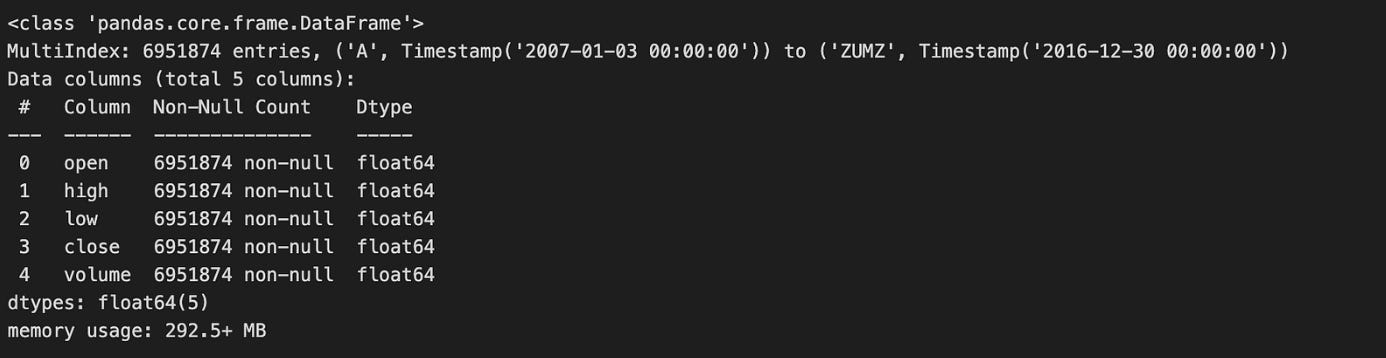

data.info(null_counts=True)Calling data.info(null_counts=True) is a quick, diagnostic step you run immediately after loading market data to get a compact summary of the table that drives subsequent preprocessing and modeling decisions. The call prints the DataFrame’s index type and range, then for each column shows its name, dtype and the number of non-null entries, and finally the approximate memory footprint. In the algorithmic trading workflow this single snapshot tells you whether key series (prices, volumes, timestamps, identifiers) are represented with appropriate dtypes (e.g., numeric vs object, datetime vs string) and how much missing data each column contains — information you need before any feature engineering, resampling, or backtest.

Why this matters: non-null counts reveal the degree and distribution of missingness that will dictate your strategy for handling gaps. For time-series fields like prices you typically prefer interpolation or forward-fill with careful edge handling to avoid look-ahead bias; for reference fields (tickers, exchange ids) you may drop rows or cast to categorical if sparse. The dtypes reported by info tell you which columns need conversion (strings -> timestamps for indexing/resampling, objects -> numeric for indicator computation), and the memory-usage figure prompts downcasting (float64 -> float32, int64 -> int32, or using categorical encoding) when working with long histories or high-frequency data to reduce RAM and speed up backtests.

A couple of practical caveats and next steps: info’s non-null counts are a useful summary but don’t show the temporal pattern of missing values (e.g., clustered gaps or leading/trailing NaNs), so follow up with targeted checks like data.isna().sum(), visual inspection of series, and index continuity checks to decide interpolation windows and alignment strategies. Also note that in recent pandas versions the null_counts parameter has been superseded by newer flags (e.g., show_counts), so you may see a deprecation warning; the conceptual goal remains the same — get an early, actionable portrait of types, missingness, and memory so you can choose safe imputation, dtype conversions, and downcasting before feeding the data into signal generation or model training.

metadata.sector = pd.factorize(metadata.sector)[0]

metadata.info()

This two-line snippet is converting the sector column from textual categories into compact integer codes and then checking the DataFrame’s schema and memory footprint. The first line replaces each distinct sector string with a small integer label returned by pandas.factorize; the function actually produces a pair — an array of integer labels and an array of the unique values — but the code only keeps the labels (index [0]) and writes them back into metadata.sector. Conceptually, this turns a high-cardinality, variable-length string column into fixed-width numeric values that are far more efficient to store and feed into downstream algorithms.

We do this because most ML models and many numerical pipelines in an algorithmic trading stack expect numeric inputs, and categorical text values would otherwise require extra preprocessing at training or inference time. Factorizing here is a quick form of label-encoding that reduces memory and speeds up joins and vectorized operations. It also makes grouping and slicing (for sector-level portfolio rules, risk aggregation, or backtesting stratification) much more straightforward and deterministic within a single run.

There are important behavioral details to keep in mind: the integer codes start at zero and are assigned in the order that unique sector values first appear in the Series, so the mapping is data-order dependent and effectively arbitrary. Nulls in the original column are encoded as -1. Because the code discards the second return value (the uniques array), it does not persist the mapping between integers and sector names — which means this transformation will not be reproducible across different datasets or runs unless you explicitly save the mapping. That becomes critical when you need the same encoding at training, backtesting, and live trading times; otherwise you can mislabel sectors and corrupt features or decision logic.

Finally, metadata.info() is being used to validate the result: it confirms the sector column’s new dtype, non-null counts, and memory usage so you can verify the conversion succeeded and see the resource impact. For production robustness, consider alternatives depending on the model and use-case: persist the factorize uniques (or build an explicit mapping) to ensure stable encodings across environments; use pandas.Categorical (or category dtype) to get a memory-efficient representation that retains category names; or choose one-hot/embedding schemes if the model would wrongly interpret integer labels as ordinal.

data = data.join(metadata).dropna(subset=[’sector’])This line first augments the primary market data with asset-level metadata, then removes any rows that lack a sector label. Concretely, data.join(metadata) attaches columns from the metadata DataFrame to the data DataFrame by aligning on their indices (the default join behavior), so each market-observation row gets its corresponding metadata fields such as sector, industry, or other static descriptors. Immediately after that, .dropna(subset=[‘sector’]) discards any resulting rows where the sector field is missing, ensuring every remaining observation has a valid sector value for downstream processing.

We do this because sector is a critical discriminator in many algorithmic-trading workflows: it drives sector-neutral factor construction, sector-based risk models, portfolio tilting logic, and group-wise feature engineering. By enforcing presence of sector early, subsequent steps can safely compute sector-relative z-scores, apply sector-specific weights, or perform cross-sectional ranking without adding conditional logic to handle missing categories. Practically, the join-first-then-drop pattern preserves the row ordering and alignment of the primary data while ensuring we eliminate records that would otherwise introduce NaNs or incorrect group assignments into models and backtests.

There are important behavioral and data-quality implications to be aware of. Because join aligns on the DataFrame index, it assumes the metadata index matches the market-data index semantics (e.g., ticker, instrument ID, or a date-ticker MultiIndex). If indexes are different — say metadata keyed by ticker while data is keyed by date — this will produce unexpected mismatches; you should make the index correspondence explicit or use merge on key columns when appropriate. Also note that join defaults to a left join: combining it with dropna on sector effectively yields the same result as an inner join on rows that have sector, but the intermediate step preserves full alignment semantics before pruning. Dropping rows may materially change the universe and introduce survivorship or selection bias if missingness is non-random, so always quantify how many rows were removed and why. Finally, ensure metadata has unique keys to avoid duplicated rows after join; if there are duplicates, they can explode the data size and corrupt time-series relationships. If missing sector labels are frequent but non-informative, consider controlled imputation or a dedicated “unknown” bucket instead of outright dropping, depending on the modelling and backtest requirements.

data.info(null_counts=True)

This single call interrogates the DataFrame’s metadata and prints a compact summary that’s meant to quickly reveal structural and cleanliness issues before any heavy algorithmic-trading work. When you run data.info(null_counts=True), pandas iterates over each column, counts non-null entries, determines the column dtype, and reports those non-null counts alongside the dtype and index range; it also prints an estimate of the DataFrame’s memory usage. The key purpose in our trading pipeline is diagnostic: the non-null counts reveal missing ticks or gaps in time-series columns that will affect resampling, windowed features, and model inputs; the dtypes flag columns that need conversion (for example, object -> datetime64 for timestamps, or object -> float for prices), and the memory-usage estimate helps decide whether to downcast numeric types or convert high-cardinality strings to categoricals before batch processing or vectorized calculations.

A few practical points that explain why we prefer this step up front: many downstream operations assume dense numeric arrays and consistent dtypes (e.g., rolling windows, vectorized indicators, or ML feature matrices), so discovering missing values or wrong dtypes early prevents subtle bugs and large, expensive type conversions later. Note that data.info prints to stdout (it doesn’t return the counts), and the non-null counts are what’s shown — true null counts are len(data) minus the reported non-null count, so if you need exact null tallies use data.isna().sum(). Also be aware that parameter names changed in recent pandas versions (null_counts was replaced by show_counts) and that memory_usage=’deep’ gives a more precise memory estimate for object columns; these refinements matter when diagnosing large tick-level datasets prior to feature engineering and model training.

print(f”# Tickers: {len(data.index.unique(’ticker’)):,.0f} | # Dates: {len(data.index.unique(’date’)):,.0f}”)

This single line is a compact sanity check that reports the two most important dimensions of a market dataset for algorithmic trading: the number of distinct instruments (tickers) and the number of distinct time points (dates) present in the index. Internally it asks the DataFrame’s index for the unique labels at the named level ‘ticker’, counts them, formats that integer with thousands separators and zero decimal places, and does the same for the named level ‘date’, then prints a one-line summary. We do this early in a pipeline so we immediately confirm the breadth of the cross-section (how many symbols we have) and the length of the time series (how many distinct dates), which are critical to downstream decisions like whether the universe is large enough for cross-sectional signals, whether there is enough history for time-series models, and whether data ingestion succeeded.

There are a few important “why” and “how” implications to keep in mind. This relies on the index being a MultiIndex with named levels ‘ticker’ and ‘date’; if those names are missing or different you’ll get an error or wrong counts, so naming and normalizing the index upstream is important. Using index.unique(…) returns each distinct label, so duplicate rows for the same ticker on different dates won’t inflate the ticker count — that’s the desired behavior when checking universe size. For dates, the unique count reflects whatever granularity is in the index (timestamps vs. dates), so you should normalize datetimes to calendar or business-day granularity beforehand if you intend to count trading days specifically.

Finally, note some operational trade-offs: index.unique is typically efficient and fine for routine logging, but on extremely large datasets you may want to cache these counts or check index.levels (with care, since levels can include unused categories) to avoid extra work. This print-statement is therefore a lightweight, human-readable assertion that the dataset has the expected coverage before you proceed to feature engineering, backtesting, or model training.

Select the 500 Most-Traded Stocks

dv = data.close.mul(data.volume)This single line computes the per-bar dollar volume for each instrument by multiplying price by traded quantity: element-wise multiplication of the close price series with the corresponding volume series produces a new series (or DataFrame) where each cell is close * volume for that timestamp and asset. In pandas, using .mul instead of the bare * emphasizes element-wise alignment semantics — the indices and column labels are respected and any misaligned labels yield NaNs rather than silently broadcasting the wrong values — and it lets you later pass a fill_value if you need to treat missing entries specially.

We compute dollar volume because it is a simple, high-signal liquidity metric: price × volume approximates the cash flow traded in that bar and is widely used to screen out illiquid instruments, construct universe filters, and form position-sizing rules. Algorithmic strategies use dollar volume to enforce minimum liquidity thresholds, to compute volume-weighted features (e.g., volume-weighted returns), or to normalize signals (so signals are comparable across names with very different trading activity). Because this is a vectorized operation, it remains efficient across large cross-sections and long time series, which matters when you’re running universe-wide computations in a live or backtest pipeline.

A few practical considerations that explain why you’ll see this pattern in production code: make sure the close series is the correct form (adjusted vs unadjusted) for your objective, because corporate actions change the meaning of raw price times volume; watch NaN propagation — any missing price or volume will produce NaN dollar volume and should be handled (e.g., forward-fill, drop, or set fill_value in .mul); and be aware that raw dollar volume is highly skewed, so most downstream logic applies smoothing (rolling mean/median) or a log/winsorization transform before thresholding or ranking. Also consider zeros: zero volume entries may indicate off-market days and can break ratio calculations later, so handle them explicitly if you plan to divide by dollar volume.

In short, dv = data.close.mul(data.volume) is the vectorized creation of a core liquidity feature — dollar volume — which you will typically smooth, normalize, and use as a guardrail or weight in subsequent algorithmic trading decisions (universe selection, risk limits, or weighting schemes).

top500 = (dv.groupby(level=’date’)

.rank(ascending=False)

.unstack(’ticker’)

.dropna(thresh=8*252, axis=1)

.mean()

.nsmallest(500))This one-liner builds a stable universe of 500 tickers by turning a daily signal (dv) into per-date ranks, collapsing that into a ticker-by-time matrix, filtering out thin/incomplete series, and choosing the tickers with the best average rank over time. The input dv is expected to be indexed by date and ticker (a long Series or MultiIndex DataFrame). First we group by date and call rank(…, ascending=False) so that, on each trading day, the largest dv values receive the best (numerically smallest) ranks. Ranking per-date normalizes across different days and removes scale/outlier effects — we care about relative standing on each day, not the absolute magnitude of dv, which can vary over time and across instruments.

.unstack(‘ticker’) turns the per-date ranks into a 2‑D matrix with dates on the rows and tickers on the columns. That layout makes it trivial to measure a ticker’s persistence: we can compute summary statistics across the time axis for each column. Before summarizing, dropna(thresh=8*252, axis=1) removes any ticker column that doesn’t have at least 8*252 non-missing daily observations; this is a business rule to require roughly eight years of data (assuming ~252 trading days per year). The goal is to avoid including recently listed, illiquid, or otherwise sparse series that would make a long-term ranking unreliable.

After filtering, .mean() computes the time-series average of the per-day ranks for each remaining ticker. Averaging ranks (rather than averaging the raw dv) gives a robust, ordinal measure of sustained outperformance: a low mean rank means the ticker was frequently near the top of the daily leaderboard. Finally, .nsmallest(500) selects the 500 tickers with the lowest mean ranks — i.e., the 500 instruments that have been most consistently highly ranked by dv over the required history. Note two practical points: (1) pandas’ rank has tie-breaking behavior and a default method (usually ‘average’) so ties are handled consistently but not explicitly customized here; (2) unstacking creates a wide matrix in memory, so for extremely large universes you may want a streaming or chunked implementation instead of materializing the full DataFrame. Overall, this produces a stable, historically validated top-500 universe suitable for downstream portfolio construction or signal backtests.

Visualize the 200 Most Liquid Stocks

top200 = (data.close

.mul(data.volume)

.unstack(’ticker’)

.dropna(thresh=8*252, axis=1)

.mean()

.div(1e6)

.nlargest(200))

cutoffs = [0, 50, 100, 150, 200]

fig, axes = plt.subplots(ncols=4, figsize=(20, 10), sharex=True)

axes = axes.flatten()

for i, cutoff in enumerate(cutoffs[1:], 1):

top200.iloc[cutoffs[i-1]:cutoffs[i]

].sort_values().plot.barh(logx=True, ax=axes[i-1])

fig.tight_layout()

This block is building a simple liquidity screen and then visualizing the distribution of average daily dollar volume for the most liquid names. The first pipeline computes a per-ticker liquidity metric: it multiplies price by volume to get dollar volume per observation, reshapes the Series into a date × ticker DataFrame with unstack(‘ticker’), then drops tickers that don’t have enough historical data (dropna(thresh=8*252, axis=1)). The threshold 8*252 enforces that only tickers with roughly eight years of trading history are kept, which reduces noise from recently listed or intermittently traded symbols and helps ensure the average reflects a stable trading profile rather than short-lived spikes. After that it takes the time-series mean for each remaining ticker to produce average daily dollar volume, divides by 1e6 to express the values in millions for readability, and selects the top 200 tickers by that metric with nlargest(200).

The second part prepares a compact visualization that breaks the top 200 into four equal buckets of 50 and plots each bucket on its own horizontal bar chart. The cutoffs array [0, 50, 100, 150, 200] defines those 50-name slices; the loop iterates through the successive ranges, uses iloc slicing to grab each 50-element block, sorts values ascending so the horizontal bars progress from small to large within each subplot, and plots them with a log-scaled x axis (logx=True). Using a logarithmic scale is important here because dollar volume is highly skewed — a few very liquid names can be orders of magnitude larger than the rest — and the log scale makes the within-bucket distribution and relative differences readable without the largest names dominating the visualization. sharex=True ensures all subplots use the same x-axis scale so cross-bucket visual comparisons are meaningful.

A few subtle but intentional choices: unstacking into ticker columns allows easy per-ticker aggregation and dropping columns by a non-null count threshold; taking a raw mean gives a simple, interpretable central tendency for liquidity (but be aware it is sensitive to outliers or regime changes — median or a trimmed mean could be alternatives if you worry about episodic spikes); dividing by 1e6 and using barh improves interpretability and label placement for long ticker names; and slicing the top 200 into four ordered buckets rather than plotting all 200 in a single chart produces more legible, comparable panels for inspection.

Operationally, this screen is aligned with algorithmic trading goals: it prioritizes tradability (dollar volume) to limit universe selection to names we can reasonably execute in and it visually surfaces the liquidity profile so you can validate that the selected universe is consistent with your execution assumptions. One caution: the dropna threshold is an absolute count of non-missing days, so you should ensure your date index and missing-data semantics match the intended historical window; also consider whether averaging across the entire history is appropriate if liquidity regimes have materially changed over the lookback.

to_drop = data.index.unique(’ticker’).difference(top500.index)This line builds the list of tickers in the raw dataset that we intend to remove from the trading universe. It first asks the DataFrame index for the unique values of the index level named “ticker” (so we get one label per ticker present in the data), then computes the set difference between that collection and the index of top500. The result, assigned to to_drop, is an Index-like collection of ticker labels that appear in data but do not appear in top500.

Functionally, this is a filtering decision: we identify all symbols that are outside our target universe (the top500) so that subsequent code can remove them from the dataset before feature engineering, signal generation, or backtesting. Doing this up front reduces noise and cost in downstream stages — fewer instruments means less memory, fewer computations, and a focus on highly liquid, investable names that better match execution assumptions for the algorithmic strategy.

A few implementation notes to be aware of: .unique(‘ticker’) assumes the index has a named level “ticker” (MultiIndex) and returns a deduplicated index of labels, and .difference performs label-based set subtraction against whatever object top500.index is (so the dtypes and naming must be compatible). This line itself does not mutate data; it only computes which tickers to drop. If top500 is a plain list/array or uses a different naming/dtype, you should normalize types or use isin-based filtering instead to avoid subtle mismatches.

len(to_drop)

This single expression is an explicit, programmatic checkpoint: it evaluates how many items have been marked for removal (the length of the collection held in to_drop) so the rest of the pipeline can decide what to do next. In an algorithmic trading workflow, to_drop is typically the result of an earlier cleaning or feature-selection step — for example, columns with too many NaNs, instruments filtered out by liquidity or volume rules, features with near-zero importance from a model, or individual time-series rows flagged as outliers. Knowing the count is useful for control flow (skip the drop step if there’s nothing to remove), for logging and telemetry (record how many features or assets you pruned this run), and for risk checks (abort or raise an alert if an unusually large number of items are being removed, which may indicate upstream data corruption).

Why we do this explicitly: the numeric count is easier to reason about and compare against thresholds than the raw collection. Subsequent code will typically branch on whether len(to_drop) == 0, len(to_drop) > some_limit, or use the value in a metric emitted to monitoring so engineers and quants can track data quality over time. Using len() is also more explicit than relying on truthiness (if to_drop:) when you want the concrete number for alerts, conditional thresholds, or structured logs.

A few practical considerations: len() is constant-time and cheap for standard sequence and collection types (list, tuple, pandas Index, numpy array) because they implement __len__, so this check won’t be a performance bottleneck even in loops. Avoid calling len() on a generator or iterator (it will raise TypeError or require exhausting the iterator), and guard against to_drop being None if upstream logic can produce None — otherwise you’ll get a TypeError at runtime. If you need to both count and later iterate a generator, materialize it into a list first (aware of memory cost).

In short, this line is a small but important decision point in the data-preparation flow for the trading system: it quantifies what the cleaning/selection logic produced so downstream processes can act deterministically and so operations and alerts can be driven by concrete, auditable counts.

data = data.drop(to_drop, level=’ticker’)This line removes all observations in the dataset that belong to one or more tickers listed in to_drop, operating on a MultiIndex whose level is named “ticker”. Concretely, pandas locates the index level named “ticker” and deletes every index entry where that level matches any value in to_drop, returning a new DataFrame (or Series) that is then reassigned to data. Because the operation targets the index level, the removal is applied across all other index dimensions (e.g., dates, exchanges), so you end up with no rows for the dropped tickers at any timestamp.

We do this to constrain the trading universe before downstream processing: removing symbols with insufficient history, extreme outliers, delisted equities, or known bad data prevents those instruments from contaminating feature calculations, model training, or backtests. Excluding such tickers early reduces noise in cross-sectional signals, avoids look‑ahead or survivorship biases from partial histories, and keeps aggregation/groupby operations simpler and faster because they no longer need to handle special-case tickers.

A few practical behaviors and pitfalls to be aware of: drop by level returns a copy, not an in‑place mutation, which is why the result is reassigned to data. If any value in to_drop is not present in that index level, pandas will raise a KeyError unless you pass errors=’ignore’. The level name must exactly match an index level name; if “ticker” is instead a column or has a different name, the call will fail or do nothing. Also, because this is an index-level operation, it removes all rows where the ticker matches — if you only intended to remove certain dates or contexts for a ticker, use a boolean mask instead.

As a best practice in the algo‑trading pipeline, ensure to_drop is derived deterministically (for example based on minimum trade days, price thresholds, or liquidity filters), and consider logging the removed tickers and the pre/post row counts. If you expect occasional non-existent tickers, use errors=’ignore’ to make the operation robust in batch runs. This keeps the dataset clean and predictable for feature engineering, model fitting, and rigorous backtesting.

data.info(null_counts=True)

This single call invokes pandas’ DataFrame.info to produce a concise structural summary of the dataset: it lists the index dtype and range, each column name with its dtype, the count of non-null entries per column (because null_counts=True), and an estimate of the DataFrame’s memory usage. Conceptually, the method scans the frame to determine each column’s type and number of present (non-NaN) values and then prints those diagnostics to stdout; it does not mutate the DataFrame or return those numbers for further programmatic use.

In the context of algorithmic trading this is a rapid, defensive check that informs immediate data-quality and performance decisions. The non-null counts surface holes in price, volume, or timestamp series that would otherwise propagate NaNs through indicator calculations, break resampling/grouping, or bias backtest results; seeing many missing values should drive a decision to impute, forward-fill, backfill, drop, or filter affected time ranges before computing signals. The dtypes call attention to columns that may need conversion (e.g., object timestamps that must be parsed to datetime64, numeric columns stored as object, or low-cardinality string columns better stored as category) — converting types both fixes logic errors and materially reduces memory and CPU cost when backtesting on multi-day or high-frequency data.

A few practical caveats and next steps follow from the call: computing non-null counts is an O(N) scan and can be expensive on very large tables, and the older null_counts argument may be replaced by show_counts in newer pandas versions; also, the printed memory estimate can understate usage for object columns unless you request a deep inspection. After reviewing info(), typical follow-ups are to run data.isna().sum() for explicit missing-value counts, data.memory_usage(deep=True) and dtype downcasting for performance, parse and set a datetime index, and assert index monotonicity/uniqueness so downstream resampling and lookback windows behave deterministically. Overall, info() is a quick diagnostic to decide whether to clean, convert, or optimize the dataset before feeding it into signal generation and backtesting pipelines.

print(f”# Tickers: {len(data.index.unique(’ticker’)):,.0f} | # Dates: {len(data.index.unique(’date’)):,.0f}”)

This single line is a compact runtime sanity check that prints how many distinct instruments and trading dates are present in the dataset. Internally it treats data.index as a pandas Index/MultiIndex with named levels ‘ticker’ and ‘date’. The call data.index.unique(‘ticker’) extracts the unique labels for the ticker level, len(…) then counts them, and the same happens for the date level. The f-string prints both counts in a human-readable form using comma thousand-separators and zero decimal places so the numbers look like natural integers in the console.

Why this matters for algorithmic trading: the number of tickers gives you the cross-sectional breadth (how many instruments your strategy can operate on), while the number of dates gives you the temporal depth (how many observations you have to train backtests or estimate statistics). Verifying these two dimensions early helps catch common issues — missing or unexpectedly filtered symbols, accidental date truncation, or upstream joins that duplicated rows or dropped a level — before downstream model training, factor estimation, or portfolio construction.

A few practical notes and caveats. Using Index.unique with a level name assumes your index actually has named levels ‘ticker’ and ‘date’; if the index is not a MultiIndex or the names differ, this will raise an error, so it’s worth validating the index schema earlier in the pipeline. Also, unique(…) returns the distinct labels across the whole dataset, so the date count is global (not per ticker); if you need per-instrument series lengths or to detect uneven coverage, you’d compute per-ticker counts separately. Finally, the approach is fine for interactive checks and moderate-sized datasets; for very large indexes repeatedly materializing unique arrays can be more expensive than using nunique() or aggregated group counts when performance matters.

Remove Outlier Observations Based on Daily Returns

before = len(data)

data[’ret’] = data.groupby(’ticker’).close.pct_change()

data = data[data.ret.between(-1, 1)].drop(’ret’, axis=1)

print(f’Dropped {before-len(data):,.0f}’)

This snippet first captures the original row count so we can quantify how much data the cleaning step removes. That baseline is important in algorithmic trading pipelines because you want visibility into how many ticks or candles are being thrown away at each stage — large, unexplained drops can indicate upstream data issues.

Next, it computes per-ticker percentage returns by taking the percent change of the close price within each ticker group. Grouping by ticker ensures the return calculation uses the previous close for the same instrument and does not accidentally compute returns across different symbols, which would produce meaningless large deltas. The percent-change operation will introduce NaN for the first row of every ticker (no prior price) and will produce very large magnitude numbers when there are price discontinuities (e.g., bad ticks, splits, or data errors).

The code then filters rows to keep only returns in the inclusive range [-1, 1] and immediately drops the temporary ‘ret’ column. Constraining returns to this window effectively excludes impossible or suspicious moves (beyond ±100%) that could destabilize downstream models or trigger false trading signals — for example, a 10,000% return from a misreported price would otherwise dominate feature distributions, backtests, or risk calculations. Because NaN is not “between” any two numbers, the initial NaNs from pct_change are also removed by this filter, which is a convenient way to drop the first row per ticker. Dropping the ‘ret’ column afterward keeps the DataFrame schema clean for subsequent processing.

Finally, the print statement reports how many rows were removed, formatted with thousand separators for readability. This lightweight logging provides quick feedback during data preparation so you can detect abnormal loss rates and investigate issues like missing split adjustments or bad ticks if too many rows are dropped.

tickers = data.index.unique(’ticker’)

print(f”# Tickers: {len(tickers):,.0f} | # Dates: {len(data.index.unique(’date’)):,.0f}”)

This snippet is operating on a pandas object whose index is a MultiIndex with levels named ‘ticker’ and ‘date’. The first line pulls the set of unique ticker identifiers from the index level ‘ticker’ — not by scanning the DataFrame rows but by asking the index for its unique labels at that level. Conceptually this yields the trading universe represented in the dataset (each distinct symbol that appears anywhere in the time series).

The second line prints a compact, human-readable summary: it counts the number of unique tickers and the number of unique dates across the entire index and formats those counts with thousands separators and no decimal places. Using index.unique(‘date’) gives the total distinct trading days present in the dataset (across all tickers), and the f-string formatting :,.0f makes the output easier to scan when working with large datasets.

In an algorithmic trading context this is a quick, inexpensive sanity check performed at the start of a backtest or data pipeline run. The ticker count tells you the available universe for selection, portfolio construction, and any universe-level constraints; the date count tells you the historical depth and whether you have enough lookback to compute features or rolling statistics. Because unique collapses duplicates, this check also helps reveal data quality issues implicitly — for example, if different tickers have different date coverage you’ll still get the aggregate date count here, so the next step is usually per-ticker completeness checks (or looking for unexpected duplicates or missing trading days). Also be aware this approach assumes the index actually contains levels named ‘ticker’ and ‘date’ — if those levels are missing or named differently, the call will fail and you should map to the correct index levels before running downstream logic.

Sample price data (for illustration)

ticker = ‘AAPL’

# alternative

# ticker = np.random.choice(tickers)

price_sample = data.loc[idx[ticker, :], :].reset_index(’ticker’, drop=True)The first line picks which universe member we want to extract: here it’s fixed to ‘AAPL’, but the commented alternative shows this spot is sometimes used to draw a random ticker from the available tickers when building training batches or running stochastic backtests. Choosing a single ticker at this stage is deliberate — downstream signal generation and strategy logic typically operate on a contiguous time series for one instrument, so we either target a specific asset for analysis or sample one at random to encourage model generalization across symbols.

The second line performs the actual extraction from a DataFrame whose index is a MultiIndex with a ticker level and a time (or other) level. Using idx[…] (the common alias for pandas.IndexSlice) allows clean, readable slicing when one index level is being fixed (ticker) and the other level is a full slice (:). That .loc call selects all rows that belong to the chosen ticker while keeping all columns. This is both semantically clear and efficient: it avoids manually masking or filtering the whole DataFrame and returns only the contiguous block of rows for that instrument, which is what time-series computations require.

Finally, .reset_index(‘ticker’, drop=True) removes the ticker level from the index while leaving the remaining level(s) — typically a DatetimeIndex — as the primary index for the resulting object. We drop rather than keep the ticker because it would be constant for this slice and would only clutter downstream code; most feature engineering, return calculations, and model inputs expect a single-level time index. Removing the ticker also avoids accidental grouping or joins keyed on a constant value. If you do need to preserve the symbol for bookkeeping, store it separately before resetting. Note also that this code will raise a KeyError if the ticker is not present; when sampling randomly in training, ensure reproducibility by seeding the random generator or validate membership beforehand.

price_sample.info()

Calling price_sample.info() is a lightweight diagnostic step that prints a compact summary of the DataFrame’s structure so you can quickly validate what you just ingested. In the typical data pipeline it sits immediately after loading or receiving a price feed: we want to know which columns arrived, which columns are numeric versus object/strings, how many non-null values each column has, and an estimate of the memory footprint. That single snapshot drives several downstream decisions without mutating the data — it helps you decide whether to convert types, impute or drop missing rows, or downcast to save memory before heavy computation.

From an algorithmic-trading perspective the reasons are practical and safety-oriented. Many failures in backtests and live strategies come from wrong dtypes (e.g., prices stored as object/strings, timestamps not converted to datetime) or hidden NaNs that will propagate through indicator calculations and fill or cause misalignment during joins. The info() output flags exactly those problems: if price columns are non-numeric you know to coerce them to float; if the index or timestamp column is missing or has many nulls you know to reconstruct or reindex; if memory usage is large you’ll consider downcasting or streaming processing to avoid OOM during feature computation.

Operationally, use the info() result to decide a small set of corrective steps: convert timestamp columns to a proper DatetimeIndex (so resampling and rolling windows behave deterministically), force numeric price columns to floats and handle non-numeric tokens, address NaNs via forward/back fill or removal according to your fill strategy, and optimize dtypes (int8/float32) if memory is a concern for large tick datasets. Also be aware info() is a read-only, console-oriented probe — for deeper memory analysis use memory_usage=’deep’ or follow with head()/describe() to inspect values that led to the types you observed.

In short, price_sample.info() is an early-validation tool that tells you whether the raw price snapshot is structurally ready for feature engineering, indicator computation, or backtesting, and it steers immediate preprocessing choices to prevent subtle, costly errors later in the trading pipeline.

price_sample.to_hdf(’data.h5’, ‘data/sample’)This single line persists an in-memory price timeseries (price_sample) into an on-disk HDF5 store so the same cleaned/processed data can be reloaded later without re-running upstream ETL or feature construction. Concretely, pandas serializes the DataFrame/Series into the HDF5 container at path/key “data/sample” inside the file data.h5; the key creates a group-like hierarchy (so you can store multiple named tables/objects under the same file). The operation writes the index and column dtypes so your timestamp index and numeric price columns are preserved, which is important for deterministic backtests and reproducing signals.

We do this because HDF5 (via PyTables) is optimized for large numeric arrays: it gives fast binary I/O, efficient random access, and good compression/chunking options, so saving large historical price matrices is both space- and time-efficient compared with text formats. That efficiency matters in algorithmic trading workflows where backtests need many iterations on the same historical window and where loading speed can become a bottleneck.

A few practical implications to keep in mind for production-quality use: pandas.to_hdf defaults to a “fixed” (non-appendable) format unless you pass format=’table’, so if you plan to append new samples or run queries/filtering directly inside the HDF store, choose format=’table’ and appropriate compression/complevel. Also ensure PyTables is available; consider using a context-managed HDFStore when doing multi-step writes to avoid corruption on interruption, and be aware that HDF5 files are not a transactional or multi-writer store — concurrent writes or distributed use-cases often call for different storage (e.g., Parquet, a database, or a time-series DB). Finally, include meaningful filenames or keys (timestamps, version tags) and document the schema so downstream backtests and live systems load the exact dataset intended.

Group Data by Ticker

Organize records so that entries with the same ticker symbol are grouped together.

by_ticker = data.groupby(level=’ticker’)This line takes your time-series table (presumably a pandas DataFrame or Series whose index includes a level named “ticker”) and creates a GroupBy object that partitions the rows by instrument. Conceptually, you are telling pandas: “treat each instrument as an independent dataset.” That grouping is the foundation for every per-instrument computation that follows — per-ticker returns, moving averages, volatility estimates, z-score normalization, signal generation, per-instrument resampling, etc. — and it enforces the most important correctness constraint in algorithmic trading: no information should leak across tickers when computing metrics or signals.

Mechanically, groupby(level=’ticker’) is lazy: it doesn’t perform heavy computation immediately, it just records the grouping metadata and how to slice the original data. When you call aggregation or transformation methods (agg, transform, apply, rolling, resample, etc.), pandas will iterate over each ticker group and apply the requested operation to that group’s rows. Choose the operation type intentionally: use transform when you need a same-length, aligned result back on the original index (e.g., per-row z-score or demeaned returns), use agg when you want reduced summaries (e.g., daily realized volatility per ticker), and prefer built-in vectorized groupby methods or groupby.rolling for efficiency rather than groupby.apply which can be much slower.

A few practical and correctness-focused details to keep in mind. groupby(level=’ticker’) groups by the index level, so if your tickers are columns rather than an index layer you must group by the column name instead. By default pandas sorts group keys which can reorder groups; if preserving original row order is important for subsequent logic, pass sort=False. Some operations (e.g., groupby().rolling or groupby().resample) produce a MultiIndex in the result (ticker plus the original time index), so be explicit about index handling to avoid misalignment. Also note the memory/performance tradeoffs: the GroupBy object is inexpensive, but repeated expensive apply calls over many small groups can be a bottleneck — prefer transform/agg or consider parallelization frameworks (dask/joblib) if you must scale across many tickers.

In short, this single line is the switch that turns a flat multi-instrument dataset into a set of independent per-instrument pipelines. It’s how you guarantee per-ticker isolation for feature engineering and signal generation, and how you enable efficient, vectorized computations that are essential for correct and scalable algorithmic trading.

Historical Returns

T = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10, 21, 42, 63, 126, 252]This single line defines the set of time horizons (T) that your trading logic will use as lookback windows for feature calculation and signal generation. In an algorithmic trading pipeline the raw price/time series flows through a stage that computes time-scale-specific statistics — returns, moving averages, volatility, momentum indicators, z‑scores, etc. — and T enumerates the different window lengths over which those statistics are computed. Practically, for each timestamp t you will compute features like the T-day return, rolling standard deviation, or an EWMA (using T as an effective span) using only data up to t−1 so you preserve causality.

The particular values are purposeful: 1–5 capture ultra-short horizons (tick-to-daily microstructure, very short-term mean reversion or immediate momentum), 10 and 21 capture short-intermediate horizons (two-week and roughly one-month behavior), and 42, 63, 126, 252 progressively capture multi-month to full-year effects (2 months, ~3 months/quarter, ~6 months, and a trading-year). Structuring horizons this way gives a multi-scale view of market behavior: short windows respond quickly to recent shocks, medium windows capture cyclical or regime tendencies, and long windows pick up structural trends or slowly evolving volatility. The roughly doubling spacing in the longer windows reduces redundancy while covering an order-of-magnitude range of timescales, which is important because many market phenomena are scale-dependent.

Why this matters algorithmically: combining features from multiple T values helps models distinguish transient noise from persistent signals and lets portfolio rules choose the horizon that best balances signal-to-noise and transaction cost tradeoffs. However, overlapping windows create highly correlated features (e.g., the 21-day and 42-day returns share much information), so you should expect multicollinearity — handle it with feature selection, regularization, dimensionality reduction, or by building meta-features (differences, ratios, or normalized scores) rather than feeding all raw windows blindly into a model.

Operational considerations follow directly from the choice of T. Compute rolling statistics in a vectorized, streaming-safe way (pandas/numba/cy libraries or online algorithms) and cache results to avoid repeated work across multiple signals. Ensure all computations are aligned to trading-day counts (these numbers assume trading days) and maintain strict look-ahead protection. Also normalize or annualize features appropriately before model training (e.g., scale returns by sqrt(T) or use z-scores) so that the model does not implicitly overweight longer-horizon features just because they have larger raw magnitudes. Finally, treat this list as a hyperparameter: you can tune, prune, or replace it with an exponentially weighted family or a coarser logarithmic grid to reduce dimensionality while preserving multi-scale coverage.

for t in T:

data[f’ret_{t:02}’] = by_ticker.close.pct_change(t)This loop iterates over a set of lookback periods T and, for each period t, computes the t-period simple return for each ticker and stores it as a new column on the main data table. Concretely, by_ticker is a grouped view keyed by ticker (so operations respect group boundaries), and by_ticker.close.pct_change(t) computes (close_now − close_t_bars_ago) / close_t_bars_ago for every row within each ticker group; assigning that Series into data[f’ret_{t:02}’] attaches the result to the same index so the row-level alignment is preserved. The zero-padded column name (‘ret_01’, ‘ret_05’, etc.) is deliberate: it keeps columns lexically ordered by horizon and makes downstream selection and display predictable.

We do this because multi-horizon simple returns are common, lightweight features for algorithmic trading models: short- and medium-term returns encode momentum, mean-reversion signals, and provide candidate target variables or risk-adjusted inputs. Computing returns per-group ensures we don’t leak information across different tickers and that the percent-change is measured over t observed bars (not calendar days), which is the expected behavior when T is specified in bar counts. Using pct_change keeps the computation vectorized and efficient compared with looping rows or manual shifts.

There are important practical choices and caveats tied to this implementation. pct_change produces NaN for the first t rows of each ticker and whenever close is missing, so you must decide how to treat those rows (drop, impute, or mask in training). pct_change yields arithmetic returns, not log returns; arithmetic returns are intuitive and directly interpretable for many strategies, but if you need additivity over time or better numerical properties for aggregation, consider using log-return (diff of log price) instead. Also ensure close is adjusted for corporate actions (splits/dividends) if you want economically correct returns; otherwise large discontinuities may create misleading signals. Finally, if T is large or contains many values, the repeated group operations are still vectorized but can be optimized further (e.g., compute log-price once and take shifted differences for many horizons) and you should guard against extreme outliers (clip or winsorize) if they would otherwise destabilize models or risk metrics.

Forward Returns

data[’ret_fwd’] = by_ticker.ret_01.shift(-1)

data = data.dropna(subset=[’ret_fwd’])The two lines create the supervised learning target — the “next-period” return — and then remove any rows that no longer have a valid target. Concretely, by_ticker.ret_01.shift(-1) takes the current series of single-period returns (ret_01) and moves every value up by one row so that the return that actually occurs at time t+1 is placed on the row for time t; assigning that shifted series to data[‘ret_fwd’] turns it into the label we want the model to predict. Using shift(-1) (a negative shift) is important because it produces a forward-looking label (the immediate next return) rather than a lagged feature. Index alignment matters here: the shifted Series must be aligned with data’s index and — critically — the shift must have been done within each ticker’s chronological ordering so you don’t accidentally assign one ticker’s next return to a different ticker (that would introduce label leakage).

The dropna call then removes any rows where ret_fwd is NaN. Those NaNs occur wherever there is no “next” return available — typically the last timestamp for each instrument — and we must remove them because they are unlabeled and therefore unusable for supervised training or backtesting. Note that dropna(subset=[‘ret_fwd’]) only drops rows missing the target and leaves rows with other missing feature values intact; this keeps the dataset consistent while ensuring every retained row has a valid forward return. Operationally, before doing this you should ensure your data is sorted by ticker and time and that the shift was applied per-group; otherwise you risk misaligned labels or look‑ahead leakage, which would bias model evaluation and trading decisions.

Persist Results

Return only the rewritten text.

data.info(null_counts=True)

When you call data.info(null_counts=True) Pandas examines the DataFrame and emits a concise, human-readable summary that helps you quickly assess completeness and shape of the dataset before any modeling or backtest. Concretely, the method walks every column, determines its dtype, counts how many non‑null entries are present (the null_counts=True flag requests these counts), and reports the overall index range and approximate memory footprint. The key purpose here is diagnostic: for algorithmic trading you need to know which fields contain missing values, which columns are stored with inefficient or unexpected dtypes, and how large the in‑memory representation is so you can make safe, performant preprocessing and backtest decisions.

Why that matters in practice: many trading algorithms depend on continuous, correctly-typed time series (prices, volumes, timestamps, and engineered features). Non‑null counts immediately reveal columns with missingness patterns that could break rolling/windowed indicators, cause NaN propagation through feature pipelines, or invalidate model training and evaluation. Seeing an unexpectedly low non‑null count on a price or target column tells you to investigate data ingestion, alignment, or market-hours gaps; seeing an object dtype where you expected numeric suggests parsing problems (commas, symbols, or mixed types) and that downstream vectorized math will be slow or incorrect. The memory usage summary helps you decide whether to downcast floats/ints or convert high‑cardinality strings to category to reduce RAM — a practical concern when holding long tick-level histories for many instruments.

How you typically act on the output: columns with near‑complete absence of data can be dropped; partially missing numeric features can be imputed with forward/backfill, interpolation, or model‑based imputers depending on causality and market microstructure; time columns should be coerced to datetime and set as the index to support resampling and alignment; object columns that are actually numeric should be coerced and cleaned to avoid surprises; and large memory footprints should prompt dtype downcasting or chunked processing. Note also that info prints to stdout for quick inspection; for programmatic checks you’d complement it with data.isna().sum(), data.memory_usage(deep=True), or dtype-specific analyses. Finally, be aware that some recent Pandas versions flag null_counts as deprecated — the summary will still appear but you may prefer the default info() behavior or explicit alternatives to avoid warnings.

data.to_hdf(’data.h5’, ‘data/top500’)This single call is serializing a pandas time-series or tabular object into an HDF5 container so it can be efficiently persisted and reloaded later in the trading pipeline. Concretely, the DataFrame referred to as data is being written into the file data.h5 under the internal HDF5 group/key “data/top500”. In HDF5 terms that key functions like a path inside the file: it gives you a namespaced location where the dataset will live, which makes it easy to store multiple logical tables (for example, different universes, snapshots, or preprocessing stages) in the same physical file.

Why use HDF5 here? For algorithmic trading we often work with large, columnar time series that need fast sequential reads and reasonably fast random access for slices; HDF5/PyTables gives both. Storing the cleaned, normalized or aggregated “top500” dataset to HDF5 minimizes round-trip parsing cost (CSV/JSON are expensive), preserves index and dtypes so downstream backtests and feature pipelines see deterministic inputs, and supports on-disk compression to reduce footprint. It also lets you version or namespace datasets in one file instead of scattering many files on disk.

There are important behavioral choices implicit in this call that affect performance and future operations. pandas.to_hdf uses PyTables under the hood and supports two main formats: “fixed” (fast to write/read but not appendable or queryable) and “table” (slower, but allows appends and where queries). The default usage here will produce a fixed-format dataset unless you explicitly pass format=’table’ or append=True; that choice matters if you plan to incrementally add ticks or daily snapshots. If you need to query on columns or append new rows frequently, prefer format=’table’ with data_columns set for the fields you will filter on. If you only create snapshots and read them back wholesale (typical for backtests), fixed format is faster.

Also be mindful of concurrency and deployment constraints: HDF5 files are not a robust multi-writer database. They work well for single-writer, many-reader patterns — so write in batches from a single upstream process (for example, end-of-day or periodic snapshots) and let multiple consumers read. Avoid using HDF5 as a high-frequency, multi-process feed store; for that use a true time-series database or message bus. Additionally, consider compression (complevel/complib) to save disk at the cost of CPU on write/read, and be cautious about atomicity and network filesystems — writes may not be atomic across NFS and similar.

Operationally, if you need more control, use a pd.HDFStore context so you can set mode, format, compression, and then close the store explicitly; and always test read-back with pd.read_hdf(‘data.h5’, ‘data/top500’) to verify indexes and types are preserved. Finally, think about naming/versioning the key (for example include a date or run-id) if you need reproducible backtests or to retain historical snapshots rather than overwriting the same key. These practices keep HDF5 a fast, reliable way to persist intermediate and historical datasets in an algorithmic trading stack.

Common Alpha Factors

An overview of commonly used alpha factors.

%matplotlib inline

from pathlib import Path

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import pandas_datareader.data as web

import statsmodels.api as sm

from statsmodels.regression.rolling import RollingOLS

from sklearn.preprocessing import scale

import talib

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as snsThis block sets up the toolkit we’ll use to build, analyze and visualize algorithmic trading signals. At a high level the workflow you should picture is: retrieve time series market data, construct features and technical indicators, estimate time-varying relationships or models on moving windows, standardize and convert outputs into trading signals, and finally inspect and validate the signals with visual diagnostics. The imports here give us the primitives for each of those stages.

Pathlib provides a robust way to manage filesystem paths when we cache or read saved market data and model artifacts; prefer Path objects over string paths so the code behaves consistently across environments and OSes. Numpy and Pandas are the core numerical and time-series containers: use Pandas DataFrames indexed by timestamp to align multiple instruments, resample or reindex for matching bar frequencies, and use NumPy where you need efficient array operations during feature computation or vectorized backtests.

pandas_datareader (web) is the common convenience for pulling historical market prices from web APIs; the expectation is that you’ll fetch OHLCV series, then use Pandas to align symbols, drop or impute missing timestamps, and construct synchronous matrices of returns or log-prices before modeling. A crucial operational detail: always align and validate timestamps before feeding series into models or TA functions to avoid look‑ahead and misaligned signals.

For statistical modeling we bring in statsmodels.api and RollingOLS. RollingOLS lets us estimate OLS coefficients over a moving window, which is a common pattern in pairs trading and statistical arbitrage: we use rolling regression to estimate a time-varying hedge ratio (beta) between two assets, then compute the spread (residual) as the target for mean‑reversion signals. The key “why” here is that relationships among assets drift over time, so a static single-sample regression will often produce stale hedge ratios; a rolling fit captures recent dynamics. Be mindful of alignment: RollingOLS typically aligns its parameter output to the right edge of the window, so you must ensure you only use parameters available at time t to form a signal at t (no peeking). Also handle the window length and min_periods carefully to balance stability vs. responsiveness.

We import sklearn.preprocessing.scale to normalize variables. Normalization is used in two places: (1) to stabilize numerical conditioning before regression (particularly when mixing price scales or using technical indicators with different units), and (2) to compute z‑scores of residuals or spread for signal thresholds. Practically, normalization must be done without introducing look‑ahead — for rolling z‑scores you should compute mean/std on the in‑sample window, not across the full series.

TA‑Lib provides a large library of standard technical indicators (SMA, RSI, MACD, volatility measures) that you can combine with statistical signals to build filters or confirm entries/exits. TA functions operate on NumPy arrays and typically produce NaNs for the initial lookback period, so you’ll need to merge their outputs back into the DataFrame and manage those NaNs before generating signals or backtests.

Finally, matplotlib and seaborn are for visual diagnostics and exploratory analysis: plot price series, rolling betas, spreads, z‑scores, and cumulative P&L to validate assumptions and detect regime shifts or data issues. In Jupyter, %matplotlib inline ensures figures render inline within the notebook session. Use visual checks (residual histograms, QQ plots, autocorrelation plots, and heatmaps of parameter drift) to catch nonstationarity, structural breaks, or model misspecification before risking capital.

A couple of practical cautions that flow from these choices: always handle missing data (forward/backfill with care), compute rolling statistics and scaling within the same window used for model estimation to avoid leakage, and be explicit about the alignment of model outputs to timestamps when converting parameters and residuals into trade signals. Together, these libraries form a compact, reproducible pipeline for building and validating algorithmic trading strategies that combine statistical regression and classical technical indicators.

sns.set_style(’whitegrid’)

idx = pd.IndexSlice

deciles = np.arange(.1, 1, .1).round(1)The first line sets the global plotting style to Seaborn’s “whitegrid”, which is a deliberate choice for financial charts because it produces a clean, white background with subtle gridlines. In an algorithmic trading workflow you’ll be generating many diagnostic plots — cumulative returns, drawdowns, turnover, factor exposures — so using a consistent, high‑contrast style with gridlines improves readability of value ticks and comparisons across panels and reports. This call affects Matplotlib’s rc settings for the session, so subsequent plots inherit a consistent visual language without changing any data or analysis logic.

The second line creates a convenient alias to Pandas’ IndexSlice helper. IndexSlice itself doesn’t transform data; it’s used with .loc to express complex slices over MultiIndex objects in a compact, readable way (for example selecting all dates for a given symbol or selecting specific decile groups across all time points). In trading code you commonly work with MultiIndex DataFrames (date × symbol, or date × decile), and IndexSlice makes those cross-sectional/time-based selections less error-prone and easier to read than nested tuples of slice objects. In short, it’s a syntactic aid that makes subsequent data extraction and aggregation steps — like building matrices of decile returns or isolating windows for turnover calculations — much clearer.

The third line builds a numeric array of decile cut points: 0.1 through 0.9. These values are the canonical quantile thresholds used to bucket instruments by a factor score (bottom decile, second decile, …, top decile) for aggregation and backtest construction. The explicit rounding to one decimal place is purposeful: floating‑point generation with np.arange can produce artifacts like 0.30000000000000004, which can break equality checks, produce ugly axis labels, or create surprise keys when used as labels/indexers — rounding yields clean, predictable boundaries for grouping, labeling, and plotting. Note that np.arange(.1, 1, .1) intentionally stops before 1.0; for decile bucketing you typically only need these internal cut points (0.1–0.9) to define ten groups. Together, these three lines set up consistent plotting, reliable MultiIndex slicing, and clean decile boundaries — foundational plumbing that keeps downstream factor ranking, grouping, and visualization robust and easy to interpret.

Loading data

data = pd.read_hdf(’data.h5’, ‘data/top500’)

price_sample = pd.read_hdf(’data.h5’, ‘data/sample’)These two lines are doing the initial data ingestion step for a trading workflow: they open an HDF5-backed store and load two named tables into memory as pandas objects. The first read pulls the primary universe or feature table (key ‘data/top500’) into the variable data; in our context that is likely the historical record for the top 500 tickers — prices, volumes, or precomputed features across timestamps. The second read pulls a smaller or targeted table (key ‘data/sample’) into price_sample, which we typically use either as a lightweight price series for quick sanity checks, a look-up table of reference prices for backtests, or a down-sampled snapshot for prototyping signals. Conceptually, the code’s flow is: persistently stored HDF5 -> keyed dataset -> in-memory DataFrame, making both datasets immediately available for downstream alignment, feature engineering, or backtesting logic.