How Five Neural Network Models Reveal Market Insights and Challenge Efficiency

Cracking the Code: Predicting Stock Prices with AI

Link to download source code at the end of this article.

Article 73

Predicting stock prices is tough because the markets can change suddenly. Still, many people and researchers try to forecast them to make money or understand the market better. In our work, we compared five neural network models for predictions: back propagation (BP), radial basis function (RBF), general regression (GRNN), support vector machine regression (SVMR), and least squares support vector machine regression (LS-SVMR). We tested these models on three stocks: Bank of China, Vanke A, and Kweichou Moutai. Our results showed that the BP neural network had the best performance among all five models.

Introduction

Predicting stock prices matters to investors and researchers alike. Investors analyze data to make smart investment choices, while researchers look into stock prediction to test market efficiency and improve methods. However, predicting prices is tough due to the stock market’s constant changes and the impact of factors like politics, company policies, and investor sentiment.

In this article, we examine five AI models for stock price prediction: back-propagation neural networks (BPNN), radial basis neural networks (RBFNN), general regression neural network (GRNN), support vector machine regression (SVMR), and least squares support vector machine regression (LS-SVMR).

BPNN is popular across various fields, including stock forecasting, with some studies enhancing it using wavelet transforms. RBFNN is simpler, effectively recognizing patterns and correcting errors from other models. GRNN shows promise in predicting stock prices, but hasn’t been extensively compared with others. SVM and LS-SVMR are known for strong prediction performance by minimizing risks.

Despite their potential, there’s a lack of direct comparisons among these five methods. We aim to address this by comparing the effectiveness of BPNN, RBFNN, GRNN, SVM, and LS-SVMR in predicting stock prices for three companies: Bank of China, Vanke A, and Kweichou Moutai. The article includes a description of the five models, the data used, our findings, and concludes with our insights.

Let’s break down five types of neural network models.

First up, we have backpropagation (BP) neural networks. They consist of an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer. Each layer’s neurons activate based on the previous layer’s info, and we use weights and biases to represent connections. We keep track of how well the model performs with a cost function and adjust weights and biases based on errors.

Next, there are radial basis function (RBF) networks. These have three layers: input, hidden (with a non-linear function), and a linear output layer. The output depends on input parameters.

Then, we look at generalized regression neural networks (GRNN), a type of RBF network introduced by D.F. Specht in 1991. GRNN has a hidden layer matching the number of training samples, so each neuron’s center is a training sample. It simplifies calculations, removing the need for traditional training.

We also mention support vector regression (SVR), which creates a linear function to predict outcomes. It aims to minimize error to find the best fit line, but struggles with non-linear relationships. To address this, we can use various functions to transform input data for more flexibility.

Finally, there are least squares support vector machines (LS-SVM), which use modified rules for easier computation. We rearrange equations to predict outcomes from new inputs and use different kernel functions in SVR, such as linear and polynomial ones, with the RBF kernel being the most common.

In this section, we outline the data we used, the results we obtained, and how we analyzed those results. We also highlight the reliability of the BP algorithm and suggest that the market isn’t efficient.

We analyzed the adjusted closing prices of three stocks: Bank of China, Vanke A, and Kweichou Moutai, gathering data from January 3, 2006, to March 11, 2018, totaling 427 weekly price points per stock. The stock prices varied: Bank of China ranged from 2–5 RMB, Vanke A from 5–40 RMB, and Kweichou Moutai from 80–800 RMB, making it the priciest stock on the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges.

Our analysis used a straightforward model that predicts next week’s price based on the previous three weeks’ prices. We structured the model with an input layer of three components and an output layer for predictions. We determined the hidden layer’s neurons using a specific formula and set the learning rate through testing.

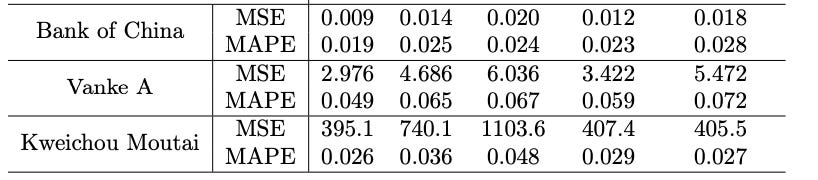

The results showed that all five models we tested could predict stock prices, with the BP model performing best. Even the least effective model had a decent error rate, which is noteworthy for stock predictions. BP outperformed others like SVMR by at least 20% in accuracy for Bank of China and Vanke A.

We also compared models like RBF and LS-SVMR, which had similar accuracy, while GRNN lagged behind. The kernel function used influenced the outcomes; interestingly, a basic linear kernel worked better for SVMR than the more complex RBF kernel.

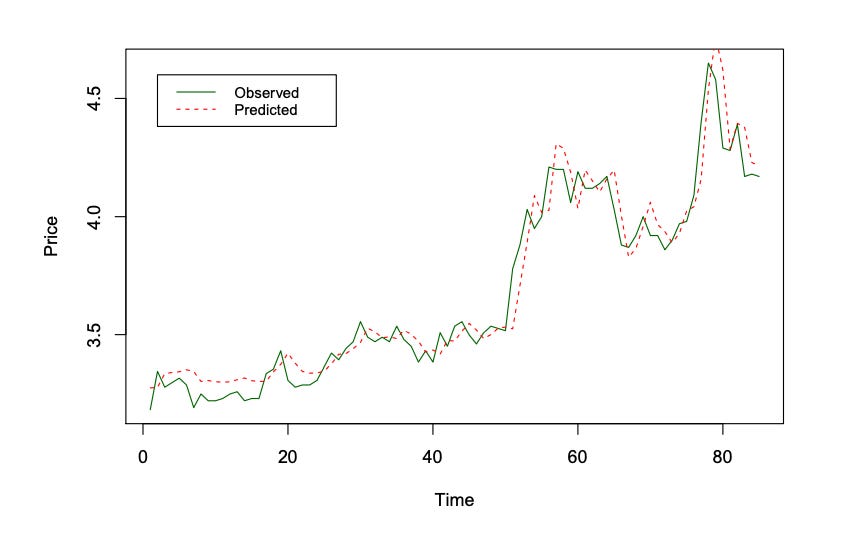

Lastly, we assessed the BP algorithm’s reliability by running it 100 times and found minimal variation in results, confirming its trustworthiness. The predictions closely tracked actual prices for Bank of China, but they seemed to lag by a week, indicating a delay. When we analyzed market efficiency by looking at the differences between predicted and actual prices, we found a bias suggesting that our predictions often underestimated the actual prices. This points to market inefficiency, as prices weren’t as predictable as they should be.

In this article, we found that all five neural network models effectively extracted insights from past prices. The BP model stood out, consistently outperforming the others in forecasting three different stocks. We also tested its stability by running multiple checks. We suggest that readers experiment with settings rather than just sticking to the defaults. We examined errors, questioning the notion of always efficient markets, and plan to explore more complex neural networks in the future.