Quant Toolkit: Signal Engineering, Bounding, and Systematic Asset Allocation — EP-1/365

A Quantitative Study on Bond Flow Anomalies and Volatility-Normalized Portfolio Construction.

Use the button at the end to download source code, all of jupyter notebook and python files.

This article explores the implementation of a multi-factor algorithmic framework designed to capture persistent market inefficiencies across fixed income, equities, and digital assets. We begin by isolating microstructure-driven anomalies, specifically the “Window Dressing” effect in the bond market, utilizing Day of Trading Month (DOTM) temporal filters to exploit non-economic institutional flows. Transitioning from behavioral finance to systematic portfolio construction, we provide a rigorous comparative analysis of risk-premia harvesting techniques, evaluating the impact of monthly rebalancing and dollar-cost averaging on long-term Sharpe ratios and Max Drawdown profiles.

The latter half of the study shifts focus to signal engineering and normalization. We detail the transition from raw time-series momentum to volatility-normalized signals, demonstrating the use of non-linear “squashing” functions — specifically hyperbolic tangent ($tanh$) transformations — to mitigate tail risk and prevent outlier-driven leverage spikes. By the conclusion of this technical guide, readers will have a blueprint for building a robust backtesting pipeline that integrates calendar-based seasonality, cross-asset diversification, and bounded signal logic for algorithmic execution.

Window dressing refers to portfolio managers reshaping their holdings near reporting dates (typically month-end, quarter-end, or year-end) to make portfolios appear safer, cleaner, or more conservative than they actually are.

Elevator pitch

What causes the inefficiency?

The inefficiency arises when large institutional investors make non-economic trades near reporting dates to improve the appearance of their reported holdings. Bond managers often rotate into safer, more liquid securities — for example, short-duration Treasuries — while selling higher-yielding or longer-duration positions to reduce perceived risk on paper. Because these shifts are driven by incentives, compliance rules, and reporting optics rather than fundamentals, they temporarily distort yields, credit spreads, and liquidity, producing a predictable but short-lived mispricing.

Why isn’t it fully arbitraged away?

Even well-informed market participants cannot fully eliminate the effect because the flows are large, price-insensitive, and occur at times when arbitrage capital is constrained. Period-end balance-sheet limits, tighter repo conditions, and regulatory ratios reduce the ability of hedge funds or dealers to take the opposing side. The inefficiencies are small, fleeting, and operationally costly to trade, so professional arbitrageurs only partially offset them. Consequently, forced period-end behavior by large institutions outweighs corrective pressure from arbitrage, allowing the effect to persist.

How might a retail investor harness it?

A retail investor can potentially benefit by timing bond allocations around quarter-end to capture predictable post-window-dressing reversals. High-yield and BBB-rated bonds are often sold into quarter-end and then recover as institutional flows normalize, offering better entry points just after reporting dates. Conversely, short-duration government bonds tend to be overbought before quarter-end and become slightly cheaper afterward. This approach aligns purchases with flow-driven mean reversion rather than attempting to arbitrage transient spreads.

Analysis

The analysis will proceed as follows, using the TLT ticker with visualizations to illustrate the window-dressing effect:

Load OHLCV returns.

Add DOM (day of month) and DOTM (day of trading month) columns.

Compute average returns by DOM and DOTM and plot bar charts/histograms.

Split observations into First 5 Days / Middle Days / Last 5 Days and compare group statistics.

Calculate cumulative mean log-returns by DOM and DOTM and plot them.

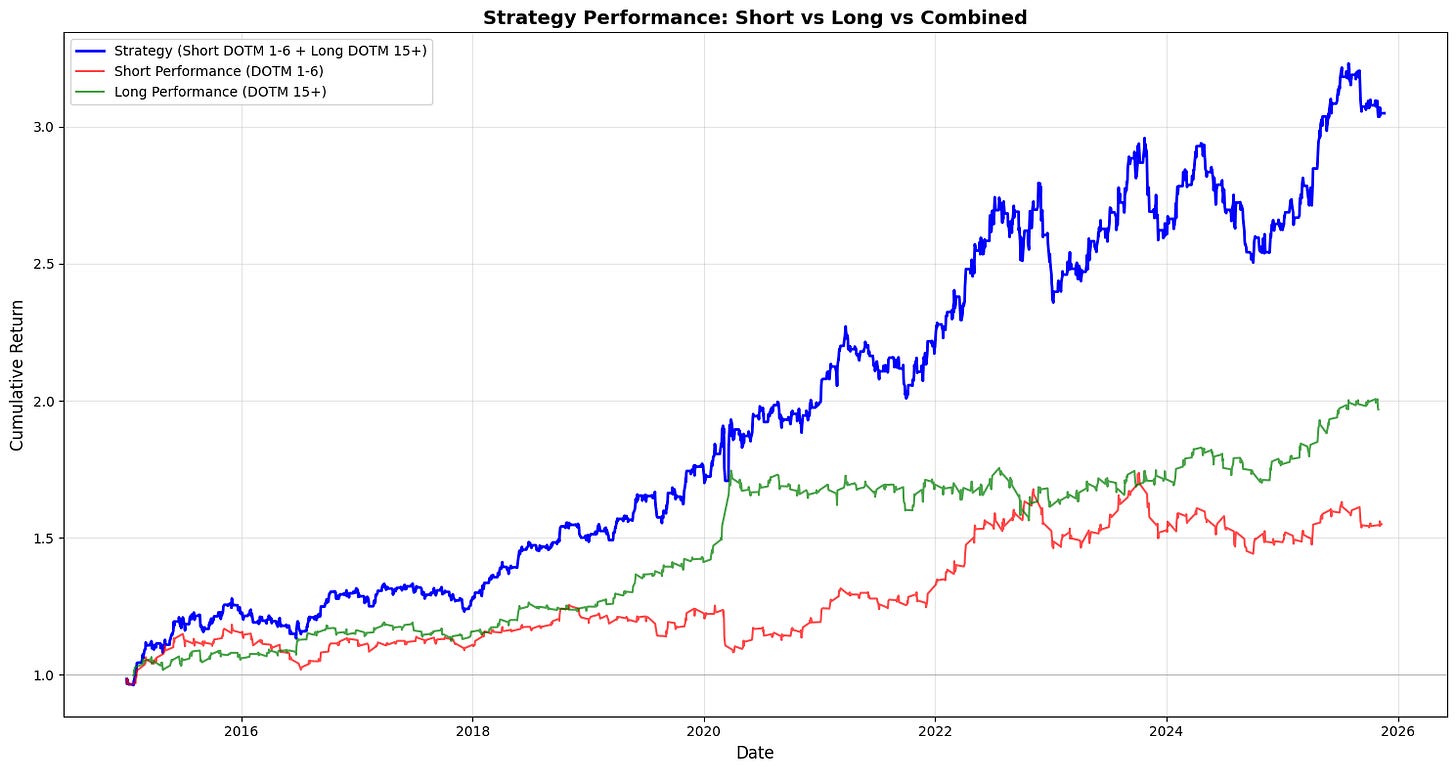

Backtest

Backtest the signal: short at the start of the trading month (close the early-month short around day 7) and go long around mid-month (DOTM ≈ 15) through month end. Compute total and annualized return, annualized volatility, Sharpe ratio, and maximum drawdown.

Plot cumulative performance for the strategy, buy-and-hold, and the short/long legs separately.

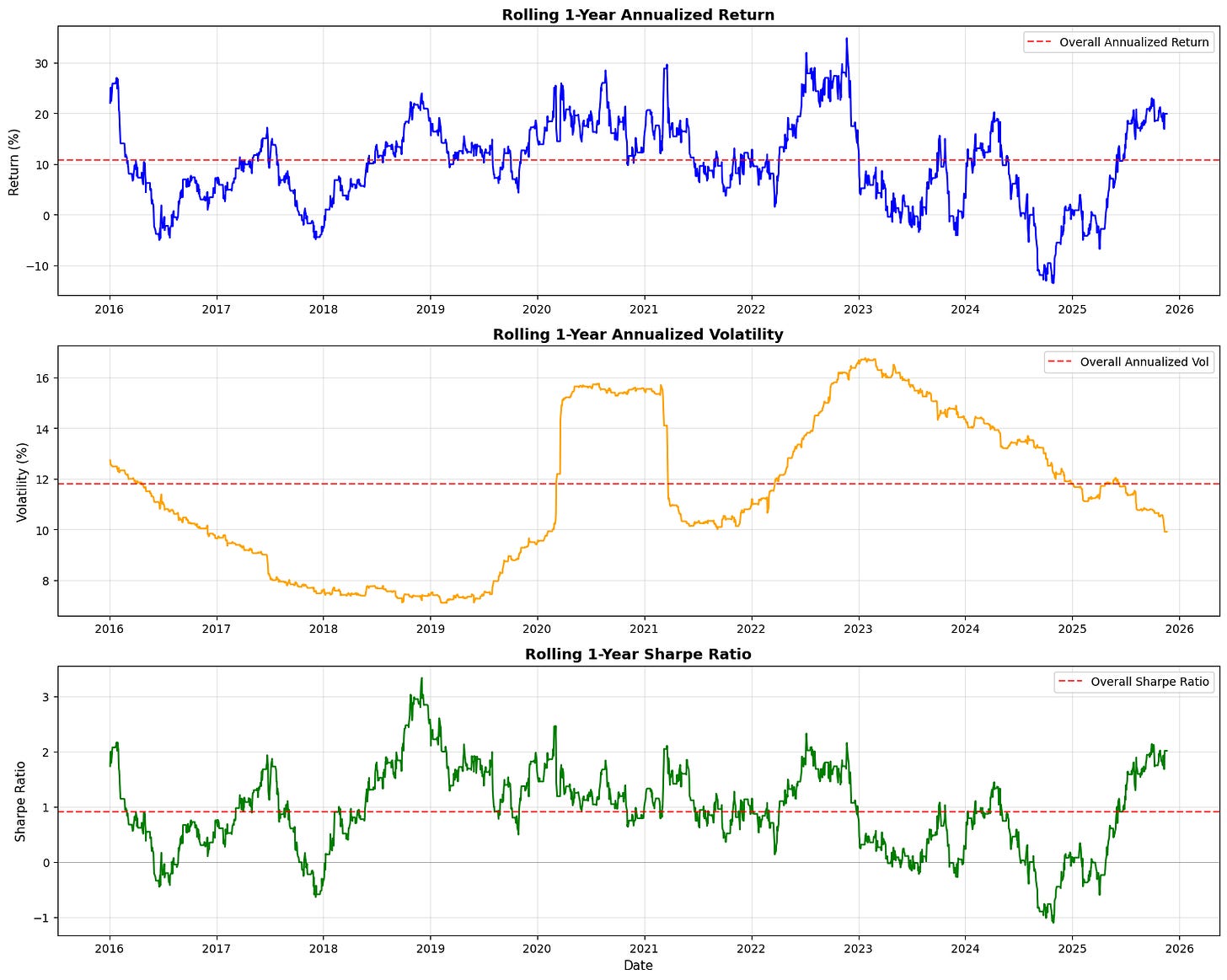

Calculate rolling 1-year metrics (annualized return, volatility, Sharpe) and summarize results.

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

df = pd.read_csv(”C:\\Users\\blazo\\Documents\\Misc\\QJ\\quant-journey\\data\\returns\\returns_TLT.csv”)

df[’Date’] = pd.to_datetime(df[’Date’])

df[’DOM’] = df[’Date’].dt.day

df[’DOTM’] = df.groupby(df[’Date’].dt.to_period(’M’)).cumcount() + 1The snippet loads a CSV of returns and immediately converts the Date column into a true datetime type so downstream temporal operations are reliable. Converting to datetime is necessary here because the next two features use pandas’ .dt accessor and period-based grouping; with a string Date you wouldn’t be able to ask “what day of the month is this?” or group cleanly by calendar month. In the quant context this ensures any calendar-based analysis (seasonality, turn-of-month effects, monthly P&L aggregation) is operating on bona fide timestamps rather than fragile strings.

Next the code derives DOM (day of month) by pulling the calendar day number from each timestamp. DOM is the raw calendar day (1–31) and is useful when you want to study returns tied to calendar dates (for example, end-of-month trade windows, specific-day corporate actions, or dividends that occur on fixed calendar dates). Because DOM is based on the calendar day it does not account for weekends or market holidays; DOM will be the same whether a date is a trading day or not, so use it when you explicitly want calendar-day behavior.

The DOTM column is an ordinal index of the observation within each calendar month: it groups all rows by month (using Date.to_period(‘M’) which collapses the timestamp to a month period) and then uses cumcount() to number rows within that group, adding 1 because cumcount starts at zero. DOTM therefore gives you the “nth trading/day row in this month” — in practice, with daily returns data this corresponds to trading-day number within the month, which is exactly what you need for analyses like “first N trading days” or “compare performance on trading day 1 vs trading day 20” in intramonth strategies. Using to_period(‘M’) ensures grouping is by calendar month boundary (ignoring the day components), so months with different numbers of days are handled consistently.

A few practical notes tied to why these choices matter in quant workflows: the correctness of DOTM relies on the rows being chronologically ordered within each month — if the CSV is not sorted you should sort by Date before grouping to avoid misnumbering. Also, since weekends and holidays are typically absent from return series, DOTM will reflect trading-day ordinal rather than contiguous calendar days, which is usually what you want for signal timing and backtests; but if you intended true calendar-day indices you would need a different approach. Finally, these engineered features make it straightforward to compute conditional statistics (mean return by DOTM, hit-rate by DOM, or whether certain intramonth windows consistently outperform) and to implement calendar-based execution rules or rebalancing logic in downstream quant models.

# Calculate average return for each day of the month

avg_return_dom = df.groupby(’DOM’)[’Return’].mean()

# Calculate average return for each day of the trading month

avg_return_dotm = df.groupby(’DOTM’)[’Return’].mean()

# Create histograms for average returns

fig, (ax1, ax2) = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(15, 5))

# Histogram for Day of Month

ax1.bar(avg_return_dom.index, avg_return_dom.values)

ax1.set_xlabel(’Day of Month’)

ax1.set_ylabel(’Average Return’)

ax1.set_title(’Average Return by Day of Month (DOM)’)

ax1.axhline(y=0, color=’r’, linestyle=’--’, alpha=0.5)

ax1.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# Histogram for Day of Trading Month

ax2.bar(avg_return_dotm.index, avg_return_dotm.values)

ax2.set_xlabel(’Day of Trading Month’)

ax2.set_ylabel(’Average Return’)

ax2.set_title(’Average Return by Day of Trading Month (DOTM)’)

ax2.axhline(y=0, color=’r’, linestyle=’--’, alpha=0.5)

ax2.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

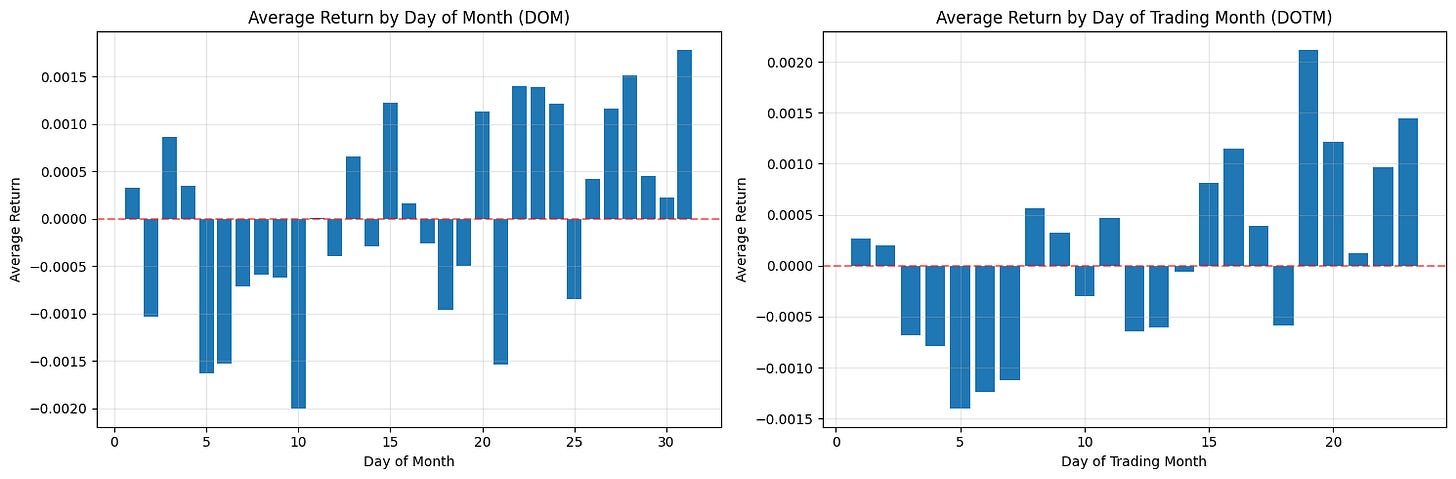

plt.show()This block is performing a simple but important diagnostic for calendar effects: it computes and plots average returns conditioned on two different “day within month” definitions so you can visually inspect whether certain days consistently produce positive or negative returns — a potential tradable edge.

First, the code reduces noise by aggregating returns across observations: avg_return_dom = df.groupby(‘DOM’)[‘Return’].mean() collapses the universe of returns into a single mean for each calendar day-of-month (1–31). The motivation is to reveal persistent calendar-level effects such as turn-of-month, end-of-quarter or tax/holiday-related flows that are tied to calendar dates. Taking the mean is a basic signal-extraction step: random intraday or idiosyncratic noise tends to cancel out across many observations, leaving systematic patterns if they exist. The second grouping, avg_return_dotm = df.groupby(‘DOTM’)[‘Return’].mean(), does the same aggregation but uses the trading-day-within-month index (1..N trading days). DOTM normalizes across months that have different numbers of calendar days and holiday schedules, so it isolates effects tied to the trading-cycle (e.g., “first trading day of the month” or “last trading day”) rather than raw calendar dates.

Next, the code visualizes these two series side-by-side so you can compare their shapes and magnitudes. Plotting them as bar charts makes it easy to see which specific day bins have positive vs negative average returns, and the axhline at y=0 emphasizes the profit/loss baseline. Presenting DOM and DOTM adjacent to each other is deliberate: some effects are calendar-based (DOM) and others are trading-cycle based (DOTM); seeing both helps you decide which is conceptually appropriate for a trading rule. The grid and layout choices are purely for legibility so that you can quickly scan for notable deviations from zero.

A few important practical caveats and why they matter for quant trading: a raw mean can be dominated by outliers or by unequal sample sizes across bins, so you must check counts per bin and the variance within each bin before converting these observations into trading rules. Consider adding error bars (standard error or bootstrap confidence intervals), medians, or winsorization to guard against outliers; consider weighting by volume if larger trades should matter more. Also test statistical significance (t-tests, bootstrap) and control for multiple comparisons — many day-bins means a higher false-positive risk. Verify effects are stable out-of-sample, across different symbols and time periods, and robust to transaction costs, slippage, and liquidity constraints before deploying. Finally, be mindful of data issues that can produce spurious patterns (lookahead, survivorship bias, misaligned corporate actions); ensure DOM/DOTM are computed consistently and that missing bins (e.g., no 31st in some months) are handled explicitly.

In short: this code is a first-pass exploratory step to detect calendar or trading-day seasonality by averaging returns by two different “day” definitions and plotting them for visual inspection. If you find promising signals, the next steps are to quantify significance, control for confounders, test robustness, and simulate realistic P&L with costs before using any signal in a live quant strategy.

# Split data based on DOM (Day of Month)

df[’DOM_Group’] = pd.cut(df[’DOM’], bins=[0, 5, 26, 31], labels=[’First 5 Days’, ‘Middle Days’, ‘Last 5 Days’])

# Split data based on DOTM (Day of Trading Month)

df[’DOTM_Group’] = pd.cut(df[’DOTM’], bins=[0, 5, 18, 23], labels=[’First 5 Days’, ‘Middle Days’, ‘Last 5 Days’])

# Calculate average returns for each group

dom_group_returns = df.groupby(’DOM_Group’, observed=True)[’Return’].mean()

dotm_group_returns = df.groupby(’DOTM_Group’, observed=True)[’Return’].mean()

# Create histograms for grouped returns

fig, (ax1, ax2) = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(15, 5))

# Histogram for DOM Groups

ax1.bar(range(len(dom_group_returns)), dom_group_returns.values)

ax1.set_xticks(range(len(dom_group_returns)))

ax1.set_xticklabels(dom_group_returns.index)

ax1.set_xlabel(’DOM Group’)

ax1.set_ylabel(’Average Return’)

ax1.set_title(’Average Return by DOM Group’)

ax1.axhline(y=0, color=’r’, linestyle=’--’, alpha=0.5)

ax1.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# Histogram for DOTM Groups

ax2.bar(range(len(dotm_group_returns)), dotm_group_returns.values)

ax2.set_xticks(range(len(dotm_group_returns)))

ax2.set_xticklabels(dotm_group_returns.index)

ax2.set_xlabel(’DOTM Group’)

ax2.set_ylabel(’Average Return’)

ax2.set_title(’Average Return by DOTM Group’)

ax2.axhline(y=0, color=’r’, linestyle=’--’, alpha=0.5)

ax2.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

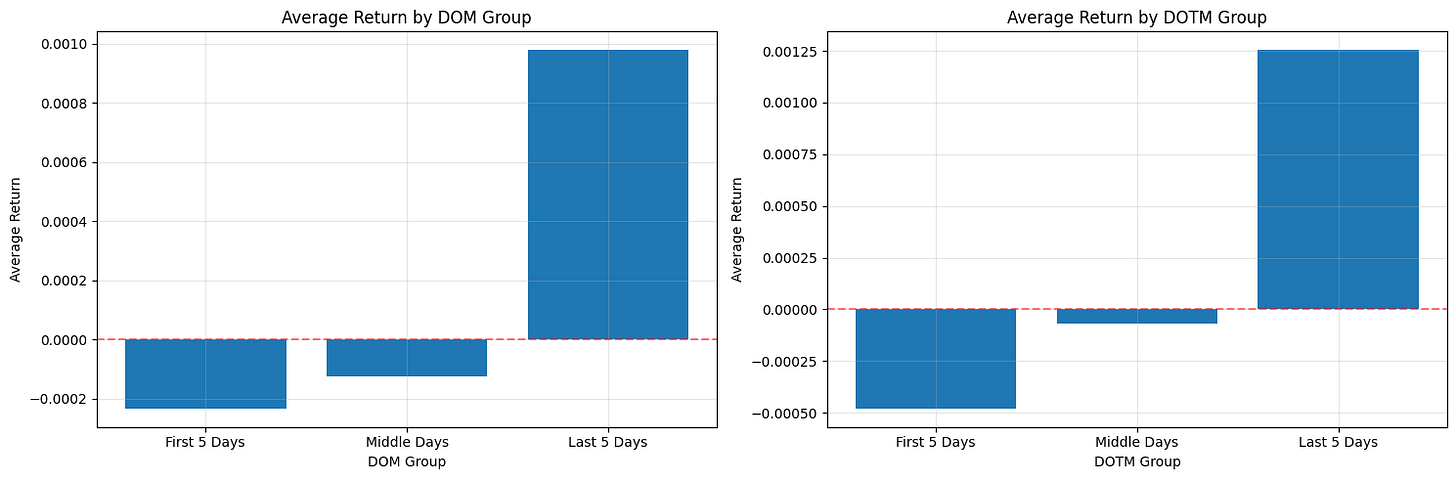

plt.show()This block is designed to surface simple calendar-driven return patterns that you can exploit or control for in a quant trading strategy. It first discretizes two different day-of-period features into coarse buckets: DOM (calendar Day Of Month) and DOTM (Day Of Trading Month). The pd.cut calls create categorical bins with three labels — “First 5 Days”, “Middle Days”, and “Last 5 Days” — using the numeric bin edges you provided. Note the semantics of pd.cut: with the default right=True, a bin like (0, 5] will contain days 1–5 if your day numbering starts at 1. This discretization is purposeful: we want to compress daily noise into a few interpretable regimes where behavioral or institutional effects (e.g., month-begin flows, mid-month rebalancing, end-of-month window dressing) may produce systematic return differences.

After creating those categorical groups, the code computes the mean return within each bucket via groupby(…)[‘Return’].mean(). The groupby uses observed=True which tells pandas to only include categories actually present in the data in the result (useful when your categories are from a Categorical dtype and you don’t want empty categories cluttering the output). Using the mean as the summary metric is a pragmatic choice: it gives a simple, directionally intuitive metric of whether a bucket is net positive or negative on average. That said, the mean is sensitive to outliers and uneven sample sizes across buckets; for production analyses you’ll want to complement this with counts, medians, and confidence intervals (or bootstrap t-stats) to judge statistical robustness before acting on any signal.

The visualization maps those aggregated means to side-by-side bar charts so you can compare DOM and DOTM effects visually. Each axis uses a simple integer x-position (range(len(…))) and then replaces tick labels with the categorical group names so the bars align with the interpreted buckets. A red dashed horizontal line at y=0 is included as an explicit reference for sign (positive vs. negative average return), and faint gridlines make small differences easier to read. Tight layout is applied to avoid label overlap in the figure. This plotting choice emphasizes magnitude and sign, which is usually sufficient for an initial exploratory check of calendar effects.

There are a few practical caveats tied to the “why” behind these decisions. Because your bin edges differ between DOM and DOTM, ensure those ranges actually match the distribution of values in your dataset: pd.cut will produce NaNs for values outside the provided bins, and the DOTM bins ending at 23 suggest you may be excluding later trading days if DOTM can reach higher values. Also check bucket sample sizes — a large mean driven by a handful of observations is unreliable for trading decisions. Consider swapping or augmenting mean with median, trimmed mean, or winsorization to reduce outlier influence, and add counts and standard errors to the plot or table to evaluate significance before deploying a timing rule.

In terms of quant-trading implications: this code is a diagnostic step to detect calendar seasonality that could justify timing overlays, regime-aware position sizing, or risk-management rules. If you observe a consistent, statistically significant pattern (for example, persistently positive returns in the first five trading days), you could implement a lightweight timing signal that increases exposure in that regime — but only after backtesting with transaction costs, conditioning on other known factors, and confirming the effect out-of-sample.

# Calculate cumulative mean log returns by DOM

cumulative_mean_dom = df.groupby(’DOM’)[’LogReturn’].mean().cumsum()

# Calculate cumulative mean log returns by DOTM

cumulative_mean_dotm = df.groupby(’DOTM’)[’LogReturn’].mean().cumsum()

# Create plots for cumulative mean log returns

fig, (ax1, ax2) = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(15, 5))

# Plot for Day of Month

ax1.plot(cumulative_mean_dom.index, cumulative_mean_dom.values, marker=’o’, linewidth=2)

ax1.set_xlabel(’Day of Month’)

ax1.set_ylabel(’Cumulative Mean Log Return’)

ax1.set_title(’Cumulative Mean Log Returns by Day of Month (DOM)’)

ax1.axhline(y=0, color=’r’, linestyle=’--’, alpha=0.5)

ax1.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# Plot for Day of Trading Month

ax2.plot(cumulative_mean_dotm.index, cumulative_mean_dotm.values, marker=’o’, linewidth=2)

ax2.set_xlabel(’Day of Trading Month’)

ax2.set_ylabel(’Cumulative Mean Log Return’)

ax2.set_title(’Cumulative Mean Log Returns by Day of Trading Month (DOTM)’)

ax2.axhline(y=0, color=’r’, linestyle=’--’, alpha=0.5)

ax2.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

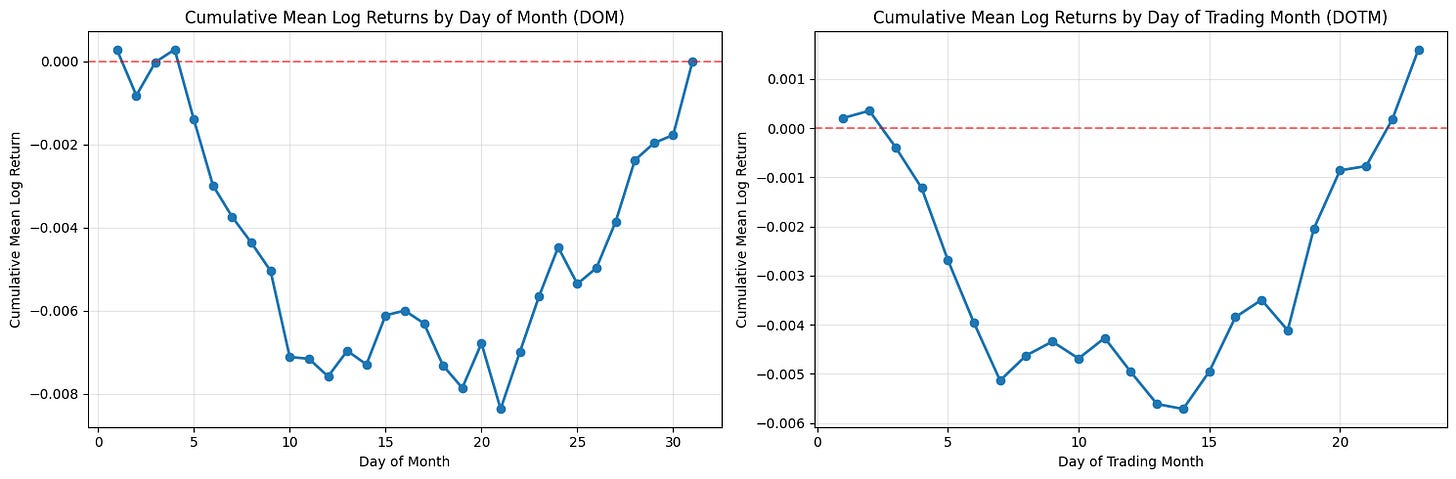

plt.show()This block takes per-row log returns and converts them into two simple, visual seasonality diagnostics: one indexed by calendar day-of-month (DOM) and one by trading-day-of-month (DOTM). The first step groups the returns by the chosen bucket (DOM or DOTM) and computes the mean log return for each bucket. Averaging within buckets gives a single summary statistic per day index — effectively the expected log-return when that bucket occurs. The code then runs a cumulative sum over those bucket means. Because these are log returns, summing them across successive buckets corresponds to the log of a compounded return across those buckets, so cumsum is a natural way to show the accumulated directional effect as you move through the month.

Using log returns and cumsum is purposeful: log returns add under composition, so the plotted cumulative mean is interpretable as the expected aggregate log performance across the sequence of day buckets. That makes it easier to reason about persistent small biases (for example, if the first five trading days each have slightly positive mean log returns, their sum will show a clear upward drift). If you wanted multiplicative returns instead, you would exponentiate the cumsum to get the expected gross return multiplier over the sequence.

The distinction between DOM and DOTM matters for quant trading signals. DOM groups by calendar date (1–31), which can reveal calendar-driven effects (end-of-month window dressing, payroll dates, etc.) but is influenced by weekends and holidays. DOTM groups by trading-day index inside a month (1st trading day, 2nd trading day, …), which normalizes away non-trading days and is usually more directly actionable for intramonth timing because it reflects the sequence of tradable opportunities. Be aware that group sizes vary: some DOM buckets will have fewer observations (e.g., 31st), and DOTM buckets may have heterogeneous sample counts across months — the code uses simple means and does not weight or adjust for unequal sample sizes.

Before plotting, ensure the bucket indices are ordered; groupby typically returns sorted group keys, but you should explicitly sort if custom indices are possible. The visualization plots each cumulative-mean series with markers and a line so you can see both discrete bucket jumps and the overall trajectory. The horizontal zero line highlights whether cumulative bias crosses into net positive or negative territory; small oscillations around zero indicate no persistent intramonth edge, while monotonic movement suggests a potentially exploitable seasonality. Grid and layout choices are purely presentational but help with reading small differences across buckets.

A few practical caveats for using these outputs in a trading strategy: the mean-based cumsum does not provide uncertainty bounds or significance testing, so apparent edges may be noise — you should overlay standard errors, bootstrap confidence intervals, or t-tests and verify effect stability out of sample. Also check bucket sample counts and consider winsorizing or trimming outliers; transaction costs, liquidity, and market impact will materially affect whether a small mean edge is tradable. Finally, confirm there is no look-ahead or survivorship bias in the input dataframe, and consider repeating the analysis on rolling windows to test time stability before embedding any signal into execution logic.

Short actionable suggestions: explicitly sort the indices before plotting, annotate or plot bucket counts to see where sample sizes are thin, add confidence bands (e.g., +/- standard error) around the cumulative curve, and convert cumsum to exp(cumsum) if you need to present multiplicative returns to stakeholders or for position-sizing calculations. These steps help turn the plotted diagnostic into a robust input for intramonth timing decisions in a quant strategy.

Backtest

Guidelines for evaluating strategies using historical data.

# Create a copy of the dataframe for backtesting

backtest_df = df.copy()

# Initialize position and portfolio value columns

backtest_df[’Position’] = 0 # 0 = no position, -1 = short, 1 = long

backtest_df[’Strategy_Return’] = 0.0

# Define the trading strategy based on DOTM

# Short from day 1 to day 6 (close on day 7)

# Long from day 15 to end of month

backtest_df.loc[(backtest_df[’DOTM’] >= 1) & (backtest_df[’DOTM’] <= 6), ‘Position’] = -1

backtest_df.loc[backtest_df[’DOTM’] >= 15, ‘Position’] = 1

# Calculate strategy returns (position * return)

backtest_df[’Strategy_Return’] = backtest_df[’Position’] * backtest_df[’Return’]

# Calculate cumulative returns

backtest_df[’Cumulative_Strategy_Return’] = (1 + backtest_df[’Strategy_Return’]).cumprod()

# Calculate performance metrics

total_return = backtest_df[’Cumulative_Strategy_Return’].iloc[-1] - 1

total_profit = total_return * 100 # in percentage

# Calculate annualized return

n_years = (backtest_df[’Date’].iloc[-1] - backtest_df[’Date’].iloc[0]).days / 365.25

annualized_return = (1 + total_return) ** (1 / n_years) - 1

# Calculate annualized volatility

annual_vol = backtest_df[’Strategy_Return’].std() * np.sqrt(252)

# Calculate Sharpe ratio (assuming 0% risk-free rate)

annual_sharpe = annualized_return / annual_vol if annual_vol != 0 else 0

# Calculate maximum drawdown

cumulative_returns = backtest_df[’Cumulative_Strategy_Return’]

running_max = cumulative_returns.cummax()

drawdown = (cumulative_returns - running_max) / running_max

max_drawdown = drawdown.min()

# Print results

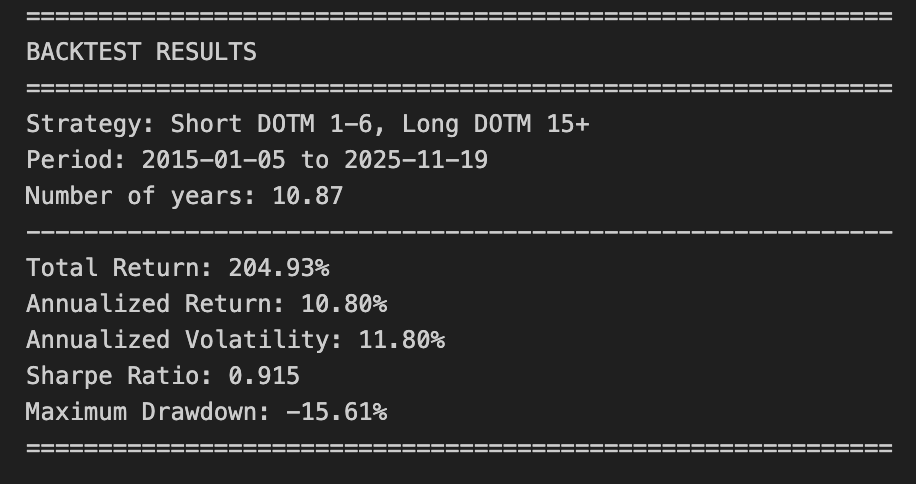

print(”=” * 60)

print(”BACKTEST RESULTS”)

print(”=” * 60)

print(f”Strategy: Short DOTM 1-6, Long DOTM 15+”)

print(f”Period: {backtest_df[’Date’].iloc[0].date()} to {backtest_df[’Date’].iloc[-1].date()}”)

print(f”Number of years: {n_years:.2f}”)

print(”-” * 60)

print(f”Total Return: {total_return * 100:.2f}%”)

print(f”Annualized Return: {annualized_return * 100:.2f}%”)

print(f”Annualized Volatility: {annual_vol * 100:.2f}%”)

print(f”Sharpe Ratio: {annual_sharpe:.3f}”)

print(f”Maximum Drawdown: {max_drawdown * 100:.2f}%”)

print(”=” * 60)This block implements a simple rule-based backtest that shorts the asset during the first trading days of each month (DOTM 1–6) and goes long from the middle of the month onward (DOTM >= 15). It starts by making a defensive copy of the input dataframe so the original market data remains unchanged for other analyses; that copy becomes the working dataset for all subsequent calculations.

Next it creates two new columns to hold the trading state and profit-and-loss: a discrete Position column with values -1, 0, or +1, and a Strategy_Return column initialized to zero. The code then assigns positions deterministically from the DOTM field: set Position = -1 when DOTM is between 1 and 6 (short at month-start), set Position = +1 when DOTM >= 15 (long from mid-month onward), and leave Position = 0 otherwise. The choice to use DOTM windows defines the strategy’s regime timing — days 7–14 are intentionally neutral — and those windows are applied across every row to produce a time series of exposures.

With exposure defined, the Strategy_Return for each row is computed as Position * Return. Here Return is expected to be the asset’s simple period return; multiplying by the position turns that into the strategy’s realized return for the period (positive if returns align with the position, negative if they don’t). This approach assumes the position is held through the period represented by Return and that returns scale linearly with position (i.e., no leverage or position sizing multipliers beyond ±1).

Cumulative performance is then built via compounding: the code forms (1 + Strategy_Return) and takes a cumulative product. This produces a growth-of-1 time series that represents the portfolio value trajectory under continuous compounding of discrete period returns, which is appropriate when you want to observe total performance over time including compounding effects.

The code extracts a set of common performance metrics from that trajectory. Total return is the final cumulative value minus one; annualized return is obtained by treating total return as a multi-year geometric return and raising (1 + total_return) to the power 1 / n_years, where n_years is computed as the calendar-day span divided by 365.25. Annualized volatility is estimated by taking the standard deviation of the daily Strategy_Return series and scaling by sqrt(252) to annualize under the conventional trading-day assumption. The Sharpe ratio is then computed as annualized_return / annual_vol, implicitly treating the risk-free rate as zero; the code guards against division by zero by returning zero if annual_vol is zero.

Maximum drawdown is computed from the cumulative strategy curve by tracking the running maximum and measuring the percentage drop from that peak to the current value; the most negative of those values is the max drawdown, which captures the strategy’s worst peak-to-trough loss over the backtest. Finally, the script prints a concise summary including period, years, total and annualized returns, annualized volatility, Sharpe, and max drawdown.

A few practical caveats implicit in these choices: returns are treated as simple returns and positions are applied directly to those returns (no transaction costs, slippage, overnight risk adjustments, or explicit entry/exit timing corrections are included), the annualization uses calendar span for years and 252 for volatility which can mismatch if your data includes non-standard trading frequencies, and position logic assumes DOTM is correctly aligned with returns (you may need to shift positions by one row if signals are generated at close and positions are entered the next open). Depending on the use case, consider adding transaction cost modeling, position sizing, and careful alignment of signal and execution timestamps before assessing real-world feasibility.

# Calculate separate performance for short and long positions

short_df = backtest_df[backtest_df[’Position’] == -1].copy()

long_df = backtest_df[backtest_df[’Position’] == 1].copy()

# Calculate cumulative returns for short and long separately

short_df[’Cumulative_Short_Return’] = (1 + short_df[’Strategy_Return’]).cumprod()

long_df[’Cumulative_Long_Return’] = (1 + long_df[’Strategy_Return’]).cumprod()

# Plot the performance

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(15, 8))

# Plot strategy performance

ax.plot(backtest_df[’Date’], backtest_df[’Cumulative_Strategy_Return’],

label=’Strategy (Short DOTM 1-6 + Long DOTM 15+)’, linewidth=2, color=’blue’)

# Plot short performance

ax.plot(short_df[’Date’], short_df[’Cumulative_Short_Return’],

label=’Short Performance (DOTM 1-6)’, linewidth=1.5, color=’red’, alpha=0.7)

# Plot long performance

ax.plot(long_df[’Date’], long_df[’Cumulative_Long_Return’],

label=’Long Performance (DOTM 15+)’, linewidth=1.5, color=’green’, alpha=0.7)

ax.set_xlabel(’Date’, fontsize=12)

ax.set_ylabel(’Cumulative Return’, fontsize=12)

ax.set_title(’Strategy Performance: Short vs Long vs Combined’, fontsize=14, fontweight=’bold’)

ax.legend(loc=’best’, fontsize=10)

ax.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

ax.axhline(y=1, color=’black’, linestyle=’-’, alpha=0.3, linewidth=0.5)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()This block takes the backtest output and separates, visualizes, and compares the compounding performance of the short and long legs so you can attribute the combined strategy P&L to each side over time.

First, the code isolates the lifecycle records for the short and long legs by filtering the backtest dataframe on the Position column (Position == -1 for shorts and == 1 for longs). We make explicit copies to avoid chained-assignment issues and to ensure subsequent column additions don’t affect the original dataframe unexpectedly. This split is driven by the business rule that DOTM 1–6 exposures are treated as the short leg and DOTM 15+ exposures as the long leg; separating the rows lets us compute each leg’s realized performance independently, which is essential for attribution and risk diagnostics in a multi-leg options strategy.

Next, cumulative returns for each leg are computed with (1 + Strategy_Return).cumprod(). Using cumprod models compounding correctly — it rolls forward the growth of a $1 (or 100%) base investment by multiplying period returns rather than summing them, so you see the true compounded P&L path of each leg. This works whether Strategy_Returns are positive or negative (short returns will be negative when they lose money), so the resulting series shows the time evolution of capital if you had only run that leg. Note that the combined strategy line is plotted from backtest_df[‘Cumulative_Strategy_Return’], which implies the combined cumulative series was precomputed earlier; plotting all three on the same axes allows visual inspection of how much each leg contributes to divergence from the combined path.

The plotting section then lays out the visual story: a larger, thicker blue line for the full strategy (to emphasize the primary metric), and thinner, semi-transparent red and green lines for the short and long legs respectively. The baseline y=1 is drawn so you can immediately see when each leg or the combined strategy has broken even relative to the starting capital. Labels, legend, grid and a tight layout are applied to make trends and crossovers clear at a glance. Alpha and linewidth choices are purely presentational but purposeful: the combined strategy is highlighted as the main outcome while the legs are shown as supportive, slightly de-emphasized traces.

A few practical notes relevant to quant backtesting: because the code filters rows by Position, any dates where the strategy is flat (Position == 0 or missing) will not appear in the leg-specific curves — this can create discontinuities if you expect continuous time series. If you want continuous leg-level curves that hold prior capital forward when flat, you should reindex to the full date index and forward-fill or explicitly align on the same timeline as the combined series. Also confirm that Strategy_Return already reflects trade-level signs (i.e., short returns are recorded from the perspective of the strategy, not instrument price moves); otherwise you must flip signs before compounding. Finally, remember to incorporate transaction costs, borrow costs for shorts, and differing notional sizing across legs before drawing conclusions — the visual attribution is only as accurate as the underlying return series.

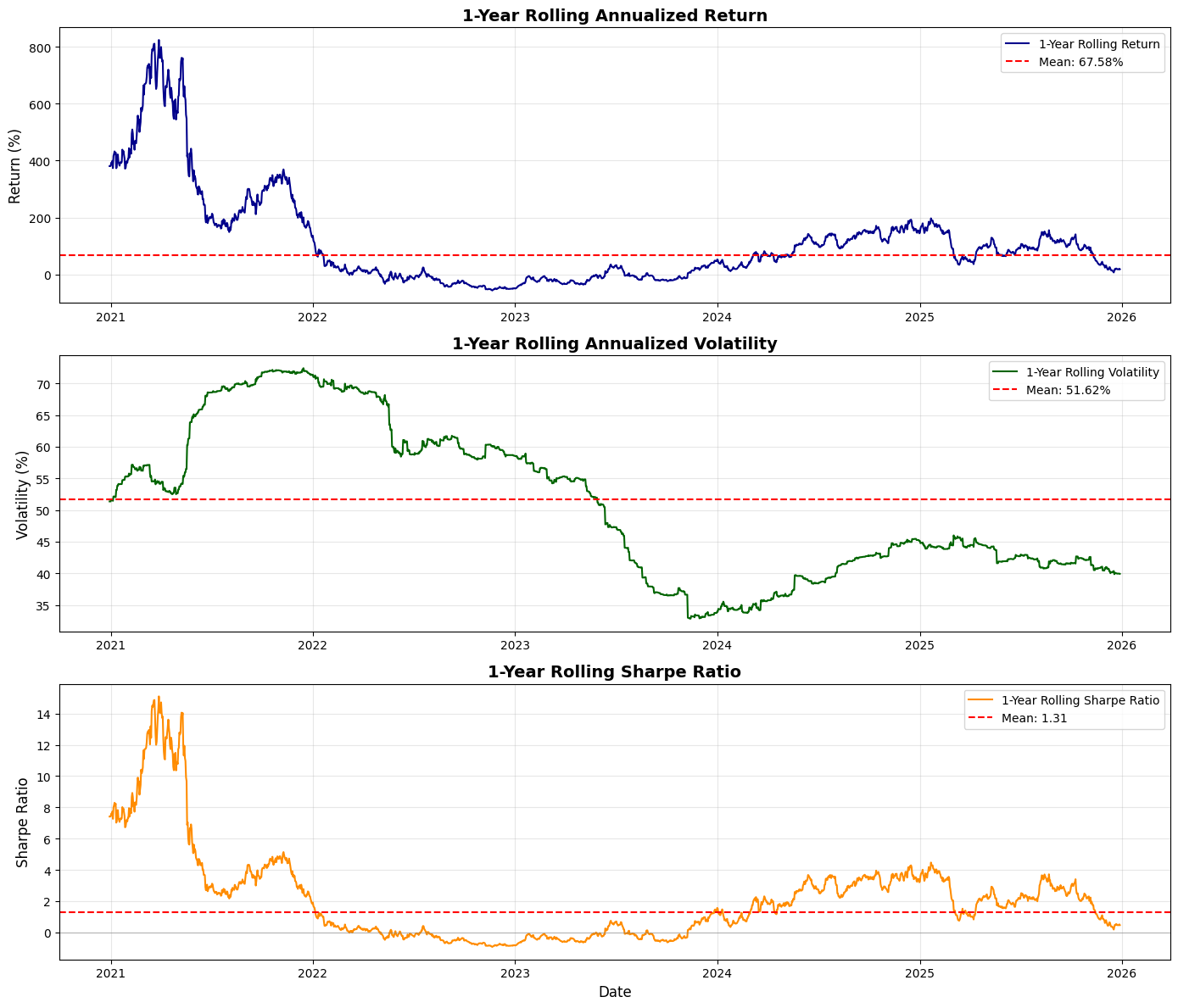

# Calculate rolling metrics with a 252-day window (1 year)

window = 252

# Calculate rolling annualized return

backtest_df[’Rolling_Return’] = backtest_df[’Strategy_Return’].rolling(window=window).apply(

lambda x: (1 + x).prod() ** (252 / len(x)) - 1 if len(x) == window else np.nan

)

# Calculate rolling annualized volatility

backtest_df[’Rolling_Vol’] = backtest_df[’Strategy_Return’].rolling(window=window).std() * np.sqrt(252)

# Calculate rolling Sharpe ratio

backtest_df[’Rolling_Sharpe’] = backtest_df[’Rolling_Return’] / backtest_df[’Rolling_Vol’]

# Create plots for rolling metrics

fig, (ax1, ax2, ax3) = plt.subplots(3, 1, figsize=(15, 12))

# Plot rolling annualized return

ax1.plot(backtest_df[’Date’], backtest_df[’Rolling_Return’] * 100, linewidth=1.5, color=’blue’)

ax1.axhline(y=annualized_return * 100, color=’red’, linestyle=’--’, alpha=0.7, label=’Overall Annualized Return’)

ax1.set_ylabel(’Return (%)’, fontsize=11)

ax1.set_title(’Rolling 1-Year Annualized Return’, fontsize=13, fontweight=’bold’)

ax1.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

ax1.legend()

# Plot rolling annualized volatility

ax2.plot(backtest_df[’Date’], backtest_df[’Rolling_Vol’] * 100, linewidth=1.5, color=’orange’)

ax2.axhline(y=annual_vol * 100, color=’red’, linestyle=’--’, alpha=0.7, label=’Overall Annualized Vol’)

ax2.set_ylabel(’Volatility (%)’, fontsize=11)

ax2.set_title(’Rolling 1-Year Annualized Volatility’, fontsize=13, fontweight=’bold’)

ax2.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

ax2.legend()

# Plot rolling Sharpe ratio

ax3.plot(backtest_df[’Date’], backtest_df[’Rolling_Sharpe’], linewidth=1.5, color=’green’)

ax3.axhline(y=annual_sharpe, color=’red’, linestyle=’--’, alpha=0.7, label=’Overall Sharpe Ratio’)

ax3.axhline(y=0, color=’black’, linestyle=’-’, alpha=0.3, linewidth=0.5)

ax3.set_xlabel(’Date’, fontsize=11)

ax3.set_ylabel(’Sharpe Ratio’, fontsize=11)

ax3.set_title(’Rolling 1-Year Sharpe Ratio’, fontsize=13, fontweight=’bold’)

ax3.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

ax3.legend()

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()This block computes and visualizes time-varying performance metrics for a trading strategy using a one-year (252 trading day) rolling window so you can see how returns, risk, and risk-adjusted performance evolve over time. The high-level goal is to move beyond single aggregate numbers and detect regime changes, drawdown periods, or improving/declining performance that would inform position sizing, risk limits, or strategy retirement decisions.

First, the code defines a 252-day window and then builds a rolling annualized return. For each full window it compounds the daily strategy returns by taking the product of (1 + daily_return) and annualizing that cumulative growth with the exponent 252 / len(x). The len(x) == window check ensures you only compute the annualized figure when you have a complete one-year sample (otherwise you set NaN) — this avoids artificially inflating or misrepresenting a partial-period annualization. Note this approach assumes the series contains simple (period) returns; if you were using log returns you would sum and exponentiate instead. Also, using product((1 + x)) directly captures geometric compounding, which is what you want for realized return over multiple periods.

Next, the code computes a rolling annualized volatility by taking the sample standard deviation over each 252-day window and scaling it by sqrt(252). This uses the usual square-root-of-time rule to convert daily volatility to an annualized figure; the underlying assumption is i.i.d. or at least that scaling is a reasonable approximation over the window. Be aware of nuances: rolling.std() uses pandas’ default degrees-of-freedom (ddof) behavior which affects small-sample bias and how NaNs are handled, and missing or irregularly spaced dates can distort the interpretation because the window is row-count based rather than calendar-time based.

The rolling Sharpe is then computed as the ratio of the rolling annualized return to the rolling annualized volatility. This yields a time series of risk-adjusted performance. Two important practical caveats: first, this formula implicitly treats the returns as excess returns (i.e., already net of a risk-free rate); if they are raw returns you should subtract an appropriate risk-free rate (or better, a time series of short-rates) before forming the Sharpe. Second, dividing by volatility can produce very large or undefined values if volatility is near zero or NaN, so it’s common in production code to guard or clip volatility to avoid spurious infinite Sharpe values.

Finally, the code creates three stacked plots (return, volatility, Sharpe) to visualize these rolling metrics. Each plot multiplies the return/volatility series by 100 to show percentages, draws a horizontal dashed red line representing the overall (full-sample) annualized metric for easy reference, and includes basic labeling and grids so you can visually compare short-term dynamics to the long-run average. Using the Date column for the x-axis is fine but remember the rolling window was row-based; if your timestamps contain gaps (weekends, holidays, missing days), consider a time-based rolling window (e.g., 252 trading-day calendar approximation or rolling with an offset) or ensure the DataFrame only contains trading days. Also note a performance consideration: the rolling.apply with a Python lambda is easy to reason about but not the fastest for large datasets — you can vectorize the annualized return via rolling sum of log(1+returns) or use optimized libraries if speed matters.

In short: this code produces a clear, geometrically compounded, one-year rolling view of return, volatility, and Sharpe to monitor how the strategy’s realized performance and risk profile change over time, while leaving a few practical knobs you’ll likely want to tighten for production: risk-free adjustment, NaN/zero-vol handling, choice of return type (simple vs log), and possibly more efficient vectorized computation or calendar-aware rolling windows.

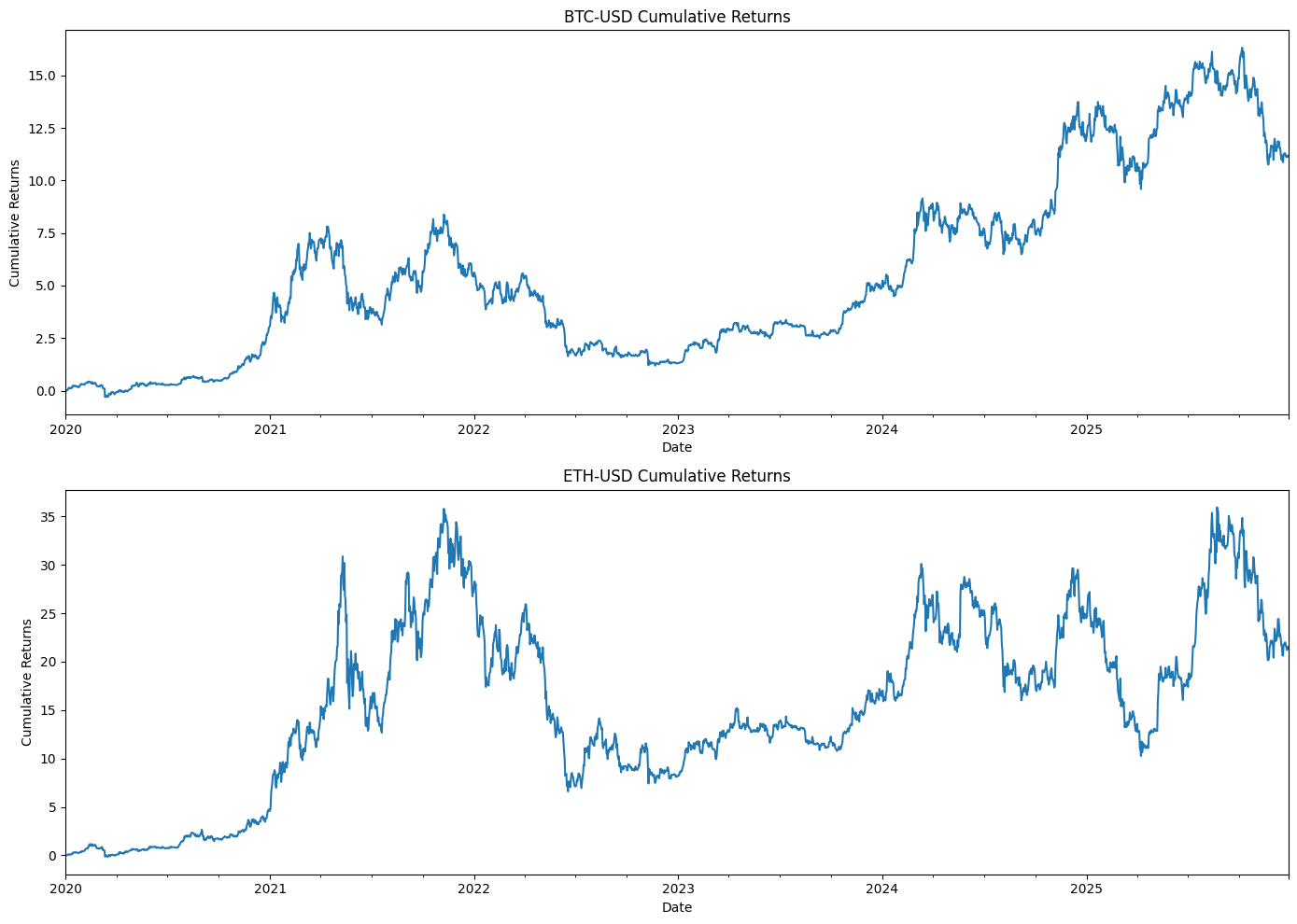

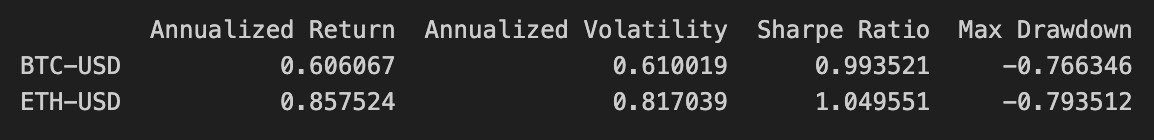

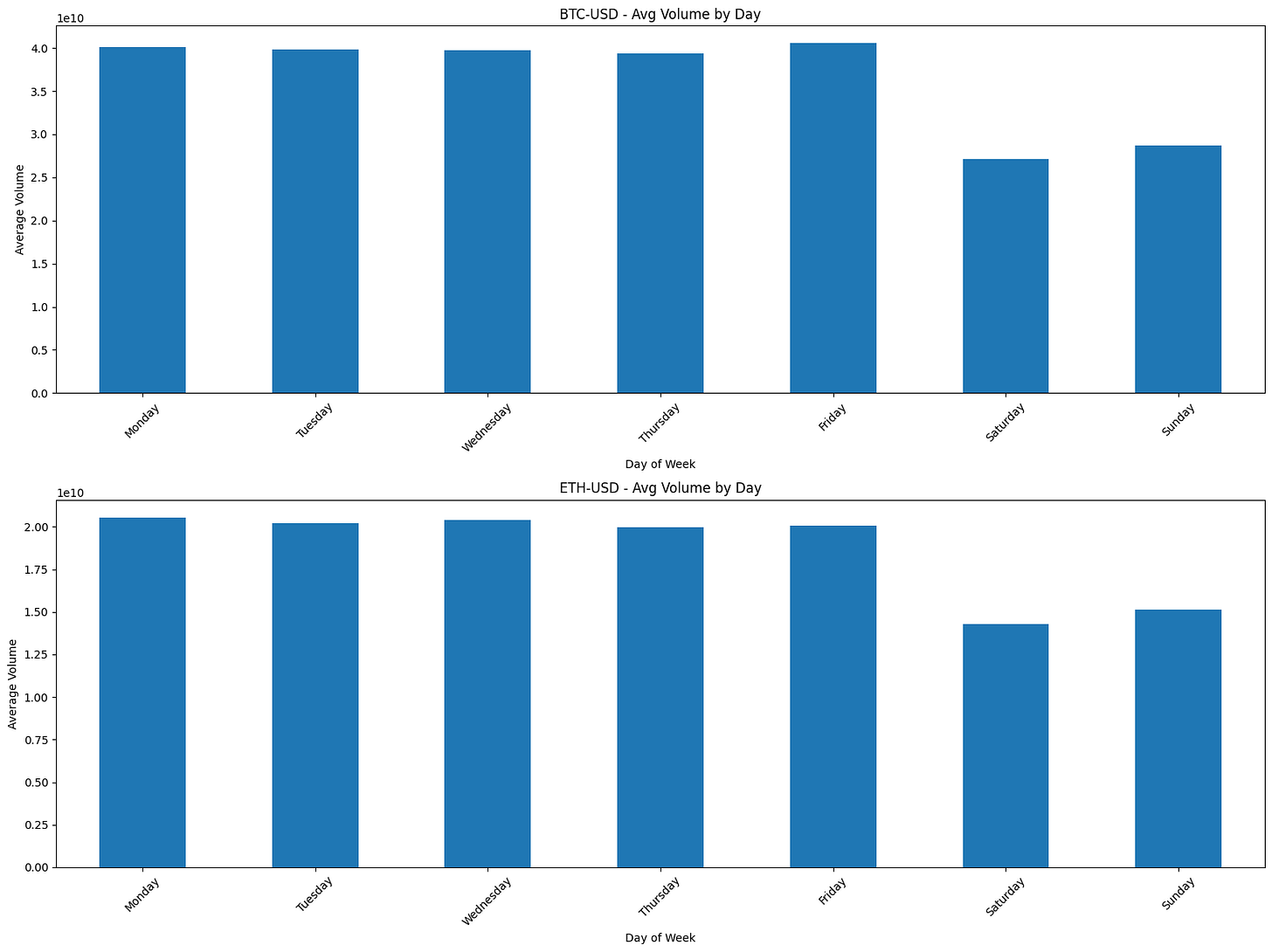

Risk Premia Harvesting — Buy & Hold Strategy

Overview

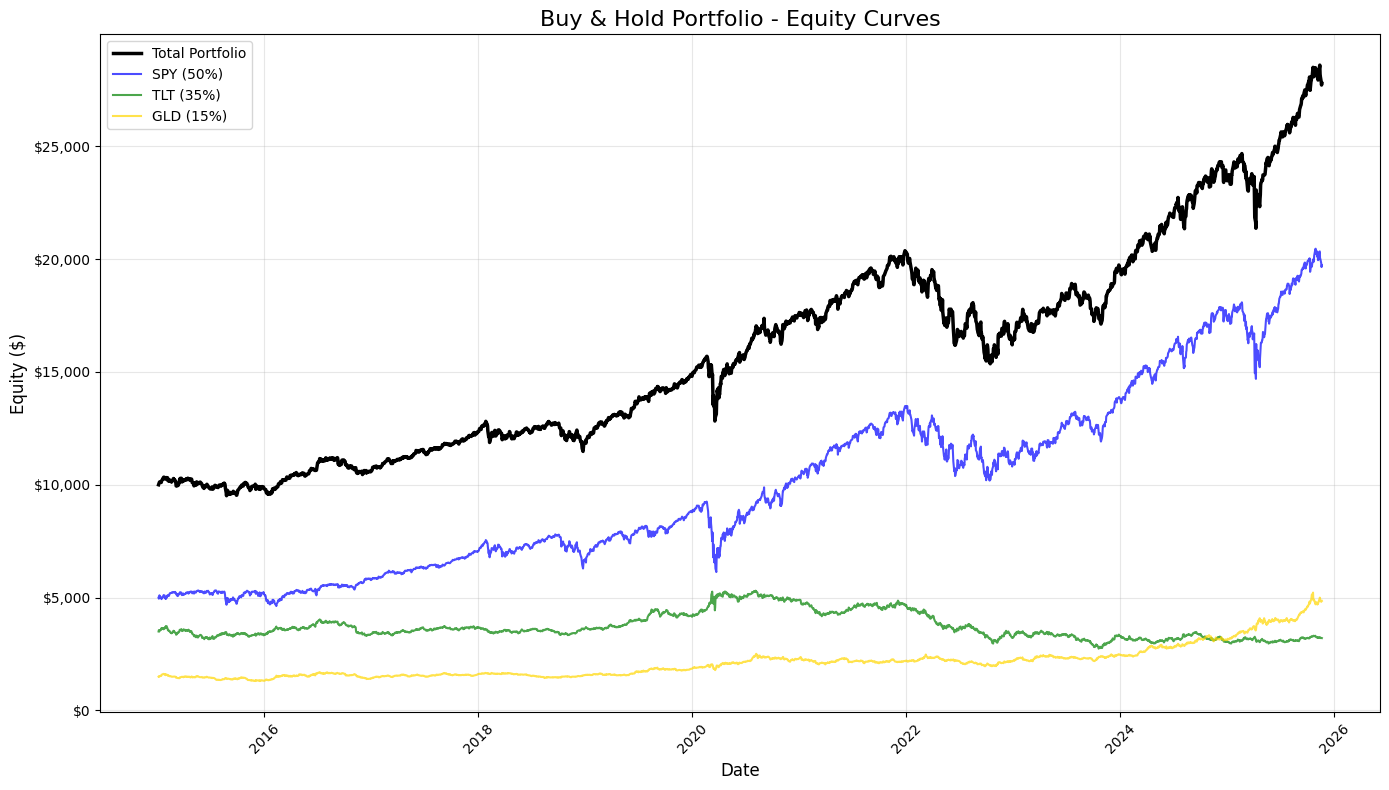

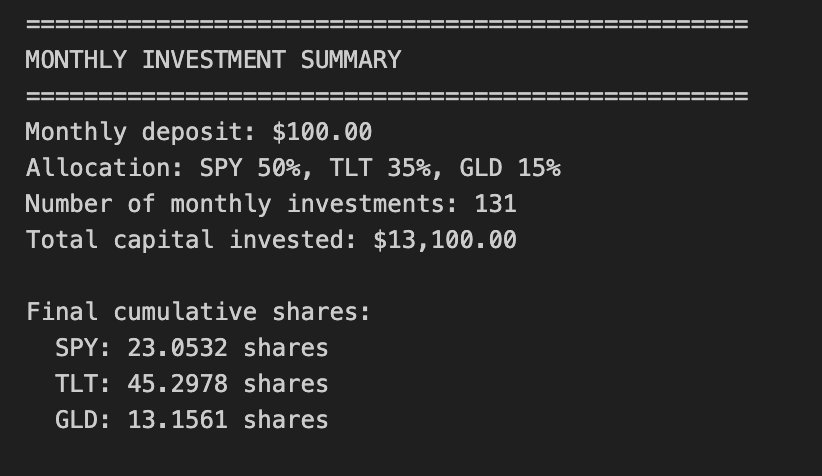

This notebook implements a simple buy-and-hold strategy designed to capture risk premia from a diversified portfolio. The method is straightforward: buy the portfolio assets at the start of the period and hold them for the entire horizon (approximately 10 years) without rebalancing.

Portfolio composition:

SPY (S&P 500 ETF): 50%

TLT (Long-term Treasury ETF): 35%

GLD (Gold ETF): 15%

Initial capital: $10,000.00

Target outputs

Performance metrics

Annualized return

Annualized volatility

Sharpe ratio

Maximum drawdown

Visualizations

Equity curves (total portfolio and individual assets)

1-year rolling annualized return

1-year rolling annualized volatility

1-year rolling Sharpe ratio

Implementation steps

1. Data acquisition

Load historical price data for SPY, TLT, and GLD.

2. Data preparation

Remove rows with missing data.

Ensure all tickers share a common date index.

3. Portfolio initialization

Set initial capital and asset weights.

Select the first trading date.

Calculate dollar allocation per asset.

Determine the number of shares to purchase for each asset.

4. Equity curve construction

Calculate daily equity for each asset.

Compute total portfolio equity.

Consolidate results into a single DataFrame.

5. Returns calculation

Compute daily returns for the portfolio.

Compute daily returns for each individual asset.

6. Performance statistics

Calculate annualized return.

Calculate annualized volatility.

Calculate the Sharpe ratio.

Calculate maximum drawdown.

7. Static visualizations

Plot all equity curves on a single chart.

8. Rolling performance analysis

Generate a 1-year rolling annualized return chart.

Generate a 1-year rolling annualized volatility chart.

Generate a 1-year rolling Sharpe ratio chart.

# Imports

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# 1. Data Acquisition

spy_returns = pd.read_csv(”C:\\Users\\blazo\\Documents\\Misc\\QJ\\quant-journey\\data\\returns\\returns_SPY.csv”, index_col=0, parse_dates=True)

tlt_returns = pd.read_csv(”C:\\Users\\blazo\\Documents\\Misc\\QJ\\quant-journey\\data\\returns\\returns_TLT.csv”, index_col=0, parse_dates=True)

gld_returns = pd.read_csv(”C:\\Users\\blazo\\Documents\\Misc\\QJ\\quant-journey\\data\\returns\\returns_GLD.csv”, index_col=0, parse_dates=True)

# 2. Data Preparation

# Combine all returns into a single DataFrame

close_df = pd.DataFrame({

‘SPY’: spy_returns[’Close’],

‘TLT’: tlt_returns[’Close’],

‘GLD’: gld_returns[’Close’]

})

# Drop rows with any missing data

close_df = close_df.dropna()This block is the initial ingestion and alignment step for your time series inputs — the moment when raw source files become a single, clean panel you can use for portfolio construction, risk calculations, or backtests.

First, each CSV is read into a pandas object with the first column parsed as the datetime index. Using index_col=0 and parse_dates ensures the series are true time series (dtype datetime64) so downstream operations like resampling, rolling windows, alignment, or plotting behave correctly. Because you read one file per asset, each resulting object is keyed by date and contains whatever column structure is in the CSV; here the code pulls the ‘Close’ column from each file. Note: the filenames include “returns” which suggests these files may already contain return series, but the code selects a column named ‘Close’ — you should double-check whether those CSVs actually hold raw prices or returns. If they are prices, you must convert them to returns before any volatility/correlation calculations; if they are returns, treating them as a ‘Close’ series is fine but the naming is confusing and worth clarifying.

When the three asset series are combined into close_df via a dict, pandas aligns them by their datetime index. That alignment uses the union of all dates by default, so if one asset is missing a date (e.g., different listing dates, exchange holidays, or sparse data), the combined DataFrame will contain NaNs at those timestamps. The immediate dropna() removes any row that contains a missing value across any asset — turning that union-of-dates view into an intersection. This is deliberate: many quantitative computations (covariance matrices, standardized returns, rolling correlations, portfolio returns computed as a weighted sum) assume that observations are synchronous across assets. Keeping rows with missing values would either force you to impute (which can introduce bias or spurious signals) or to add special-case logic everywhere; dropping them here keeps the dataset clean and avoids subtle errors in downstream math.

Two practical implications to keep in mind for quant work: (1) dropping rows reduces sample length and can bias the dataset if one asset has materially different trading history — if that matters for your strategy you may prefer an explicit join strategy (e.g., pd.concat with join=’inner’ or controlled imputation). (2) confirm that the time ordering is correct and that there are no duplicate timestamps; many downstream algorithms assume strictly increasing, unique indices. Finally, consider making the file paths and the column you select configurable, and add an assertion or small sanity checks (like checking whether the values look like prices vs returns, and that the index is sorted) so you don’t accidentally feed raw prices into return-based logic later.

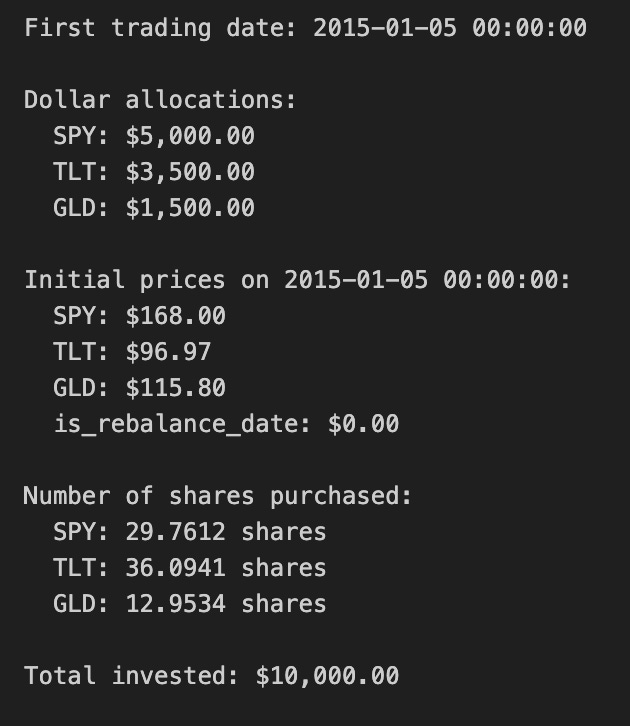

# 3. Portfolio Initialization

# Set initial capital and asset weights

initial_capital = 10000.00

weights = {

‘SPY’: 0.50,

‘TLT’: 0.35,

‘GLD’: 0.15

}

# Select the first trading date

first_date = close_df.index[0]

print(f”First trading date: {first_date}”)

# Calculate dollar allocation per asset

allocations = {

‘SPY’: initial_capital * weights[’SPY’],

‘TLT’: initial_capital * weights[’TLT’],

‘GLD’: initial_capital * weights[’GLD’]

}

print(f”\nDollar allocations:”)

for ticker, amount in allocations.items():

print(f” {ticker}: ${amount:,.2f}”)

# Get initial prices

initial_prices = close_df.loc[first_date]

print(f”\nInitial prices on {first_date}:”)

for ticker, price in initial_prices.items():

print(f” {ticker}: ${price:.2f}”)

# Determine the number of shares for each asset

shares = {

‘SPY’: allocations[’SPY’] / initial_prices[’SPY’],

‘TLT’: allocations[’TLT’] / initial_prices[’TLT’],

‘GLD’: allocations[’GLD’] / initial_prices[’GLD’]

}

print(f”\nNumber of shares purchased:”)

for ticker, num_shares in shares.items():

print(f” {ticker}: {num_shares:.4f} shares”)

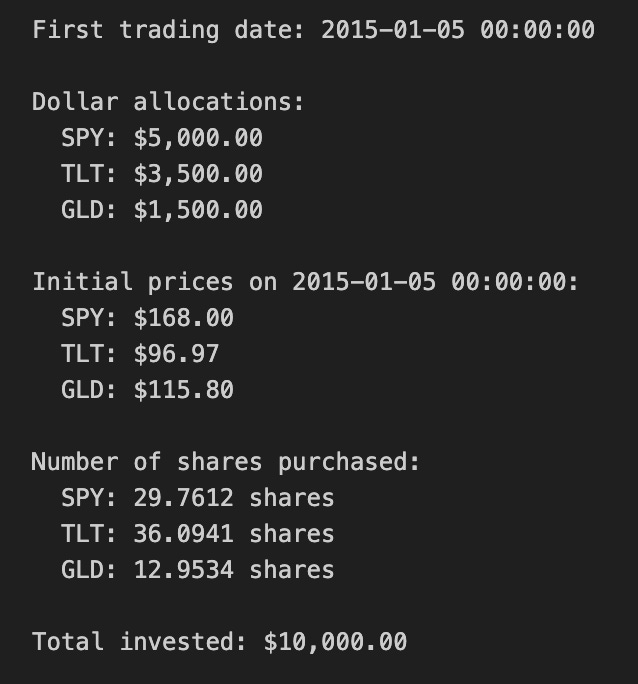

# Calculate actual invested amount (accounting for fractional shares)

total_invested = sum(shares[ticker] * initial_prices[ticker] for ticker in shares.keys())

print(f”\nTotal invested: ${total_invested:,.2f}”)This block initializes a simulated portfolio for a quant trading backtest by turning a target capital and percentage weights into concrete position sizes on the first available market date. It begins with a stated initial capital and a dictionary of target portfolio weights for three tickers; those weights express the intended risk or exposure mix (equities via SPY, long-duration bonds via TLT, and gold via GLD). Using the first timestamp from the price DataFrame (close_df.index[0]) establishes the consistent starting point for the strategy so all allocations are priced off the same snapshot; the code prints that date for transparency and reproducibility.

Next, the code converts percentage weights into dollar allocations by multiplying each weight by the initial capital. This step is fundamental: quant strategies operate on dollars (or shares), so the abstract weight vector must be mapped to monetary amounts to create tradable positions. The explicit allocations are printed so you can verify the capital partitioning before any orders are modeled or executed.

With dollar allocations known, the code pulls the actual close prices on the chosen start date from close_df. Using actual market prices is crucial because the number of shares you can buy depends on the market price at execution: weights alone don’t tell you how many shares to trade. The code prints these prices to provide visibility into the price basis used for sizing.

The share-sizing step divides each asset’s dollar allocation by its initial price to compute the number of shares to purchase. This approach assumes fractional shares are allowable (the result is a floating-point number). In a backtest that models fractional shares, this directly maps target exposure to precise notional positions and keeps the realized portfolio close to the intended weights. If you were modeling integer-share trading on an exchange that doesn’t support fractions, you’d need to floor/round shares and track any leftover cash; the code intentionally does not do that here.

Finally, total_invested recomputes the actual dollars deployed by summing shares times their prices. In an ideal fractional-share scenario this equals the initial capital (up to floating-point precision), but the explicit recomputation is a useful sanity check to surface NaNs, price mismatches, or weight-sum errors early. The prints let you confirm no capital was inadvertently left unused or oversubscribed.

Practical caveats for quant trading: this snippet assumes the weight vector sums to 1 and that close_df has valid, non-NaN prices on the first date — both should be validated upstream. It also omits transaction costs, spreads, execution slippage, and market impact, which in live trading can meaningfully change realized exposure; incorporate those in later order-execution modeling. Lastly, if you plan to rebalance, track cash leftover from integer-share constraints or explicitly model fractional-share execution and any rounding policy at each rebalance to keep simulated P&L realistic.

# 4. Equity Curve Construction

# Calculate daily equity for each asset

equity_df = pd.DataFrame(index=close_df.index)

for ticker in [’SPY’, ‘TLT’, ‘GLD’]:

equity_df[f’{ticker}_equity’] = shares[ticker] * close_df[ticker]

# Compute total portfolio equity

equity_df[’total_equity’] = equity_df[’SPY_equity’] + equity_df[’TLT_equity’] + equity_df[’GLD_equity’]

# 5. Returns Calculation

# Compute portfolio daily returns

returns_df = pd.DataFrame(index=close_df.index)

returns_df[’portfolio_return’] = equity_df[’total_equity’].pct_change()

# Compute individual asset daily returns

returns_df[’SPY_return’] = equity_df[’SPY_equity’].pct_change()

returns_df[’TLT_return’] = equity_df[’TLT_equity’].pct_change()

returns_df[’GLD_return’] = equity_df[’GLD_equity’].pct_change()

# Drop the first row (NaN due to pct_change)

returns_df = returns_df.dropna()

# 6. Performance Statistics

# Assume 252 trading days per year

trading_days = 252

# Calculate annualized return

total_return = (equity_df[’total_equity’].iloc[-1] / equity_df[’total_equity’].iloc[0]) - 1

num_years = len(returns_df) / trading_days

annualized_return = (1 + total_return) ** (1 / num_years) - 1

# Calculate annualized volatility

annualized_volatility = returns_df[’portfolio_return’].std() * np.sqrt(trading_days)

# Calculate Sharpe ratio (assuming 0% risk-free rate)

risk_free_rate = 0.0

sharpe_ratio = (annualized_return - risk_free_rate) / annualized_volatility

# Calculate maximum drawdown

cumulative_returns = (1 + returns_df[’portfolio_return’]).cumprod()

running_max = cumulative_returns.cummax()

drawdown = (cumulative_returns - running_max) / running_max

max_drawdown = drawdown.min()

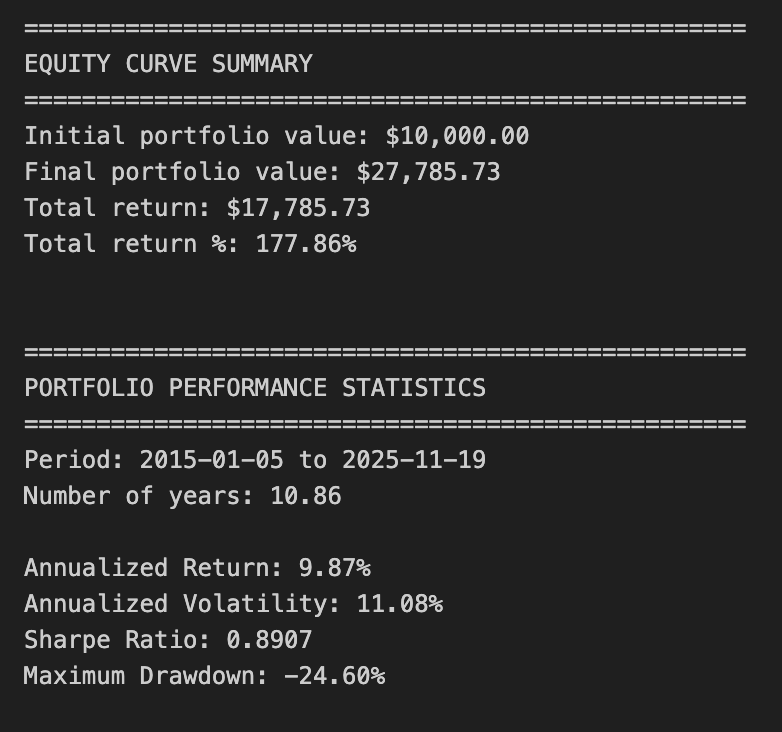

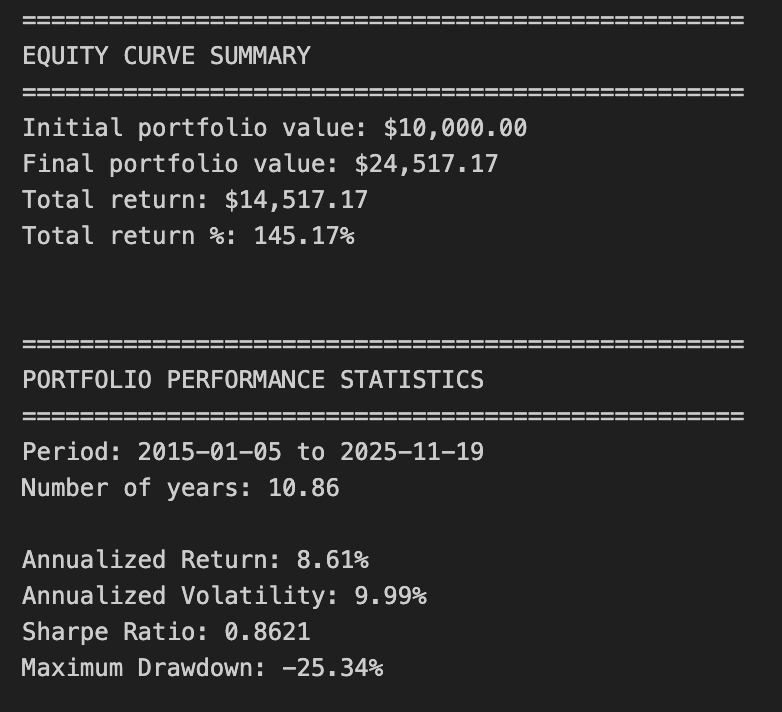

# Display equity curve summary

print(”=” * 50)

print(”EQUITY CURVE SUMMARY”)

print(”=” * 50)

print(f”Initial portfolio value: ${equity_df[’total_equity’].iloc[0]:,.2f}”)

print(f”Final portfolio value: ${equity_df[’total_equity’].iloc[-1]:,.2f}”)

print(f”Total return: ${equity_df[’total_equity’].iloc[-1] - equity_df[’total_equity’].iloc[0]:,.2f}”)

print(f”Total return %: {((equity_df[’total_equity’].iloc[-1] / equity_df[’total_equity’].iloc[0]) - 1) * 100:.2f}%”)

print(”\n”)

# Display results

print(”=” * 50)

print(”PORTFOLIO PERFORMANCE STATISTICS”)

print(”=” * 50)

print(f”Period: {equity_df.index[0].strftime(’%Y-%m-%d’)} to {equity_df.index[-1].strftime(’%Y-%m-%d’)}”)

print(f”Number of years: {num_years:.2f}”)

print(f”\nAnnualized Return: {annualized_return:.2%}”)

print(f”Annualized Volatility: {annualized_volatility:.2%}”)

print(f”Sharpe Ratio: {sharpe_ratio:.4f}”)

print(f”Maximum Drawdown: {max_drawdown:.2%}”)This block constructs a simple equity curve for a three-asset portfolio, derives daily returns from that curve, and computes standard performance metrics used in quantitative trading to summarize risk and return. The overall goal is to translate per-asset positions into a time series of portfolio value, then convert that into annualized return, volatility, Sharpe ratio and maximum drawdown so you can judge whether the allocation/strategy meets your objectives.

First, the code builds equity_df by taking the current close price for each asset and multiplying by shares[ticker]. That produces a per-asset dollar-value time series (e.g., SPY_equity = shares[‘SPY’] * SPY_price). Implicit in this step is the assumption that shares[…] are fixed quantities through time (no rebalancing or partial execution adjustments). This is important: the equity curve reflects price movement only; if you expect dynamic position sizing or intraperiod trades, you’d need to update shares over time or compute P&L differently.

Next it sums the three per-asset series into total_equity. That total is the portfolio-level mark-to-market at each timestamp and is the primary series used for portfolio returns and most metrics. Converting to returns is done with .pct_change(): portfolio_return = total_equity.pct_change() and the same for each asset. pct_change computes the period-over-period relative change (d_t = V_t/V_{t-1} — 1), which is the right measure when positions are constant and you want simple daily returns. The first row is NaN because there is no prior period to compare to, so the code drops that row with dropna() to keep the subsequent statistics clean.

For performance statistics the code follows standard quant practice: compute total_return as the simple cumulative return across the whole sample (final / initial — 1), then convert that to an annualized return using a geometric (compound) formula. It derives num_years as len(returns_df)/252 assuming 252 trading days per year, then computes annualized_return = (1 + total_return) ** (1 / num_years) — 1. Using the geometric mean (instead of arithmetic average) properly accounts for compounding across the sample period, which is what you want for multi-period portfolio performance.

Volatility is annualized by taking the standard deviation of daily portfolio returns and scaling by sqrt(trading_days). That reflects the usual conversion from daily to annualized volatility under the Brownian-motion-like scaling assumption. Note a subtlety: pandas Series.std() uses ddof=1 (sample standard deviation) by default; that’s common but something to be aware of if you want population volatility (ddof=0) for very short samples. The Sharpe ratio is then computed as (annualized_return — risk_free_rate) / annualized_volatility using risk_free_rate = 0.0 in this code. Setting the risk-free rate to zero is a simplification — in live performance reporting you should use an appropriate short-term rate to avoid overstating real excess return.

Maximum drawdown is calculated from the cumulative return path: cumulative_returns = (1 + daily_returns).cumprod() gives a running wealth index, running_max = cumulative_returns.cummax() gives the historical highs, and drawdown = (cumulative_returns — running_max) / running_max gives the percentage decline from peak at every point. Taking drawdown.min() yields the worst (most negative) drawdown. This approach correctly measures peak-to-trough losses, which is critical for risk assessment in quant strategies because it captures path dependency that volatility alone misses.

Finally, the code prints a concise summary of initial vs final portfolio value, total dollar and percentage return, the period and number of years, and the key metrics. A few practical caveats to bear in mind: because shares are treated as constant, this performance reflects a buy-and-hold weighting — if your strategy rebalances or changes exposures you must recompute positions over time; num_years derived from a fixed 252 trading days may be slightly imprecise for irregular calendars or missing dates (using actual date differences can be more accurate); and division-by-zero or extremely low volatility can make Sharpe unstable. Also consider using a non-zero risk-free rate, handling fees/transaction costs, and ensuring returns are computed on the same calendar (business days) as your price series when moving from backtest to production reporting.

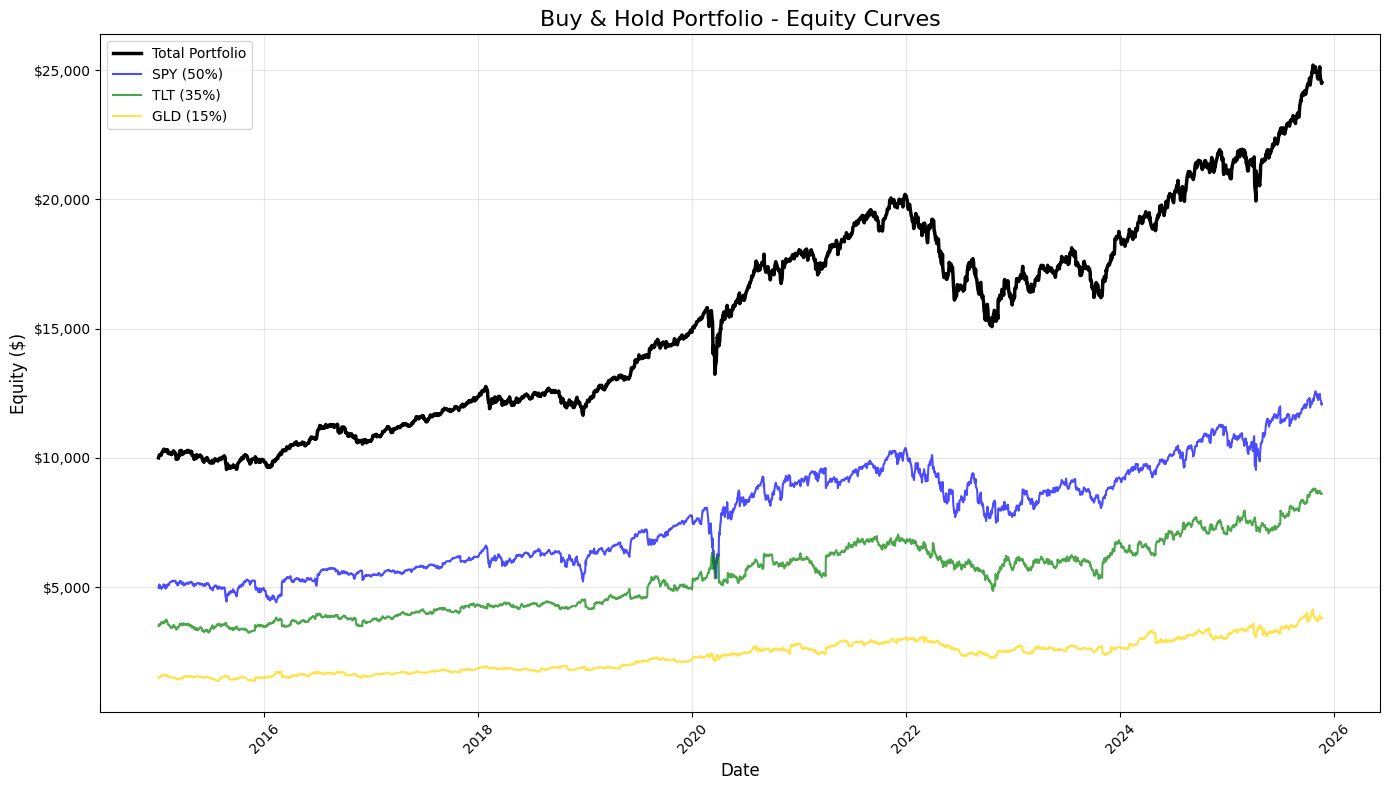

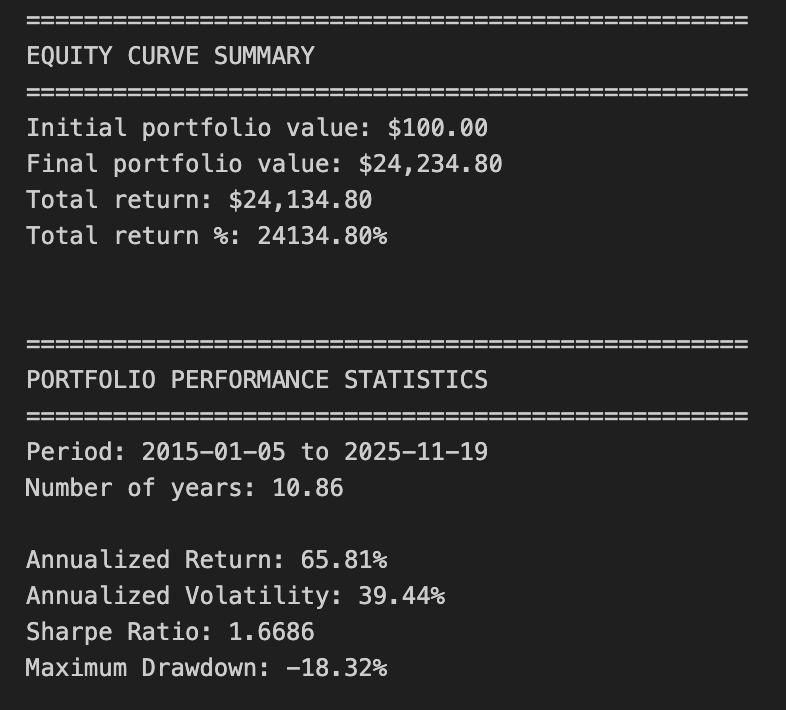

# 7. Static Visualizations

# Create figure and axis

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(14, 8))

# Plot equity curves

ax.plot(equity_df.index, equity_df[’total_equity’], label=’Total Portfolio’, linewidth=2.5, color=’black’)

ax.plot(equity_df.index, equity_df[’SPY_equity’], label=’SPY (50%)’, linewidth=1.5, alpha=0.7, color=’blue’)

ax.plot(equity_df.index, equity_df[’TLT_equity’], label=’TLT (35%)’, linewidth=1.5, alpha=0.7, color=’green’)

ax.plot(equity_df.index, equity_df[’GLD_equity’], label=’GLD (15%)’, linewidth=1.5, alpha=0.7, color=’gold’)

# Formatting

ax.set_title(’Buy & Hold Portfolio - Equity Curves’, fontsize=16)

ax.set_xlabel(’Date’, fontsize=12)

ax.set_ylabel(’Equity ($)’, fontsize=12)

ax.legend(loc=’best’, fontsize=10)

ax.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# Format y-axis as currency

ax.yaxis.set_major_formatter(plt.FuncFormatter(lambda x, p: f’${x:,.0f}’))

# Rotate x-axis labels

plt.xticks(rotation=45)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()This block produces a static, publication-quality chart that contrasts the total portfolio equity against the three underlying buy-and-hold components over time. It consumes equity_df — a time-indexed DataFrame whose columns represent cumulative dollar equity for the blended portfolio and for each asset (SPY, TLT, GLD) given their target allocations. Chronologically, the code first creates a plotting canvas sized for legibility, then draws four time series: the consolidated portfolio (“total_equity”) and each asset-specific equity curve. Plotting the total portfolio alongside the components makes the relationship between allocation and aggregate performance explicit: you can see when one asset’s gains or losses dominate the portfolio and how diversification smooths or amplifies moves.

Styling choices carry informational intent. The total portfolio is drawn thicker and in black to visually prioritize it as the primary metric of interest, while the component curves are thinner, semi-transparent, and colored to remain visible but secondary. The labels include the target weights (50% SPY, 35% TLT, 15% GLD) so viewers immediately understand that these traces are not raw index values but position-level equity given those allocations. Using alpha transparency on the component traces reduces visual clutter where lines overlap, and distinct colors help track each asset through different market regimes.

Formatting is deliberate to improve interpretability for trading analysis. A descriptive title and axis labels orient the viewer to timeframe and monetary scale. The legend is placed automatically to minimize overlap with data, and a subtle grid enhances the ability to read relative moves and turning points without dominating the chart. The y-axis is formatted as currency — converting raw numeric ticks into dollar-formatted labels — because investment performance is more actionable and intuitive when expressed in dollars rather than raw numbers or percentages for this style of equity-curve presentation. Rotating x-axis labels and applying tight_layout prevent tick labels and other annotations from being clipped, which is important when dates are dense over long backtests.

From a quant-trading perspective, this visualization is an early diagnostic tool: it shows realized dollar P&L paths, highlights periods where one asset drives portfolio returns, and helps surface regime shifts, drawdowns, and the effectiveness of the static allocation. When you inspect these curves, you’re looking for divergence between the portfolio and its components (indicating concentration or hedging effects), persistent under- or out-performance relative to the major component, and visually-identifiable drawdown recoveries. Finally, plt.show() renders the figure for review; for iterative analysis you might keep this as a static snapshot for reporting, or extend it with overlays (drawdown shading, rolling volatility) or interactive tools for deeper investigation.

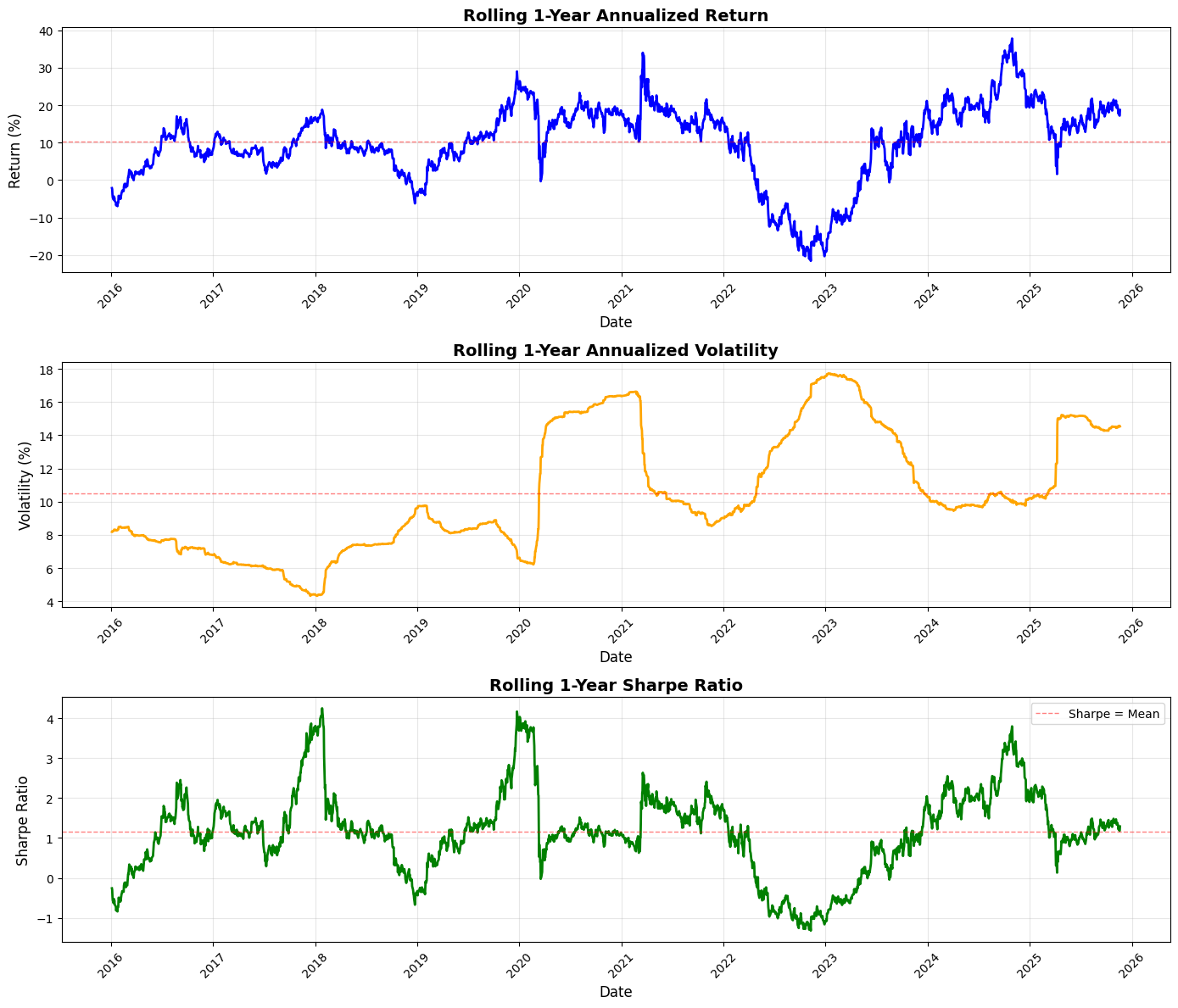

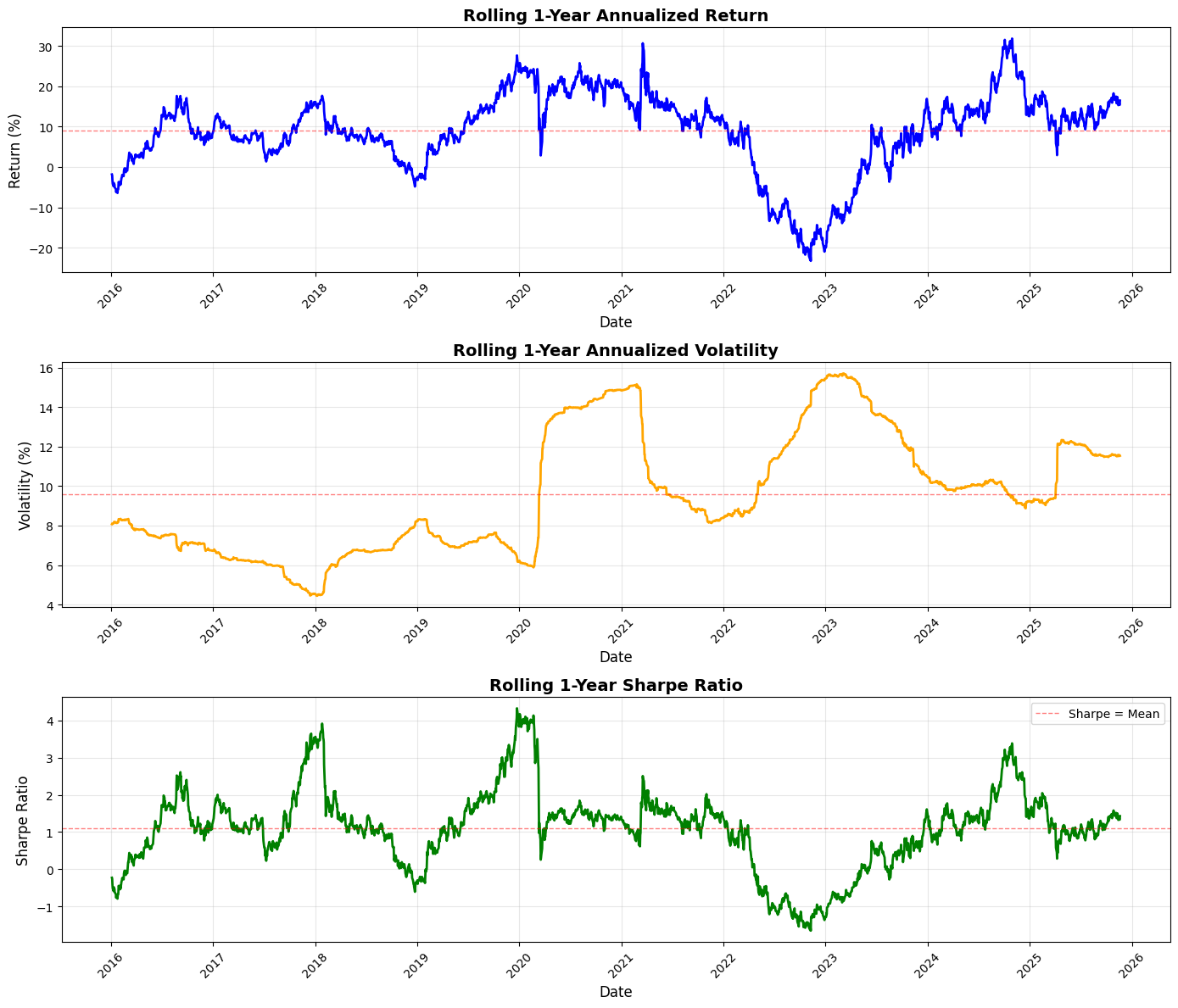

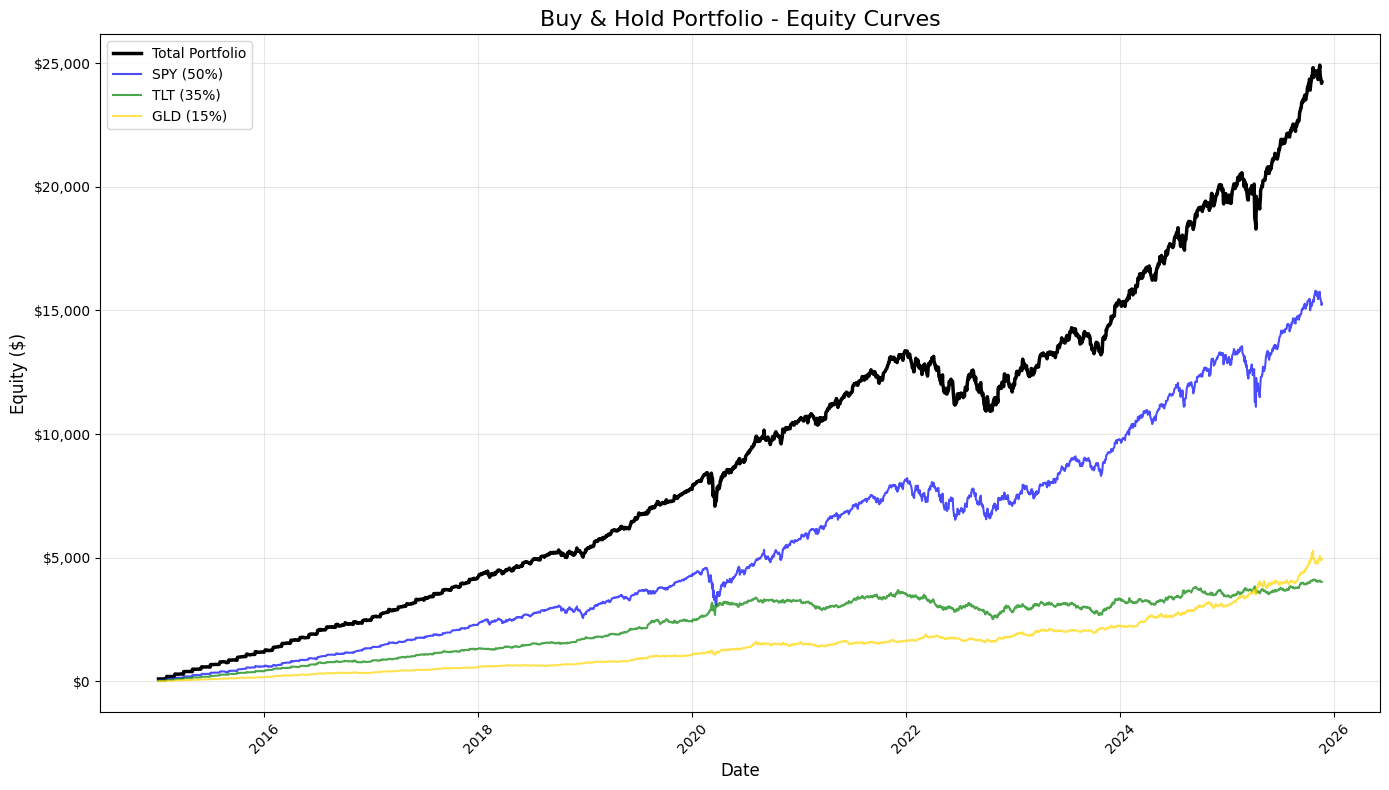

# 8. Rolling Performance Analysis

# Define rolling window (252 trading days = 1 year)

window = 252

# Calculate rolling metrics

rolling_return = returns_df[’portfolio_return’].rolling(window=window).apply(

lambda x: (1 + x).prod() ** (252 / len(x)) - 1

)

rolling_volatility = returns_df[’portfolio_return’].rolling(window=window).std() * np.sqrt(252)

rolling_sharpe = rolling_return / rolling_volatility

# Create subplots

fig, axes = plt.subplots(3, 1, figsize=(14, 12))

# 1. Rolling 1-Year Annualized Return

axes[0].plot(rolling_return.index, rolling_return * 100, linewidth=2, color=’blue’)

axes[0].axhline(y=rolling_return.mean() * 100, color=’red’, linestyle=’--’, linewidth=1, alpha=0.5, label=’Return = Mean’)

axes[0].set_title(’Rolling 1-Year Annualized Return’, fontsize=14, fontweight=’bold’)

axes[0].set_ylabel(’Return (%)’, fontsize=12)

axes[0].grid(True, alpha=0.3)

axes[0].set_xlabel(’Date’, fontsize=12)

# 2. Rolling 1-Year Annualized Volatility

axes[1].plot(rolling_volatility.index, rolling_volatility * 100, linewidth=2, color=’orange’)

axes[1].axhline(y=rolling_volatility.mean() * 100, color=’red’, linestyle=’--’, linewidth=1, alpha=0.5, label=’Volatility = Mean’)

axes[1].set_title(’Rolling 1-Year Annualized Volatility’, fontsize=14, fontweight=’bold’)

axes[1].set_ylabel(’Volatility (%)’, fontsize=12)

axes[1].grid(True, alpha=0.3)

axes[1].set_xlabel(’Date’, fontsize=12)

# 3. Rolling 1-Year Sharpe Ratio

axes[2].plot(rolling_sharpe.index, rolling_sharpe, linewidth=2, color=’green’)

axes[2].axhline(y=rolling_sharpe.mean(), color=’red’, linestyle=’--’, linewidth=1, alpha=0.5, label=’Sharpe = Mean’)

axes[2].set_title(’Rolling 1-Year Sharpe Ratio’, fontsize=14, fontweight=’bold’)

axes[2].set_ylabel(’Sharpe Ratio’, fontsize=12)

axes[2].grid(True, alpha=0.3)

axes[2].set_xlabel(’Date’, fontsize=12)

axes[2].legend(loc=’best’, fontsize=10)

# Format x-axis for all subplots

for ax in axes:

ax.tick_params(axis=’x’, rotation=45)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

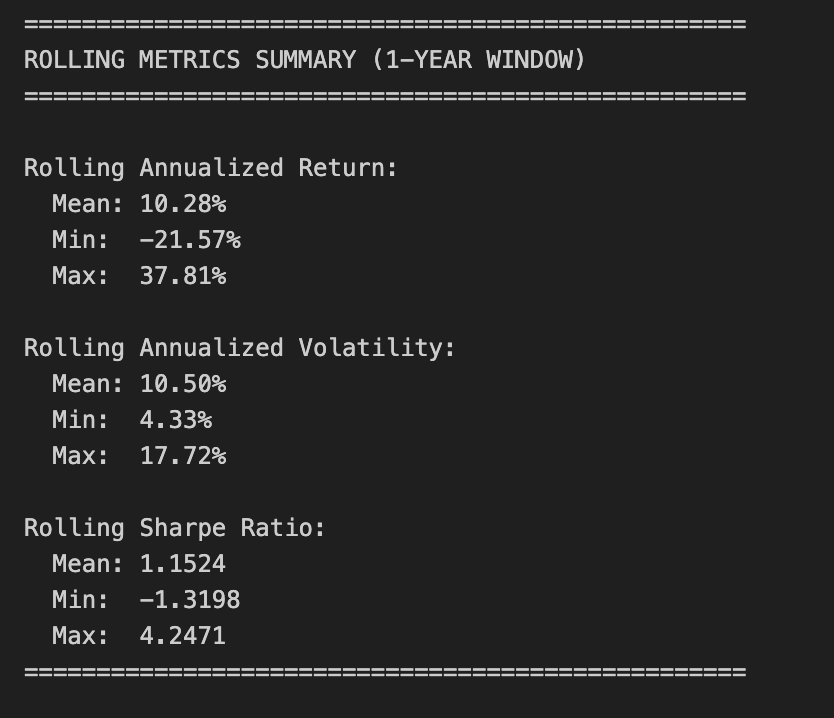

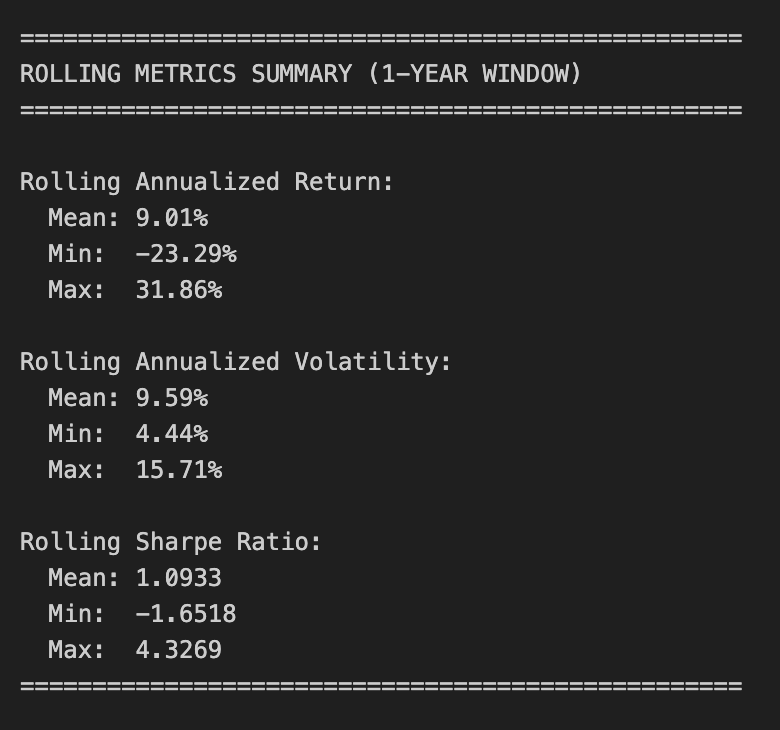

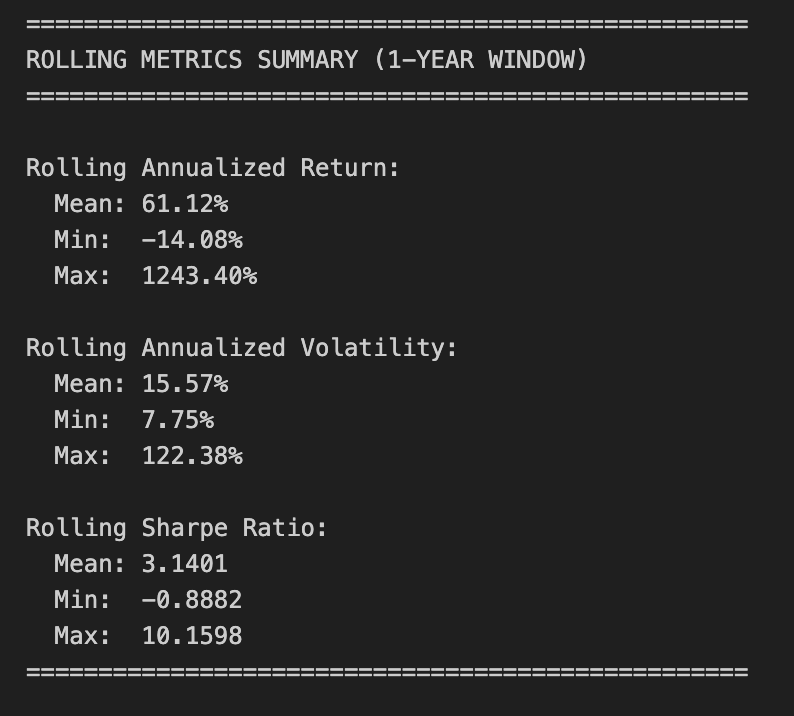

# Print summary statistics for rolling metrics

print(”\n” + “=” * 50)

print(”ROLLING METRICS SUMMARY (1-YEAR WINDOW)”)

print(”=” * 50)

print(”\nRolling Annualized Return:”)

print(f” Mean: {rolling_return.mean():.2%}”)

print(f” Min: {rolling_return.min():.2%}”)

print(f” Max: {rolling_return.max():.2%}”)

print(”\nRolling Annualized Volatility:”)

print(f” Mean: {rolling_volatility.mean():.2%}”)

print(f” Min: {rolling_volatility.min():.2%}”)

print(f” Max: {rolling_volatility.max():.2%}”)

print(”\nRolling Sharpe Ratio:”)

print(f” Mean: {rolling_sharpe.mean():.4f}”)

print(f” Min: {rolling_sharpe.min():.4f}”)

print(f” Max: {rolling_sharpe.max():.4f}”)

print(”=” * 50)This block performs a standard rolling (time-windowed) performance analysis of a portfolio so you can see how annualized return, volatility, and risk‑adjusted return (Sharpe) evolve through time — a common monitoring and diagnostic tool in quant trading to detect regime changes, strategy deterioration, or risk concentration.

We start by defining the lookback window as 252 trading days (one nominal trading year). For rolling annualized return, the code takes the series of simple daily portfolio returns and, within each 252-day window, computes the compounded growth factor via (1 + r).prod(). That product gives the cumulative gross return over the window; raising it to the power (252 / len(x)) annualizes that multi-day return to a 1‑year equivalent and subtracting 1 converts back to a net annualized return. Using the product of (1 + r) preserves compounding (important for realistic performance comparison across windows) and the exponent rescales the realized holding-period return to an annual basis so values at different dates are comparable.

Volatility is computed as the rolling sample standard deviation of daily returns in the same window, then scaled by sqrt(252) to annualize. This follows the Brownian-motion style scaling commonly used in practice — it gives you an annualized dispersion measure that’s directly comparable to the annualized return above. The rolling Sharpe ratio is simply the pointwise ratio of the two series (annualized return divided by annualized volatility). Note this implementation assumes a zero risk‑free rate and that volatility is nonzero; in production you’ll likely want to subtract a rolling/constant risk‑free rate and guard against division by (near) zero volatility.

Next the code visualizes those three rolling series in vertically stacked subplots: annualized return, annualized volatility, and Sharpe. For return and volatility the plots scale to percent for readability (multiplying by 100), and each panel draws a dashed horizontal line at the series mean to provide a simple benchmark. Plot styling (line widths, colors, grid, titles, labels) is there to make trends, regime shifts, and excursions above/below long-run averages easy to spot. The code rotates x‑ticks and uses tight_layout to keep date labels legible and avoid overlap.

Finally, the script prints a compact summary of the rolling statistics (mean, min, max) for each metric so you get quick numeric checkpoints alongside the visual diagnostics. A few practical caveats to keep in mind: pandas.rolling with window=252 produces NaNs for the first 251 rows unless min_periods is changed, and the lambda uses len(x) so partial-window annualization only happens if you explicitly allow fewer than 252 observations; pandas.Series.std defaults to sample std (ddof=1), which may or may not be what you expect; and the Sharpe here ignores a risk‑free rate and can be unstable if volatility is very low. Also consider whether simple returns are the right primitive (vs. log returns) for your downstream analysis, and remember to watch for typical quant pitfalls such as look‑ahead bias, survivor bias, and non‑synchronous data when interpreting rolling behavior.

Risk-Premia Harvesting — Buy-and-Hold Strategy with Monthly Rebalancing

Overview

This notebook implements a buy-and-hold strategy with monthly rebalancing to harvest risk premia from a diversified portfolio. Rather than remaining unadjusted, the portfolio is rebalanced to target weights at each month end to maintain consistent risk exposure over the investment horizon (approximately 10 years).

Portfolio composition:

SPY (S&P 500 ETF): 50%

TLT (Long-term Treasury ETF): 35%

GLD (Gold ETF): 15%

Initial capital: $10,000.00

Rebalancing frequency: Monthly (end of month)

Target Outputs

Performance metrics

Annualized return

Annualized volatility

Sharpe ratio

Maximum drawdown

Visualizations

Equity curves (total portfolio and individual assets)

1-year rolling annualized return

1-year rolling annualized volatility

1-year rolling Sharpe ratio

Implementation steps

1. Data acquisition

Load historical price data for SPY, TLT, and GLD.

2. Data preparation

Remove rows with missing data.

Align all tickers to the same date index.

Identify month-end dates for rebalancing.

3. Portfolio initialization

Set the initial capital and target asset weights.

Choose the initial trading date.

Calculate dollar allocation per asset using the target weights.

Determine the number of shares for each asset.

4. Equity curve construction with monthly rebalancing

Calculate daily equity for each asset based on current holdings.

Compute total portfolio equity daily.

At each month end:

Calculate the current portfolio value.

Rebalance by adjusting share quantities to restore target weights.

Update holdings for the next period.

Consolidate results into a single DataFrame.

5. Returns calculation

Compute portfolio daily returns.

Compute individual asset daily returns.

6. Performance statistics

Calculate annualized return.

Calculate annualized volatility.

Calculate the Sharpe ratio.

Calculate maximum drawdown.

7. Static visualizations

Plot all equity curves on a single chart.

8. Rolling performance analysis

Generate a 1-year rolling annualized return chart.

Generate a 1-year rolling annualized volatility chart.

Generate a 1-year rolling Sharpe ratio chart.

# Imports

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# 1. Data Acquisition

spy_returns = pd.read_csv(”C:\\Users\\blazo\\Documents\\Misc\\QJ\\quant-journey\\data\\returns\\returns_SPY.csv”, index_col=0, parse_dates=True)

tlt_returns = pd.read_csv(”C:\\Users\\blazo\\Documents\\Misc\\QJ\\quant-journey\\data\\returns\\returns_TLT.csv”, index_col=0, parse_dates=True)

gld_returns = pd.read_csv(”C:\\Users\\blazo\\Documents\\Misc\\QJ\\quant-journey\\data\\returns\\returns_GLD.csv”, index_col=0, parse_dates=True)

# 2. Data Preparation

# Combine all returns into a single DataFrame

close_df = pd.DataFrame({

‘SPY’: spy_returns[’Close’],

‘TLT’: tlt_returns[’Close’],

‘GLD’: gld_returns[’Close’]

})

# Drop rows with any missing data

close_df = close_df.dropna()

# Identify month-end dates for rebalancing

month_end_dates = close_df.resample(’ME’).last().index

# Create a boolean column to mark rebalancing dates

close_df[’is_rebalance_date’] = close_df.index.isin(month_end_dates)This block performs the initial data ingestion and alignment you need before any portfolio logic or backtest runs, and it explicitly sets up the monthly rebalancing signal you’ll use for the strategy. First, three CSV files are read into time-indexed pandas Series/DataFrames with parse_dates so the index is a DatetimeIndex; this is important because all subsequent resampling and calendar-aware operations depend on a proper date index. The code then constructs a single DataFrame (close_df) that pulls the ‘Close’ column from each source into parallel columns named by ticker. Whether those CSVs hold prices or precomputed returns, treating them as aligned series under the same index is the goal: downstream code will compute portfolio-level metrics and make trading decisions assuming each row represents the same trading timestamp across all assets.

Next, close_df = close_df.dropna() enforces that every row used in the backtest contains data for all three assets. This is a deliberate choice to avoid partial observations that would otherwise produce misleading portfolio weights, erroneous return calculations, or hidden look-ahead/forward-fill artifacts. It reduces the usable sample to the intersection of the three asset calendars, which is usually what you want for clean portfolio calculations; if you need to preserve data when one asset is missing you would instead handle NaNs explicitly (forward-fill, imputation, or hybrid logic), but that would introduce its own assumptions.

To implement monthly rebalancing, the code resamples the cleaned series with .resample(‘ME’).last() — resampling at ‘ME’ (month end) and then taking the last available observation in each month returns the last trading-day timestamp of each calendar month, not the calendar date itself if markets were closed. That choice ensures rebalances occur on the last available market day for each month (which is the usual practical convention for monthly rebalance schedules). Finally, close_df[‘is_rebalance_date’] = close_df.index.isin(month_end_dates) marks those rows with a boolean flag so later logic can trigger weight updates or trade execution only on flagged dates. Using .isin on the existing index is robust because month_end_dates were derived from the same index, so the flag will be True exactly on the last trading-day rows and False elsewhere.

Put together, this block synchronizes the asset histories, removes incomplete observations to avoid subtle calculation bugs, and creates an explicit, reproducible monthly rebalancing signal that downstream portfolio logic will use to decide when to adjust positions. A couple of practical checks to keep in mind: confirm that the CSV ‘Close’ column really contains the data type you expect (price vs. return), and be aware that dropna reduces sample size if asset calendars differ — if that’s undesirable, handle missing data explicitly before computing portfolio returns.

# 3. Portfolio Initialization

# Set initial capital and asset weights

initial_capital = 10000.00

weights = {

‘SPY’: 0.50,

‘TLT’: 0.35,

‘GLD’: 0.15

}

# Select the first trading date

first_date = close_df.index[0]

print(f”First trading date: {first_date}”)

# Calculate dollar allocation per asset

allocations = {

‘SPY’: initial_capital * weights[’SPY’],

‘TLT’: initial_capital * weights[’TLT’],

‘GLD’: initial_capital * weights[’GLD’]

}

print(f”\nDollar allocations:”)

for ticker, amount in allocations.items():

print(f” {ticker}: ${amount:,.2f}”)

# Get initial prices

initial_prices = close_df.loc[first_date]

print(f”\nInitial prices on {first_date}:”)

for ticker, price in initial_prices.items():

print(f” {ticker}: ${price:.2f}”)

# Determine the number of shares for each asset

shares = {

‘SPY’: allocations[’SPY’] / initial_prices[’SPY’],

‘TLT’: allocations[’TLT’] / initial_prices[’TLT’],

‘GLD’: allocations[’GLD’] / initial_prices[’GLD’]

}

print(f”\nNumber of shares purchased:”)

for ticker, num_shares in shares.items():

print(f” {ticker}: {num_shares:.4f} shares”)

# Calculate actual invested amount (accounting for fractional shares)

total_invested = sum(shares[ticker] * initial_prices[ticker] for ticker in shares.keys())

print(f”\nTotal invested: ${total_invested:,.2f}”)This block establishes the starting portfolio for the backtest: it converts a set of target asset weights into actual positions measured in shares, using the first available close prices and a fixed initial capital. We begin by expressing the investment intention in two places: initial_capital (the cash we will deploy) and weights (the percentage of that capital allocated to each ticker). Using percentages keeps the strategy scale-independent and specifies the desired exposure mix — here 50% equity (SPY), 35% long-duration bonds (TLT), and 15% gold (GLD). Implicitly this assumes the weights sum to 1.0 so the entire capital is intended to be invested across these assets.

The code then selects first_date as the earliest timestamp in close_df. This is the deterministic anchor for portfolio construction: we use the market prices on that date to turn dollar allocations into tradable quantities. It’s important that this index row is valid (no NaNs, and represents a real trading close); otherwise the subsequent arithmetic will be wrong or raise errors. Printing first_date is purely diagnostic to confirm the starting point of the simulation.

Next, allocations are computed by multiplying initial_capital by each asset’s weight. This converts the abstract weight vector into concrete dollar amounts to spend on each asset. Converting to dollars at the outset is necessary because market prices are denominated in currency, and share counts must be derived from dollars divided by price.

The code reads initial_prices from close_df.loc[first_date], which gives the closing price per share for each ticker on the start date. Dividing the dollar allocation by these prices yields shares for each asset. In this implementation shares are floating-point (fractional) numbers; that choice simplifies backtesting math and ensures the capital is fully invested according to the intended weights. The trade-off is that fractional-share execution ignores real-world constraints such as minimum lot sizes, integer-share rounding, transaction costs, and market impact.

Finally, total_invested recomputes the portfolio value by summing price * shares across tickers. This acts as a sanity check: with fractional shares and no rounding/fees, total_invested should equal initial_capital (subject to floating-point precision). Calculating and printing total_invested lets you quickly verify that the conversion from weights -> dollars -> shares behaved as intended and shows if any cash remains uninvested. Throughout, the code assumes immediate execution at close prices and no trading frictions; for production-grade backtests you would want to add checks for missing prices, enforce integer-share rounding or simulate order fills, and account for commissions/slippage before deciding the final executed shares.

# 4. Equity Curve Construction with Monthly Rebalancing

# Initialize tracking dictionaries

current_shares = shares.copy()

equity_data = []

# Iterate through each date

for date in close_df.index:

# Get current prices

current_prices = close_df.loc[date, [’SPY’, ‘TLT’, ‘GLD’]]

# Calculate daily equity for each asset based on current holdings

spy_equity = current_shares[’SPY’] * current_prices[’SPY’]

tlt_equity = current_shares[’TLT’] * current_prices[’TLT’]

gld_equity = current_shares[’GLD’] * current_prices[’GLD’]

# Compute total portfolio equity daily

total_equity = spy_equity + tlt_equity + gld_equity

# Store the equity values

equity_data.append({

‘Date’: date,

‘SPY_equity’: spy_equity,

‘TLT_equity’: tlt_equity,

‘GLD_equity’: gld_equity,

‘total_equity’: total_equity

})

# At each month-end: rebalance

if close_df.loc[date, ‘is_rebalance_date’]:

# Calculate current portfolio value

portfolio_value = total_equity

# Rebalance: adjust share quantities to match target weights

current_shares[’SPY’] = (portfolio_value * weights[’SPY’]) / current_prices[’SPY’]

current_shares[’TLT’] = (portfolio_value * weights[’TLT’]) / current_prices[’TLT’]

current_shares[’GLD’] = (portfolio_value * weights[’GLD’]) / current_prices[’GLD’]

# Consolidate results into a unified DataFrame