Quant Trading Unlocked: From Crisis-Alpha Hedging to Algorithmic Backtesting

A practical guide to analyzing the ETF universe and validating strategies with data-driven simulations.

Use the button at the end of this article to download the source code.

This project provides a comprehensive toolkit for analyzing Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs), discovering hedging strategies, and backtesting algorithmic trading models. It aims to bridge the gap between exploratory data analysis and rigorous strategy evaluation, allowing users to move from market intuition to verifiable performance metrics.

Functionality

1. Market Exploration & Analysis

The framework begins by exploring the vast universe of ETFs. It performs statistical analysis to understand key asset characteristics such as:

Distribution of Assets: Breaking down the market by sector, region, and asset class.

Cost & Yield Analysis: Evaluating expense ratios and dividend yields to identify efficient investment vehicles.

Liquidity & Size: Analyzing market capitalization and volume to ensure strategies can be executed efficiently.

2. Strategic Hedging (Crisis Alpha)

A core component of the project is identifying assets that perform well when the broader market fails.

Correlation Analysis: It analyzes historical data, specifically during market crashes (like the 2008 financial crisis), to find Bond ETFs that exhibit strong inverse correlation to major equity indices (like the S&P 500).

Flight-to-Safety: By isolating these “safe haven” assets, the project helps construct portfolios that are resilient to market shocks.

3. Strategy Backtesting & Simulation

The project supports two primary approaches to portfolio management:

Passive “Lazy” Portfolios:

Simulates classic diversification strategies (e.g., the Swensen Portfolio) that rely on fixed asset allocation and periodic rebalancing.

These are benchmarked against standard market indices to evaluate the benefits of simple diversification.

Active “Online” Portfolio Selection (OLPS):

Evaluates advanced machine learning algorithms that adaptively reallocate portfolio weights based on recent price trends.

Algorithms like Universal Portfolios, Exponential Gradient, and Mean Reversion are tested to see if they can consistently outperform the market without identifying specific “winning” stocks.

Methodology: How It Works

The workflow typically follows these steps:

Data Ingestion: The system fetches historical financial data (adjusted closing prices) from online providers for a defined set of tickers.

Preprocessing: Raw data is cleaned, aligned on a common timeline, and checked for missing values to ensure simulation accuracy.

Simulation Loop:

Initialization: The strategy defines its universe of assets and trading logic (e.g., “rebalance every month” or “optimize weights daily”).

Execution: An event-driven backtester steps through historical time, processing daily or minute-level data. It handles order generation, transaction costs, and portfolio tracking.

Analysis & Visualization:

The system calculates performance metrics: Sharpe Ratio (risk-adjusted return), Drawdowns (risk of loss), and Alpha/Beta (market relativity).

It generates visualizations comparing the strategy’s cumulative returns against a benchmark, making it easy to identify outperformance.

How to Run

Prerequisites: Ensure you have a Python environment set up with the necessary financial data science libraries (Pandas, Matplotlib, etc.) and a compatible backtesting engine (like Zipline or a dedicated OLPS library).

Execution: The system is designed to be interactive. You typically run the analysis in sequential stages:

Step 1: Run the exploratory analysis to understand the data and select your asset universe.

Step 2: Execute the hedging analysis to select defensive assets.

Step 3: Run the backtest simulations for your chosen strategies (Passive or Active).

Interpreting Results: Review the generated plots and statistical tables to determine if a strategy meets your risk/return requirements before considering live deployment.

This document compares state-of-the-art Online Portfolio Selection (OLPS) algorithms to evaluate whether they can improve a rebalanced passive strategy in practice. The survey “Online Portfolio Selection: A Survey” by Bin Li and Steven C. H. Hoi provides a comprehensive review of multi-period portfolio allocation algorithms. The same authors developed the OLPS Toolbox, but for this work we use Mojmir Vinkler’s implementation and extend his comparison to a more recent timeline using a set of ETFs to avoid survivorship bias (as suggested by Ernie Chan) and reduce idiosyncratic risk.

Vinkler’s thesis performs much of the groundwork and concludes that Universal Portfolios perform similarly to Constant Rebalanced Portfolios and tend to work better for an uncorrelated set of small, volatile stocks. Here, the goal is to determine whether any OLPS strategy is applicable to a portfolio of ETFs.

%matplotlib inline

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

from pandas.io.data import DataReader

from datetime import datetime

import six

import universal as up

from universal import tools

from universal import algos

import logging

# we would like to see algos progress

logging.basicConfig(format=’%(asctime)s %(message)s’, level=logging.DEBUG)

import matplotlib as mpl

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

mpl.rcParams[’figure.figsize’] = (16, 10) # increase the size of graphs

mpl.rcParams[’legend.fontsize’] = 12

mpl.rcParams[’lines.linewidth’] = 1

default_color_cycle = mpl.rcParams[’axes.color_cycle’] # save this as we will want it back laterThis cell is purely environment and presentation setup for the experiments that follow; it doesn’t implement any trading logic itself but prepares the notebook so we can fetch price data, run the OLPS algorithms, and inspect their behavior clearly and reproducibly.

First, we enable inline plotting so that charts produced later appear directly in the notebook, which is important because we will be visually comparing performance traces and weight allocations for multiple algorithms. The core numerical and data-manipulation libraries (numpy, pandas) are loaded because the OLPS algorithms consume time-series price matrices and return vectorized portfolio updates and performance summaries; pandas’ DataReader is the intended mechanism here to pull historical ETF prices from online sources (so that raw market data flows into the experiment). A small compatibility helper (six) is present for cross-version support, and the universal package (aliased as up) plus its submodules tools and algos provide the OLPS implementations and helper functions (data preprocessing, transaction-cost handling, performance metrics) that we will use to run and evaluate each strategy.

We explicitly configure logging to DEBUG so we can observe algorithm progress messages as they run. OLPS algorithms are iterative and often emit diagnostic information at each step (rebalances, weight projections, exceptions); enabling debug-level logging helps us verify that updates are happening as expected and diagnose convergence or data issues while the algorithms process many time steps.

Finally, the matplotlib configuration is adjusted to prioritize readability for comparative plots: a larger figure size gives space for multiple time-series lines, increasing legend font size and line width improves clarity when many algorithms are plotted on the same axes, and the current color cycle is saved so we can restore or reuse the default palette later. These presentation choices make it easier to compare cumulative wealth curves and weight trajectories across a diversified set of ETFs, ensuring visual output is interpretable and consistent across runs. Overall, this block prepares the data pipeline, diagnostic visibility, and plotting aesthetics so that subsequent code can fetch ETF histories, run each OLPS algorithm from universal.algos, and produce clear side-by-side comparisons of their behavior and performance.

# note what versions we are on:

import sys

print(’Python: ‘+sys.version)

print(’Pandas: ‘+pd.__version__)

import pkg_resources

print(’universal-portfolios: ‘+pkg_resources.get_distribution(”universal-portfolios”).version)This short block is an explicit environment-check that runs at the start of an experiment so you, and anyone reproducing the work, know exactly which runtime and library implementations produced the results. First it queries and prints the active Python interpreter string; that gives the major/minor version and the build metadata which can affect language features, numeric behavior and binary wheel compatibility. Next it prints pandas’ reported version via the DataFrame library’s own __version__ attribute — that matters because pandas’ API, grouping/rolling semantics, and dtype handling have changed across releases and can subtly alter backtest data preparation and aggregation results. Finally it asks pkg_resources for the installed version of the universal-portfolios package, the specific OLPS implementation library you’re using; that version determines the concrete algorithm implementations, defaults, and bug fixes that will directly affect the portfolio updates and final performance numbers.

Why do this at the top of the notebook/script? Small differences in any of these components can change outcomes, make a result non-reproducible, or produce cryptic errors when others run your code. Recording versions when you compare OLPS algorithms over a diversified ETF universe ensures you can attribute discrepancies to code, data, or environment, and it speeds debugging when upgrading packages or moving between machines/CI. It also makes experiment logs self-contained: a reviewer can recreate the same stack or know which package upgrades might explain observed changes in algorithm behavior.

A couple of practical notes to keep the check robust: printing versions early prevents you from relying on implicit assumptions later, and you may want to include additional environment metadata (OS/platform, numpy/scipy versions, and a full requirements lockfile or pip freeze) for complete reproducibility. If you prefer a more modern API on recent Python versions, importlib.metadata or pkg_resources exceptions can be used to handle missing distributions gracefully; otherwise, capturing the outputs into an experiment artifact is a simple, effective habit to maintain reliable comparisons across OLPS runs.

Loading data

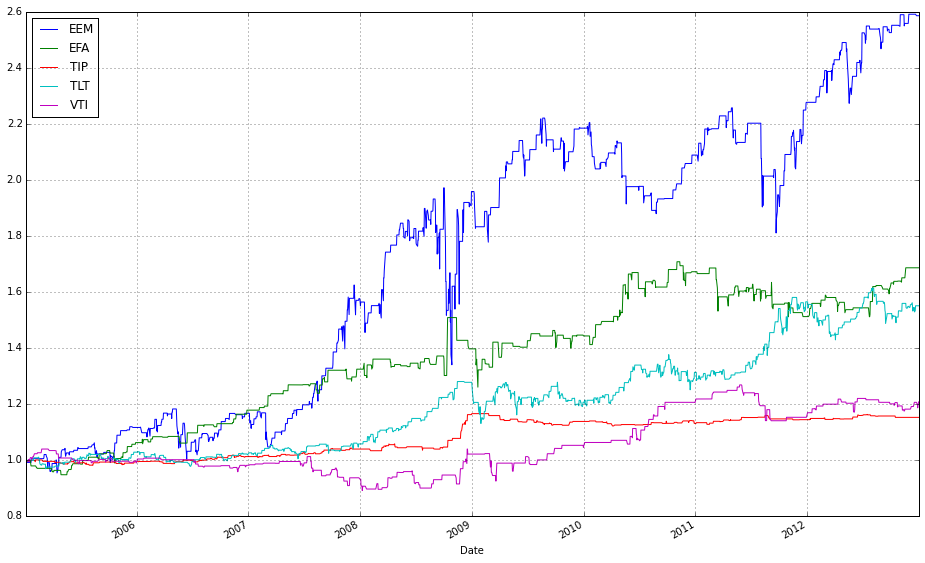

We use market data from 2005–2012 (inclusive; eight years) for training and data from 2013–2014 (inclusive; two years) for testing. For now, we accept each algorithm’s default parameters and treat the two periods as independent. In future work, we will optimize parameters on the training set.

# load data from Yahoo

# Be careful if you cange the order or types of ETFs to also change the CRP weight %’s in the swensen_allocation

etfs = [’VTI’, ‘EFA’, ‘EEM’, ‘TLT’, ‘TIP’, ‘VNQ’]

# Swensen allocation from http://www.bogleheads.org/wiki/Lazy_portfolios#David_Swensen.27s_lazy_portfolio

# as later updated here : https://www.yalealumnimagazine.com/articles/2398/david-swensen-s-guide-to-sleeping-soundly

swensen_allocation = [0.3, 0.15, 0.1, 0.15, 0.15, 0.15]

benchmark = [’SPY’]

train_start = datetime(2005,1,1)

train_end = datetime(2012,12,31)

test_start = datetime(2013,1,1)

test_end = datetime(2014,12,31)

train = DataReader(etfs, ‘yahoo’, start=train_start, end=train_end)[’Adj Close’]

test = DataReader(etfs, ‘yahoo’, start=test_start, end=test_end)[’Adj Close’]

train_b = DataReader(benchmark, ‘yahoo’, start=train_start, end=train_end)[’Adj Close’]

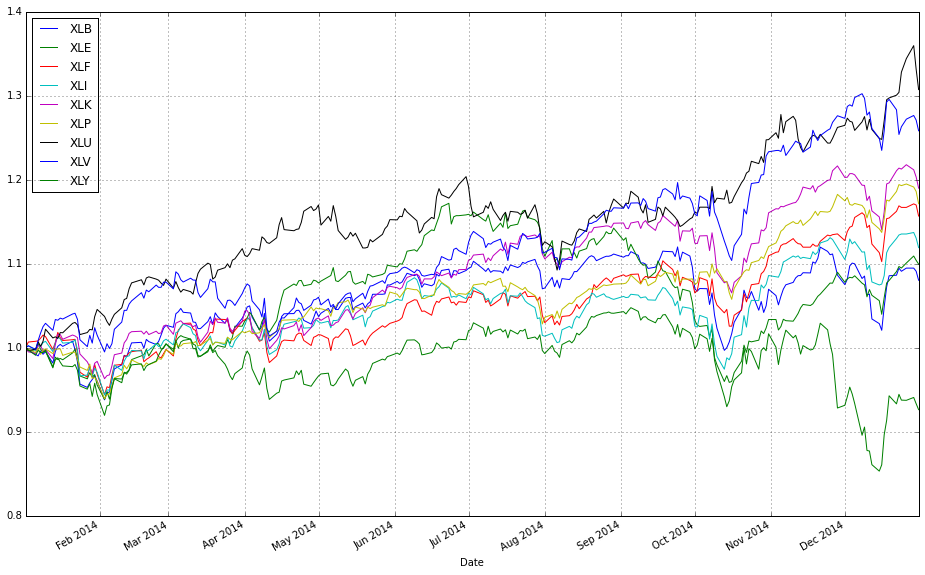

test_b = DataReader(benchmark, ‘yahoo’, start=test_start, end=test_end)[’Adj Close’]This block defines the universe, the reference allocation, the benchmark, the temporal split for evaluation, and then pulls the historical price series that the online portfolio selection (OLPS) experiments will operate on. The ETF list is the asset universe: broad-market, international, emerging, long-term and inflation-protected bonds, and real estate (VTI, EFA, EEM, TLT, TIP, VNQ). Those tickers are intentionally chosen to create a diversified test bed so that OLPS algorithms are evaluated across different risk/return drivers (equities vs bonds, growth vs inflation protection, real estate), which is important because many OLPS rules behave differently depending on cross-asset correlations and volatility regimes.

Right after the ticker list you see swensen_allocation — a constant rebalanced portfolio (CRP) weight vector derived from David Swensen’s “lazy” allocation. We keep that here as a baseline deterministic strategy: it’s the buy-and-hold/periodically-rebalanced allocation you will compare your OLPS outputs to. The comment warns that if you change the ETF ordering or membership, you must update this weight vector accordingly — the positions in the list are positional and must align with the tickers so that each weight maps to the intended ETF. Using a known, practitioner-oriented allocation as a baseline gives you an interpretable benchmark that captures a sensible, diversified long-term allocation rather than an arbitrary equal-weight CRP.

The code then establishes train and test date ranges. The training window (2005–01–01 to 2012–12–31) and testing window (2013–01–01 to 2014–12–31) are separated so you can calibrate or tune algorithms on historical data and then evaluate out-of-sample performance in a later period. This temporal separation preserves causality and avoids look-ahead bias. Also, these ranges span distinct market regimes (including the 2008 crisis in training and a post-crisis period in testing), which is helpful to see how algorithms learned in one regime generalize to another.

Finally, the DataReader calls fetch adjusted close prices for both the ETF universe and the benchmark (SPY) for the respective train/test periods. Pulling “Adj Close” is deliberate: adjusted prices account for corporate actions like dividends and splits, so returns computed from these series reflect total return and are comparable across time. The resulting objects will be time-indexed tables (dates × tickers) that the OLPS framework consumes to compute daily returns, update portfolio weights, and evaluate wealth trajectories. Note you should check for and handle non-trading days or missing values and ensure the benchmark series and ETF series are aligned on the same calendar before running comparisons; consistent ordering and indexing are essential so CRP weights map to the correct columns and performance metrics are computed on aligned return vectors.

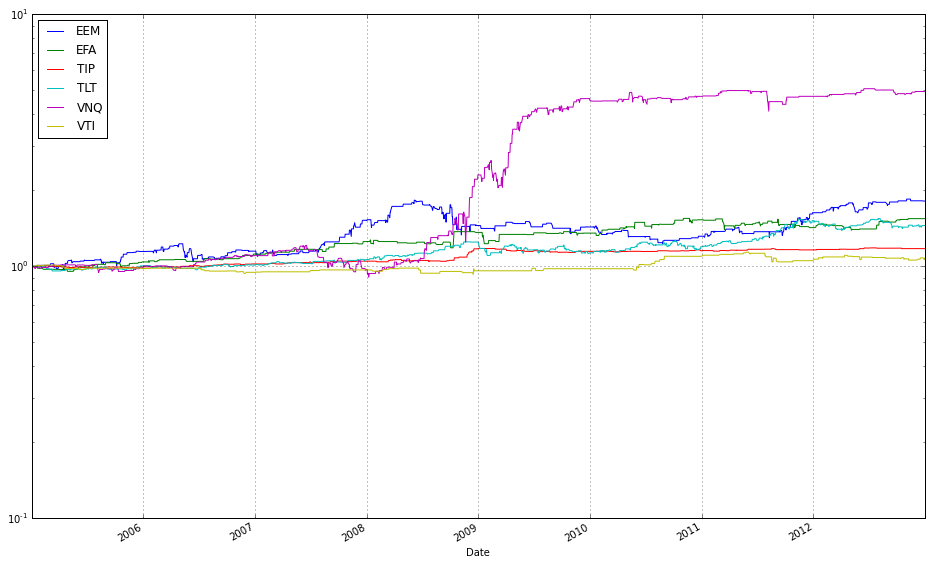

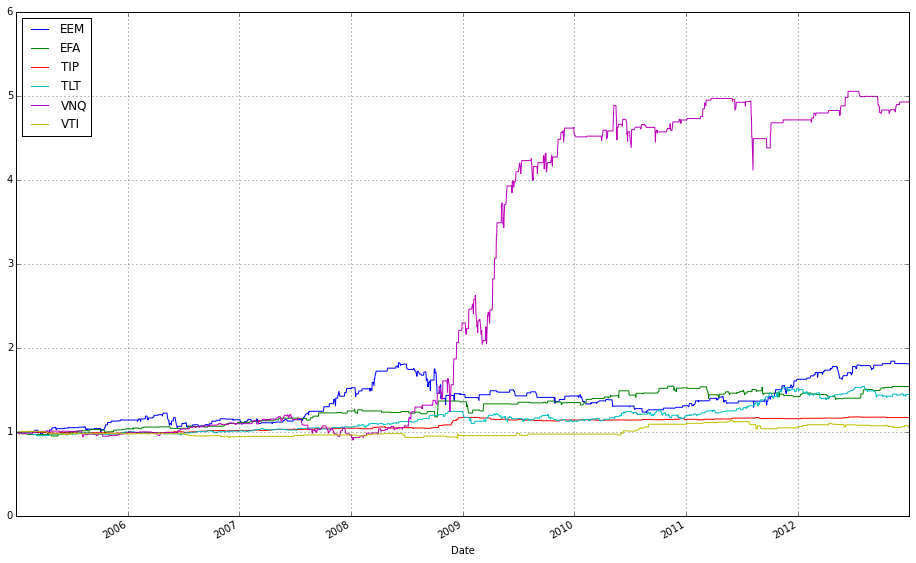

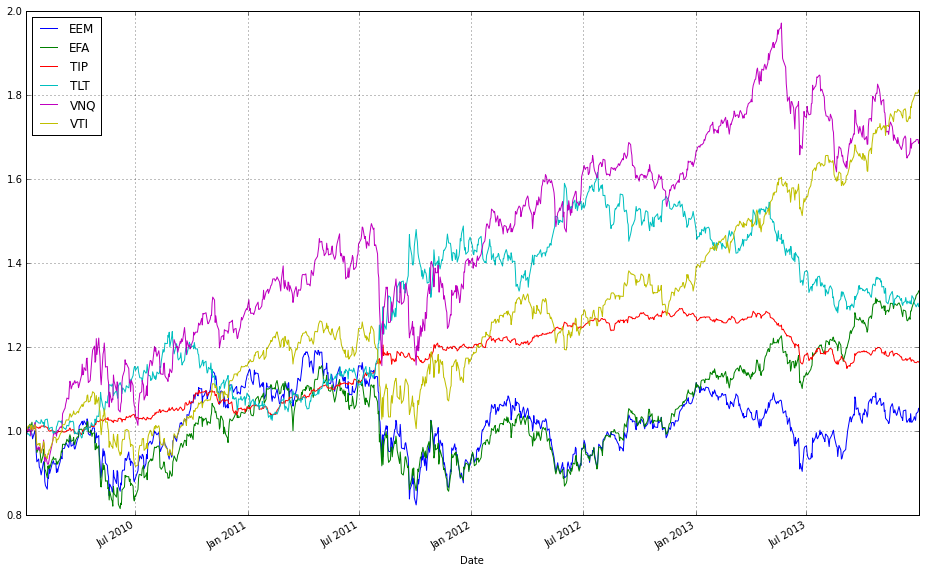

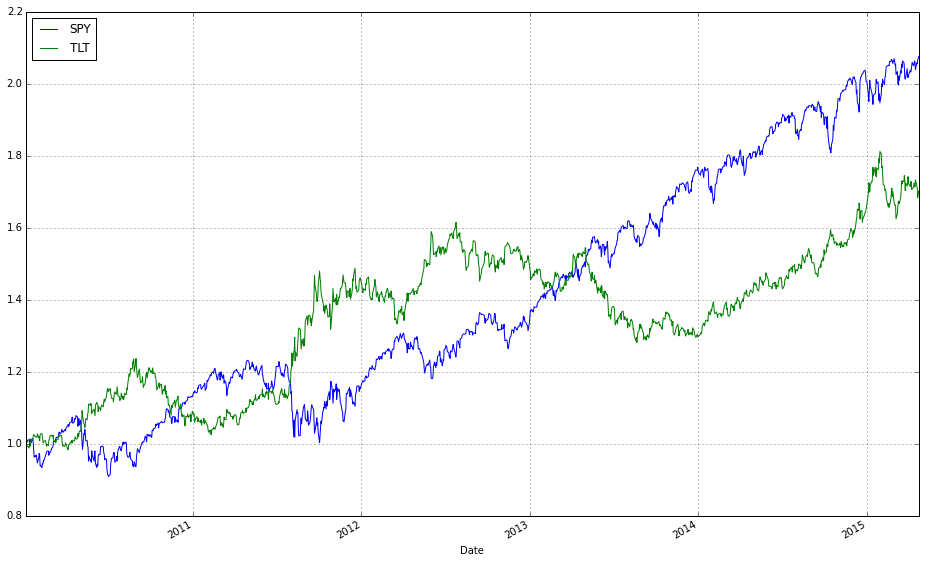

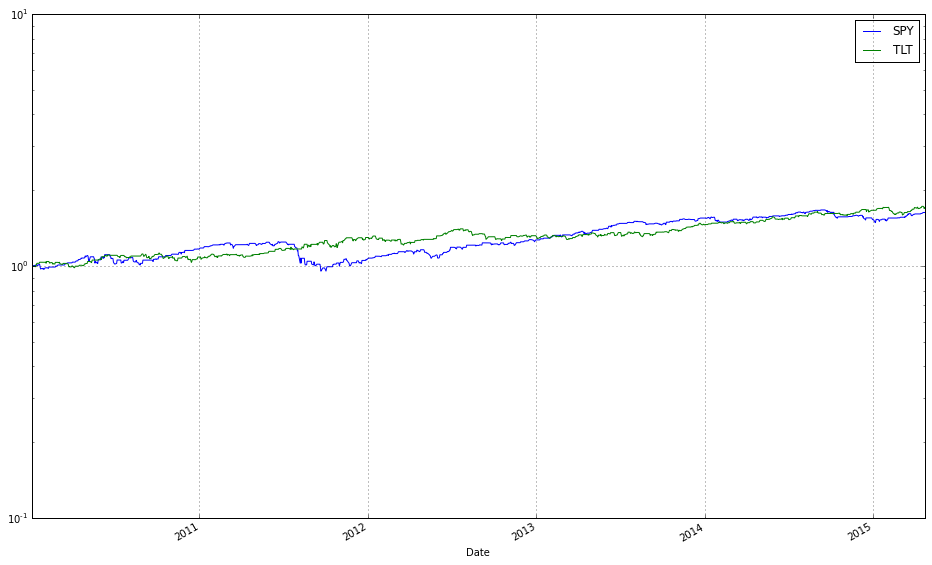

# plot normalized prices of the train set

ax1 = (train / train.iloc[0,:]).plot()

(train_b / train_b.iloc[0,:]).plot(ax=ax1)These two lines normalize each time series to a common starting point and then plot them on the same axes so you can visually compare relative returns over time. The expression train / train.iloc[0, :] takes the entire DataFrame of training prices and divides each column by its value at the first timestamp; this converts every instrument’s price series into a growth factor that starts at 1. Normalizing like this is important because ETFs have different absolute price levels and currencies — by forcing a common baseline you can compare proportional performance (how much each asset or strategy has multiplied) rather than raw price, which is what you care about when comparing online portfolio selection algorithms.

The plot call returns a Matplotlib Axes (ax1), and the second line overlays the normalized series from train_b on that same Axes by passing ax=ax1. That ensures both sets of series share the same x-axis (typically dates) and y-axis scaling so their trajectories are directly comparable. Note a few practical implications: pandas will align series by index when plotting, so mismatched dates can introduce NaNs or gaps; dividing by the first row assumes those first-row values are nonzero (otherwise you’ll get infinities); and NaNs in either DataFrame will propagate through the normalization. Overlaying in this way is a simple visual check of relative performance across diversified ETFs or alternative datasets/strategies before running more formal quantitative comparisons.

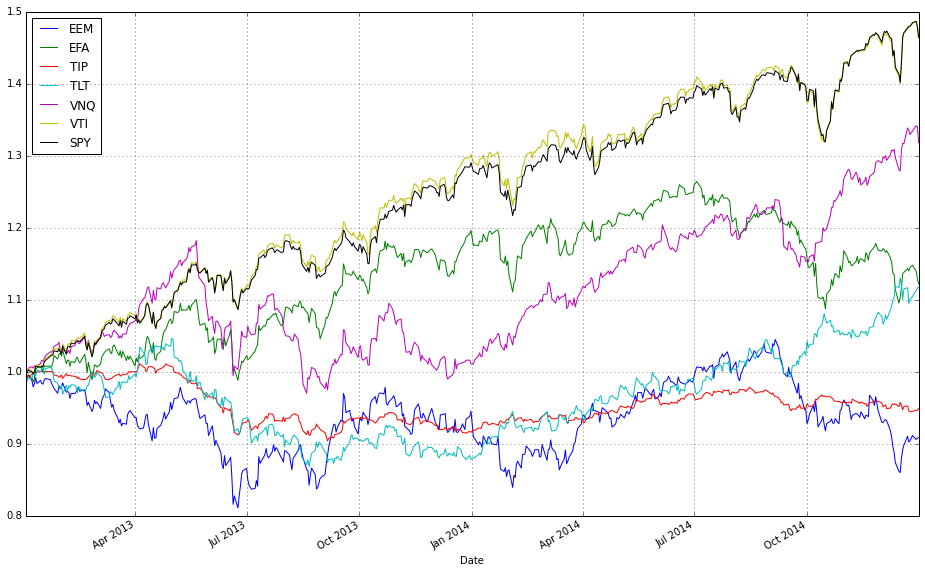

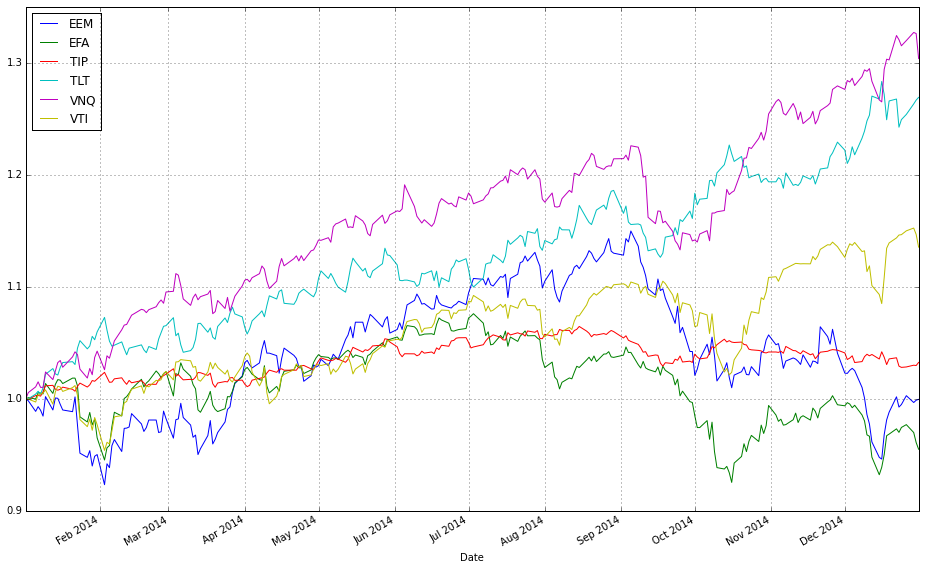

# plot normalized prices of the test set

ax2 = (test / test.iloc[0,:]).plot()

(test_b / test_b.iloc[0,:]).plot(ax=ax2)This pair of lines takes two multi-column price tables (test and test_b) and draws them on the same axes after converting each column into a relative growth series that starts at 1. Concretely, test / test.iloc[0,:] divides every column in the test DataFrame by that column’s first observed price (pandas aligns the first-row Series to each column), so each asset’s time series becomes “price relative to its initial price” — effectively the trajectory of one unit of capital invested at the first timestamp. That normalized DataFrame is plotted and the returned Matplotlib axes object is captured in ax2.

The second line repeats the same normalization for test_b, but passes ax=ax2 so the resulting curves are drawn on top of the previously created plot. Overlaying both normalized sets on a single axis forces them to share the same baseline and vertical scale, which makes it trivial to compare absolute growth factors across different ETFs or strategies regardless of their original price levels. In the context of comparing OLPS algorithms, this is exactly why we normalize: absolute prices differ across ETFs and would otherwise obscure which algorithm or ETF actually produced higher cumulative wealth; normalizing to the first observation converts raw prices into comparable cumulative-return-like series.

A couple of practical notes implicit in this code: because we divide by the first-row values, any zero or missing value at the first timestamp would cause division issues, so ensure the dataset has valid initial prices. Also, because .plot() uses the DataFrame index as the x-axis, you automatically get a time series view of performance, which is typically what you want when evaluating algorithmic wealth trajectories over a test period.

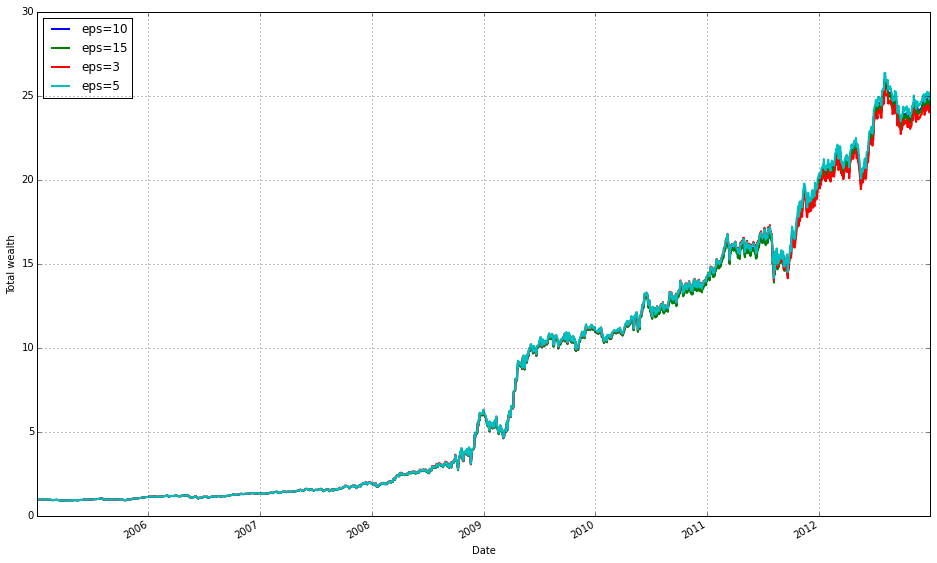

Comparing Algorithms

We train on market data spanning multiple years and evaluate out-of-sample over a shorter test period. To start, we use the default parameters for each algorithm and treat the training and testing intervals as two independent time periods. In future work, we will optimize the parameters on the training set.

#list all the algos

olps_algos = [

algos.Anticor(),

algos.BAH(),

algos.BCRP(),

algos.BNN(),

algos.CORN(),

algos.CRP(b=swensen_allocation), # Non Uniform CRP (the Swensen allocation)

algos.CWMR(),

algos.EG(),

algos.Kelly(),

algos.OLMAR(),

algos.ONS(),

algos.PAMR(),

algos.RMR(),

algos.UP()

]This small block constructs the set of online portfolio selection (OLPS) algorithm instances that the backtest will run against your ETF universe. Conceptually, each element in olps_algos is an instantiated strategy object that, given a price-relatives stream, will output a weight vector at each step; collecting their performance side-by-side is how we compare behavior across the diversified set of ETFs.

Start-to-finish, the list deliberately mixes several algorithmic families so the comparison covers a wide range of modeling assumptions and trading dynamics. The first two benchmarks — BAH (Buy-and-Hold) and BCRP (Best Constant Rebalanced Portfolio) — are critical anchors: BAH represents a passive, buy-and-hold policy for reference, while BCRP is the (in-sample) best fixed rebalanced portfolio and serves as a useful performance ceiling for constant-rebalanced strategies. CRP(b=swensen_allocation) is a non-uniform CRP initialized with a domain-specific strategic allocation (swensen_allocation); including it lets you see how a long-only strategic allocation (e.g., an institutional target mix) compares to adaptive OLPS methods and helps separate benefits from reallocation versus simply starting from a different weight vector.

The rest of the list intentionally spans common OLPS approaches so you can observe which assumptions work on ETFs. Multiplicative-update and first-order learners like EG (Exponentiated Gradient) and ONS (On-line Newton Step) adapt continuously to recent performance and tend to react quickly to trends; they are useful for momentum-like environments. Kelly-based approaches aim to maximize growth under an information-theoretic objective, which can produce aggressive position shifts when signals are strong. Algorithms that explicitly target mean-reversion or lead-lag effects — Anticor, PAMR, RMR, CWMR — try to exploit reversals or cross-asset correlations by transferring weight from recent winners to recent losers (or by robustly constraining that behavior), so they are included because ETFs frequently display sector rotation and relative mean reversion. Pattern- or memory-based methods such as CORN and BNN look for historical market states similar to the present and allocate according to those matched histories; they can capture recurring or seasonal ETF behavior that purely gradient methods miss. OLMAR (On-Line Moving Average Reversion) targets moving-average reversion/momentum at the portfolio level and often produces smoothed trades that can be robust to noise. UP (Universal Portfolio) aggregates across many CRPs and is asymptotically competitive with the best constant-rebalanced rule; it’s a useful “theoretical” baseline that is often computationally heavier but informative about long-run optimality.

Why this diversity matters: ETFs represent a mix of asset classes, sectors, and factor exposures, so there is no single generative model you can assume. By including mean-reversion, trend-following, pattern-matching, robust-statistics, second-order adaptive, and theoretical-universal strategies, you get coverage across the main hypotheses about how returns are generated. That variety helps you identify which structural behaviors (e.g., momentum, rotation, recurring patterns) drive performance in your ETF set rather than mistaking an algorithm’s inductive bias for a universally superior method.

A few practical implications to keep in mind while running the comparison: all of these objects will produce portfolio weight vectors that your backtester will convert into rebalancing trades, so turnover and transaction cost modeling will materially change relative rankings — algorithms that trade frequently (some mean-reversion or high-sensitivity methods) will suffer more under realistic costs. Also note that default hyperparameters may favor certain regimes; if you need a fair comparison, tune or at least sanity-check key knobs (e.g., aggressiveness/tolerance in PAMR, window sizes for CORN/OLMAR). Finally, the explicit CRP(b=swensen_allocation) case is an important control: it lets you answer whether adaptive rebalancing actually beats a carefully chosen static institutional allocation on this ETF universe.

# put all the algos in a dataframe

algo_names = [a.__class__.__name__ for a in olps_algos]

algo_data = [’algo’, ‘results’, ‘profit’, ‘sharpe’, ‘information’, ‘annualized_return’, ‘drawdown_period’,’winning_pct’]

metrics = algo_data[2:]

olps_train = pd.DataFrame(index=algo_names, columns=algo_data)

olps_train.algo = olps_algosThis block constructs a small table that ties each OLPS algorithm instance to its backtest outputs and a fixed set of performance metrics so we can compute, compare, and present results consistently across a diversified set of ETFs.

First, we derive a human-readable row index: algo_names = [a.__class__.__name__ for a in olps_algos]. Instead of using opaque ids or memory addresses, we use each instance’s class name so the DataFrame rows are labeled with meaningful algorithm names when we print, sort or plot results. That makes downstream comparison and reporting much easier.

Next, algo_data defines the schema for the table: the first two columns are ‘algo’ (to store the original instance) and ‘results’ (to store raw backtest outputs), followed by concrete performance fields (‘profit’, ‘sharpe’, ‘information’, ‘annualized_return’, ‘drawdown_period’, ‘winning_pct’) that we will compute from the results. Immediately after we take metrics = algo_data[2:], creating a slice that isolates just the numeric metric names; this is convenient when iterating to compute or format only the performance values, separating them from the object and raw-results columns.

We then instantiate a pandas DataFrame with olps_train = pd.DataFrame(index=algo_names, columns=algo_data). Creating the DataFrame with the algorithm names as the index commits to a stable, readable row structure up front, and reserving the columns makes it explicit which outputs will be produced. Note that the DataFrame will hold Python objects (dtype=object) for the ‘algo’ and ‘results’ columns — intentional, because we want to keep references to algorithm instances and to whatever complex result objects the backtester returns.

Finally, olps_train.algo = olps_algos assigns the list of algorithm instances into the ‘algo’ column so each row contains the corresponding instance that produced the results. This preserves object references so you can later call methods on an algorithm (e.g., re-run, inspect parameters) directly from the table. A couple of practical notes: the order of olps_algos must match algo_names (it does here because algo_names was derived from that list), and assigning a list into a DataFrame column requires matching lengths — otherwise pandas will raise an error. After this block, the intended flow is clear: run each algorithm’s backtest, store the returned object into ‘results’, compute the metric values (iterating over metrics) and populate those columns so the DataFrame becomes the canonical comparison table for ranking, plotting, or exporting the performance of the OLPS algorithms across the ETF universe.

At this point, we could train each algorithm to identify its optimal parameters.

# run all algos - this takes more than a minute

for name, alg in zip(olps_train.index, olps_train.algo):

olps_train.ix[name,’results’] = alg.run(train)This loop is the core step where each online portfolio selection (OLPS) algorithm in olps_train is executed on the training dataset and its output is attached back to the dataframe so we can compare algorithms side-by-side. olps_train is acting as a small registry: each row represents an algorithm (the index is the algorithm name) and the ‘algo’ column holds an algorithm object that implements a run(train) method. The loop zips the dataframe index with that column so you get the index label (name) paired with the corresponding algorithm object; for each pair it calls alg.run(train), which performs the algorithm’s backtest/fit on the supplied training series of ETF prices and returns a results payload (typically a performance object containing returns, risk metrics, weight time series, diagnostics, etc.). That returned payload is then written into the same registry under the ‘results’ cell for that named row, which preserves the association between algorithm metadata and its concrete results for later comparison and reporting.

Why this structure: running every algorithm on the same train set ensures a consistent basis for comparing performance across a diversified ETF universe. Storing results back into olps_train keeps metadata and outputs coupled so downstream steps (ranking, plotting, selection) can easily access both the algorithm object and its output. The code is sequential and synchronous: each alg.run is executed in order, which is deterministic and avoids concurrency issues that could arise if algorithms share global state, but it also explains the comment about runtime — these runs can be computationally expensive (simulating rebalanced portfolios, computing metrics, possibly performing inner optimization) so the whole loop can take a minute or more.

A few practical considerations to keep in mind: .ix is deprecated in modern pandas — prefer .loc[name, ‘results’] or .at[name, ‘results’] for a clear, stable assignment. Repeated DataFrame writes in a loop can be slower than collecting results in a list/dict and assigning the column in one operation; if performance matters, run all alg.run calls into a list and set olps_train[‘results’] = results_list afterwards. Add try/except around alg.run if you want the loop to continue when a single algorithm errors, and consider adding a progress indicator or parallelism (only if alg.run is thread/process safe and deterministic) to reduce wall-clock time. Finally, be mindful of memory: results objects can be large (time series of weights); if you only need summary metrics for comparison, store those instead or serialize the full objects to disk. Also ensure reproducibility for any stochastic algorithms by setting seeds inside alg.run before executing.

# Let’s make sure the fees are set to 0 at first

for k, r in olps_train.results.iteritems():

r.fee = 0.0This loop walks every result object produced by the training run and forces its fee attribute to zero. Practically, olps_train.results is a mapping of algorithm identifiers to their result containers; the code iterates through that mapping and mutates each result in place so any downstream performance calculations read a fee of 0.0. Because the change happens on the result objects themselves, it immediately affects later metrics, plots, or comparisons that use those results.

We do this to remove transaction costs as a confounding factor in initial experiments. Transaction fees (or slippage models) directly reduce realized returns and bias algorithm ranking toward approaches with lower turnover. By zeroing fees up front, you can observe the pure allocation and rebalancing behavior of each OLPS algorithm on the ETF universe — essentially measuring strategy efficacy in an idealized, frictionless market. This is useful for debugging, sanity-checking logic, and comparing core strategy differences (e.g., aggressive versus conservative rebalancing) before bringing in market frictions that complicate interpretation.

Be aware of the semantic implications: this is an in-place mutation of the stored result objects, so the original fee values (if any) are lost unless they were preserved elsewhere. If your experiment plan includes later runs with realistic fees, either restore the saved originals or recompute the results fresh with fees set appropriately. Also remember that fees interact strongly with turnover and rebalancing frequency, so a zero-fee comparison should be treated as a baseline — follow up with sensitivity testing across a range of realistic fee/slippage settings to assess robustness of the OLPS algorithms on the diversified ETF set.

# we need 14 colors for the plot

n_lines = 14

color_idx = np.linspace(0, 1, n_lines)

mpl.rcParams[’axes.color_cycle’]=[plt.cm.rainbow(i) for i in color_idx]This small block’s job is to create a predictable set of distinct colors for plotting the many algorithm traces we’ll display when comparing OLPS strategies across a diversified ETF universe. We start by deciding how many distinct lines we need (n_lines = 14), then generate that many evenly spaced sampling points along the normalized colormap domain using np.linspace(0, 1, n_lines). Those sampling points are used to index a continuous colormap (plt.cm.rainbow), producing a list of RGBA tuples — one color per algorithm — so adjacent algorithms are assigned hues that are spread across the full spectrum rather than clustered in one region.

Assigning this list to mpl.rcParams[‘axes.color_cycle’] makes the color selection global for subsequent plotting calls: whenever matplotlib draws multiple lines in a single axes, it will cycle through this predefined list, which enforces consistent and repeatable color-to-algorithm mapping across plots and subplots. That consistency is important for our comparisons, because we want each OLPS algorithm to keep the same color across different ETF charts and figures so readers can quickly identify relative performance patterns.

Two practical notes about the choice and technique: sampling a continuous colormap evenly gives visual separation between many lines, but the rainbow colormap is not perceptually uniform and can be problematic for colorblind readers. Also, newer matplotlib versions deprecate the axes.color_cycle rcParam in favor of axes.prop_cycle (used together with cycler), so you may want to switch to a qualitative palette (for example ‘tab20’ or a seaborn color_palette) and set axes.prop_cycle = cycler(‘color’, […]) to achieve better accessibility and forward compatibility.

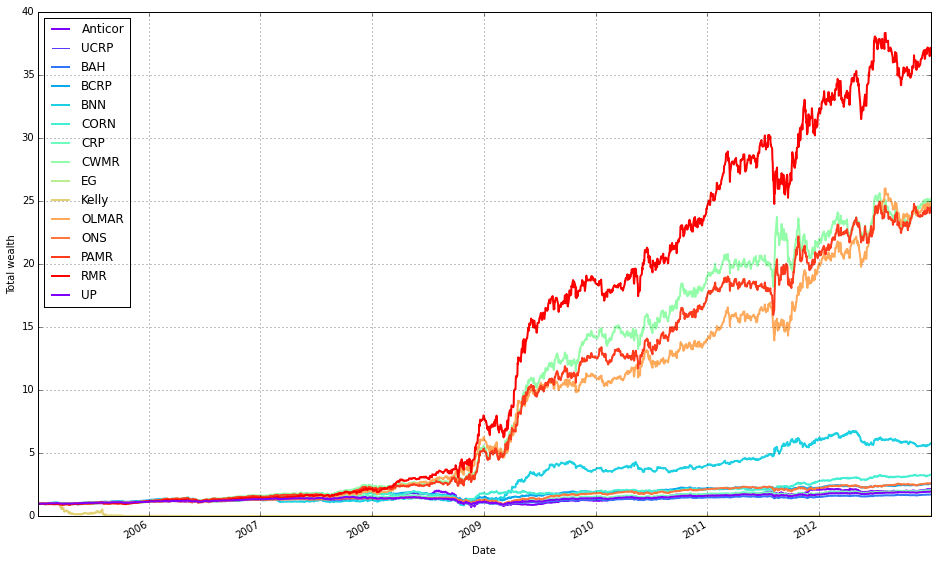

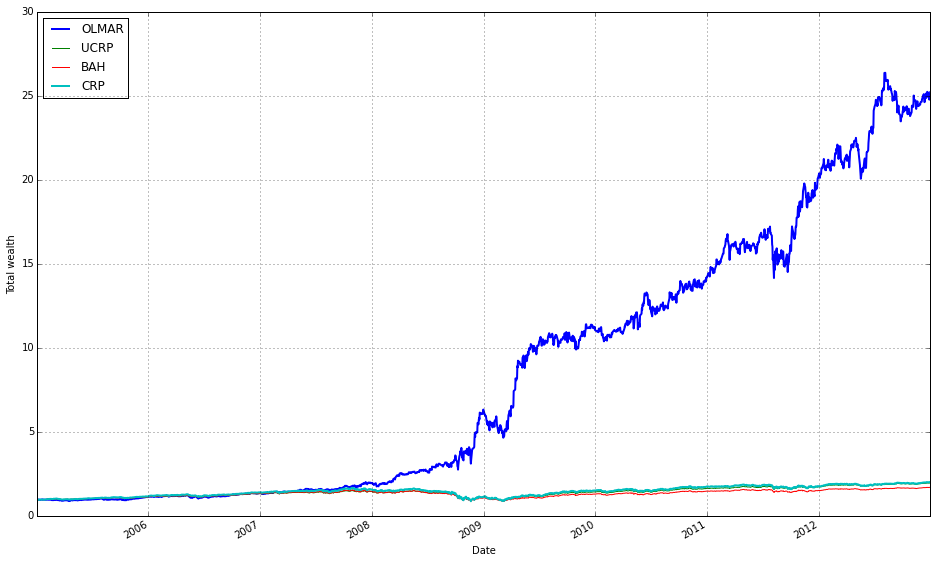

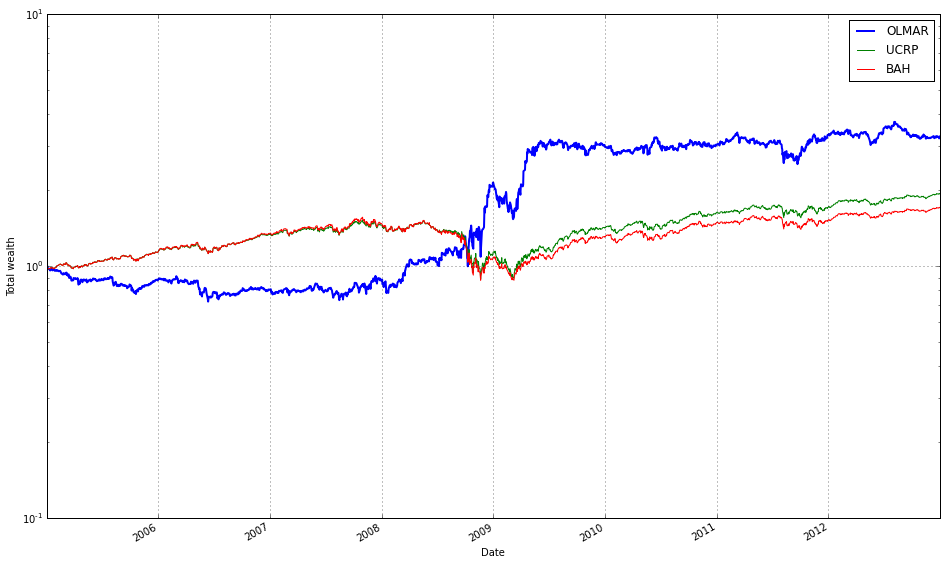

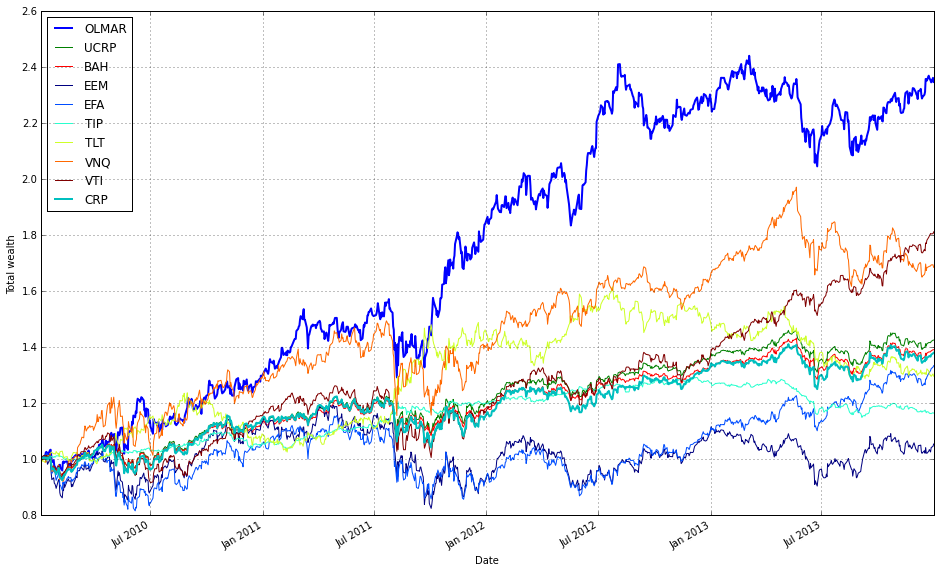

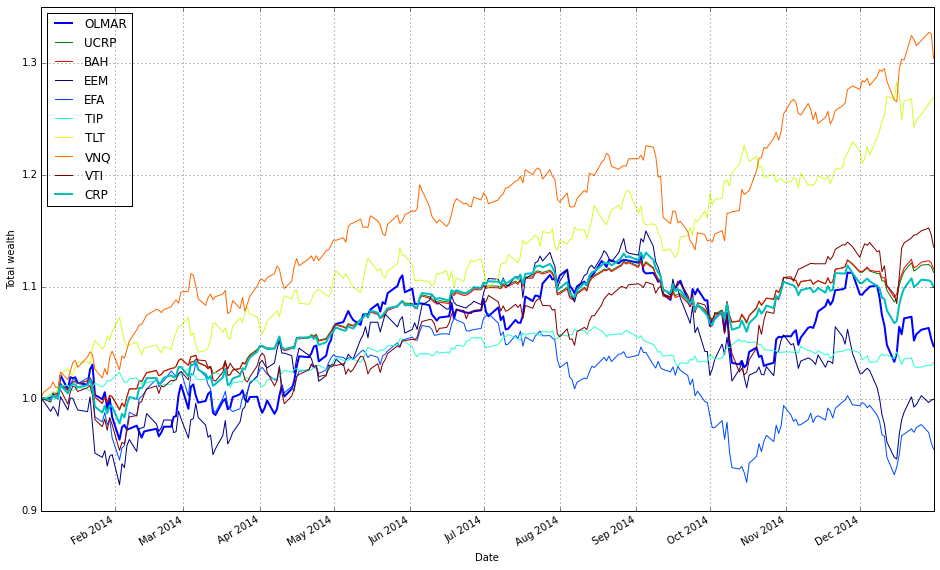

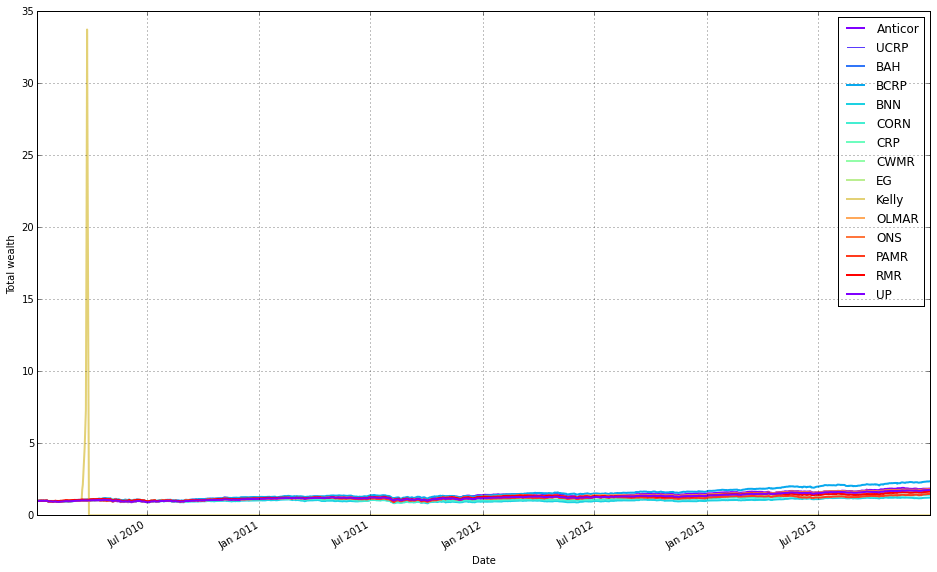

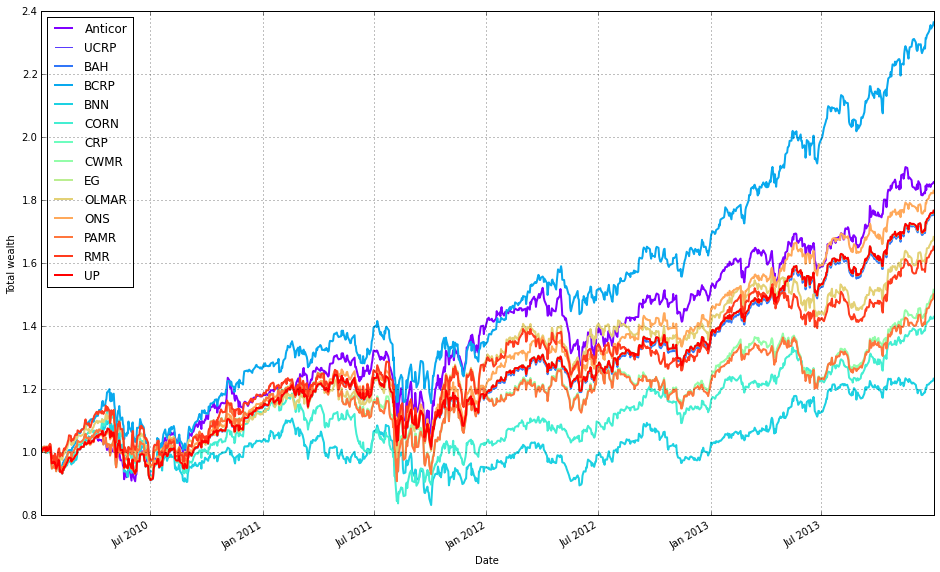

# plot as if we had no fees

# get the first result so we can grab the figure axes from the plot

ax = olps_train.results[0].plot(assets=False, weights=False, ucrp=True, portfolio_label=olps_train.index[0])

for k, r in olps_train.results.iteritems():

if k == olps_train.results.keys()[0]: # skip the first item because we have it already

continue

r.plot(assets=False, weights=False, ucrp=False, portfolio_label=k, ax=ax[0])This block produces a single comparative plot of the portfolio-level performance curves for the OLPS experiments, treating the simulations as if there were no transaction fees so we see raw algorithm returns. The first plotted series is used as the anchor because the code needs an axes object from an initial plot call to draw all remaining curves onto the same figure (so they share the same axes, limits, and legend).

Concretely, the first plot call draws only the portfolio-level cumulative return for the first result entry and enables the ucrp trace (Uniform Constant Rebalanced Portfolio) so that the UCRP baseline appears on the figure. assets=False and weights=False deliberately suppress per-asset and weight-evolution subplots because the intent here is a clean, single-panel comparison of overall portfolio performance across algorithms; portfolio_label assigns a readable legend entry tied to that first result.

The loop then walks through every result in olps_train.results and skips the first element (because it was already plotted). For each subsequent result it calls r.plot again with assets=False and weights=False so we only plot portfolio returns, and ucrp=False to avoid re-plotting the same baseline. Passing ax=ax[0] overlays each algorithm’s portfolio curve onto the same axes instance returned by the first call; this ensures consistent scaling and direct visual comparability of the return trajectories and legend entries (portfolio_label=k gives each curve a distinct label).

A couple of implementation notes relevant to robustness: the pattern of grabbing the “first” element by comparing to olps_train.results.keys()[0] and using iteritems() suggests an ordered mapping (or an older pandas-style Series); depending on the runtime environment, keys() may not be indexable in modern Python dicts, so the code assumes a container type that preserves ordering or supports that indexing. Finally, because the plot is created “as if we had no fees,” these curves show frictionless performance — useful for a clean algorithmic comparison, but remember that high-turnover methods may perform materially worse once transaction costs are applied.

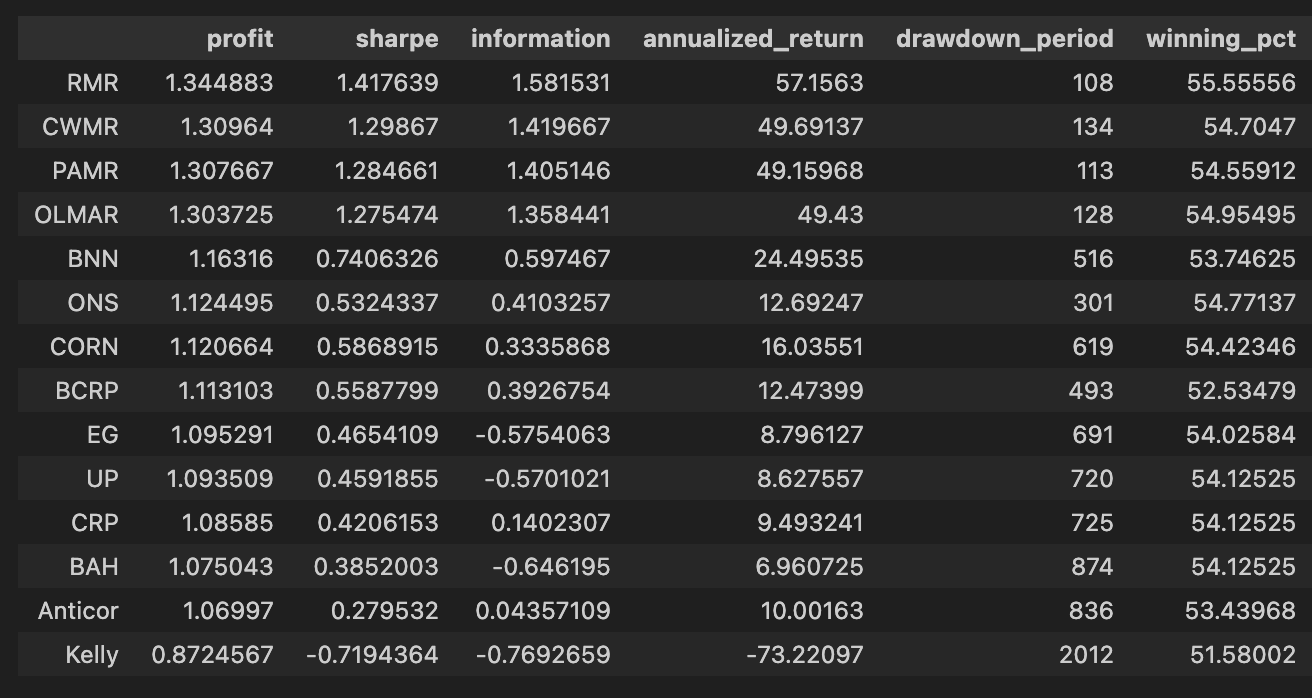

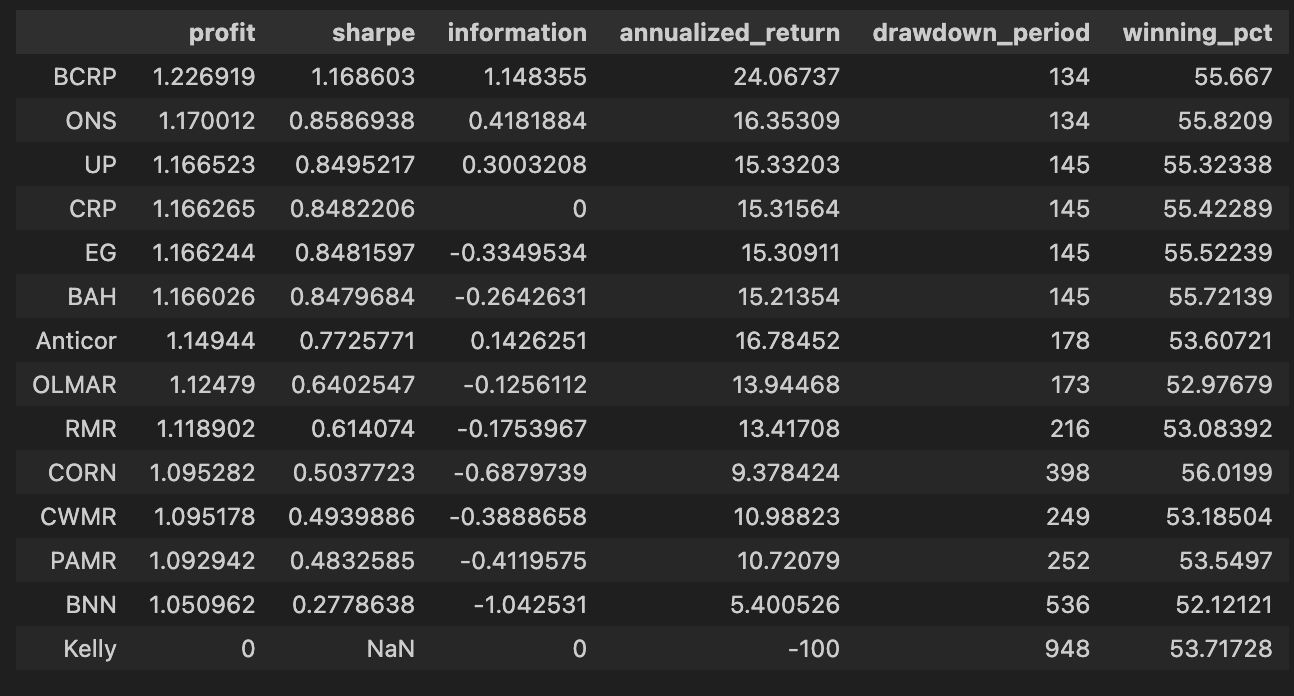

def olps_stats(df):

for name, r in df.results.iteritems():

df.ix[name,’profit’] = r.profit_factor

df.ix[name,’sharpe’] = r.sharpe

df.ix[name,’information’] = r.information

df.ix[name,’annualized_return’] = r.annualized_return * 100

df.ix[name,’drawdown_period’] = r.drawdown_period

df.ix[name,’winning_pct’] = r.winning_pct * 100

return dfThis small function pulls per-algorithm performance objects out of a container on the input DataFrame and materializes a compact set of comparison metrics back into the DataFrame so the caller can easily rank and display OLPS algorithms across the ETF universe. Concretely, it iterates over df.results (a mapping from algorithm name → result object), and for each algorithm it writes six summary statistics into the DataFrame row keyed by that algorithm name: profit, sharpe, information, annualized_return, drawdown_period, and winning_pct. The loop is the story of the data: read the result object for an algorithm, extract the fields that matter for algorithm comparison, transform a couple of them into human-friendly units, and store them on the tabular summary.

Each field stored has an explicit intent. profit is assigned from r.profit_factor (a profitability metric such as gross profit divided by gross loss) to surface raw profit efficiency; sharpe is the risk‑adjusted return; information is the active-return metric versus a benchmark; drawdown_period captures the duration of the worst drawdown episode (a tail‑risk indicator); annualized_return is converted from a fractional value to a percentage by multiplying by 100 (we do this because stakeholders expect yearly returns in percent); winning_pct is likewise converted from a decimal fraction to a percentage for easier interpretation and display. These choices let us compare algorithms along dimensions of absolute profitability, risk‑adjusted performance, benchmark relevance, downside duration, and consistency — which are the practical axes for selecting an OLPS method on a diversified set of ETFs.

A couple of behavioral notes that matter when you use this function: it mutates df in place (it updates/creates cells on the passed DataFrame) and then returns the same DataFrame reference. The code assumes each result object r exposes the named attributes; if any attribute is missing you’ll get an attribute error. It also uses df.ix[…] for assignment; in modern pandas code you should prefer explicit label-based accessors like df.loc[name, col] or df.at[name, col] to avoid ambiguity and to be robust to pandas API changes. Finally, if you plan downstream numerical operations or plotting, you may want to coerce these columns to numeric types and handle missing values or outliers ahead of visualization.

In short: this function is the bridge between algorithmic run objects and the tabular comparison used to evaluate OLPS strategies on the ETF set — it extracts the metrics that matter, normalizes presentation for people (percentages), and writes the summary back into the DataFrame so you can sort, filter, and visualize algorithm performance.

olps_stats(olps_train)

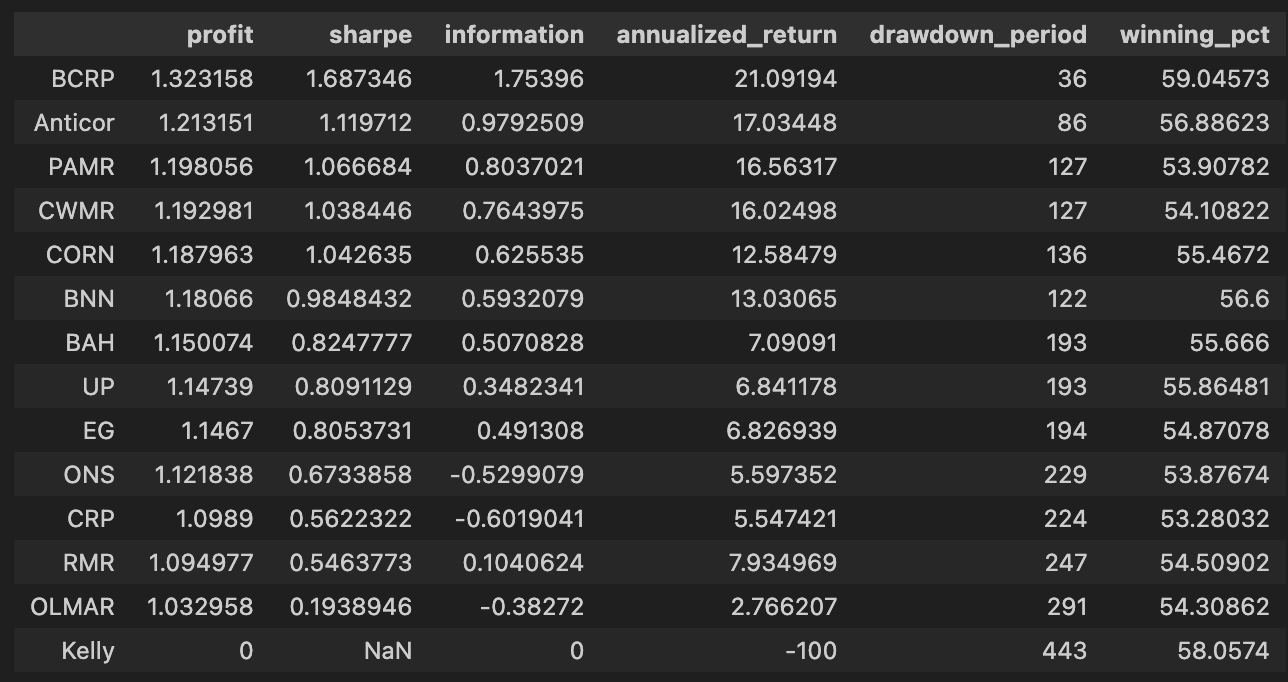

olps_train[metrics].sort(’profit’, ascending=False)First, olps_stats(olps_train) is the analytics step that computes the performance metrics we need to compare OLPS algorithms across the ETF universe. Conceptually this function takes the raw olps_train results — typically a table of per-algorithm, per-period returns (and possibly per-ETF breakdowns) — and reduces them into the standard performance measures: cumulative profit, annualized return, volatility or Sharpe, max drawdown, turnover, transaction costs, and any other summary statistics you’ve defined. We run this before any ranking because these derived columns are what let us meaningfully compare different algorithms; without computing them you only have low-level returns that are hard to rank or filter on a common basis. Note that implementations vary: some olps_stats return a new summary table, others augment/mutate olps_train in-place — be explicit in your code about which behavior you rely on.

The second line, olps_train[metrics].sort(‘profit’, ascending=False), is the presentation/ranking step. Here you select only the columns listed in the metrics variable (so the output is a compact table of the performance fields you care about) and then sort the rows by the profit column in descending order. Sorting by profit places the highest cumulative-return algorithms at the top so you can quickly identify candidates for deeper inspection. This is a pragmatic first-pass filter: profit is intuitive and useful for shortlisting, but it is not sufficient by itself — you should always cross-check the top entries against risk-adjusted measures (Sharpe, drawdown), trading frictions (turnover, transaction counts), and look for signs of overfitting.

Small but important operational points tied to those two lines: ensure olps_stats has executed successfully and produced the profit column before sorting (otherwise the sort will fail or return unexpected results), and be aware of whether the .sort call returns a new view or mutates the object in-place so you don’t inadvertently lose ordering or overwrite data. Also consider NaN handling and ties when sorting (decide how to break ties or whether to drop incomplete rows). Finally, remember that ranking by a single metric is just the start of model comparison on a diversified ETF set — use this ranked table to drive downstream checks (per-ETF performance heterogeneity, time-series stability, and transaction burden) before promoting any algorithm.

# Let’s add fees of 0.1% per transaction (we pay $1 for every $1000 of stocks bought or sold).

for k, r in olps_train.results.iteritems():

r.fee = 0.001This loop walks through the set of algorithm results stored in olps_train.results and sets a transaction-cost parameter on each result object. Concretely, for every algorithm entry (k) and its corresponding result container (r), it assigns r.fee = 0.001, which encodes a 0.1% cost per transaction (equivalently $1 for every $1,000 traded). The code is intentionally mutating each result object in place so that downstream performance calculations will include this cost.

Why we do this: transaction fees materially change algorithm rankings when comparing online portfolio selection (OLPS) strategies, especially across a diversified basket of ETFs. Many OLPS algorithms rebalance frequently; without realistic fees you overestimate net returns and favor high-turnover methods. By applying the same proportional fee to every algorithm before computing wealth/return trajectories, we make the comparison fair and reflective of execution costs. The choice of 0.001 models a simple proportional commission; how it is applied (per side, per round-trip, or per trade) depends on the wealth-update logic elsewhere in the OLPS framework, but placing this attribute here ensures that fee-aware accounting is consistently used by that logic.

A couple of practical implications: because the assignment is done on the training results object, any evaluation, tuning, or selection done after this point will reflect net performance (post-fees). Also, mutating r directly means all consumers of these result objects will see the fee; if you needed fee-free metrics as well, you’d need to keep a separate copy. Finally, ensuring the same fee across algorithms isolates transaction-cost sensitivity as the variable of interest, rather than conflating it with differing cost assumptions.

# plot with fees

# get the first result so we can grab the figure axes from the plot

ax = olps_train.results[0].plot(assets=False, weights=False, ucrp=True, portfolio_label=olps_train.index[0])

for k, r in olps_train.results.iteritems():

if k == olps_train.results.keys()[0]: # skip the first item because we have it already

continue

r.plot(assets=False, weights=False, ucrp=False, portfolio_label=k, ax=ax[0])This block is building a single overlaid plot of portfolio performance for a set of OLPS runs so you can directly compare their after-fee results on the same axes. First it grabs the very first result from olps_train.results and calls its plot method with assets=False and weights=False so the plot call renders only the portfolio/wealth curve (we hide per-asset and weight subplots to keep the figure focused). The argument ucrp=True tells that first call to include the UCRP (uniform constant rebalanced portfolio) baseline on the same figure, and portfolio_label assigns a human-readable legend entry using that result’s key. The returned value from that first plot call contains the matplotlib axes object(s); the code saves that into ax so subsequent curves can reuse the same axes.

Next, the loop iterates every result in olps_train.results and skips the first entry because it’s already plotted. For each remaining result it calls r.plot again with the same assets/weights flags to produce only the portfolio curve, but with ucrp=False so we don’t draw the baseline repeatedly. It passes ax=ax[0] to force the new curve to be drawn on the same primary axes created earlier, ensuring all wealth trajectories are overlaid and share the same scale and legend. portfolio_label=k tags each curve with its algorithm name in the shared legend, making visual comparison straightforward.

Why this matters: overlaying the curves on a single axis is the most direct way to compare relative after-fee performance, drawdowns and divergence between algorithms across the diversified ETF universe. Including the UCRP baseline once provides a consistent, interpretable benchmark without cluttering the plot. Hiding asset/weight subplots reduces visual noise so you focus on the business question — how different OLPS strategies perform net of transaction costs — rather than on per-asset weights.

A couple of practical notes to keep the code robust: the approach depends on the specific structure returned by .plot (ax being indexable) and on how olps_train.results exposes its first key; if you port this between Python versions or different result objects, make sure to retrieve the first key/axes in a version-safe way and confirm the shape of ax before indexing ax[0].

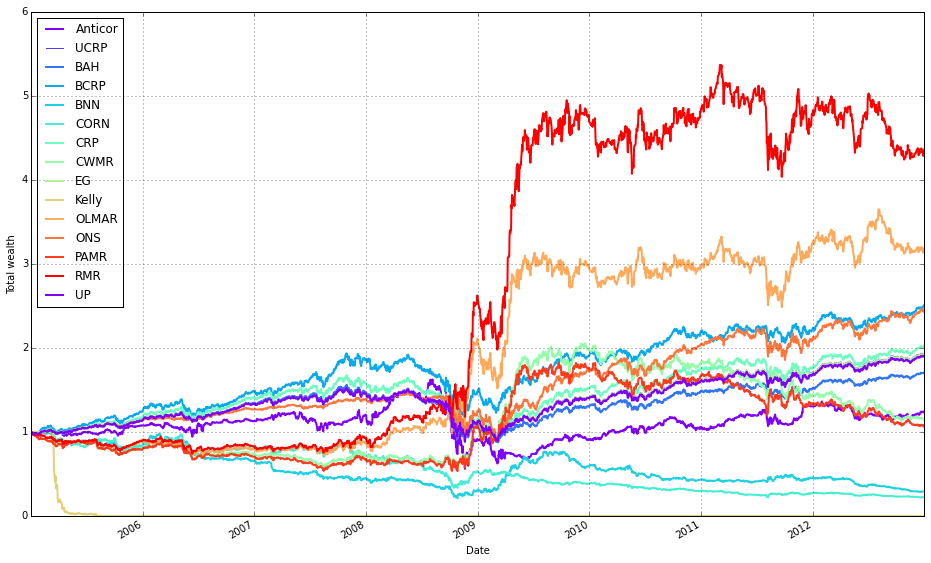

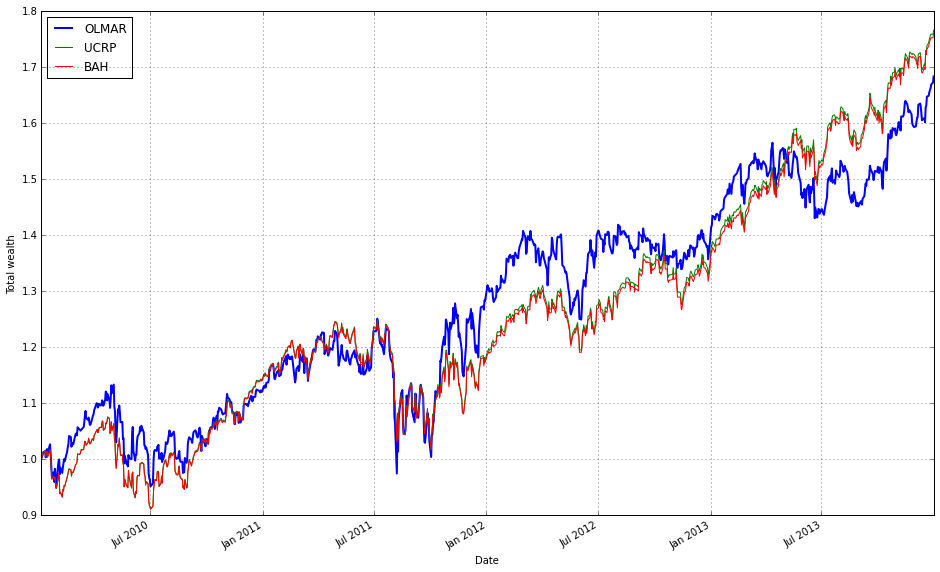

Note how Kelly crashes immediately, while RMR and OLMAR rise to the top after a period of high volatility.

olps_stats(olps_train)

olps_train[metrics].sort(’profit’, ascending=False)First, we call olps_stats(olps_train) to produce the performance summaries that we need to compare algorithms. In practice this function takes the raw training output for each OLPS variant — typically a time series of portfolio weights and per-period returns across the diversified ETF universe — and reduces it into a set of scalar metrics per algorithm. Those metrics normally include total profit (cumulative return), annualized return, annualized volatility, Sharpe ratio, maximum drawdown, turnover, and possibly metrics that account for transaction costs or leverage. The reason we run this aggregation step up front is that the raw time-series data is not directly comparable across algorithms: aggregating into a common set of statistics normalizes the different outputs so we can rank and reason about trade-offs (return vs. risk vs. trading friction) on a common footing.

The next line, olps_train[metrics].sort(‘profit’, ascending=False), selects the metric columns we care about and sorts the algorithms by the profit column in descending order. Functionally this is the leaderboard step: after olps_stats has computed each algorithm’s cumulative profit, we surface the highest absolute performers first so we can quickly see which OLPS strategies delivered the largest nominal gain on the training period. Sorting by profit is useful for an initial ranking because it highlights raw return performance, but it’s a deliberate, narrow choice — it does not account for risk, drawdown, or transaction costs. In the context of comparing OLPS algorithms for a diversified ETF set, this sorting is therefore an initial screening mechanism rather than a final decision rule.

A couple of practical notes that motivate why the two steps are separated: olps_stats should be run before any sorting or selection so that profit (and other derived metrics) exist and are calculated consistently (same time window, same cost assumptions, same rebalancing rules). Also, because we often want to inspect multiple metrics for the same ordering, we select olps_train[metrics] (the subset of columns) and then sort; that keeps the output compact and focused on comparators. Finally, remember that a single-column sort by profit can be misleading — after this quick ranking you should follow up by inspecting risk-adjusted measures (Sharpe, max drawdown) and operational metrics (turnover, estimated slippage/fees) to make a robust choice among OLPS candidates.

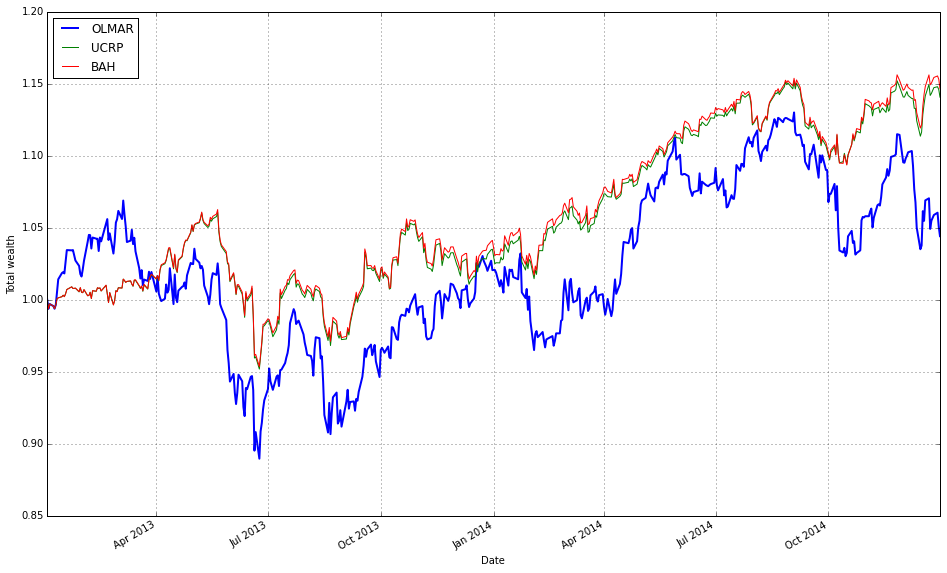

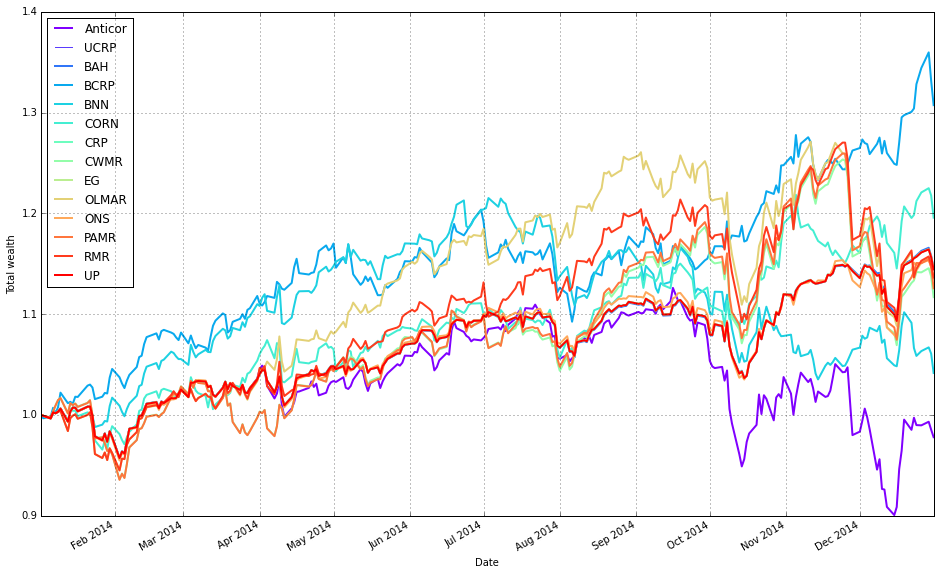

Run on the test set

Instructions for running on the test set.

# create the test set dataframe

olps_test = pd.DataFrame(index=algo_names, columns=algo_data)

olps_test.algo = olps_algosThis block is creating the empty results table that we’ll populate as we run each OLPS algorithm against the ETF universe, and it immediately attaches the algorithm implementations to their corresponding rows so later steps can execute them or reference metadata. First, pd.DataFrame(index=algo_names, columns=algo_data) constructs a table whose rows represent algorithms (indexed by algo_names) and whose columns represent the pieces of data or metrics we care about for comparison (algo_data — typically ETF tickers, per-ETF performance metrics, or summary statistics). Because we only supply axes, the cells start out as NaN; that is intentional: we’re reserving the two-dimensional layout so that when a backtest or evaluation runs we can fill in per-algorithm, per-ETF results in a consistent, tabular structure that makes cross-algorithm comparisons and aggregations straightforward.

The second line, olps_test.algo = olps_algos, attaches the actual algorithm objects (or references) to the table by creating a column named “algo” and populating it with olps_algos. Conceptually this ties each row label (an algorithm name) to the executable implementation we will use to generate the values for the other columns. If olps_algos is a list/array whose order matches algo_names, assignment will place each implementation on the corresponding row; if it’s a Series keyed by names, pandas will align by index — so explicit indexing is the safer choice to avoid accidental misalignment. Storing the algorithm objects in the DataFrame lets downstream code iterate rows, call .algo.run(…) or similar, and write results back into the same row, keeping names, implementations and outputs co-located.

A couple of practical notes: attribute-style assignment (olps_test.algo = …) is shorthand for olps_test[‘algo’] = …, but using the bracket form is slightly more robust (avoids subtle attribute collisions and is clearer to readers). Also be aware that putting algorithm objects into a DataFrame makes that column non-scalar and not directly CSV-friendly — if you need to persist identifiers rather than live objects, store a name or key instead and keep implementations in a separate mapping. Overall, this layout is chosen to support the primary goal — systematically running and comparing multiple OLPS algorithms across a diversified ETF set while keeping their implementations and results organized for easy analysis.

# run all algos

for name, alg in zip(olps_test.index, olps_test.algo):

olps_test.ix[name,’results’] = alg.run(test)olps_test in this context is acting as the registry of algorithms to evaluate: each row represents one OLPS algorithm (identified by the DataFrame index) and contains at least an ‘algo’ column that holds an algorithm object. The loop pairs each row label with its corresponding algorithm object using zip(olps_test.index, olps_test.algo), so the code processes every configured algorithm in turn and keeps the algorithm–row association explicit rather than relying on positional indexing.

For each algorithm, alg.run(test) is invoked. Conceptually this is the simulation/signal-generation call: the algorithm consumes the test dataset (the ETF price or return series for the evaluation period), iterates through time applying its portfolio update rules, and produces whatever result object the algorithm is designed to return — typically a time series of portfolio weights and/or P&L, plus whatever metrics or traces are needed for downstream comparison (cumulative returns, drawdowns, transaction costs, etc.). We run algorithms sequentially because these runs are stateful simulations that must execute their internal loop logic; they cannot be vectorized across algorithms in a simple way.

The result of each run is then stored back into the olps_test table under the ‘results’ column for the row keyed by the algorithm name: olps_test.ix[name,’results’] = alg.run(test). This keeps all outputs co-located with their configuration and metadata, which makes later aggregation, ranking, plotting, and reporting straightforward — you can iterate the DataFrame and pull each algorithm’s result object without needing a separate mapping structure. Using label-based assignment ensures the results map to the correct algorithm even if the DataFrame’s row order changes.

A few practical considerations behind this pattern: storing the full run output in the registry facilitates reproducible comparisons across a diversified set of ETFs because all run artifacts are retained with the algorithm definition; running each algorithm on the same immutable test input preserves comparability. Be aware that .ix is deprecated in recent pandas versions; prefer .loc[name, ‘results’] or .at[name, ‘results’] for label-based assignment. Also consider adding exception handling and timing around alg.run(test) if any algorithm can error or take disproportionately long — this keeps a long evaluation sweep robust and helps diagnose outliers. Finally, ensure alg.run does not mutate the shared test object (or pass a copy) so one algorithm’s internal side effects cannot contaminate another’s evaluation.

# Let’s make sure the fees are 0 at first

for k, r in olps_test.results.iteritems():

r.fee = 0.0This loop walks through the collection of experiment results held in olps_test.results and deliberately resets each result object’s fee attribute to 0.0. The immediate effect is to neutralize transaction or management costs stored on those result objects so that any downstream calculations (cumulative returns, turnover-adjusted performance, Sharpe-like metrics, etc.) reflect pure strategy behavior rather than being conflated with fee effects. Practically, this is an initial, deterministic normalization step: by zeroing fees up front you create a consistent baseline across all OLPS runs and ETF mixes, which makes it possible to compare algorithmic decisions (rebalancing frequency, weighting rules, response to market moves) on an even playing field.

Why we do this matters for interpretation. Fees can materially change performance rankings between algorithms because they penalize turnover and frequent trades; removing fees lets you assess the intrinsic quality of each OLPS policy without that confounding factor. This supports two common workflows: (1) establishing a fee-free benchmark to evaluate the pure signal and risk-return profile of each algorithm, and (2) later reintroducing realistic fee schedules to measure sensitivity and real-world robustness. A couple of operational notes: this mutates the existing result objects — so if you need to preserve original fee settings, make a copy before resetting — and ensure that no fees were already baked into precomputed metrics; otherwise you’ll need to recompute those metrics after the reset to avoid stale, inconsistent numbers.

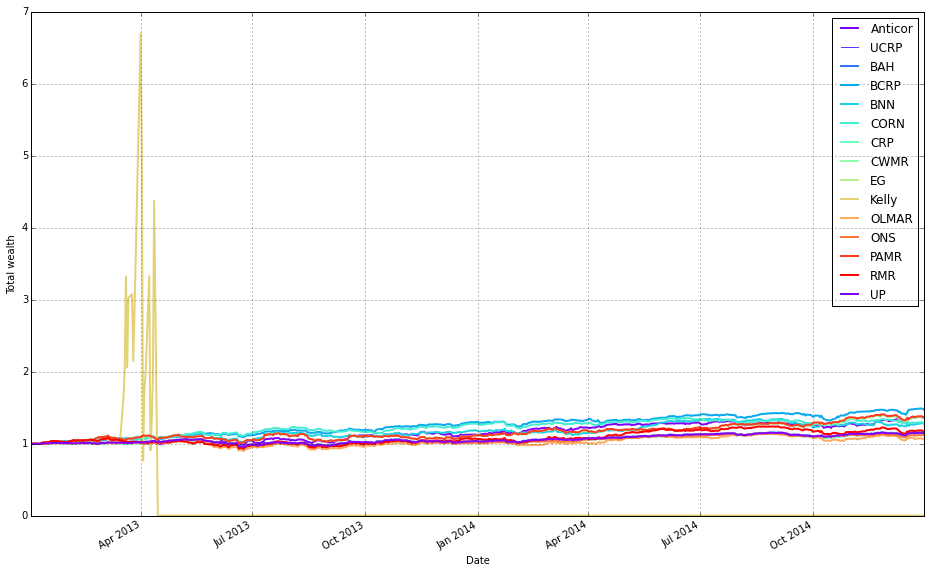

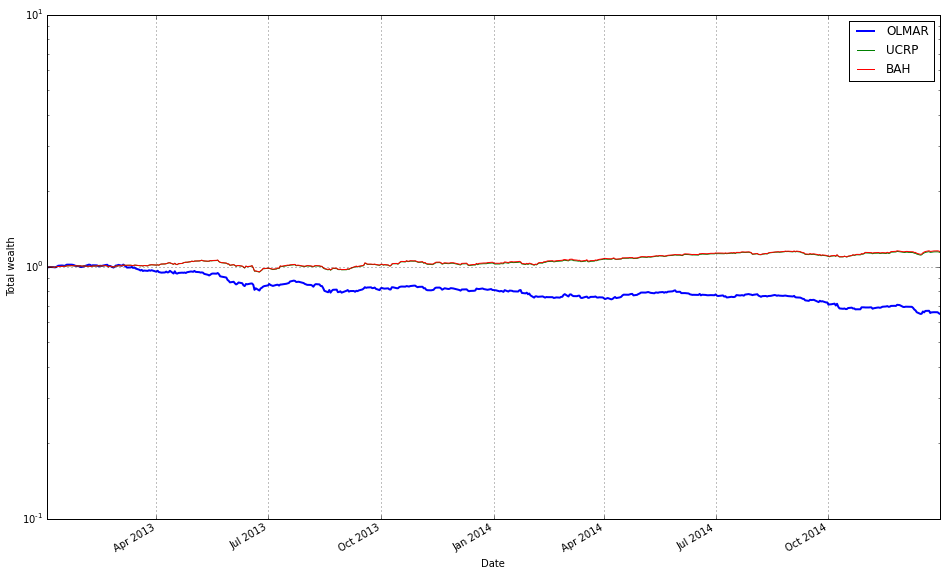

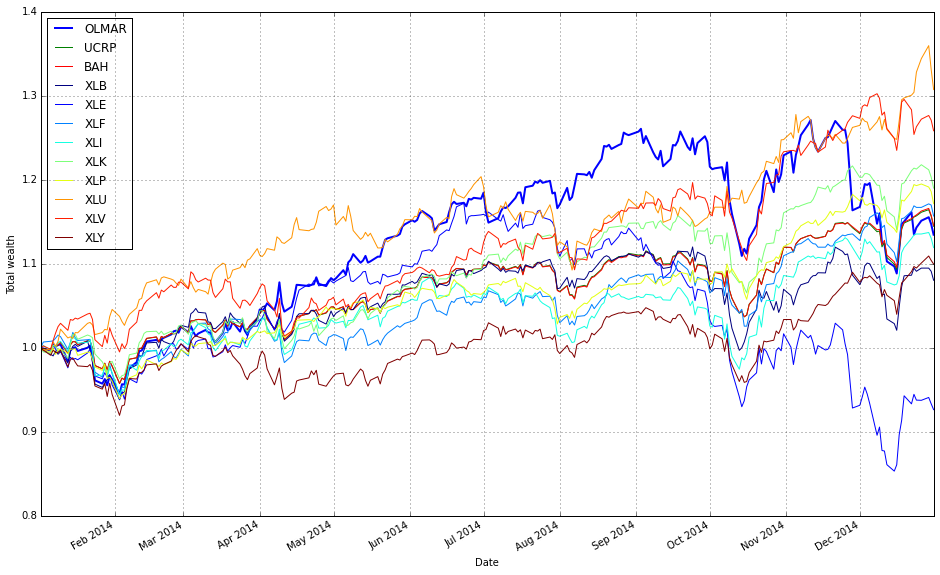

# plot as if we had no fees

# get the first result so we can grab the figure axes from the plot

ax = olps_test.results[0].plot(assets=False, weights=False, ucrp=True, portfolio_label=olps_test.index[0])

for k, r in olps_test.results.iteritems():

if k == olps_test.results.keys()[0]: # skip the first item because we have it already

continue

r.plot(assets=False, weights=False, ucrp=False, portfolio_label=k, ax=ax[0])This block builds a single comparative return chart for the set of OLPS runs so you can visually compare their performance (here, deliberately ignoring transaction fees). The code starts by taking the first result object out of olps_test.results and calling its plot method to create the figure and capture the axes. That first call sets up the visual context and also requests the ucrp series (u niform constant rebalanced portfolio) as a baseline by passing ucrp=True; assets and weights are suppressed so the plot stays focused on portfolio-level returns. The portfolio_label for that first curve is taken from the test collection’s index so the baseline/first algorithm line is named appropriately in the legend.

After the initial figure is created, the loop walks the entire results collection and re-plots each subsequent result onto the same axes so all return series share a single chart. The loop explicitly skips the first entry (since it was drawn already) and calls r.plot with ucrp=False for the rest to avoid redrawing the baseline multiple times; assets and weights remain False for the same reason (we only want the portfolio-return curves). Passing ax=ax[0] attaches each new line to the same subplot returned by the initial call — the plot API returns an array-like of axes, and ax[0] is the primary axis you want to overlay.

Conceptually, the decisions here are about clarity and fair comparison: draw only portfolio-level cumulative returns (no per-asset or weight diagnostics) so the chart is directly comparable across algorithms, include the UCRP baseline only once so it’s a stable benchmark, and reuse the same axes so visual alignment, scales, and legend work consistently. This produces a clean, side-by-side visual comparison of different OLPS strategies applied to the diversified ETF set, allowing you to see relative performance without conflating it with fee effects or extra subplot noise.

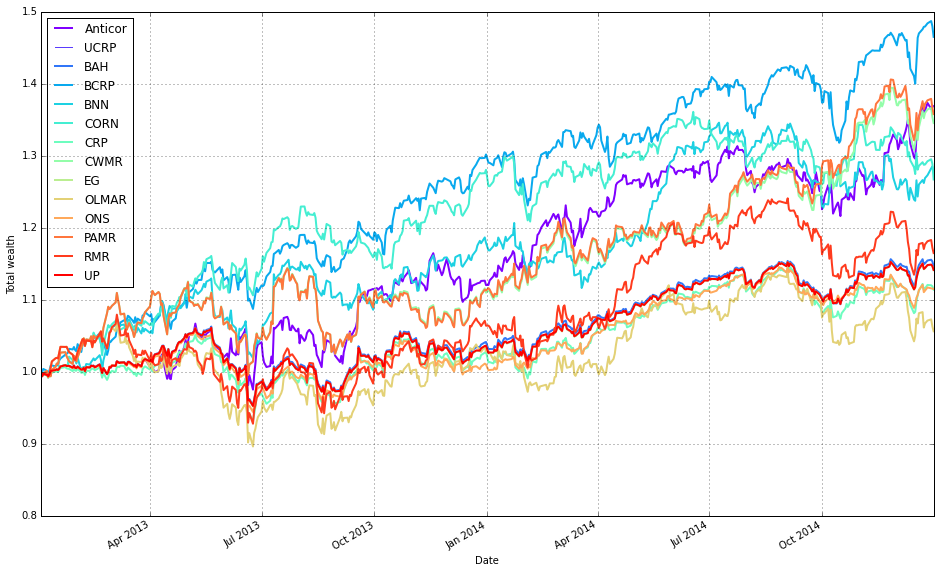

Remove Kelly from the mix after it went wild and crashed

# plot as if we had no fees

# get the first result so we can grab the figure axes from the plot

ax = olps_test.results[0].plot(assets=False, weights=False, ucrp=True, portfolio_label=olps_test.index[0])

for k, r in olps_test.results.iteritems():

if k == olps_test.results.keys()[0] or k == ‘Kelly’: # skip the first item because we have it already

continue

r.plot(assets=False, weights=False, ucrp=False, portfolio_label=k, ax=ax[0])This block builds a single comparison plot of portfolio-level performance for a suite of OLPS algorithms (on diversified ETFs) while intentionally omitting trading fees so you can see each strategy’s raw, pre-cost behavior. It starts by plotting the first result in olps_test.results with assets=False and weights=False so the plot shows only the portfolio-level time series (no per-asset or weight visualizations). The first call also sets ucrp=True, which draws the uniform constant-rebalanced-portfolio baseline on that axis; capturing the returned axes in ax lets us reuse the same figure/axis for subsequent overlays so every algorithm is plotted on the same coordinate system for direct comparison.

Next, the code loops over every result in olps_test.results and overlays each algorithm’s portfolio series onto the existing axis. For each item it skips two cases: the first entry (because it was already plotted) and the ‘Kelly’ entry (explicitly excluded here — presumably to avoid re-plotting a curve that’s been handled differently or to reduce visual clutter; you should confirm the intent with whoever wrote the test). For every algorithm that is plotted in the loop it calls r.plot with assets=False and weights=False (again focusing on the portfolio curve), ucrp=False (so the UCRP baseline — already drawn by the first plot — is not redundantly re-rendered), and portfolio_label=k so each overlaid line appears with a clear legend entry. Passing ax=ax[0] ensures the overlay happens on the same primary axis returned by the initial plot call.

In short: the first result establishes the figure and draws the UCRP baseline; the loop overlays the remaining algorithms’ portfolio returns on that same axis (excluding duplicates and the explicitly omitted ‘Kelly’), producing a clean, directly comparable visualization of the algorithms’ pre-fee performance. Small robustness notes: capture the first key once (rather than re-indexing keys() repeatedly) or use next(iter(…)) for clarity, and double-check why ‘Kelly’ is skipped so the omission is intentional.

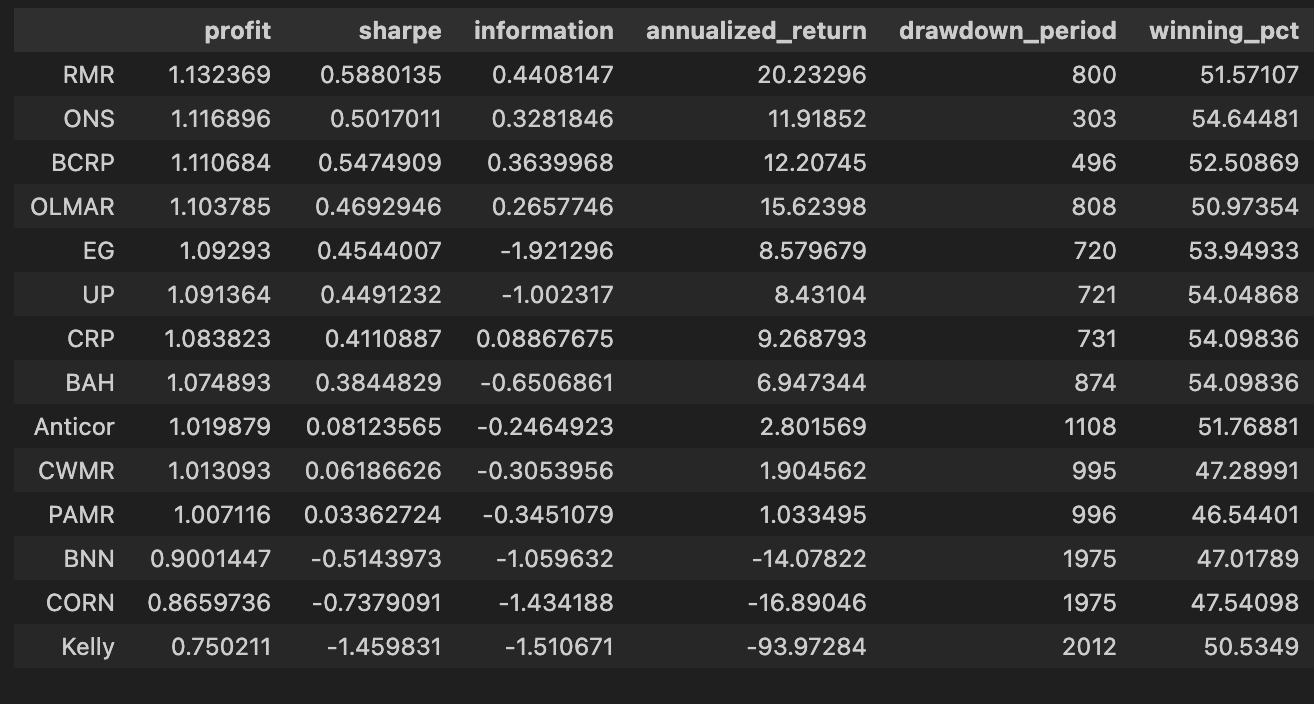

olps_stats(olps_test)

olps_test[metrics].sort(’profit’, ascending=False)First we call olps_stats(olps_test). Conceptually this is the function that takes the raw per-algorithm test outputs (weights over time, per-period returns, trades/turnover, etc.) and reduces them to a compact set of performance metrics that make algorithms comparable. Practically it walks through each algorithm’s time series, computes cumulative profit/wealth and standard performance summaries (annualized return and volatility, Sharpe or other risk-adjusted ratios, maximum drawdown, total turnover and transaction cost-adjusted profit, win rate, maybe per-period statistics), and writes those summaries back into the olps_test structure (or returns a metrics table attached to it). We do this summarization because the raw time-series are hard to compare at a glance; the metrics make it possible to rank and filter algorithms on concrete criteria and to check that differences are not just noise but reflect meaningful tradeoffs (e.g., higher profit achieved at the cost of much higher drawdown or turnover).

Immediately after we select the metrics table from olps_test and sort it by the profit column in descending order. This step is the simple ranking step: place the highest cumulative profit algorithms at the top so you can quickly see which OLPS strategies produced the largest nominal gains on the ETF set. Two practical points to be aware of here: (1) sorting by raw profit is a useful first pass but can be misleading if you ignore risk and costs — high profit can be achieved with unacceptable volatility or drawdown, so follow-up inspection of Sharpe, drawdown and turnover is important; (2) depending on the data structure and environment, the sort call may return a new sorted view rather than mutating olps_test in place (so if you need to keep the sorted order programmatically, assign the result or use an in-place sort variant). In short: olps_stats creates the comparable performance summaries, and the subsequent sort ranks the algorithms by nominal profit so you can spot top performers quickly, after which you should validate those leaders on risk-adjusted and transaction-cost-aware metrics.

Focus: OLMAR

Rather than using the default settings, we will test several values of the `window` parameter to determine whether OLMAR’s performance can be improved.

# we need need fewer colors so let’s reset the colors_cycle

mpl.rcParams[’axes.color_cycle’]= default_color_cycleThis single line changes Matplotlib’s global color sequence so that every subsequent plot call on an axes will draw lines using the colors in default_color_cycle rather than whatever color sequence Matplotlib would otherwise use. In terms of the plotting “story,” we set this right before generating the visual comparisons of OLPS algorithms across ETFs so that each algorithm’s time series (cumulative returns, weights, etc.) is drawn from a controlled, smaller palette. The practical reason for doing this is readability and consistency: with a reduced, well-chosen color cycle you avoid visually noisy plots, ensure legends remain clear, and make it easier to map the same algorithm to the same color across multiple subplots or figures — all important when the goal is to compare many algorithms across a diversified set of ETFs.

Mechanically, Matplotlib consults rcParams as global styling state; setting the axes color cycle tells the axes to hand out colors from that list in order for each plotted line. That’s why we “reset” it here — we want deterministic, human-friendly colors for the comparisons rather than letting Matplotlib pick or continue an overly long or inconsistent sequence. Be aware this is a global change (it affects all subsequent plotting in the process), so if you need isolated style changes for a single figure it’s safer to use a context manager or set colors per plot explicitly.

One operational note: the key used here (axes.color_cycle) is the older API; in modern Matplotlib versions the canonical approach is to set axes.prop_cycle (using cycler) or to explicitly map algorithm names to colors. Using prop_cycle or an explicit mapping is more future-proof and lets you guarantee the same color assignment even when the number of algorithms exceeds the palette size. Overall, this line is about controlling visual encoding so that algorithm comparisons across ETFs are clear, consistent, and reproducible.

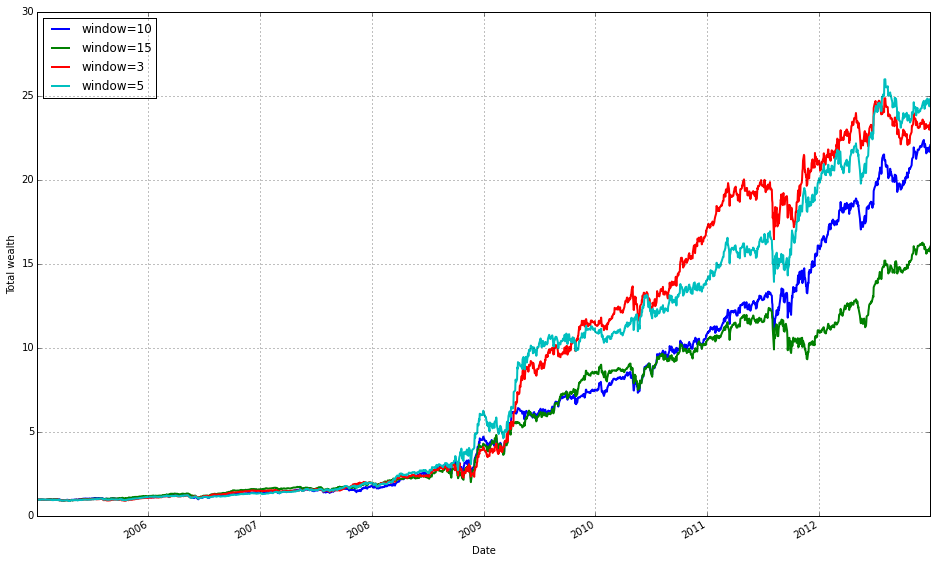

train_olmar = algos.OLMAR.run_combination(train, window=[3,5,10,15], eps=10)

train_olmar.plot()This block instantiates and runs a small ensemble of OLMAR (On-Line Moving Average Reversion) experts over your training data, then draws a diagnostic plot of the result. Under the hood run_combination creates separate OLMAR strategies for each moving-average window you supplied (here 3, 5, 10 and 15 periods). At each step in time every expert computes a short-term prediction by comparing a simple moving average (over its window) to the current prices: assets whose current price is below their moving average are treated as likely to revert upward, so those assets receive relatively more weight; assets above their moving average are treated as likely to fall and receive less weight. Each OLMAR expert then checks the expected portfolio return (the inner product of its current portfolio and its prediction vector) against the target threshold eps. If the expected return is already above eps the expert leaves its allocation unchanged; if it is below eps the expert performs the OLMAR update, which minimally perturbs the current allocation (via a quadratic projection onto the simplex) so that the expected return meets the threshold while preserving the budget and nonnegativity constraints. This update logic is what enforces mean-reversion trading while avoiding aggressive, unstable moves.

run_combination then aggregates the behavior of those experts into a single meta-portfolio over time. Rather than choosing one window a priori, the combination routine weights the experts (typically using their recent performance or another online weighting scheme) so the meta-portfolio emphasizes horizons that have been working recently and dampens those that have not. That ensemble step is the reason you pass multiple window lengths: different ETFs and market regimes revert on different time scales, so parallel experts across short and medium windows give robustness to the overall strategy and reduce the risk of committing to a single, misspecified horizon.

The eps hyperparameter controls the aggressiveness of each expert’s update: a larger eps forces the algorithm to demand a higher predicted return before it accepts the current allocation, which results in more frequent or larger corrections toward the mean-reversion target; a smaller eps makes the expert more tolerant and leads to gentler updates. In practical terms you tune eps and the window set to trade off responsiveness (capturing short-lived reversions) against stability (avoiding excessive turnover and overfitting).

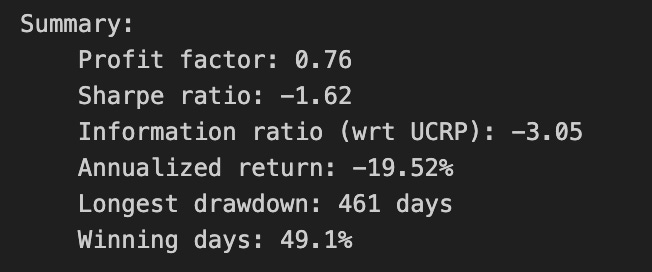

Finally, train_olmar.plot() simply visualizes the outcome of the combined OLMAR run on your training set — typically cumulative wealth over time and, depending on the implementation, diagnostics like expert weights or turnover. You run this during the training phase to inspect how the ensemble performed across your diversified ETF universe, to verify that different windows contribute as expected, and to decide which OLPS variants or hyperparameters you want to carry forward into the comparative evaluation.

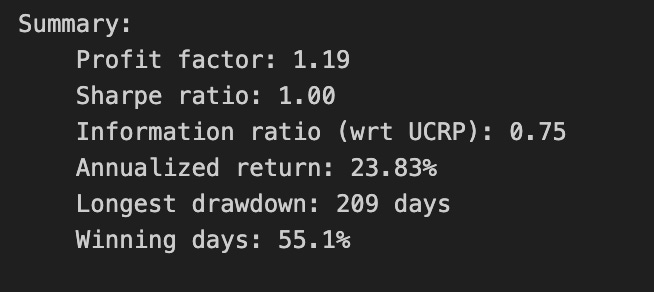

print(train_olmar.summary())Calling print(train_olmar.summary()) hands control to the train_olmar object’s summary routine and emits a compact, human‑readable report of the OLMAR backtest you just ran. Under the hood the summary aggregates the time series that the backtest produced — per‑period portfolio returns, portfolio weight vectors, realized transaction costs and any benchmark returns — and reduces them to a set of standard performance and risk statistics (cumulative and annualized return, volatility, Sharpe or other risk‑adjusted ratios, maximum drawdown, turnover, and often gross vs net returns). It will also usually show the key algorithm hyperparameters that produced those results (for OLMAR, things like the moving‑average window and epsilon/target parameters), so you can link performance back to configuration choices.

Why we call this here: the summary is the quick diagnostic that lets us compare OLMAR’s behavior to other OLPS algorithms across the same diversified ETF universe. The summary’s annualized and cumulative metrics tell you whether the method produced excess return; volatility and Sharpe expose risk‑adjusted performance; max drawdown highlights tail risk and capital preservation; turnover and net returns reveal how much trading frictions and transaction costs erode theoretical gains. Because OLMAR is a mean‑reversion/moving‑average based strategy, high turnover or concentrated allocations in the summary can indicate that the algorithm is repeatedly switching bets to chase short‑term reversions, which will be costly in a universe of ETFs with nontrivial spreads and fees.

How those numbers are typically computed is important to keep in mind when you interpret the printout: per‑period portfolio returns come from dotting realized price relatives with the weight vectors, cumulative return compounds those per‑period returns, volatility is the standard deviation of period returns scaled to an annual basis, Sharpe uses an assumed risk‑free rate to convert that to a risk‑adjusted metric, and max drawdown is computed from the running peak of the equity curve. Turnover is derived from the L1 distance between successive weight vectors (often normalized) and combined with the per‑trade cost model to produce net returns. Because the summary consolidates all this into single numbers, it’s a deliberate trade‑off between quick comparability and loss of temporal detail.

Practical next steps after reading the summary: use it to rank OLMAR against other OLPS methods on the same ETFs, but don’t stop there — inspect the time‑series returns, weight trajectories, and drawdown periods to understand when and why OLMAR succeeded or failed. Verify the backtest assumptions embedded in the summary (frequency, transaction cost model, rebalancing rules, look‑ahead protection) and run sensitivity checks on OLMAR’s hyperparameters if the summary suggests either strong promise or unacceptable risk/turnover. The summary is your starting point for model comparison and hypothesis testing, not the final verdict.

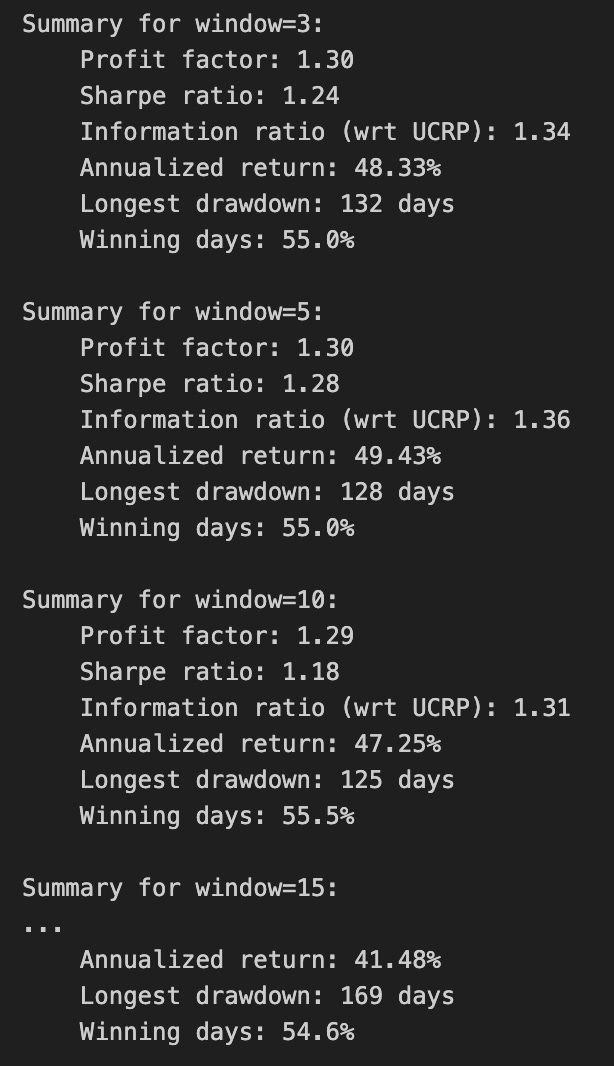

train_olmar = algos.OLMAR.run_combination(train, window=5, eps=[3,5,10,15])

train_olmar.plot()We’re running a small ensemble of OLMAR (On-Line Moving Average Reversion) strategies on the training set and then visualizing the resulting performance. When train_olmar = algos.OLMAR.run_combination(train, window=5, eps=[3,5,10,15]) executes, the library spins up several OLMAR instances — one per epsilon value — all using a 5-period moving average as their prediction engine. At each time step, each OLMAR variant computes a predicted price-relative vector from the last 5 observations (the moving-average forecast), evaluates the expected return of its current portfolio against that prediction, and decides whether to rebalance. The core decision inside each variant is governed by the constraint b · x_pred >= eps: if the current portfolio’s predicted return falls below the chosen eps threshold, OLMAR computes a corrective update (a projection step that respects the long-only simplex constraint) whose magnitude is proportional to how far the predicted return is from the threshold. This projection keeps weights non-negative and summing to one, preventing invalid or excessively leveraged portfolios.

The reason we run a combination of epsilons rather than a single OLMAR is robustness to the sensitivity of that hyperparameter. Epsilon controls aggressiveness: smaller values make the strategy more conservative (fewer or smaller adjustments), while larger values force bigger updates and higher turnover in pursuit of larger predicted gains. By running eps = [3,5,10,15] we span a range of mean-reversion intensities so the ensemble can capture different reversion speeds that might exist across the diversified ETF set or across market regimes. The ensemble aggregation implemented by run_combination blends the signals from these differently tuned OLMARs into one meta-portfolio, reducing the risk of relying on one mis-specified epsilon and smoothing parameter-selection noise.

Using window=5 is a deliberate business-level choice: it encodes a weekly mean-reversion horizon for ETFs (five daily observations) so the predictor reacts to short-term reversions while still smoothing daily noise. Practically, shorter windows increase responsiveness but can overfit noise; longer windows are smoother but slower to react. The combination of multiple epsilons with this window gives us a way to explore responsiveness vs. aggressiveness trade-offs without repeatedly re-running separate experiments.

Finally, train_olmar.plot() gives you an immediate visual check of what happened on the training period — typically an equity curve (cumulative wealth) and often supplementary diagnostics like per-strategy contributions or turnover depending on the plotting implementation. Use that plot to validate whether the ensemble produced stable, monotonic gains or if it exhibits large drawdowns or high turnover; those signs tell you whether to adjust eps/window, add transaction-cost modeling, or compare against other OLPS algorithms in the same experimental framework.

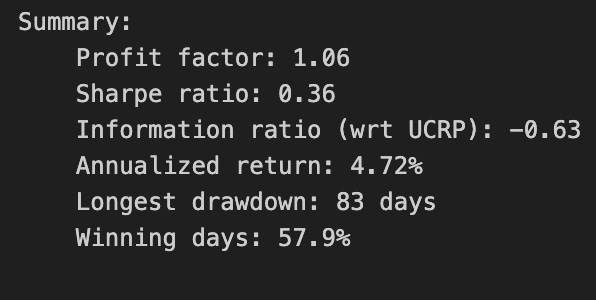

print(train_olmar.summary())Here you’re asking the trained OLMAR run to produce a compact, human-readable report of its backtest and then emitting that report to the console. The train_olmar object holds the time-series output and internal state produced by running the OLMAR online-portfolio-selection routine over the ETF training window (wealth evolution, per-period portfolio vectors, realized returns, and any bookkeeping about trades and transaction costs). Calling its summary() method collapses those raw time-series into the key diagnostics you need to compare algorithms: overall cumulative (final) wealth, annualized or geometric mean return, volatility or standard deviation of returns, risk-adjusted ratios such as Sharpe (and sometimes Sortino), maximum drawdown and its timing, hit-rate or percentage of positive periods, and measures of activity like turnover and total transaction cost. The summary may also expose final or average portfolio weights so you can verify whether OLMAR produced a diversified allocation or concentrated bets.

We do this because raw returns curves are hard to compare across many algorithms and ETF universes; summary statistics distill performance into comparable signals and highlight trade-offs that matter operationally. For example, a high cumulative return with very high turnover signals that transaction costs or liquidity could erode out-of-sample performance on ETFs, whereas a modest return with low volatility and low drawdown might be preferable for a production allocation. The summary is also useful for debugging: extreme drawdowns, implausibly high final weights, or unexpectedly large turnover point to parameter issues (e.g., mean-reversion window, step-size) or data problems (lookahead, missing prices).

Finally, printing the summary is a quick, immediate step in the comparison workflow: you read these standardized metrics for OLMAR, then do the same for other OLPS algorithms and baselines (uniform buy-and-hold, market index). For reproducibility and deeper analysis, capture the summary output (or the underlying data) to files or structured logs so you can aggregate results, compute statistical significance, and inspect per-period behavior where the summary flags potential concerns.

We find that a window of 5 and eps of 5 are optimal over the training period; however, the default values (w=5, eps=10) were also acceptable for our purposes.

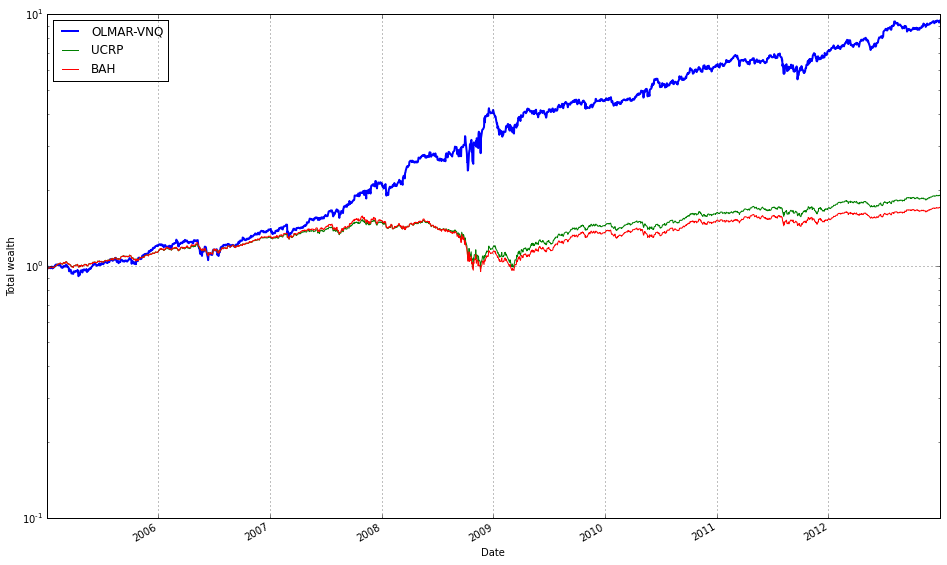

# OLMAR vs UCRP

best_olmar = train_olmar[1]

ax1 = best_olmar.plot(ucrp=True, bah=True, weights=False, assets=False, portfolio_label=’OLMAR’)

olps_train.loc[’CRP’].results.plot(ucrp=False, bah=False, weights=False, assets=False, ax=ax1[0], portfolio_label=’CRP’)This snippet picks the best-trained instance of OLMAR and draws a focused performance comparison against a constant-rebalanced baseline. The first line, best_olmar = train_olmar[1], selects the second element of a collection of trained OLMAR runs (presumably the one identified as “best” by prior evaluation); conceptually we’re saying “take the representative OLMAR model we want to inspect.” Next we call its plotting helper with ucrp=True and bah=True so the plot will include the two common baselines used in online portfolio selection: UCRP (uniform constant rebalanced portfolio) and BAH (buy-and-hold). Those baseline traces are included here because they provide simple, interpretable reference points for whether the adaptive OLMAR strategy actually adds value over fixed allocation strategies on the ETF universe.

The call also sets weights=False and assets=False to suppress allocation and per-asset traces; that choice intentionally narrows the visualization to portfolio-level performance (cumulative wealth or returns) rather than the distracting detail of how weights evolve. The portfolio_label=’OLMAR’ argument gives the main trace a clear legend name. The plot method returns axes (ax1) and the code immediately uses ax1[0] when overlaying the CRP result, which means we’re plotting the CRP line onto the same subplot produced for OLMAR. Passing ax=ax1[0] ensures the CRP trace shares the same axes/scales so the comparison is a direct, visual one.

Finally, olps_train.loc[‘CRP’].results.plot(…, portfolio_label=’CRP’) pulls the stored CRP result from the training summary and draws it without repeating the ucrp or bah baselines (ucrp=False, bah=False) to avoid duplicate baseline lines in the legend. In short, the snippet builds a concise, apples‑to‑apples plot: the best OLMAR run versus a constant-rebalanced baseline (and optionally BAH/UCRP) with allocation details hidden so you can quickly judge whether OLMAR improves cumulative performance on the diversified ETF set. A small implementation note: the code assumes the plot method returns a sequence of axes and that ax1[0] is the correct target axis — if the plotting API ever changes to return a single axis object you’ll need to adjust that indexing.

OLMAR outperforms CRP on the training set

# let’s print the stats