QuantScope — Algorithmic High-Frequency Trading System

QuantScope is a sophisticated high-frequency algorithmic trading module that uses machine learning (Q-learning) to self-regulate and self-optimize for maximum return in forex trading.

Download entire source code using the link at the bottom of article. Entire code with dataset.

Key Characteristics

Technology: Python-based reinforcement learning system

Trading Pair: CAD/USD (Canadian Dollar / US Dollar)

Machine Learning: Q-learning algorithm for decision making

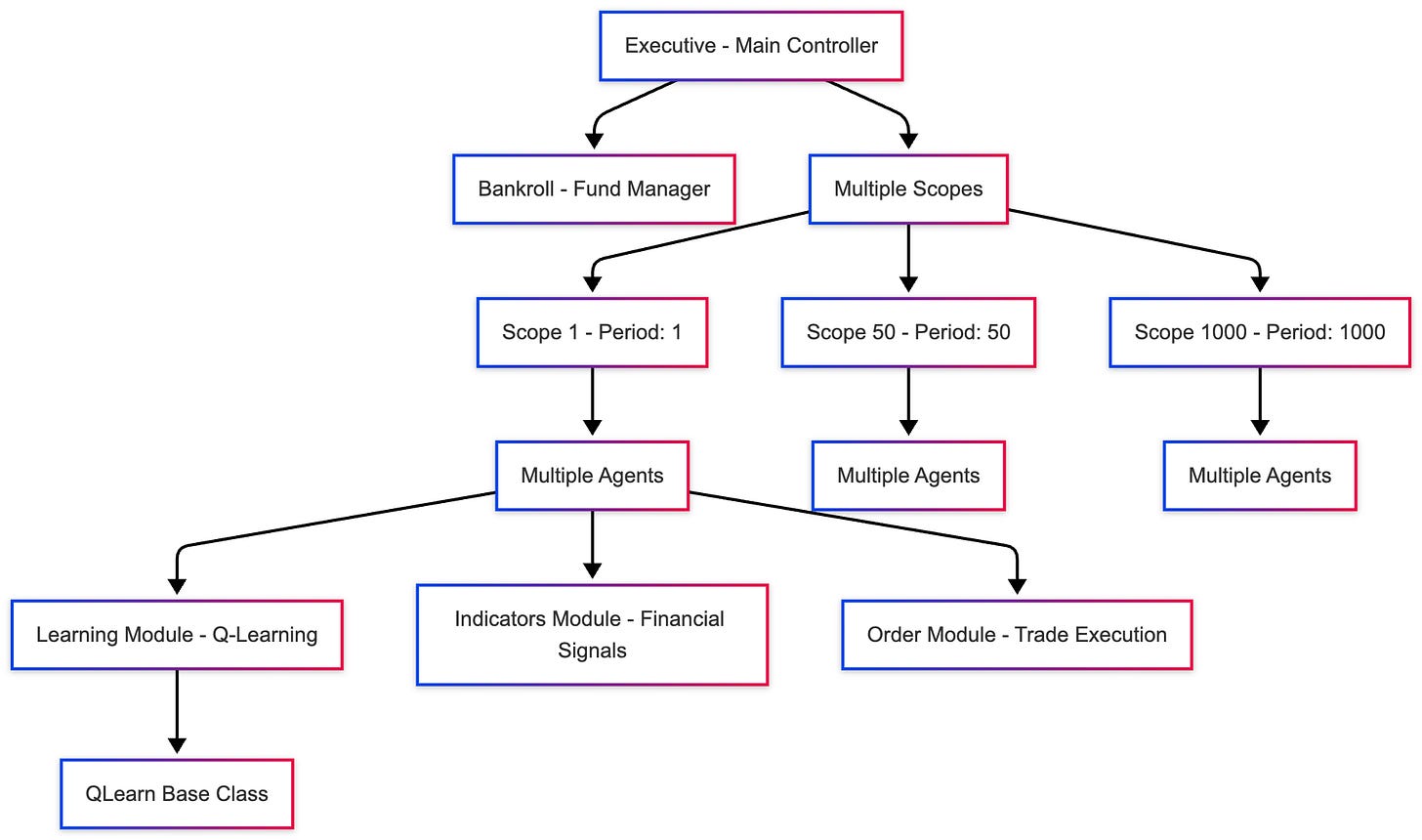

Architecture: Multi-agent system with scope-based trading

Core Concept: Scopes

The system uses an innovative concept called Scopes, which represents different time resolutions for analyzing market data.

What is a Scope? A sampling of time series quotes to discover trends along different time intervals

Purpose: At every moment, the system ensures at least one Agent per scope is looking for profitable trading opportunities

Default Scopes:

{1, 50, 1000}- meaning the system operates at three different time scales simultaneously

This multi-resolution approach allows the system to capture both short-term fluctuations and long-term trends.

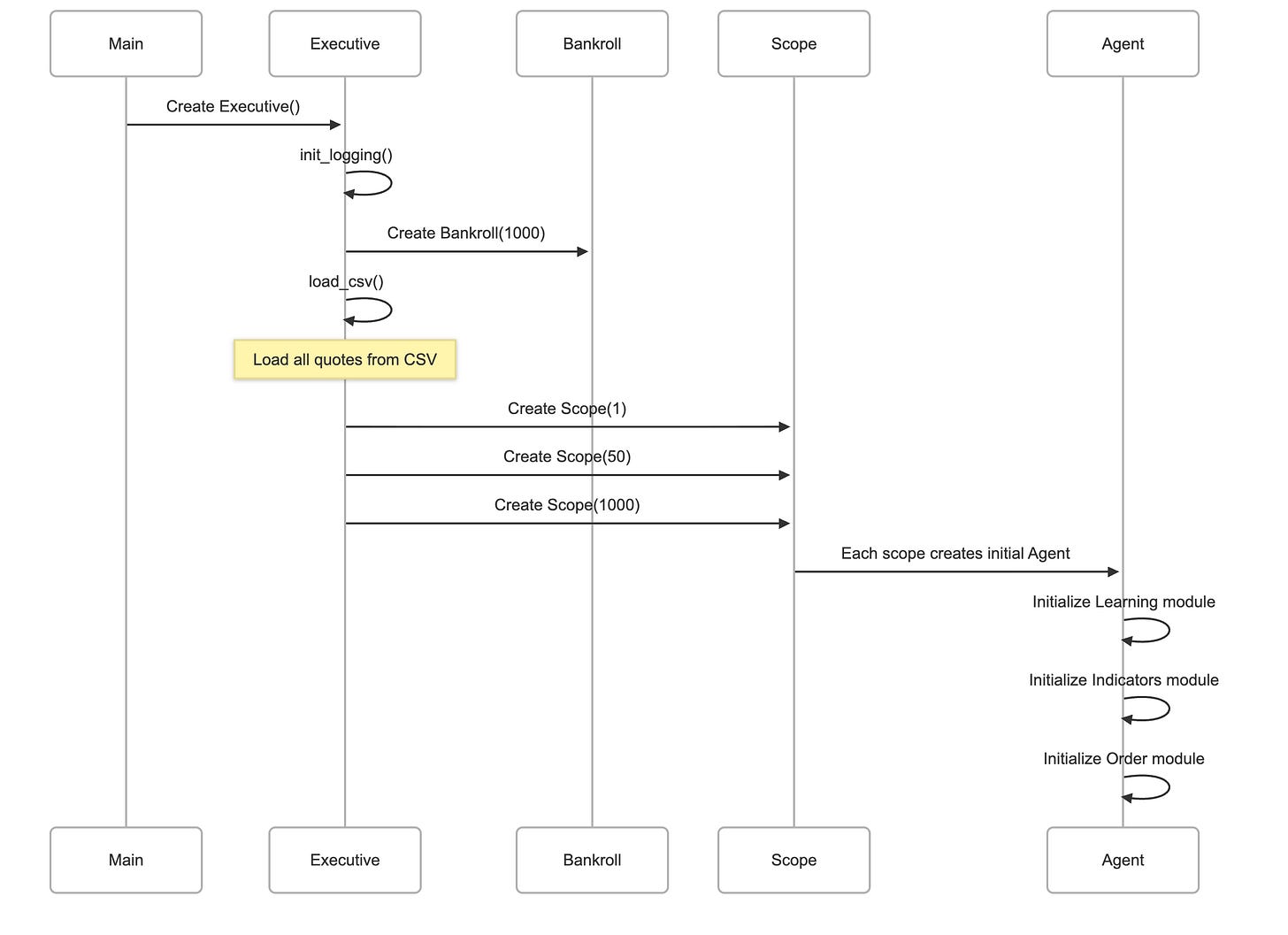

System Architecture

Trading Loop (One “Hop”)

Individual Files

bankroll.py

Bankroll Module

The Bankroll module serves as the financial bookkeeping heart of the QuantScope trading system. This elegant yet powerful class manages all monetary transactions, maintains the current fund balance, and provides comprehensive logging of every financial operation that occurs during the trading simulation. Think of it as the central bank vault that meticulously tracks every dollar that flows in and out of the trading system, ensuring complete transparency and accountability for all trading activities.

The Bankroll class is instantiated once at the beginning of the trading simulation with an initial capital allocation. From that moment forward, it becomes the single source of truth for the system’s financial state. Every agent that wishes to open a position must deduct funds from the Bankroll, and every closed position that yields profit or loss must report back to the Bankroll. This centralized approach ensures that the system never loses track of its financial position and can immediately detect if trading activities have depleted the available capital.

Class Definition and Purpose

The Bankroll class encapsulates all fund management logic within a self-contained unit. It maintains three critical pieces of state: the current bankroll amount representing available capital, a transaction counter that assigns unique identifiers to each financial operation, and a dedicated logger that records every transaction to a separate log file for real-time monitoring and post-simulation analysis.

What makes this module particularly valuable is its dual-purpose design. Not only does it serve as a passive record-keeper, but it also acts as an active safety mechanism. By raising an exception when the bankroll goes negative, it immediately halts trading operations if the system runs out of money, preventing the simulation from continuing with invalid negative capital that would distort learning and analysis.

Constructor Method

def __init__(self, vault, funds):

self.init_logging(vault)

self.bankroll = funds

self.transactions = 0

self.logger.info(’Bankroll initialized with $ {}’.format(funds))The constructor method initializes a new Bankroll instance and sets up the foundational infrastructure for fund management. When called, it accepts two parameters: the vault parameter specifies the file path where transaction logs should be written, while the funds parameter establishes the starting capital for the trading simulation.

The first action taken by the constructor is to invoke the `init_logging` method, passing the vault file path. This critical step establishes the logging infrastructure before any financial operations can occur, ensuring that even the initialization event itself can be recorded. Once logging is configured, the method stores the initial funds in the `self.bankroll` instance variable, which will be modified throughout the simulation as trading profits and losses accumulate.

The transaction counter `self.transactions` begins at zero, ready to be incremented with each financial operation. Finally, the constructor logs an informational message announcing the initialization and documenting the starting capital amount. This creates an auditable record showing exactly how much money the system began trading with, which becomes crucial when analyzing final performance metrics.

Transaction Method

def transaction(self, val):

self.bankroll += val

self.transactions += 1

self.logger.info(’Transaction {id}: $ {val} added to bankroll: $ {br}’\

.format(id=self.transactions, val=val, br=self.bankroll))

if self.bankroll < 0:

raise Exception(’We ran out of money’)The transaction method represents the core operational function of the Bankroll class, handling every monetary movement that occurs during trading. This method is called whenever an agent opens or closes a position, with the val parameter carrying either a negative value when funds are being spent to open a position, or a positive value when proceeds from closing a position are being returned.

When invoked, the method first updates the bankroll by adding the transaction value. For opening positions, this represents a deduction since the value is negative, reducing available capital by the amount needed to purchase the currency position. For closing positions, this adds the proceeds back to the available funds, which may be more or less than what was originally spent depending on whether the trade was profitable.

Immediately after updating the balance, the method increments the transaction counter. This serves multiple purposes: it provides a unique identifier for each transaction making it easier to trace specific operations in the logs, it allows the system to calculate the total number of trades executed, and it helps correlate transactions with agent activities when analyzing system behavior.

The logging statement that follows creates a detailed record of the transaction. It captures the transaction ID, the amount added or subtracted (which could be negative), and the resulting bankroll balance after the transaction completes. This three-part record allows someone monitoring the `bankroll.log` file to see the complete story of each financial operation: which transaction number it was, how much money moved, and what the new total balance became. The format string clearly shows these relationships, making the log file human-readable for real-time monitoring.

The final component of this method implements a critical safety mechanism. After every transaction, the code checks whether the bankroll has fallen below zero. If this condition is detected, meaning the system has attempted to trade with more money than it possesses, the method immediately raises an exception with the message “We ran out of money.” This exception propagates up through the call stack and halts the entire simulation, preventing the system from continuing to operate in an invalid financial state. This safeguard ensures that the Q-learning algorithm never learns from scenarios where the agent traded with capital it didn’t actually have, which would corrupt the learning process and invalidate the simulation results.

Get Bankroll Method

```python

def get_bankroll(self):

return self.bankroll

```The `get_bankroll` method provides a simple but essential accessor function that allows other components of the system to query the current financial state without directly accessing the internal `self.bankroll` variable. While this method appears trivial at first glance, consisting of just a single return statement, it embodies an important principle of object-oriented design: encapsulation.

By providing this dedicated method for reading the bankroll value, the class maintains control over how its internal state is accessed. Other system components, particularly the Executive class that needs to report the current bankroll in its logging statements, call this method to retrieve the current balance. This approach allows the Bankroll class to potentially add additional logic in the future, such as calculating interest, applying fees, or adjusting for currency conversions, without requiring changes to any code that reads the bankroll value.

The method is called frequently during the simulation’s main loop. At the beginning of each “hop” (the system’s term for a single step through the historical quote data), the Executive calls `get_bankroll()` to include the current financial state in its status logging. This creates a historical record of how the bankroll evolves over time, making it easy to visualize the system’s profitability trajectory and identify periods of strong or weak performance.

Logging Initialization Method

```python

def init_logging(self, log_file):

self.logger = logging.getLogger(’bankroll’)

self.logger.setLevel(logging.INFO)

fh = logging.FileHandler(log_file, mode=’w’)

fh.setLevel(logging.INFO)

ch = logging.StreamHandler()

ch.setLevel(logging.ERROR)

formatter = logging.Formatter(’%(asctime)s - %(name)s - %(levelname)s ‘\

‘- %(message)s’)

fh.setFormatter(formatter)

ch.setFormatter(formatter)

self.logger.addHandler(fh)

self.logger.addHandler(ch)

```The `init_logging` method establishes the sophisticated logging infrastructure that makes the Bankroll’s operations transparent and auditable. This method is called exclusively by the constructor and sets up a dual-output logging system that writes to both a file and the console, though with different filtering levels for each destination.

The method begins by creating a named logger instance using Python’s logging framework, specifically requesting a logger with the name ‘bankroll’. This naming is significant because it allows the logging system to distinguish Bankroll transactions from other system logs, and it enables different configuration for this specific logger compared to others in the application. The logger’s base level is set to INFO, meaning it will process any message at INFO level or higher severity.

Next, the method creates a FileHandler pointing to the log file path provided in the log_file parameter. This handler is configured to open the file in write mode (‘w’), which means each time the simulation runs, it starts with a fresh log file, overwriting any previous results. The file handler’s level is set to INFO, ensuring that all informational messages about transactions and initialization will be written to the file. This creates the detailed transaction record that users can monitor in real-time using the `tail -f` command.

The method then establishes a second output channel: a StreamHandler that writes to the console (standard error stream). Interestingly, this handler’s level is set to ERROR rather than INFO. This design choice means that normal transaction operations won’t clutter the console output, but if something goes seriously wrong — such as the bankroll going negative — those critical error messages will appear on the console where they’re immediately visible to anyone running the simulation.

A unified formatter is created and applied to both handlers. This formatter specifies that each log entry should include the timestamp of when the event occurred, the name of the logger (‘bankroll’), the severity level of the message (INFO, ERROR, etc.), and finally the actual message content. This standardized format makes it easy to parse log files programmatically or scan them visually, as every entry follows the same predictable structure.

Finally, both handlers are attached to the logger instance. From this point forward, whenever code calls `self.logger.info()` or other logging methods, the message flows through this configured logger and gets written to both destinations according to their respective filtering levels. This dual-stream approach provides both a permanent detailed record (the file) and immediate visibility of critical issues (the console), making the system both observable during execution and analyzable after completion.

Role in the Trading System

The Bankroll module operates as the financial foundation upon which the entire QuantScope trading system is built. When the Executive class initializes the simulation, one of its first actions is to create a Bankroll instance with the configured starting capital, typically one thousand dollars. This Bankroll object is then passed as a reference to every Scope that gets created, and subsequently to every Agent that gets spawned within those scopes.

This shared reference pattern means that all agents across all scopes are accessing and modifying the same single Bankroll instance. When an agent in Scope 1 opens a buy position, it calls the Bankroll’s transaction method with a negative value representing the cost of the purchase. Microseconds later, an agent in Scope 50 might close a sell position and call the same Bankroll’s transaction method with a positive value representing the proceeds. Both operations modify the same underlying balance, maintaining a single source of truth for the system’s financial state.

The real-time logging capability of the Bankroll makes the trading system remarkably transparent. Users can open a terminal window, run the `tail -f logs/bankroll.log` command, and watch money flow in and out as the simulation progresses. Each line in this log represents an actual trading decision made by a learning agent, the financial consequences of that decision, and the cumulative effect on the system’s wealth. This visibility is invaluable for understanding how the Q-learning algorithm is performing and whether the agents are successfully learning profitable trading strategies.

The safety mechanism that halts execution when funds are depleted serves a dual purpose. On one level, it prevents the simulation from continuing with nonsensical negative capital, which would make the results meaningless. On another level, it provides immediate feedback about the algorithm’s effectiveness. If the simulation consistently runs out of money early in the process, it indicates that the agents are making poor trading decisions and the Q-learning parameters may need adjustment. Conversely, if the simulation completes with a healthy positive bankroll, it demonstrates that the agents successfully learned to trade profitably within the constraints of the historical data.

The transaction counter maintained by the Bankroll also provides valuable metrics. At the end of a simulation run, the total number of transactions indicates how actively the system traded. Combined with the final bankroll amount, this allows calculation of average profit per trade, which helps evaluate the quality of the learning algorithm’s decisions beyond just the final capital amount.

Executive Module

Overview

The Executive module serves as the master orchestrator and supreme commander of the entire QuantScope algorithmic trading system. This class sits at the apex of the system’s hierarchy, wielding complete control over the simulation lifecycle from initialization through execution to completion. The Executive is responsible for loading historical market data, establishing the financial infrastructure, creating and managing multiple trading scopes, and conducting the primary trading loop that drives the entire simulation forward through time.

When you run QuantScope by executing python python/executive.py, the Executive class springs into action as the entry point of the application. It coordinates the complex interplay between data loading, scope initialization, agent creation, and the continuous flow of market quotes through the system. Think of the Executive as a symphony conductor who doesn’t play any instrument directly but ensures that all musicians (in this case, scopes and agents) receive their cues at precisely the right moments and perform in perfect harmony to create profitable trading strategies.

The design philosophy of the Executive embodies the principle of centralized control with distributed execution. While the Executive maintains tight control over the simulation’s overall flow and timing, it delegates the actual trading decisions to autonomous agents operating within their respective scopes. This separation of concerns creates a clean architecture where strategic oversight remains distinct from tactical trading operations.

Module Constants and Configuration

QUOTES_CSV = ‘data/DAT_NT_USDCAD_T_LAST_201601.csv’

LOG_FILE = ‘logs/runlog.log’

VAULT = ‘logs/bankroll.log’

FUNDS = 1000

SCOPES = {1, 50, 1000}

Q = dict()

ALPHA = 0.7

REWARD = tuple()

DISCOUNT = 0.314

LIMIT = 11Before the Executive class itself is even defined, the module establishes a collection of configuration constants that govern the simulation’s behavior. These constants represent the fundamental parameters that determine how the trading system operates, and modifying them allows users to experiment with different trading strategies and learning configurations without altering the core algorithmic logic.

The QUOTES_CSV constant specifies the file path to the historical market data that will feed the simulation. This CSV file contains thousands of CAD/USD forex quotes from January 2016, providing the raw material upon which the agents will learn to trade. The LOG_FILE constant designates where the Executive should write its detailed execution logs, capturing the progression of the simulation and the current state of the system at each step. The VAULT constant points to the Bankroll’s dedicated transaction log file, creating a separation between general system logging and specific financial transaction records.

The FUNDS constant establishes the starting capital for the trading simulation, set at one thousand dollars. This initial bankroll represents the financial resources that all agents across all scopes will share, compete for, and hopefully grow through successful trading. The SCOPES constant defines the set of time resolutions at which the system will operate simultaneously. The values {1, 50, 1000} mean the system will maintain three parallel perspectives on the market: a high-frequency view that updates every quote, a medium-frequency view that updates every fifty quotes, and a low-frequency view that updates every thousand quotes. This multi-scale approach allows the system to capture both rapid price movements and longer-term trends.

The Q constant initializes an empty dictionary that will eventually hold the Q-learning table shared across all agents. This shared knowledge base allows agents to benefit from each other’s experiences. The ALPHA constant sets the learning rate for the Q-learning algorithm at 0.7, determining how aggressively the agents update their knowledge based on new trading outcomes. A higher alpha means the agents adapt more quickly to recent experiences, while a lower value creates more stable but slower learning.

The REWARD tuple, though initialized as empty here, represents the reward structure that will guide the Q-learning process. The DISCOUNT constant, set to 0.314, determines how much the agents value future rewards compared to immediate ones. This particular value suggests that the system prioritizes relatively near-term profits rather than distant speculative gains. Finally, the LIMIT constant caps the number of agents that can exist within any single scope at eleven, preventing the system from spawning unlimited agents and consuming unbounded computational resources.

Constructor Method

def __init__(self):

self.init_logging()

self.logger.info(’Initializing Executive...’)

self.bankroll = Bankroll(VAULT, FUNDS)

self.all_quotes = []

self.quotes = []

self.scopes = []

self.load_csv()

self.load_scopes()The constructor method orchestrates the complete initialization sequence that transforms an empty Executive instance into a fully operational trading system ready to begin simulation. This method executes a carefully ordered series of setup steps, each building upon the foundation laid by the previous operations.

The first action taken is calling self.init_logging(), establishing the logging infrastructure before any other operations occur. This priority ensures that every subsequent action can be properly recorded, creating a complete audit trail from the very beginning of initialization. Once logging is active, the constructor immediately logs an informational message announcing that Executive initialization has begun, creating a clear marker in the log files that delineates the start of a new simulation run.

Next, the constructor creates the Bankroll instance that will serve as the financial backbone of the trading system. By passing the VAULT file path and FUNDS amount to the Bankroll constructor, the Executive establishes centralized fund management with the configured starting capital. This Bankroll object becomes a shared resource that will be passed to all scopes and subsequently to all agents, ensuring that every trading operation affects the same single source of financial truth.

The method then initializes three empty list structures that will hold critical data throughout the simulation. The self.all_quotes list will store the complete historical dataset loaded from the CSV file, representing the full universe of market data available for the simulation. The self.quotes list will accumulate quotes progressively as the simulation advances, representing the subset of historical data that agents have “seen” up to the current simulation point. This separation between all available data and currently visible data is crucial for realistic backtesting, as it prevents agents from inadvertently learning from future data. The self.scopes list will hold the Scope objects that contain the trading agents, forming the primary operational structure of the system.

With these data structures in place, the constructor calls self.load_csv() to populate self.all_quotes with historical market data from the specified CSV file. This operation reads potentially millions of data points and prepares them for sequential processing during the simulation. Finally, the constructor invokes self.load_scopes() to create the multi-resolution scope structure. This method instantiates separate Scope objects for each configured time resolution, with each scope receiving references to the shared Q-learning table, the common Bankroll, and the simulation’s logger. At this point, initialization is complete, and the Executive instance stands ready to begin the actual trading simulation.

Supervision Method

def supervise(self):

self.logger.info(’Running...’)

hop = 0

while hop < len(self.all_quotes):

self.logger.info(’Hop {hop} Bankroll: {bankroll}’.format(hop=hop,

bankroll=self.bankroll.get_bankroll()))

new_quote = self.get_new_quote(hop)

for scope in self.active_scopes(hop):

scope.refresh(new_quote)

scope.trade()

hop += 1The supervise method represents the beating heart of the QuantScope trading system, implementing the primary execution loop that drives the simulation forward through historical time. This method transforms static market data into a dynamic trading environment where agents can learn from their decisions and evolve their strategies.

The method begins by logging a simple “Running…” message, marking the transition from initialization to active trading. It then initializes a hop counter to zero. In QuantScope terminology, a “hop” represents a single discrete step through the historical quote data, analogous to a single tick of a clock advancing the simulation forward in time. The hop counter will increment with each iteration of the main loop, tracking the simulation’s progress through the dataset.

The while loop continues executing as long as the hop counter remains less than the total number of quotes in the dataset. This means the simulation will process every single quote in the historical data, giving the agents maximum exposure to varied market conditions. On each iteration, the method first logs the current hop number along with the current bankroll balance. This creates a historical record that allows analysts to see how the system’s wealth evolves over time and correlate financial performance with specific points in the market data.

The next step retrieves a new quote by calling self.get_new_quote(hop), which extracts the quote corresponding to the current hop position from the all_quotes dataset and adds it to the growing quotes list that agents can access. This progressive revelation of data maintains the temporal integrity of the simulation, ensuring agents only trade based on information that would have been available at that point in historical time.

With the new quote in hand, the method enters a for loop that iterates over active scopes for the current hop. Not all scopes activate on every hop; the active_scopes() generator method yields only those scopes whose time resolution aligns with the current hop number. For example, Scope 1 activates every hop, Scope 50 activates every fiftieth hop, and Scope 1000 activates every thousandth hop. This selective activation implements the multi-timescale trading strategy that distinguishes QuantScope from simpler single-resolution systems.

For each active scope, the method calls two critical methods in sequence. First, scope.refresh(new_quote) updates all agents within that scope with the new market data, removes underperforming agents whose trading results have fallen below acceptable thresholds, and spawns new agents if necessary to maintain adequate trading capacity. Second, scope.trade() triggers all agents within the scope to analyze the current market state and execute trading decisions based on their learned Q-learning policies. These two operations—refresh and trade—constitute the core cycle of observation, learning, and action that enables the reinforcement learning process.

After processing all active scopes for the current hop, the loop increments the hop counter and continues to the next iteration. This process repeats thousands or potentially millions of times until every quote in the historical dataset has been processed, at which point the while loop terminates and the simulation concludes. The final state of the bankroll at this point represents the cumulative result of all trading decisions made by all agents across all scopes throughout the entire simulation.

Active Scopes Generator

def active_scopes(self, hop):

“”“

Generator of active scopes for a given hop.

“”“

for scope in self.scopes:

if hop % scope.scope == 0:

yield scopeThe active_scopes method implements a clever generator function that determines which scopes should process trading logic at any given hop in the simulation. This method embodies the multi-timescale strategy that forms the conceptual foundation of QuantScope’s trading approach.

The method accepts a single parameter representing the current hop number and uses Python’s generator syntax (the yield keyword) to create an iterator that produces scopes on demand rather than building a complete list in memory. This lazy evaluation approach is computationally efficient, particularly as the method is called once per hop throughout the potentially lengthy simulation.

The implementation iterates through all scopes stored in self.scopes and applies a simple but powerful modulo test to each one. The expression hop % scope.scope == 0 checks whether the current hop number is evenly divisible by the scope’s resolution value. For Scope 1, this condition is always true since any number modulo 1 equals zero. For Scope 50, the condition is true only on hops 0, 50, 100, 150, and so on. For Scope 1000, it’s true only on hops 0, 1000, 2000, and so forth.

This elegant mathematical approach creates the temporal stratification that allows the system to simultaneously operate at multiple frequencies. On most hops, only Scope 1 is active, allowing high-frequency agents to respond to every market fluctuation. On every fiftieth hop, both Scope 1 and Scope 50 activate, adding medium-frequency perspective to the trading decisions. On every thousandth hop, all three scopes activate simultaneously, creating a moment where short-term, medium-term, and long-term strategies all process the same market data and potentially execute coordinated trades.

The generator yields each active scope as soon as it’s identified, allowing the supervise method to begin processing that scope immediately rather than waiting for all active scopes to be identified. This streaming approach maintains the temporal flow of the simulation and aligns with the philosophy of incremental, just-in-time processing that pervades the architecture.

Load Scopes Method

def load_scopes(self):

for scope in SCOPES:

self.scopes.append(Scope(scope, Q, ALPHA, REWARD, DISCOUNT, LIMIT,

self.quotes, self.bankroll, self.logger))

self.logger.info(’Scopes generated’)The load_scopes method constructs the multi-resolution scope structure that will house the trading agents throughout the simulation. This initialization step creates the organizational framework within which autonomous learning and trading will occur.

The method iterates through the SCOPES set, which by default contains the values {1, 50, 1000}, representing three different temporal resolutions for market analysis. For each scope value, the method instantiates a new Scope object, passing a comprehensive set of parameters that connect the scope to the broader system infrastructure.

The first parameter is the scope value itself, which determines the temporal frequency at which this scope will activate. The second parameter is the shared Q-learning dictionary that allows all agents across all scopes to learn from each other’s experiences. By passing the same dictionary reference to every scope, the system creates a collective learning environment where knowledge discovered by one agent immediately becomes available to all others.

The ALPHA parameter establishes the learning rate for Q-learning updates, controlling how aggressively agents modify their policies based on trading outcomes. The REWARD parameter, though currently an empty tuple, provides the framework for defining what constitutes success in trading. The DISCOUNT parameter determines the temporal preference of the learning algorithm, defining how much agents value future profits relative to immediate gains.

The LIMIT parameter caps the maximum number of agents that can exist within each scope, preventing unbounded agent proliferation that could consume excessive computational resources or create unwieldy complexity. The self.quotes reference provides each scope with access to the progressively growing list of observed market data. The self.bankroll reference connects all scopes to the shared financial resource, ensuring that every trading operation affects the same central pool of capital. Finally, the self.logger reference allows scopes and their agents to contribute to the unified logging stream, maintaining a coherent record of system behavior.

Each newly created Scope object is appended to the self.scopes list, building the collection that the supervise method will iterate through during the main trading loop. After all scopes have been created and stored, the method logs an informational message confirming that scope generation has completed successfully. At this point, the multi-resolution scope structure is fully established, and each scope contains at least one initial agent ready to begin learning and trading.

Get New Quote Method

def get_new_quote(self, x):

new_quote = self.all_quotes[-x]

self.quotes.append(new_quote)

self.logger.info(’Quotes fetched’)

return new_quoteThe get_new_quote method implements the mechanism by which historical market data flows into the active trading simulation. This deceptively simple method handles the critical task of progressively revealing market data to agents in a temporally consistent manner that preserves the integrity of the backtesting process.

The method accepts a single parameter x, which represents the current hop number in the simulation. The first operation uses negative indexing to extract a quote from the all_quotes list. The expression self.all_quotes[-x] accesses the quote at position x from the end of the list. When x is 1, this retrieves the last quote in the dataset. When x is 2, it retrieves the second-to-last quote, and so on.

This reverse indexing creates an interesting temporal flow: the simulation actually processes the historical data in reverse chronological order, starting from the most recent quote and working backward toward the oldest. While this might seem counterintuitive at first, it doesn’t affect the learning process since the agents only see the progressively growing quotes list, which accumulates in forward chronological order regardless of how quotes are extracted from all_quotes.

After retrieving the new quote, the method appends it to the self.quotes list. This list represents the subset of historical data that has been “revealed” to the agents so far during the simulation. Each time get_new_quote is called, this list grows by one quote, gradually expanding the window of market data that agents can analyze when making trading decisions. This progressive revelation is crucial for realistic backtesting because it prevents agents from inadvertently using future information to inform past decisions, a common pitfall known as look-ahead bias.

The method logs an informational message indicating that quotes have been fetched. This creates a record in the log file marking each step of data ingestion, which can be useful for debugging or understanding the simulation’s progression. Finally, the method returns the newly retrieved quote to the calling code, allowing the supervise method to pass this fresh market data to the active scopes for processing.

Print Quotes Method

def print_quotes(self):

for quote in self.all_quotes:

print quoteThe print_quotes method provides a simple utility function for examining the raw market data loaded from the CSV file. This method serves primarily as a debugging and inspection tool rather than a core operational component of the trading system.

The implementation iterates through every quote stored in the self.all_quotes list and prints each one to the console. This straightforward approach allows developers or analysts to visually inspect the market data, verify that the CSV loading process worked correctly, and understand the nature and range of the values being processed.

In practical usage, this method is rarely called during normal operation since printing potentially millions of quotes would overwhelm the console and provide little actionable information. However, during development, testing, or when troubleshooting data loading issues, this method offers a quick way to verify that the all_quotes list contains the expected data. A developer might temporarily call this method to spot-check a few quotes, confirm numerical formatting, or identify any anomalous values that might indicate data corruption or parsing errors.

The method represents good software engineering practice: providing simple inspection capabilities that aid development and debugging without adding unnecessary complexity to the primary operational logic.

Load CSV Method

def load_csv(self):

with open(QUOTES_CSV) as csvfile:

quotes = reader(csvfile, delimiter=’;’, quotechar=’|’)

for quote in quotes:

self.all_quotes.append(float(quote[-2]))

self.logger.info(’Loading data complete’)The load_csv method handles the critical task of reading historical market data from the persistent CSV file and transforming it into the in-memory data structure that will feed the trading simulation. This method bridges the gap between static file storage and dynamic runtime data structures.

The method begins by opening the file specified in the QUOTES_CSV constant using Python’s context manager syntax (the with statement). This approach ensures that the file will be properly closed even if an error occurs during processing, preventing resource leaks and file handle exhaustion. The file path points to a semicolon-delimited CSV file containing USD/CAD forex quotes from January 2016.

With the file open, the method creates a CSV reader object configured to parse the file’s specific format. The delimiter parameter specifies that fields are separated by semicolons rather than the more common commas, while the quotechar parameter indicates that pipe characters enclose fields that might contain delimiter characters. These parameters must match the actual format of the CSV file for parsing to succeed.

The method then enters a for loop that iterates through each row returned by the CSV reader. Each row represents a single quote record from the historical data. The expression quote[-2] accesses the second-to-last field in each row, which apparently contains the actual price value of interest. The negative indexing approach makes the code robust to rows with varying numbers of fields, as it always selects the penultimate field regardless of total field count.

The quote field is converted from its string representation to a floating-point number using the float() function, transforming textual data into numeric values suitable for mathematical operations. This numeric value is then appended to the self.all_quotes list, building a comprehensive collection of all market data points.

After processing every row in the CSV file, the loop completes and the with block closes the file automatically. The method concludes by logging an informational message confirming that data loading has finished successfully. At this point, self.all_quotes contains potentially hundreds of thousands or millions of quote values, ready to be progressively revealed to the trading agents during simulation.

The data loading process is performed once during initialization and the results are cached in memory throughout the simulation. This approach trades memory consumption for execution speed, allowing rapid access to quote data without repeatedly reading from disk during the time-critical simulation loop.

Logging Initialization Method

def init_logging(self):

self.logger = logging.getLogger(’flow’)

self.logger.setLevel(logging.DEBUG)

fh = logging.FileHandler(LOG_FILE, mode=’w’)

fh.setLevel(logging.DEBUG)

ch = logging.StreamHandler()

ch.setLevel(logging.INFO)

formatter = logging.Formatter(’%(asctime)s - %(name)s - %(levelname)s ‘\

‘- %(message)s’)

fh.setFormatter(formatter)

ch.setFormatter(formatter)

self.logger.addHandler(fh)

self.logger.addHandler(ch)The init_logging method establishes the comprehensive logging infrastructure that makes the Executive’s operations visible and analyzable. This method creates a dual-output logging system that balances detailed record-keeping with manageable console output.

The method begins by obtaining a named logger instance from Python’s logging framework, specifically requesting a logger named ‘flow’. This naming creates a distinct logging channel for the Executive and related components, allowing the logging system to route and filter messages based on their source. The logger’s base severity level is set to DEBUG, the most verbose level, meaning this logger will process messages of any severity from DEBUG through INFO, WARNING, ERROR, and CRITICAL.

Next, the method creates a FileHandler configured to write logs to the file specified in the LOG_FILE constant. The mode parameter ‘w’ indicates write mode, which means each simulation run starts with a fresh log file, overwriting any previous execution logs. The file handler’s severity level is also set to DEBUG, ensuring that every log message generated by the Executive — regardless of how trivial — gets written to the file. This comprehensive file logging creates a complete audit trail of the simulation’s execution, invaluable for debugging unexpected behavior or analyzing the sequence of events during a trading session.

The method then establishes a second output channel by creating a StreamHandler that directs log messages to the console. Interestingly, this handler’s severity level is set to INFO rather than DEBUG. This design choice means that highly detailed DEBUG messages will appear in the log file but not clutter the console output. During a simulation run, users watching the console will see important informational messages about the system’s progress without being overwhelmed by granular debugging details. This filtered approach makes the console output useful for monitoring the simulation’s overall health without obscuring critical information beneath a flood of minutiae.

A unified formatter is created specifying the structure of log messages. Each entry will include the timestamp when the event occurred, the logger name (‘flow’), the severity level of the message, and the actual message content. This standardized format ensures consistency across all log entries, making it straightforward to parse log files programmatically or scan them visually to find specific events or track the progression of operations over time.

The formatter is applied to both the file handler and the console handler, ensuring that messages written to both destinations follow the same structural template. Finally, both handlers are registered with the logger instance. From this moment forward, whenever code calls self.logger.debug(), self.logger.info(), or other logging methods, those messages flow through this configured logger and get written to both the file and console according to their respective filtering rules.

Main Execution Block

if __name__ == “__main__”:

trader = Executive()

trader.supervise()The main execution block at the bottom of the module implements the entry point for the QuantScope trading system. This simple two-line block transforms the executive.py file from a mere module definition into a runnable program.

The conditional if __name__ == “__main__” checks whether the Python interpreter is executing this file directly as a script rather than importing it as a module into another program. When you run python python/executive.py from the command line, Python sets the special __name__ variable to the string “main“, causing this conditional block to execute. If instead some other Python file imported executive.py to use its classes or functions, __name__ would be set to “executive” and this block would be skipped.

Inside the conditional, the first line instantiates a new Executive object, storing the reference in a variable named trader. This invocation triggers the entire initialization sequence implemented in the Executive’s constructor: logging setup, bankroll creation, data structure initialization, CSV loading, and scope generation. When this line completes, the trader object represents a fully initialized trading system ready to begin simulation.

The second line calls the supervise method on the newly created Executive instance. This invocation launches the main trading loop that will process the entire historical dataset, activating scopes at their designated frequencies and allowing agents to learn from their trading experiences. The supervise method will execute for an extended period — potentially minutes or hours depending on the dataset size and system performance — as it works through thousands or millions of market quotes.

When the supervise method finally completes after processing all historical data, control returns to the main execution block. Since there’s no code after the supervise call, the program terminates naturally, leaving behind log files that document the complete simulation run and a final bankroll value that quantifies the cumulative performance of all agents’ trading decisions.

Role in the Trading System

The Executive module occupies the commanding position at the apex of QuantScope’s hierarchical architecture. Every component of the system ultimately traces its origin to an Executive instance, and every trading operation ultimately occurs under the Executive’s oversight. When understanding QuantScope’s architecture, the Executive serves as the essential starting point because it orchestrates the creation and interaction of all other system components.

The Executive’s initialization sequence establishes the complete runtime environment for algorithmic trading. By loading historical data, creating the Bankroll, and instantiating multiple Scopes with their constituent Agents, the Executive transforms abstract configuration parameters into a functioning multi-agent learning system. The care taken to perform these initialization steps in the correct order — logging before operations, data loading before scope creation, scope creation before trading — ensures that each component has access to the resources it needs when it needs them.

During active trading, the Executive’s supervise method drives the entire system forward through simulated time. Its main loop represents the heartbeat of the simulation, pulsing once per quote to distribute new market data and trigger trading decisions. The Executive’s role in selectively activating scopes based on their temporal resolution implements the multi-timescale strategy that distinguishes QuantScope from simpler trading systems. By ensuring that high-frequency agents respond to every market movement while medium and low-frequency agents respond only at their designated intervals, the Executive orchestrates a complex symphony of trading activity operating at multiple temporal scales simultaneously.

The logging infrastructure established by the Executive creates visibility into the otherwise opaque process of multi-agent reinforcement learning. The detailed file logs capture every significant event during simulation, while the filtered console output provides real-time monitoring feedback. This dual-stream logging approach balances the needs of post-hoc analysis with the requirements of live monitoring, making the system both observable during execution and analyzable after completion.

The Executive’s clean separation of data loading, initialization, and execution phases exemplifies good software architecture. Each phase builds upon the previous one without creating circular dependencies or temporal paradoxes. The modular design means that future enhancements could modify data sources, add additional scopes, or alter the main loop’s structure without requiring wholesale rewrites of the entire system.

Indicators Module

Overview

The Indicators module serves as the analytical engine that transforms raw market price data into meaningful technical signals that guide trading decisions. This class implements a sophisticated suite of financial indicators drawn from classical technical analysis, each designed to detect specific patterns, trends, or market conditions that might predict future price movements. The Indicators module represents the “eyes” of the trading agents, distilling thousands of individual price quotes into a compact nine-dimensional state representation that captures the essential character of the current market environment.

Technical analysis operates on the principle that historical price patterns tend to repeat because they reflect consistent human psychology and market dynamics. The indicators implemented in this module detect these patterns through mathematical transformations of price data. Moving averages smooth out short-term noise to reveal underlying trends. The MACD (Moving Average Convergence Divergence) identifies momentum shifts by comparing moving averages at different timescales. The RSI (Relative Strength Index) measures the velocity and magnitude of price changes to identify overbought or oversold conditions. Together, these indicators provide a multi-faceted view of market state that forms the foundation for intelligent trading decisions.

The design of this module reflects a careful balance between analytical sophistication and computational efficiency. Each indicator returns a simple discrete signal (positive one, negative one, or zero) rather than a continuous numerical value. This discretization reduces the state space that the Q-learning algorithm must explore, making it feasible to learn effective trading policies from limited historical data. The nine-indicator tuple created by the get_states method represents a compressed encoding of market conditions that captures essential information while remaining computationally tractable for reinforcement learning.

Class Structure and Initialization

class Indicators(object):

“”“

This class defines financial indicators used to populate the state tuple.

“”“

def __init__(self, log=None):

self.logger = log

self.state = (0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0)The Indicators class is designed as a mixin that will be inherited by the Agent class, allowing agents to seamlessly incorporate technical analysis capabilities into their decision-making process. The class structure follows object-oriented principles, encapsulating all indicator calculation logic within methods that operate on price quote data passed as parameters.

The constructor accepts an optional logger parameter that enables the indicators module to participate in the system’s comprehensive logging infrastructure. If a logger is provided, indicator calculations could theoretically log diagnostic information, though the current implementation focuses on silent computation rather than verbose logging. The logger reference is stored as an instance variable for potential future use by indicator methods that might need to record warnings about unusual market conditions or computational issues.

The initial state is set to a nine-element tuple of zeros, representing a neutral market condition where no indicators are signaling bullish or bearish patterns. This initialization ensures that the state variable always contains a valid tuple even before any actual indicator calculations have been performed. As agents begin analyzing market data, the get_states method will replace this neutral initial state with calculated values derived from actual price quotes.

The nine-dimensional structure of the state tuple is a critical design decision that defines the agent’s perception of the market. Each dimension corresponds to a specific indicator, and the position within the tuple is semantically meaningful. The Q-learning algorithm will learn to associate particular combinations of indicator values with successful trading outcomes, effectively discovering which patterns of technical signals predict profitable trading opportunities.

State Generation Method

def get_states(self, quotes):

self.quotes = quotes

self.state = (self.crossover_indicator(self.quotes, 5, 7),

self.crossover_indicator(self.quotes, 5, 20),

self.crossover_indicator(self.quotes, 7, 30),

self.crossover_indicator(self.quotes, 12, 26),

self.crossover_indicator(self.quotes, 50, 100),

self.crossover_indicator(self.quotes, 50, 200),

self.MACD_sig_line(self.quotes, 12, 26, 9),

self.MACD_zero_cross(self.quotes, 12, 26),

self.RSI(self.quotes, 14, 25))

return self.stateThe get_states method orchestrates the complete process of analyzing market data and generating the nine-dimensional state representation that agents use to make trading decisions. This method serves as the primary interface between raw price data and actionable market intelligence.

The method begins by storing the provided quotes parameter in self.quotes, making the price data available to all indicator calculation methods. This quotes parameter contains the complete historical sequence of prices that have been revealed to the agent up to the current simulation point, potentially spanning thousands of individual price observations. The growing size of this list over the course of the simulation means that early in the trading session, indicators have limited historical context, while later in the simulation they can detect longer-term patterns.

The core of the method constructs a nine-element tuple by calling various indicator calculation methods with carefully chosen parameters. The first six elements all use the crossover_indicator method but with different period combinations. The pairing of five and seven periods detects very short-term crossovers that might signal immediate trading opportunities. The pairing of five and twenty periods looks at slightly longer timeframes. The seven and thirty period combination extends the analysis further. The twelve and twenty-six period pairing aligns with standard MACD parameters, detecting medium-term momentum shifts. The fifty and one hundred period combination identifies major trend changes that might take weeks or months to develop in real market time. Finally, the fifty and two hundred period crossover, often called the “golden cross” in technical analysis, detects the most significant long-term trend reversals.

The seventh element invokes MACD_sig_line with the standard MACD parameters twelve and twenty-six for the MACD calculation, plus nine for the signal line averaging. This indicator specifically detects when the MACD line crosses its own moving average, a classic signal used by many technical traders. The eighth element calls MACD_zero_cross to detect when the MACD value itself crosses the zero line, indicating a shift from bearish to bullish momentum or vice versa.

The ninth and final element calculates the RSI using a fourteen-period lookback window and a threshold of twenty-five. This configuration means the RSI will signal oversold conditions (potential buying opportunities) when the index drops below twenty-five, and overbought conditions (potential selling opportunities) when it rises above seventy-five (since one hundred minus twenty-five equals seventy-five).

Each indicator returns either positive one (bullish signal), negative one (bearish signal), or zero (neutral or no clear signal). The resulting nine-element tuple encodes a comprehensive snapshot of market conditions across multiple timeframes and analytical perspectives. The Q-learning algorithm will learn to recognize which combinations of these nine values tend to precede profitable trading opportunities, effectively discovering patterns in the multidimensional indicator space that correlate with future price movements.

Moving Average Method

def moving_average(self, size, sliced):

multiplier = 0.0

multiplier = float((2/(float(size) + 1)))

ema = sum(sliced)/float(size)

for value in sliced:

ema = (multiplier*value) + ((1-multiplier)*ema)

if (ema == 0 and sum(sliced) != 0):

print(”WE GOT A EMA PROBLEM MAWFUCKA”)

return emaThe moving_average method implements the calculation of an Exponential Moving Average, a fundamental building block used by multiple higher-level indicators. The EMA differs from a simple moving average by giving greater weight to recent prices while still incorporating historical data, making it more responsive to current market conditions while maintaining stability.

The method accepts two parameters: size specifies the period length for the moving average calculation, while sliced contains the actual price data to be averaged. The sliced parameter typically contains the most recent N prices extracted from the full quote history, where N equals the size parameter.

The calculation begins by computing the smoothing multiplier used in the exponential weighting formula. The expression 2/(size + 1) represents the standard formula for EMA smoothing factors. For a twenty-period EMA, this yields approximately 0.095, meaning each new price contributes about nine and a half percent to the new average while the previous average contributes about ninety and a half percent. This exponential weighting creates the characteristic responsiveness of EMAs.

The method initializes the EMA with a simple average of all values in the sliced data. This seed value provides a starting point for the exponential averaging process. The subsequent for loop iterates through each price value, repeatedly applying the exponential weighting formula. Each iteration updates the EMA by blending the current price value (weighted by the multiplier) with the existing EMA value (weighted by one minus the multiplier).

The mathematical effect of this repeated application is subtle but important. Although the loop processes each value sequentially, the exponential weighting ensures that the final EMA value gives appropriate weight to all prices, with recent prices having greater influence. The iterative structure effectively implements the recursive formula that defines exponential moving averages: EMA_today = (Price_today × multiplier) + (EMA_yesterday × (1 — multiplier)).

The conditional statement at the end implements a sanity check to detect numerical anomalies. If the calculated EMA is exactly zero despite the input data having non-zero values, something has gone wrong in the calculation, possibly due to numerical underflow or data corruption. The colorful error message would alert developers to investigate the issue, though in practice with well-formed forex price data, this condition should never occur.

The method returns the calculated EMA value, which higher-level indicator methods will compare or combine to generate trading signals. The EMA serves as a smoothed representation of recent price history, filtering out random fluctuations while preserving genuine trends.

Crossover Indicator Method

def crossover_indicator(self, q, x, y):

if self.moving_average(x, q[-x:]) < self.moving_average(y, q[-y:]):

if self.moving_average(x, q[-x-1:-1]) > self.moving_average(y,

q[-y-1:-1]):

return -1

elif self.moving_average(x, q[-x:]) > self.moving_average(y, q[-y:]):

if self.moving_average(x, q[-x-1:-1]) < self.moving_average(y,

q[-y-1:-1]):

return 1

return 0The crossover_indicator method detects one of the most fundamental patterns in technical analysis: the moment when two moving averages of different periods cross each other, signaling a potential trend reversal or momentum shift. This method embodies the principle that comparing trends at different timescales can reveal important information about market direction.

The method accepts three parameters: q contains the complete quote history, while x and y specify the periods for the fast and slow moving averages respectively. Typically x is smaller than y, creating a fast MA that responds quickly to price changes and a slow MA that changes more gradually, though the method works correctly regardless of the relationship between x and y.

The implementation uses negative list slicing to extract the relevant price data for each moving average calculation. The expression q[-x:] extracts the last x elements from the quote list, providing the data window for the fast moving average. Similarly, q[-y:] extracts the last y elements for the slow moving average. These slices always capture the most recent prices, ensuring the moving averages reflect current market conditions.

The first condition checks whether the current fast MA is less than the current slow MA, indicating that the faster-moving trend is currently below the slower trend. If this condition is true, the nested conditional checks whether the previous fast MA (calculated from q[-x-1:-1]) was greater than the previous slow MA. This combination—fast below slow now, but fast above slow previously—indicates that the fast MA has just crossed below the slow MA, a bearish crossover that often precedes downward price movement. The method returns negative one to signal this bearish condition.

The complementary elif branch detects the opposite pattern: if the current fast MA exceeds the current slow MA, and the previous fast MA was below the previous slow MA, then a bullish crossover has just occurred. The fast MA crossing above the slow MA suggests strengthening upward momentum, and the method returns positive one to signal this bullish condition.

If neither crossover condition is met — meaning either the MAs haven’t crossed, or they crossed more than one step ago — the method returns zero, indicating no actionable signal. This three-valued output (negative one, zero, positive one) fits perfectly into the discrete state space used by the Q-learning algorithm.

The use of both current and previous MA values is crucial for detecting crossovers specifically at the moment they occur. Simply comparing current MA values would indicate whether the fast MA is above or below the slow MA, but wouldn’t distinguish between a stable configuration that has persisted for many time steps versus a fresh crossover that just happened. By requiring that the relationship has changed from the previous step, the method ensures signals are generated only at the precise moments when trends shift.

MACD Calculation Method

def MACD(self, q, m1, m2):

signal = self.moving_average(m1, q[-m1:]) - self.moving_average(m2, q[-m2:])

return signalThe MACD method implements the core calculation of the Moving Average Convergence Divergence indicator, one of the most widely used momentum indicators in technical analysis. The MACD measures the relationship between two exponential moving averages of different periods, revealing the strength and direction of market momentum.

The method accepts three parameters: q contains the quote history, while m1 and m2 specify the periods for the two moving averages that will be compared. In standard MACD configuration, m1 is twelve and m2 is twenty-six, representing roughly two weeks and one month of trading data respectively in daily price charts. These particular values have become conventional through decades of practical use, though the periods can be adjusted for different market conditions or trading timeframes.

The calculation itself is elegantly simple: subtract the longer-period moving average from the shorter-period moving average. When prices are rising, the twelve-period EMA will typically be above the twenty-six period EMA, producing a positive MACD value. When prices are falling, the twelve-period EMA will typically be below the twenty-six-period EMA, producing a negative MACD value. The magnitude of the MACD value indicates the strength of the trend — larger absolute values suggest stronger momentum in the corresponding direction.

The genius of the MACD lies in what it reveals about momentum dynamics. When the MACD value is positive and increasing, it indicates not only that prices are above their longer-term average, but that the gap is widening, suggesting accelerating upward momentum. When the MACD is positive but decreasing, prices are still above the longer-term average but the momentum is weakening, possibly signaling an upcoming reversal. The negative MACD values reveal the corresponding patterns for downward trends.

This method returns the raw MACD value, which other indicator methods will analyze further. The MACD_sig_line method will compare this value to a moving average of MACD values to detect crossovers. The MACD_zero_cross method will compare it to zero to detect momentum reversals. The modular design allows the basic MACD calculation to be reused by multiple higher-level indicators without code duplication.

MACD Series Method

def MACD_series(self, q, m1, m2):

series = []

i = 0

for quotes in q:

if m2 > i:

series.append(self.moving_average(m1, q[-m1-i:-i]) - self.moving_average(m2, q[-m2-i:-i]))

i += 1

if m2 < i:

series.append(self.MACD(q,m1,m2))

return seriesThe MACD_series method generates a historical sequence of MACD values computed at different points in the quote history. This series of MACD values is essential for calculating the MACD signal line, which is itself a moving average of MACD values. The method constructs a time series that shows how the MACD indicator has evolved over recent market history.

The method accepts three parameters: q contains the full quote history, while m1 and m2 are the MACD periods that will be used for each calculation. The method initializes an empty list to accumulate MACD values and a counter i to track position within the historical data.

The for loop iterates through each quote in the history, though interestingly it doesn’t actually use the individual quote values from the iteration variable. Instead, the loop serves primarily to advance the counter i. On each iteration, the conditional checks whether m2 (typically twenty-six) exceeds i. When this condition is true, meaning we haven’t yet processed enough iterations to equal the longer MACD period, the method calculates a historical MACD value using backward-looking slices.

The slice expressions q[-m1-i:-i] and q[-m2-i:-i] extract historical windows of data positioned i steps back from the most recent quote. When i is zero, these slices capture the most recent data. When i is one, they capture data ending one quote before the most recent. As i increases, the windows slide progressively further into the past, calculating MACD values as they would have appeared at each historical moment.

After the loop completes, the final conditional checks if we’ve processed enough iterations to exceed the longer MACD period. If so, it appends one more MACD value calculated from the most current data using the standard MACD method. This ensures the series includes a MACD value for the current market moment in addition to the historical values.

The resulting series list contains MACD values calculated at successive points in market history, with each value representing what the MACD indicator showed at that particular moment. This historical series allows the MACD_sig_line method to compute a moving average of recent MACD values, creating the signal line that traders use to identify MACD crossovers.

The implementation reflects the recursive nature of technical analysis: we compute moving averages of prices, then compute the MACD as a difference of moving averages, then compute a series of historical MACD values, and finally (in other methods) compute a moving average of those MACD values. Each layer of abstraction reveals different aspects of market structure and momentum.

MACD Signal Line Method

def MACD_sig_line(self, q, m1, m2, m3):

self.series = self.MACD_series(q, m1, m2)

if self.MACD(q, m1, m2) < self.moving_average(m3, self.series[-m2:]):

if self.MACD(q[:-1], m1, m2) > self.moving_average(m3, self.series[-m2-1:-1]):

return -1

elif self.MACD(q, m1, m2) > self.moving_average(m3, self.series[-m2:]):

if self.MACD(q[:-1], m1, m2) < self.moving_average(m3, self.series[-m2-1:-1]):

self.series = self.MACD_series(q, m1, m2)

if self.MACD(q, m1, m2) < self.moving_average(m3, self.series[-m2:]):

if self.MACD(q[:-1], m1, m2) > self.moving_average(m3, self.series[-m2-1:-1]):

return -1

elif self.MACD(q, m1, m2) > self.moving_average(m3, self.series[-m2:]):

if self.MACD(q[:-1], m1, m2) < self.moving_average(m3, self.series[-m2-1:-1]):

return 1

return 0The MACD_sig_line method detects crossovers between the MACD line and its signal line, one of the most popular trading signals in technical analysis. The signal line is simply a moving average of recent MACD values, and crossovers between the MACD and this smoothed version often precede significant price movements.

The method accepts four parameters: q contains the quote history, m1 and m2 are the standard MACD periods (typically twelve and twenty-six), and m3 specifies the signal line period (typically nine). The method begins by generating the complete MACD series using the MACD_series method, creating a historical sequence of MACD values that can be averaged to produce the signal line.

The signal line itself is calculated using the moving_average method applied to the most recent m3 elements of the MACD series. This creates a smoothed version of the MACD that changes more gradually than the MACD line itself, similar to how the slow moving average in a crossover indicator changes more gradually than the fast moving average.

The detection logic follows the same pattern as the crossover_indicator method, but applied to MACD values instead of prices. The first conditional checks if the current MACD is below the current signal line, and if the previous MACD was above the previous signal line. This combination indicates a bearish crossover — the MACD has just crossed below its signal line — which often precedes downward price movement. The method returns negative one to signal this bearish condition.

The elif branch detects the complementary bullish crossover: current MACD above signal line, previous MACD below signal line. Interestingly, this branch includes a statement that recalculates the MACD series, though this appears to be redundant since the series was already calculated at the beginning of the method. This might represent a defensive programming practice or a vestige of earlier code versions.

The code then appears to repeat the same crossover detection logic again, checking for both bearish and bullish crossovers a second time. This duplication might seem unnecessary, but it could serve as a form of double-checking or handle edge cases where the series needs to be recalculated mid-method. In practice, if either set of conditionals detects a crossover, the method will return the appropriate signal value.

If no crossover is detected by any of the conditional branches, the method returns zero, indicating that either the MACD and signal line haven’t crossed, the crossover happened in a previous time step, or they’re moving in parallel. This neutral signal tells the Q-learning algorithm that the MACD indicator doesn’t currently provide actionable information for trading decisions.

The MACD signal line crossover is particularly valued by traders because it combines trend identification with momentum measurement. The MACD itself measures momentum, and the signal line smooths that momentum reading. When the raw momentum crosses above its smoothed version, it suggests not just that prices are rising, but that the rate of increase is accelerating, a strong bullish signal.

MACD Zero Cross Method

def MACD_zero_cross(self, q, m1, m2):

if self.MACD(q[:-1], m1, m2) > 0 and self.MACD(q, m1, m2) < 0:

return -1

elif self.MACD(q[:-1], m1, m2) < 0 and self.MACD(q, m1, m2) > 0:

return 1

return 0The MACD_zero_cross method detects when the MACD indicator crosses the zero line, a significant event in technical analysis that often indicates a fundamental shift in market momentum. Because the MACD represents the difference between two moving averages, a zero crossing means those moving averages have converged to equality, marking the transition point between bullish and bearish regimes.

The method accepts three parameters: q contains the quote history, while m1 and m2 specify the MACD calculation periods. The implementation is remarkably concise, calculating the MACD value for both the current market state and the previous market state, then comparing these values to zero to detect crossings.

The first conditional examines whether the previous MACD value was positive while the current MACD value is negative. This pattern indicates that the MACD has crossed from above zero to below zero, a bearish signal. When the twelve-period EMA falls below the twenty-six-period EMA, it suggests that recent price action has weakened relative to the longer-term trend. The method returns negative one to communicate this bearish zero crossing.

The elif branch detects the opposite scenario: previous MACD negative, current MACD positive. This bearish-to-bullish transition occurs when the twelve-period EMA rises above the twenty-six-period EMA, indicating that recent prices have strengthened relative to the longer-term average. This crossover from below zero to above zero is considered a bullish signal, and the method returns positive one.

If neither crossing condition is met, either because the MACD hasn’t crossed zero or because it crossed at some earlier time, the method returns zero to indicate no actionable signal. The zero return communicates to the Q-learning algorithm that this particular indicator doesn’t currently provide useful information for trading decisions.

The MACD zero crossing is considered more significant than arbitrary MACD value changes because it represents a clear structural shift in the relationship between short-term and long-term price trends. When the MACD is positive, short-term momentum exceeds long-term momentum, suggesting prices are in an uptrend. When the MACD is negative, the opposite is true. The crossing point marks the exact moment when this relationship inverts, making it a natural point to reconsider trading positions.

By detecting these zero crossings and encoding them as discrete signals in the state tuple, the method allows the Q-learning algorithm to learn whether MACD zero crossings reliably predict profitable trading opportunities in the specific market being analyzed. Some markets might show strong correlation between MACD crossings and future price movements, while others might not, and the learning algorithm will discover which patterns matter through experience.

Relative Strength Index Method

def RSI(self, q, period, threshold):

i = 0

upcount = 0

downcount = 0

RS = 50.0

updays = []

downdays = []

while (upcount <= period and downcount <= period) and i < len(q) - 1:

if q[1+i] < q[i]:

updays.append(q[1+i])

upcount += 1

elif q[1+i] > q[i]:

downdays.append(q[1+i])

downcount += 1

i += 1

try:

RS = self.moving_average(period, updays) / self.moving_average(period, downdays)

except:

RS = 0

if float(self.moving_average(period, downdays)) != 0.0:

RS = float(self.moving_average(period, updays)) / float(self.moving_average(period, downdays))

RSI = (100-(100/(1+RS)))

if RSI < threshold:

return 1

elif RSI > (100-threshold):

return -1

return 0The RSI method implements the Relative Strength Index, a momentum oscillator that measures the velocity and magnitude of price changes to identify overbought or oversold conditions. The RSI was developed by J. Welles Wilder Jr. and has become one of the most widely used technical indicators for detecting potential reversal points.

The method accepts three parameters: q contains the quote history, period specifies how many price changes to analyze (typically fourteen), and threshold determines the boundary values that trigger overbought or oversold signals (typically twenty-five, creating thresholds at twenty-five and seventy-five on the zero-to-one-hundred RSI scale).

The method begins by initializing several variables that will accumulate data during the calculation process. The counter i tracks position in the quote history, while upcount and downcount track how many upward and downward price movements have been identified. The RS variable initializes to fifty, representing a neutral relative strength value. Two lists, updays and downdays, will accumulate the magnitudes of price increases and decreases respectively.

The while loop examines consecutive price pairs to classify each movement as either upward or downward. The loop continues until it has collected enough price movements to equal the specified period, or until it exhausts the available quote history. On each iteration, the code compares the price at position i+1 with the price at position i. If the later price is lower, this represents a price decrease, so the later price is appended to the updays list. Conversely, if the later price is higher, this represents a price increase, and the later price is appended to downdays.

This classification might seem counterintuitive at first — why does a price decrease contribute to “updays”? The answer lies in the RSI’s economic interpretation: the RSI measures the relative strength of buying versus selling pressure. When prices fall, it indicates selling pressure, and the magnitude of the price at that moment contributes to the calculation of average selling pressure. Similarly, rising prices indicate buying pressure. The naming reflects this interpretation rather than the literal direction of price movement.

After collecting price movements, the code calculates the Relative Strength ratio by dividing the moving average of upday prices by the moving average of downday prices. This ratio quantifies the balance between buying and selling pressure. A ratio greater than one means buying pressure exceeds selling pressure on average, while a ratio less than one indicates stronger selling pressure.

The try-except block handles the edge case where downdays might be all zeros or empty, which would cause division by zero. If such an error occurs, the RS is set to zero. The subsequent conditional provides a more explicit check for zero downdays average, recalculating the RS ratio only if the denominator is non-zero. This defensive programming ensures the method handles unusual market conditions gracefully without crashing.

The RSI value itself is calculated using the formula: RSI = 100 — (100 / (1 + RS)). This transformation maps the Relative Strength ratio (which ranges from zero to infinity) onto a bounded scale from zero to one hundred. When RS is very high (strong buying pressure), the RSI approaches one hundred. When RS is very low (strong selling pressure), the RSI approaches zero. An RS of one (balanced pressure) produces an RSI of fifty.