Understanding How Large Language Models Store Facts

Large language models (LLMs) like GPT-3 have demonstrated an impressive ability to recall and generate factual information.

For instance, when prompted with the phrase “Michael Jordan plays the sport of ___,” an LLM accurately predicts “basketball.” This capability suggests that within the model’s hundreds of billions of parameters lies embedded knowledge about specific individuals and their associated domains. But how exactly do these models store and retrieve such facts? To unravel this mystery, we delve into the intricate mechanisms that underpin LLMs, exploring their architecture, the flow of information, and the sophisticated ways they manage to encode vast amounts of knowledge.

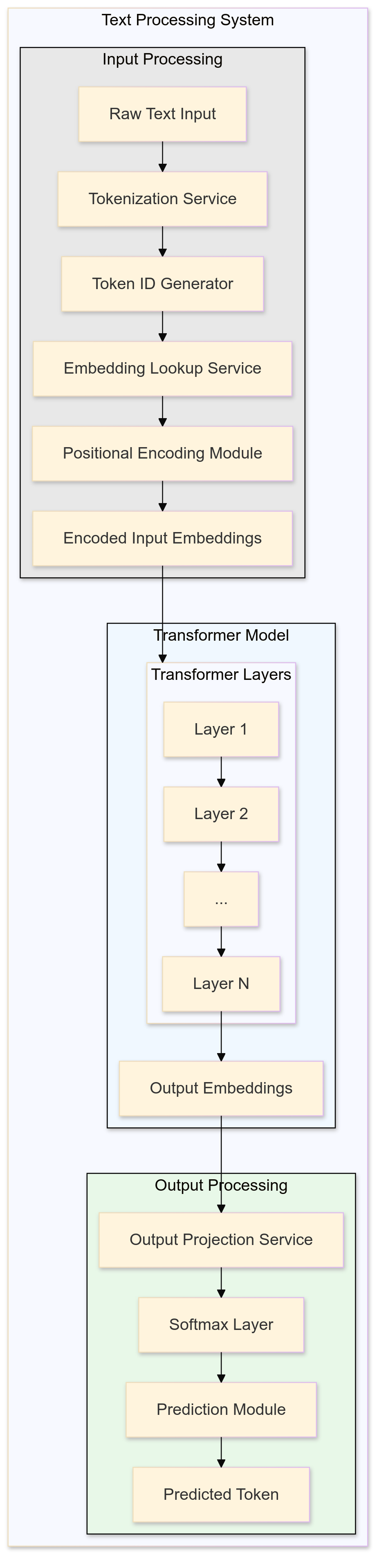

At the heart of modern natural language processing (NLP) lies the Transformer architecture, a groundbreaking innovation that has revolutionized the field. Transformers enable models to handle sequential data more effectively than their predecessors, such as recurrent neural networks (RNNs). A key feature of Transformers is the Attention mechanism, which allows models to dynamically focus on different parts of the input data. This ability to weigh the importance of various tokens in a sequence enables Transformers to capture long-range dependencies and complex relationships within the data.

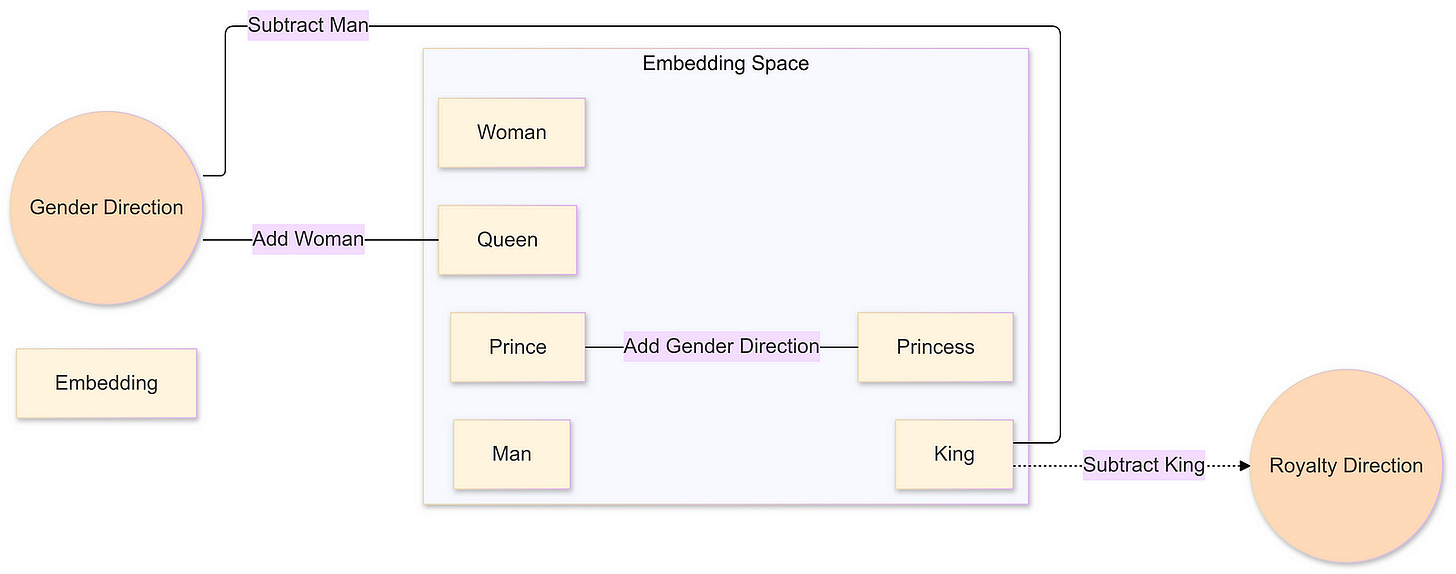

The process begins with input text being tokenized into smaller units called tokens, which can be entire words or subwords. Each token is then associated with a high-dimensional vector known as an embedding. These embeddings reside in a continuous vector space where semantic relationships between words can be captured through geometric operations. For example, the famous vector arithmetic operation “king” — “man” + “woman” ≈ “queen” illustrates how embeddings can encode intricate linguistic patterns and relationships.

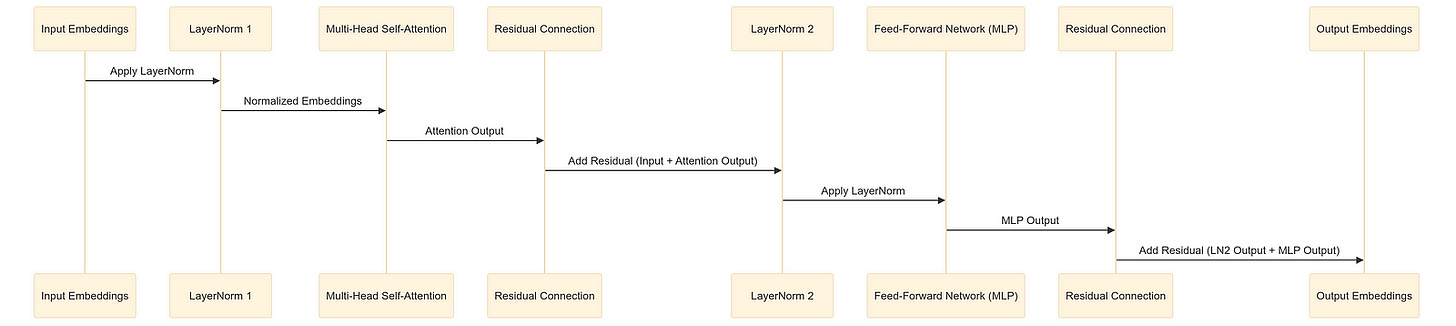

Detailed Transformer Architecture Diagram:

As these embeddings flow through the Transformer, they pass through multiple layers of Attention mechanisms and Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs), interspersed with Layer Normalization steps. The Attention mechanism allows the model to weigh the significance of different tokens relative to each other, effectively capturing dependencies regardless of their position in the sequence. Meanwhile, the MLPs play a crucial role in processing information that the attention mechanisms alone cannot capture.

Detailed Flow of Embeddings Through Transformer Layers:

A fundamental aspect of understanding how LLMs store facts lies in comprehending the high-dimensional vector spaces in which these embeddings reside. In these spaces, different directions can encode various kinds of meanings. For example, one direction might represent gender information, as illustrated by the relationship between the embeddings of “woman” and “man.” Vectors flowing through the network imbibe richer meanings based on the surrounding context and the model’s internal knowledge, enabling each embedding to encapsulate far more than the meaning of a single word. This rich encoding is essential for the model’s ability to predict subsequent tokens accurately.

Visualization of Embedding Space Directions:

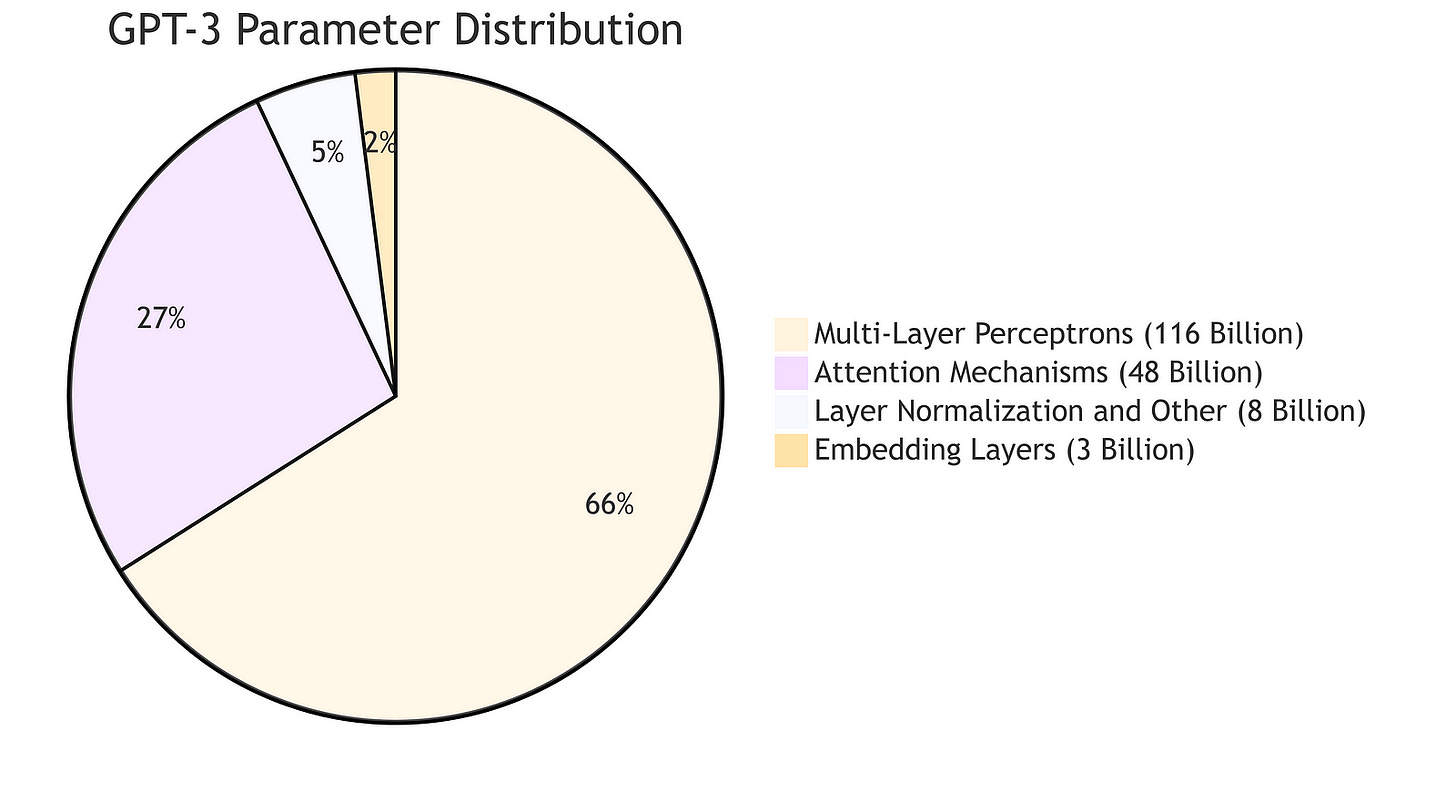

Focusing on the role of Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs) within Transformers reveals that MLPs constitute a significant portion of the model’s parameters. These MLPs are responsible for processing and transforming the embeddings in ways that allow the model to store and retrieve factual information. The computational steps within an MLP are relatively straightforward, involving two matrix multiplications with a non-linear activation function sandwiched in between. Despite their simplicity, these operations are performed at a massive scale, enabling the model to handle complex data transformations.

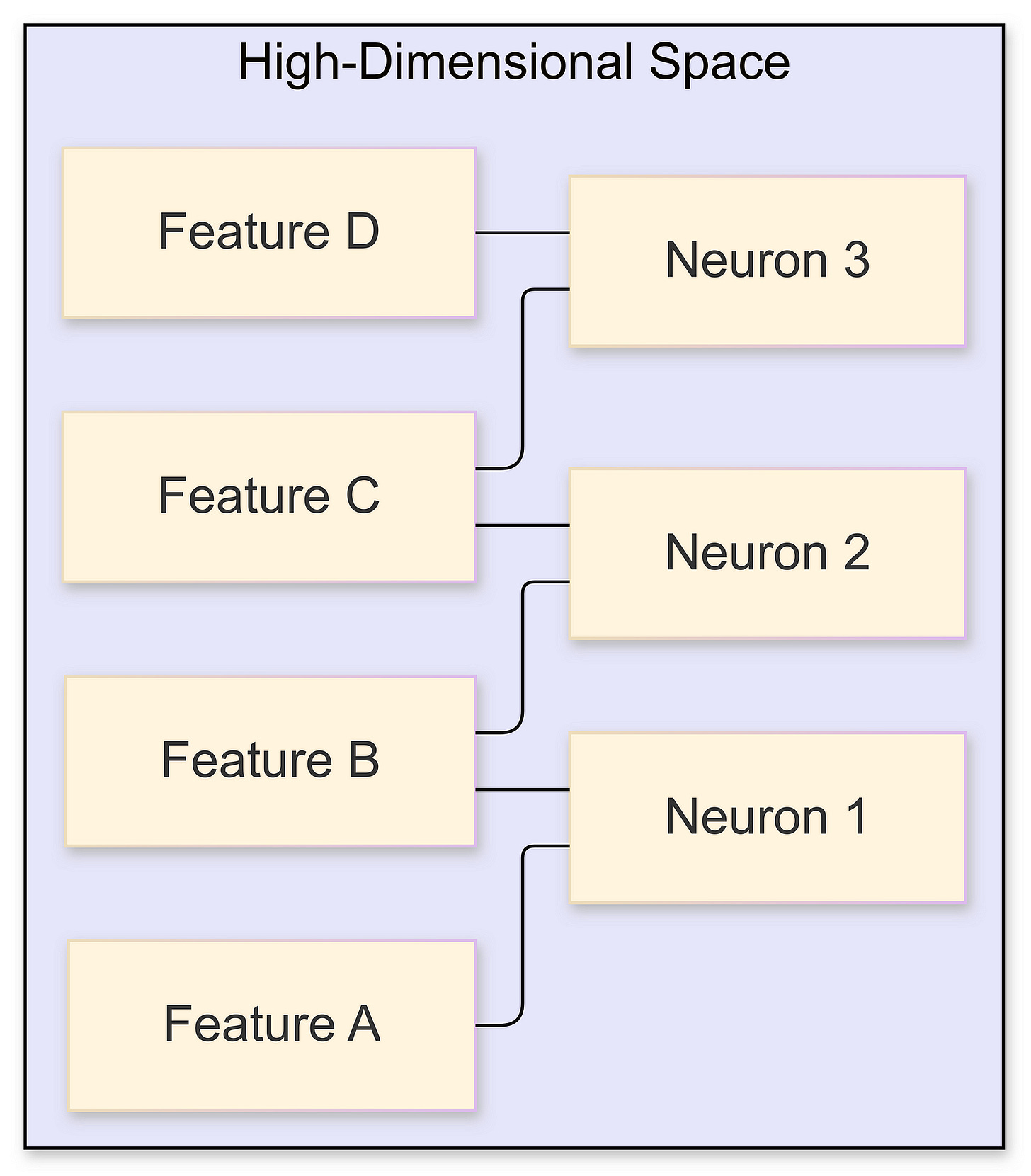

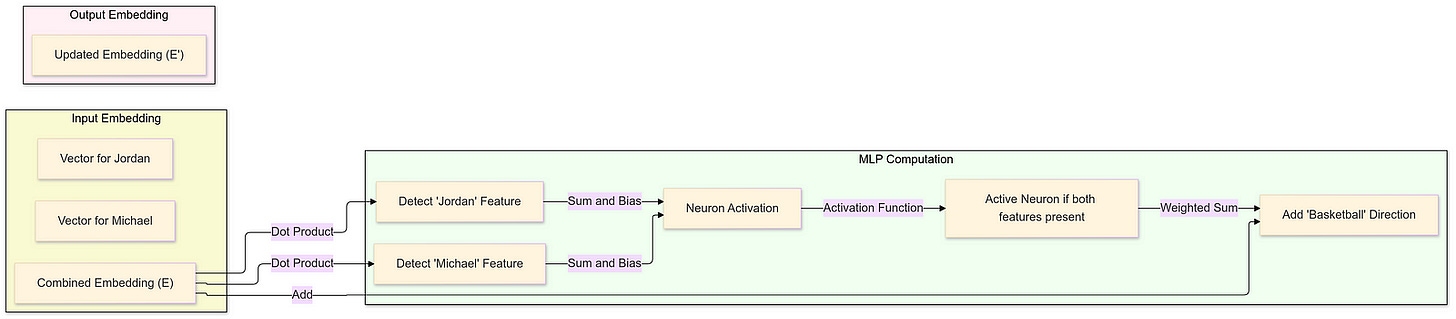

To illustrate how MLPs might store facts, consider a toy example where the model encodes the fact that “Michael Jordan plays basketball.” We start by assuming the existence of specific directions in the embedding space that represent the first name “Michael,” the last name “Jordan,” and the concept of “basketball.” When a vector encoding “Michael Jordan” flows through the MLP, these directional components interact in a way that allows the model to associate the name with the sport.

In this example, the MLP detects the presence of “Michael Jordan” by computing dot products with the specific directions for “Michael” and “Jordan.” The activation function ensures that only when both components are present does the neuron activate. The subsequent matrix multiplication adds the “basketball” direction to the embedding, effectively encoding the fact.

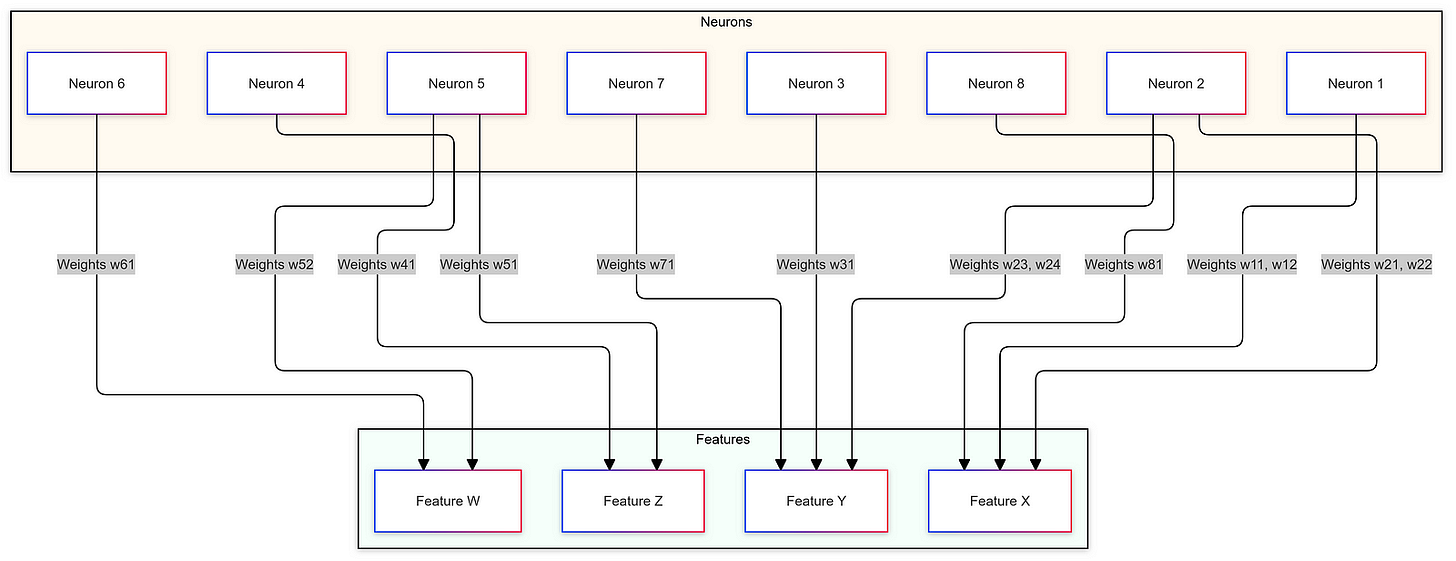

This toy example provides intuition into how MLPs might store factual information. However, in practice, the situation is far more complex. Due to the high dimensionality of the embedding space and the necessity to represent an enormous number of concepts, features are often stored in a superimposed manner. This leads us to the concept of superposition in neural networks, where multiple features are encoded within the same set of neurons by allowing them to overlap in the high-dimensional space.

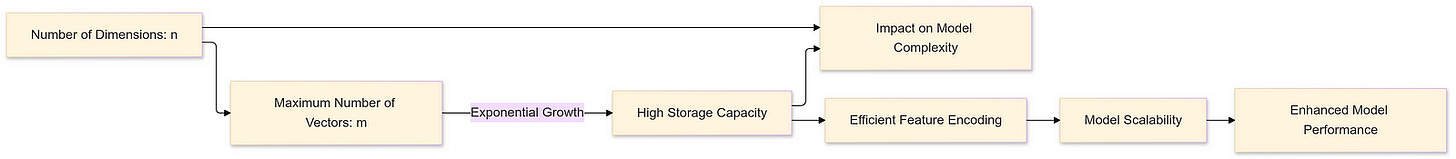

Superposition leverages the fact that in high-dimensional spaces, it’s possible to fit a vast number of approximately orthogonal directions. The Johnson-Lindenstrauss lemma supports this by indicating that the number of vectors you can cram into a space while maintaining near-perpendicular orientations grows exponentially with the number of dimensions. This property allows LLMs to store exponentially more features than the number of dimensions would suggest, enabling models like GPT-3 to handle an extensive range of ideas and facts.

The implications of superposition are significant. On one hand, it allows models to efficiently utilize their capacity, storing a vast amount of information without requiring an impractical number of parameters. On the other hand, it complicates interpretability. Individual neurons may no longer correspond to single, understandable features, making it challenging for researchers to dissect and understand the internal workings of the model. Techniques such as sparse autoencoders are employed in interpretability research to attempt to disentangle these superimposed features, though this remains an ongoing challenge.

To appreciate the scale of these operations, consider the parameter count in GPT-3. The multi-layer perceptrons alone account for approximately 116 billion parameters, constituting around two-thirds of the model’s total 175 billion parameters. This immense number of parameters underscores the model’s capacity to store and process vast amounts of information, with the majority dedicated to the MLPs that facilitate complex feature encoding and transformation.

Reflecting on whether the toy example accurately represents how facts are stored in real LLMs, it’s clear that while the example provides valuable intuition, the reality is far more intricate. The superimposed nature of feature encoding means that facts are not stored in isolated neurons but are instead distributed across complex, overlapping representations within the high-dimensional space. This distribution allows models to maintain efficiency and scalability but poses significant challenges for interpretability and understanding.

Understanding the storage of facts within LLMs has broader implications for model design, interpretability, and ethical considerations. As models become increasingly complex, ensuring transparency and mitigating biases becomes more challenging. The black-box nature of these models in critical applications underscores the importance of ongoing research aimed at making AI systems more transparent and understandable.